Abstract

Purpose

This prospective study aimed to identify the different trajectories of quality of life (QOL) in patients with distal radius fractures (DRF) and ankle fractures (AF). Secondly, it was examined if subgroups could be characterized by sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological variables.

Methods

Patients (n = 543) completed the World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment instrument-Bref (WHOQOL-Bref), the pain, coping, and cognitions questionnaire, NEO-five factor inventory (neuroticism and extraversion), and the state-trait anxiety inventory (short version) a few days after fracture (i.e., pre-injury QOL reported). The WHOQOL-Bref was also completed at three, six, and 12 months post-fracture. Latent class trajectory analysis (i.e., regression model) including the Step 3 method was performed in Latent Gold 5.0.

Results

The number of classes ranged from three to five for the WHOQOL-Bref facet and the four domains with a total variance explained ranging from 71.6 to 79.4%. Sex was only significant for physical and psychological QOL (p < 0.05), whereas age showed significance for overall, physical, psychological, and environmental QOL (p < 0.05). Type of treatment or fracture type was not significant (p > 0.05). Percentages of chronic comorbidities were 1.8 (i.e., social QOL) to 4.5 (i.e., physical QOL) higher in the lowest compared to the highest QOL classes. Trait anxiety, neuroticism, extraversion, pain catastrophizing, and internal pain locus of control were significantly different between QOL trajectories (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

The importance of a biopsychosocial model in trauma care was confirmed. The different courses of QOL after fracture were defined by several sociodemographic and clinical variables as well as psychological characteristics. Based on the identified characteristics, patients at risk for lower QOL may be recognized earlier by health care providers offering opportunities for monitoring and intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Trauma leading to fractures of the distal radius (DRF) or ankle (AF) is quite common, with incidence rates of 26–32 per 104 person years for DRF [1,2,3] and 10.1 per 104 person years regarding AF [4]. Patients may experience secondary fracture displacement [5,6,7], suffer from pain, stiffness, sleep difficulties, reduced grip strength, and/or restricted range of motion [8,9,10,11,12], which affect employment [13,14,15], sports [8, 9], and quality of life (QOL; i.e., patients’ subjective evaluations of their functioning and well-being [16,17,18]).

The course of QOL post-fracture may be influenced by sociodemographic, clinical, and psychosocial variables. Some sociodemographic and clinical predictors of health status (HS) [19] and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [20], constructs related to QOL, have been studied in patients with DRF or AF. However, results were inconclusive with regard to age, sex, educational level, marital status, arthritis, type of treatment, type of fracture, and certain radiographic indices [21, 22]. Moreover, personality and patients’ health beliefs have not been examined in relation to QOL in patients with DRF or AF, although personality traits have shown to be valuable predictors in areas as chronic pain in orthopedics and in oncology research [23,24,25,26]. Pain catastrophizing which includes negative pain-related cognitions like rumination, helplessness, and magnification [27] was a significant predictor of HS/HRQOL five to eight months after musculoskeletal trauma [28, 29]. In patients after whiplash injury, the early use of passive pain coping strategies was related to slower recovery [30] and in oncological studies a high level of avoidance coping was associated with impaired HRQOL [31] suggesting the importance of psychological characteristics. Furthermore, health locus of control (HLOC) beliefs, the belief to be either in charge of yourself regarding your health (i.e., internal HLOC) or the externalization of this control to powerful others such as physicians or fate [32, 33], may also be interesting to take into consideration in relation to QOL in patients with fractures. In elderly women with hip fractures, high levels of internal HLOC predicted higher levels of daily living activities [34]. In our study, we will focus on a specific facet of HLOC i.e., pain locus of control (PLOC) [33], which is assumed to be particularly relevant in patients with fractures.

Better insight in the factors that may influence the course of QOL after fracture facilitates the identification of patients that need additional monitoring or care in clinical practice. Moreover, it may offer directions for the development of psychological interventions to improve patients’ QOL. Therefore, in this study, we identified QOL trajectories of patients with DRF or AF up to 12 months post-fracture (i.e., using latent class trajectory analysis) and examined if subgroups could be characterized by sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological variables.

