Abstract

Purpose

Perceived social support is known to be an important predictor of health outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). This study investigates patterns of longitudinal trajectories of patient-reported perceived social support in individuals with ACS.

Methods

Data are from 3013 patients from the Alberta Provincial Project for Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease registry who had their first cardiac catheterization between 2004 and 2011. Perceived social support was assessed using the 19-item Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS) 2 weeks, 1 year, and 3 years post catheterization. Group-based trajectory analysis based on longitudinal multiple imputation model was used to identify distinct subgroups of trajectories of perceived social support over a 3-year follow-up period.

Results

Three distinct social support trajectory subgroups were identified, namely: “High” social support group (60%), “Intermediate” social support group (30%), and “Low” social support subgroup (10%). Being female (OR = 1.67; 95% CI = [1.18–2.36]), depression (OR = 8.10; 95% CI = [4.27–15.36]) and smoking (OR = 1.70; 95% CI = [1.23–2.35]) were predictors of the differences among these trajectory subgroups.

Conclusion

Although the majority of ACS patients showed increased or fairly stable trajectories of social support, about 10% of the cohort reported declining social support. These findings can inform targeted psycho-social interventions to improve their perceived social support and health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Strike, P. C., & Steptoe, A. (2005). Behavioral and emotional triggers of acute coronary syndromes: A systematic review and critique. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67(2), 179–186.

Chung, M. C., Berger, Z., & Rudd, H. (2008). Coping with posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbidity after myocardial infarction. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(1), 55–64.

Kumar, A., & Cannon, C. P. (2009). Acute coronary syndromes: Diagnosis and management, part I. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 84(10), 917–938, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60509-0.

Graven, L. J., & Grant, J. S. (2014). Social support and self-care behaviors in individuals with heart failure: An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(2), 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.06.013.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social Relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLOS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

Dekker, R. L., Peden, A. R., Lennie, T. A., Schooler, M. P., & Moser, D. K. (2009). Living with depressive symptoms: Patients with heart failure. American journal of critical care: An Official Publication. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 18(4), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2009672.

Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S., & Hanratty, B. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102(13), 1009–1016. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790.

Hakulinen, C., Pulkki-Raback, L., Virtanen, M., Jokela, M., Kivimaki, M., & Elovainio, M. (2018). Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for myocardial infarction, stroke and mortality: UK Biobank cohort study of 479 054 men and women. Heart, 104(18), 1536–1542. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312663.

White, A. M., Philogene, G. S., Fine, L., & Sinha, S. (2009). Social support and self-reported health status of older adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 99(10), 1872–1878. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.146894.

Simms, A. D., Batin, P. D., Kurian, J., Durham, N., & Gale, C. P. (2012). Acute coronary syndromes: An old age problem. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology: JGC, 9(2), 192–196. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1263.2012.01312.

Holden, L., Lee, C., Hockey, R., Ware, R. S., & Dobson, A. J. (2015). Longitudinal analysis of relationships between social support and general health in an Australian population cohort of young women. Quality of Life Research, 24(2), 485–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0774-9.

Lett, H. S., Blumenthal, J. A., Babyak, M. A., Strauman, T. J., Robins, C., & Sherwood, A. (2005). Social support and coronary heart disease: Epidemiologic evidence and implications for treatment. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67(6), 869–878.

Bosworth, H. B., Siegler, I. C., Olsen, M. K., Brummett, B. H., Barefoot, J. C., Williams, R. B., et al. (2000). Social support and quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 9(7), 829–839.

Norris, C. M., Spertus, J. A., Jensen, L., Johnson, J., Hegadoren, K. M., Ghali, W. A., et al. (2008). Sex and gender discrepancies in health-related quality of life outcomes among patients with established coronary artery disease. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 1(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.793448

Staniute, M., Brozaitiene, J., & Bunevicius, R. (2013). Effects of social support and stressful life events on health-related quality of life in coronary artery disease patients. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 28(1), 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0b013e318233e69d

Leifheit-Limson, E. C., Reid, K. J., Kasl, S. V., Lin, H., Jones, P. G., Buchanan, D. M., et al. (2010). The role of social support in health status and depressive symptoms after acute myocardial infarction: Evidence for a stronger relationship among women. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 3(2), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.899815.

Ghali, W. A., Knudtson, M. L., & on behalf of the APPROACH Investigators. (2000). Overview of the alberta provincial project for outcome assessment in coronary heart disease. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 16(10), 1225–1230.

Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 32(6), 705–714.

