Abstract

Purpose

Studies that focus on the development of the typology of individual strength profiles are limited. Thus, this study aimed to determine strength profiles with different health outcomes based on the Three-Dimensional Inventory of Character Strengths (TICS).

Methods

The TICS was used to measure three-dimensional strengths: caring, inquisitiveness, and self-control. A total of 3536 community participants (1322 males and 2214 females with ages ranging from 17 to 50, M = 23.96, SD = 5.13) completed the TICS. A subsample (n = 853; female = 68.2%, male = 31.8%) was further required to complete the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale and Flourishing Scale. A latent profile analysis (LPA) was conducted in the total sample to identify the latent strength profiles. Then, a three-step method was implemented to compare the mental health outcomes between strength profiles in the subsample.

Results

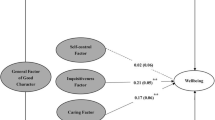

The LPA helped determine two subgroups based on the entire sample: the at-strengths group (high scores on all dimensions) and the at-risk group (low scores on all dimensions). As expected, the at-strengths group had less significant negative emotional symptoms (at-strengths group = 0.57, at-risk group = 0.83, χ2 = 33.54, p < .001) and had better psychological well-being (at-strengths group = 5.81, at-risk group = 4.64, χ2 = 276.64, p < .001).

Conclusions

This study identified two character strength profiles with different health outcomes. Specifically, populations with low-character strengths (caring, inquisitiveness, and self-control) were more likely to demonstrate poor mental health outcomes. Our findings also showed that a particular trait subtype can be considered in identifying high-risk populations and further implementing targeted strength-based interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603–619. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. New York: Oxford University Press.

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2015). Strengths-based positive psychology interventions: A randomized placebo-controlled online trial on long-term effects for a signature strengths- vs. a lesser strengths-intervention. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00456.

Proyer, R. T., Ruch, W., & Buschor, C. (2013). Testing strengths-based interventions: A preliminary study on the effectiveness of a program targeting curiosity, gratitude, hope, humor, and zest for enhancing life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(1), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9331-9.

Duan, W., Ho, S. M. Y., Tang, X., Li, T., & Zhang, Y. (2014). Character strength-based intervention to promote satisfaction with life in the Chinese University context. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(6), 1347–1361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9479-y.

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2014). Positive psychology interventions in people aged 50–79 years: Long-term effects of placebo-controlled online interventions on well-being and depression. Aging & Mental Health, 18(8), 997–1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.899978.

Mongrain, M., & Anselmo-Matthews, T. (2012). Do positive psychology exercises work? A replication of Seligman et al. (2005). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 382–389. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21839.

Conrod, P. J., Castellanos, N., & Mackie, C. (2008). Personality-targeted interventions delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 49(2), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01826.x.

Mahu, I. T., Doucet, C., O’Leary-Barrett, M., & Conrod, P. J. (2015). Can cannabis use be prevented by targeting personality risk in schools? Twenty-four-month outcome of the adventure trial on cannabis use: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 110(10), 1625–1633. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12991.

Strickhouser, J. E., Zell, E., & Krizan, Z. (2017). Does personality predict health and well-being? A metasynthesis. Health Psychology, 36(8), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000475. doi.

Jokela, M., Pulkki-Råback, L., Elovainio, M., & Kivimäki, M. (2014). Personality traits as risk factors for stroke and coronary heart disease mortality: Pooled analysis of three cohort studies. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(5), 881–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-013-9548-z.

Osborne, D., & Sibley, C. G. (2013). After the disaster: Using the big-five to predict changes in mental health among survivors of the 2011 Christchurch earthquake. Disaster Prevention and Management, 22(5), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-09-2013-0161.

Haridas, S., Bhullar, N., & Dunstan, D. A. (2017). What’s in character strengths? Profiling strengths of the heart and mind in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 113, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.006.

Peterson, C. (2007). Brief strengths test. Cincinnati: VIA Institute.

Bird, V. J., Le, B. C., Leamy, M., Larsen, J., Oades, L. G., Williams, J., et al. (2012). Assessing the strengths of mental health consumers: A systematic review. Psychological Assessment, 24(4), 1024–1033. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028983.

Ho, S. M. Y., Rochelle, T. L., Law, L. S. C., Duan, W., Bai, Y., & Shih, S. M. (2014). Methodological issues in positive psychology research with diverse populations: Exploring strengths among Chinese adults. Netherlands: Springer.

Mcgrath, R. E. (2014). Integrating psychological and cultural perspectives on virtue: The hierarchical structure of character strengths. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(5), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.994222.

Kristjánsson, K. (2010). Positive psychology, happiness, and virtue: The troublesome conceptual issues. Review of General Psychology, 14(4), 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020781.

Cheung, F. M., Van, dV., Fons, J. R., & Leong, F. T. L. (2011). Toward a new approach to the study of personality in culture. American Psychologist, 66(7), 593–603. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022389.

Duan, W., & Bu, H. (2017). Development and initial validation of a short three-dimensional inventory of character strengths. Quality of Life Research, 26(9), 2519–2531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1579-4.

Duan, W., & Ho, S. M. Y. (2016). Three-dimensional model of strengths: Examination of invariance across gender, age, education levels, and marriage status. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(2), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-0038-y.

Duan, W., Ho, S. M. Y., Yu, B., Tang, X., Zhang, Y., Li, T., et al. (2012). Factor structure of the Chinese virtues questionnaire. Research on Social Work Practice, 22(6), 680–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731512450074.

Duan, W., & Ho, S. M. Y. (2017). Three-dimensional model of strengths: Examination of invariance across gender, age, education levels, and marriage status. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(2), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-0038-y.