Methods

Patients

Patients were invited to participate in this study with inclusion starting January 2012 at the St. Elisabeth Hospital and September 2012 at the TweeSteden Hospital, Tilburg, The Netherlands (i.e., two locations of the same hospital). Analyses were performed on data from patients included up to November 2014. The main inclusion criteria were the diagnosis of an isolated unilateral DRF or AF which was inflicted by trauma (i.e., no stress fractures) and a minimal age of 18 years old. The diagnosis had to be confirmed by X-ray. Patients with multiple trauma were not included (i.e., additional injuries besides the DRF or AF caused by the traumatic event). Because of the focus on self-report measures in this study, patients were excluded when they were not able to complete the questionnaires themselves (e.g., insufficient knowledge of the Dutch language). The presence of severe psychopathology (e.g., suicidal) or severe physical comorbidity (e.g., lung cancer) were exclusion criteria as well.

Design

Eligible patients were invited to participate in the study within a few days after their visit to the Emergency Department (i.e., during this visit fracture diagnosis was established) by a member of the research team. Patients provided informed consent before entering the study. Patients were asked to complete self-report measures at the time of diagnosis (Time-0retrospective), 3 months post-fracture (Time-1), 6 months post-fracture (Time-2), and 12 months post-fracture (Time-3). The measurement at Time-0retrospective consisted in general of a retrospectively reported pre-injury status by the patient to establish a baseline. Personality, pain beliefs, and pain coping were assessed without pre-injury instruction at baseline. Personality traits are assumed to be stable characteristics over time in a variety of situations. In addition, pain beliefs and coping were answered a few days post-fracture because pain levels were expected to be at their highest levels around that time point. Patients received the self-report measures as paper questionnaire booklets at their home addresses. The local Medical Ethics Committee approved the study.

Fracture classification

DRF and AF were independently classified by a trauma surgeon/senior trauma resident according to the Müller AO classification of long bones [35] based on the primary X-ray. Initial agreement was 61.9%. Consensus meetings were scheduled in which disagreements were discussed.

Measures

Age, sex, marital status, educational level, employment status, smoking, chronic comorbidities, type of injury, and type of treatment were collected by a general questionnaire added to the booklet of Time-0retrospective.

The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment instrument-Bref (WHOQOL-Bref) is a 26-item QOL questionnaire encompassing four domains: Physical health, Psychological health, Social relationships, and Environment [36]. Moreover, two items form the facet overall QOL and general health. Items are rated on five-point Likert scales with higher scores indicating better QOL. Psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-Bref are satisfactory in patients with different diseases [37,38,39,40,41].

Pain beliefs and coping were assessed with the 42-item Pain, Coping, and Cognition Questionnaire (PCCL) [33, 42]. The PCCL encompasses four subscales: Catastrophizing, Pain coping, Internal locus of control, and External locus of control. Items of the PCCL are rated on a six-point Likert format. A higher score indicates more catastrophizing, higher variability of pain coping strategies, or a higher internal/external locus of control. The psychometrics of the PCCL was examined in chronic pain patients and was adequate to good [33].

The NEO-five factor inventory (NEO-FFI) is a frequently used personality questionnaire that measures the five personality traits of the Five Factor Model [43,44,45]: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, and Openness to experience. For this study, only the subscales Neuroticism (12 items) and Extraversion (12 items) were completed. Items are responded on five-point Likert scales. Higher scores indicate higher levels of neuroticism or extraversion. The psychometric properties of the NEO-FFI appeared to be sufficient [44].

Trait anxiety was measured by the Trait anxiety subscale (10 items) [46] adapted from the state-trait anxiety inventory [47,48,49]. Items are answered on four-point Likert scales. Higher scores represent a stronger tendency to experience anxiety across different situations. The 10-item trait scale is a reliable and valid measure [46].

Statistical analyses

Participants were compared with non-participants performing Chi square tests (i.e., sex, type of fracture, AO classification) and an independent samples t test (i.e., age).