Gjesfjeld, C. D., Greeno, C. G., & Kim, K. H. (2008). A confirmatory factor analysis of an abbreviated social support instrument: The MOS-SSS. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(3), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507309830.

Robitaille, A., Orpana, H., & McIntosh, C. N. (2011). Psychometric properties, factorial structure, and measurement invariance of the English and French versions of the Medical Outcomes Study social support scale. Health Reports, 22(2), 33–40.

Stafford, L., Berk, M., & Jackson, H. J. (2007). Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with coronary artery disease. General Hospital Psychiatry, 29(5), 417–424.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370.

Stern, A. F. (2014). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occupational Medicine (Oxford, England), 64(5), 393–394. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqu024.

Harel, O., Mitchell, E. M., Perkins, N. J., Cole, S. R., Tchetgen Tchetgen, E. J., Sun, B., et al. (2018). Multiple imputation for incomplete data in epidemiologic studies. American Journal of Epidemiology, 187(3), 576–584. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx349.

Ma, J., Raina, P., Beyene, J., & Thabane, L. (2012). Comparing the performance of different multiple imputation strategies for missing binary outcomes in cluster randomized trials: A simulation study. Journal of Open Access Medical Statistics, 2, 93–103.

Faris, P. D., Ghali, W. A., Brant, R., Norris, C. M., Galbraith, P. D., Knudtson, M. L., et al. (2002). Multiple imputation versus data enhancement for dealing with missing data in observational health care outcome analyses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 55(2), 184–191.

Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (2002). Statistical Analysis with Missing Data (2nd ed.). New Yorkk: Wiley.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modelling of development. London: Harvard University Press.

Jones, B. L., Nagin, D. S., & Roeder, K. (2001). A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating development trajectories. Sociological Methods & Research, 29(3), 374–393.

Nagin, D. S., & Odgers, C. L. (2010). Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 109–138. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413.

Nagin, D. S. (2014). Group-based trajectory modeling: An overview. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism, 65(2–3), 205–210. https://doi.org/10.1159/000360229.

Andruff, H., Carraro, N., Thompson, A., & Gaudreau, P. (2009). Latent class growth modelling: A tutorial. Tutorials Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 5, 11–24.

Schafer, J. L. (1997). Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. New York: Chapman & Hall.

SAS Institute Inc. (2013). Base SAS® 9.4 procedures guide: Statistical procedures. Cary: SAS Institute Inc.

Powers, S. M., Bisconti, T. L., & Bergeman, C. S. (2014). Trajectories of social support and well-being across the first two years of widowhood. Death Studies, 38(8), 499–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2013.846436.

Dean, A., Matt, G. E., & Wood, P. (1992). The effects of widowhood on social support from significant others. Journal of Community Psychology, 20(4), 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(199210)20:43.0.CO;2-V.

Shankar, A., Mcmunn, A., Banks, J., & Steptoe, A. (2011). Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychology, 30(4), 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022826.

Kristofferzon, M. L., Lofmark, R., & Carlsson, M. (2003). Myocardial infarction: Gender differences in coping and social support. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 44(4), 360–374.

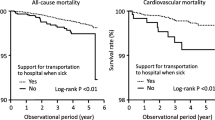

Ikeda, A., Iso, H., Kawachi, I., Yamagishi, K., Inoue, M., & Tsugane, S. (2008). Social support and stroke and coronary heart disease. Stroke, 39(3), 768–775. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.496695.

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., Schroevers, M. J., Aarnink, J., van der Heijden, D. J., van Es, S. M., et al. (2009). Cognitive coping and goal adjustment after first-time myocardial infarction: Relationships with symptoms of depression. Behavioral Medicine (Washington, D. C.), 35(3), 79–86, https://doi.org/10.1080/08964280903232068.

Son, H., Friedmann, E., Thomas, S. A., & Son, Y. J. (2016). Biopsychosocial predictors of coping strategies of patients postmyocardial infarction. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 22(5), 493–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12465.

Helgeson, V. S. (2003). Social support and quality of life. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 12(Suppl 1), 25–31.

McConnell, T. R., Trevino, K. M., & Klinger, T. A. (2011). Demographic differences in religious coping after a first-time cardiac event. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, 31(5), 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0b013e31821c41f0.

Funding

This research was supported by the University of Calgary O’Brien Institute of Public Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there’s no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (REB14-1320).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7 and Fig. 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, M., Norris, C.M., Graham, M.M. et al. Trajectories of perceived social support in acute coronary syndrome. Qual Life Res 28, 1365–1376 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-02095-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-02095-4