Dziak, J. J., Bray, B. C., Zhang, J., Zhang, M., & Lanza, S. T. (2016). Comparing the performance of improved classify-analyze approaches for distal outcomes in latent profile analysis. Methodology European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral & Social Sciences, 12(4), 107. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000114.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2015). Chris Peterson’s unfinished masterwork: The real mental illnesses. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.888582.

Li, T., Duan, W., & Guo, P. (2017). Character strengths, social anxiety, and physiological stress reactivity. PeerJ. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3396.

Rassart, J., Luyckx, K., Goossens, E., Oris, L., Apers, S., & Moons, P. (2016). A big five personality typology in adolescents with congenital heart disease: Prospective associations with psychosocial functioning and perceived health. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9547-x.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety and stress scales (2nd ed.). Sydney: Psychological Foundation.

Wang, K., Shi, H. S., Geng, F. L., Zou, L. Q., Tan, S. P., Wang, Y., et al. (2016). Cross-cultural validation of the depression anxiety stress scale–21 in China. Psychological Assessment, 28(5), e88. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000207.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Chu, K. P., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y.

Tang, X., Duan, W., Wang, Z., & Liu, T. (2016). Psychometric evaluation of the simplified Chinese version of flourishing scale. Research on Social Work Practice, 26(5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731514557832.

Bakk, Z., & Vermunt, J. K. (2016). Robustness of stepwise latent class modeling with continuous distal outcomes. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.955104.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915181.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (2012). Mplus user’s guide (version 7.2). Los Angeles: Muthén &Muthén.

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396.

Liu, X., Lv, Y., Ma, Q., Guo, F., Yan, X., & Ji, L. (2016). The basic features and patterns of character strengths among children and adolescents in China. Studies of Psychology & Behavior, 27(5), 536–542. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.

Niemiec, R. M. (2013). VIA character strengths: Research and practice (the first 10 years). In H. H. Knoop, A. Delle & Fave (Eds.), Well-being and cultures: Perspectives from positive psychology (pp. 11–29). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Hausler, M., Strecker, C., Huber, A., Brenner, M., Höge, T., & Höfer, S. (2017). Distinguishing relational aspects of character strengths with subjective and psychological well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01159.

Duan, W. (2016). The benefits of personal strengths in mental health of stressed students: A longitudinal investigation. Quality of Life Research, 25(11), 2879–2888. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1320-8.

Ruch, W., Huber, A., Beermann, U., & Proyer, R. T. (2007). Character strengths as predictors of the “good life” in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Studii Şi Cercetari din domeniul ştiinţelor socio-umane, 16, 123–131. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-3648.

Freidlin, P., Littman-Ovadia, H., & Niemiec, R. M. (2017). Positive psychopathology: Social anxiety via character strengths underuse and overuse. Personality & Individual Differences, 108(C), 50–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.003.

Toner, E., Haslam, N., Robinson, J., & Williams, P. (2012). Character strengths and wellbeing in adolescence: Structure and correlates of the values in action inventory of strengths for children. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(5), 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.014.

Gillham, J., AdamsDeutsch, Z., Werner, J., Reivich, K., CoulterHeindl, V., Linkins, M., et al. (2011). Character strengths predict subjective well-being during adolescence. Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.536773.

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2013). What good are character strengths beyond subjective well-being? The contribution of the good character on self-reported health-oriented behavior, physical fitness, and the subjective health status. Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(3), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.777767.

Ho, S. M. Y., Li, W. L., Duan, W., Siu, B. P. Y., Yau, S., Yeung, G., et al. (2016). A brief strengths scale for individuals with mental health issues. Psychological Assessment, 28(2), 147. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000164.

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998) What good are positive emotions?. Review of General Psychology, 2, 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300.

Reynolds, F. (2000). Managing depression through needlecraft creative activities: A qualitative study. Arts in Psychotherapy, 27(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-4556(99)00033-7.

Chan, M. (2013). Mobile phones and the good life: Examining the relationships among mobile use, social capital and subjective well-being. New Media & Society, 17(1), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813516836.

Martin, L. R., Friedman, H. S., & Schwartz, J. E. (2007). Personality and mortality risk across the life span: The importance of conscientiousness as a biopsychosocial attribute. Health Psychology, 26(4), 428. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.428.

Deary, I. J., Weiss, A., & Batty, G. D. (2010). Intelligence and personality as predictors of illness and death: How researchers in differential psychology and chronic disease epidemiology are collaborating to understand and address health inequalities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 11(2), 53–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/41038735.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801.

Furnham, A., Treglown, L., Hyde, G., & Trickey, G. (2016). The bright and dark side of altruism: Demographic, personality traits, and disorders associated with altruism. Journal of Business Ethics, 134(3), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2435-x.

Moran, C. M., Diefendorff, J. M., Kim, T. Y., & Liu, Z. Q. (2012). A profile approach to self-determination theory motivations at work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(3), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.09.002.

Duan, W., & Xie, D. (2016). Measuring adolescent flourishing: Psychometric properties of flourishing scale in a sample of Chinese adolescents. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282916655504.

Zhou, Y., & Liu, X. P. (2011). Character strengths of college students: The relationship between character strengths and subjective well-being. Psychological Development & Education, 27(5), 536–542. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2011.05.005.

Acknowledgements

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: National Social Science Foundation—Youth Project (17CSH073) and Wuhan University Humanities and Social Sciences Academic Development Program for Young Scholars (WHU2016019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors, Wenjie Duan and Yuhang Wang, declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Human Subjects Ethics Sub-Committee of the Department of Sociology and Wuhan University approved this study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained by click a button from the participants before they completed the survey.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, W., Wang, Y. Latent profile analysis of the three-dimensional model of character strengths to distinguish at-strengths and at-risk populations. Qual Life Res 27, 2983–2990 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1933-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1933-1