Latent class trajectory analysis was performed to determine the number of non-observed classes in the course of QOL using the latent class regression model in Latent GOLD 5.0 [50,51,52]. Analyses were performed repeatedly for the five dependent variables: Physical health, Psychological health, Social relationships, Environment, and the facet Overall QOL and general health of the WHOQOL-Bref. In case of strong non-normality and less than 20 unique scores in a dependent variable, this variable was analyzed as an ordinal variable in which scores were merged in maximal 10 bins of approximately equal size (i.e., minimal 10% of the cases [52]).

The factor ‘time’ was used in the models as a nominal variable with four time points. No covariates were included in the models. Subsequently, models with one to eight classes were estimated. The optimum number of classes was based on the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), which is an indicator of model fit taking complexity of the model into account as well. The model with the number of classes with the lowest BIC was selected. Each patient was assigned a class membership probability for each class. The labeling of the classes is based on the level of each group within the model. The Wald(0) test of the predictor time is a global test indicating if any effect of time is present (i.e., if there is a significant deviation from zero). In addition, the Wald(=) test indicates if this effect of time significantly differs between classes.

The Step 3 method was used to take uncertainty in the prediction of class membership into account to prevent bias [51]. Patients in the different classes (i.e., with consequently a different trajectory of QOL) were compared on sociodemographic (i.e., age, sex, marital status, educational level, employment status), clinical (i.e., smoking, chronic comorbidities, type of fracture, AO classification, type of treatment), and psychological characteristics (i.e., personality traits, coping cognitions, and strategies) using the Step 3 method (i.e., Analysis Dependent). The corrected p values of the Wald(0) test using the Step 3 method were presented. A 0.05 level of significance was applied to evaluate statistical significance. To facilitate the interpretability of the outcomes, the number and percentage or the mean and standard deviation were shown in the tables where the class membership was based on the highest class probability. The different trajectories were presented as line figures based on the estimated marginal means (continuous dependent variables) and the class means (ordinal dependent variables).

Results

In total, 543 patients returned at least one of the questionnaire sets at a given time point. The participation rate was 47.0%. Compared to non-participants, participants were older (i.e., respectively 50.4 versus 57.0 years of age; p < 0.001). In addition, participants were more likely to be women (72.4% was female), while 60.5% of the non-participants was female (p < 0.001). No differences were found on fracture type (i.e., DRF versus AF) and AO classification (i.e., 23/44A versus 23/44B versus 23/44C) between participants versus non-participants (p > 0.05). The characteristics of the total sample are shown in Table 1.

Trajectories of QOL

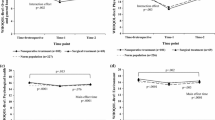

Social relationships and Overall QOL and general health were transformed to ordinal variables. The number of classes ranged from three to five (Table 2). The total variance explained by the models ranged from 71.6 to 79.4%. The effects of time were present in all models. The time effect was significantly different between the classes (Fig. 1b–e), except for Overall QOL and general health (Wald(=) p = 0.87, Fig. 1a). Table 3 shows the optimum number of classes based on the lowest BIC values for all QOL models.

a WHOQOL-Bref Overall QOL and general health. Abbreviations Time-0retrospective = pre-injury status, Time-1 = 3 months post-fracture, Time-2 = six months post-fracture, Time-3 = 12 months post-fracture, QOL = quality of life, WHOQOL-Bref = World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment instrument-Bref. Notes Class means are shown. A higher score indicates a better quality of life. Percentages are shown of the sample included in each class. b WHOQOL-Bref Physical health. Notes Estimated marginal means are shown. A higher score indicates a better quality of life. Percentages are shown of the sample included in each class. c WHOQOL-Bref Psychological health. Notes Estimated marginal means are shown. A higher score indicates a better quality of life. Percentages are shown of the sample included in each class. d WHOQOL-Bref Social relationships. Notes Class means are shown. A higher score indicates a better quality of life. Percentages are shown of the sample included in each class. e WHOQOL-Bref Environment. Notes Estimated marginal means are shown. A higher score indicates a better quality of life. Percentages are shown of the sample included in each class

Overall QOL and general health included three classes: Poor, Moderate, and Good (Table 4). Sociodemographic factors were significant, except for sex. Patients in the Poor QOL class had the highest age, were less frequently partnered, and had the lowest employment rate. In the Good QOL class, patients were 1.6 times more often highly educated compared to the Poor QOL class. Classes differed significantly on smoking and the presence of chronic comorbidities. The proportion of patients being non-smokers and patients without chronic comorbidities increased per class in ascending magnitude of QOL. All psychological variables reached significance, expect for pain coping. Patients in the Good QOL class had higher mean scores on extraversion and internal PLOC, and lower scores for neuroticism and trait anxiety in this class, compared to the other two classes.

The four trajectories of Physical health contained a Poor, Moderate, Good, and Excellent class (Table 4). Significant differences were found on all examined sociodemographic and clinical variables, except chronic comorbidities. Patients in the Good and Excellent QOL class were younger than the patients in the Poor and Moderate QOL class. Female contribution was lowest in the Good and Excellent QOL classes, but still up to 65.7%. Moreover, in the Poor and Moderate QOL class, up to 68.7% had a partner compared to 81.0–83.1% of the patients in the Good and Excellent QOL classes. In the Excellent QOL group, patients had almost twice as often a high educational level and employed compared to the Poor QOL group. Patients in the Poor QOL group had more than fourth as often chronic comorbidities compared to patients in the Excellent QOL group. Classes differed significantly on all the psychological characteristics, except pain coping. Patients in the four different classes, in ascending magnitude of QOL, had lower scores on trait anxiety, neuroticism, and pain catastrophizing, and higher scores on extraversion. Patients in the Good and Excellent QOL class had higher scores on internal PLOC and lower scores on external PLOC compared to the other two classes.

The five trajectories of Psychological health included a Poor, Moderate, Adequate, Good, and Excellent class (Table 5). All sociodemographic variables reached significance. Patients in the Moderate QOL class were the oldest. In the Good and Excellent QOL group, the proportion male and partnered patients were higher than in the classes with lower QOL. More than half of the patients in the Adequate, Good, and Excellent QOL class had a high educational level and were more often employed. The proportion of patients reporting chronic comorbidities was lower for those classes representing higher QOL. Pain coping and external PLOC were not significant. Lower scores on trait anxiety, neuroticism, and pain catastrophizing, as well as higher scores on extraversion and internal PLOC were found for those trajectories representing higher QOL in ascending order.

The three classes of Social relationships contained a Poor, Moderate, and Good class (Table 6). Only two out of five sociodemographic variables were significant: marital status and employment. In the Poor QOL class the proportion of having a partner was lowest. The proportion of patients being employed increased per class in ascending magnitude of QOL. Smoking and chronic comorbidities reached significance. Almost twice as often patients smoked in the Poor QOL class and had chronic comorbidities compared to the Good QOL class. The psychological variables were all significant, except for pain coping and external PLOC. The lowest scores for trait anxiety and neuroticism, and the highest scores on extraversion were detected for the good QOL class. Patients with the strongest tendency to catastrophize regarding pain and using the least internal PLOC were found in the Poor QOL class.

The four trajectories of Environment encompassed a Poor, Moderate, Good, and Excellent class (Table 6). Classes differed significantly on all sociodemographic variables, except for sex. Patients in the Poor and Excellent QOL classes were older compared with the Moderate and Good QOL classes. In the Poor and Moderate QOL class, up to 73.9% had a partner whereas in the Good and Excellent QOL at least 80.2% reported having a partner. The proportion of patients with high educational level was the highest in the classes Good and Excellent QOL. Additionally, in the classes Good and Moderate QOL patients had most often a job. The proportion of non-smokers and patients without chronic comorbidities increased per class in ascending magnitude of QOL. Trends showed that lower scores on trait anxiety, neuroticism, pain catastrophizing, and external PLOC were observed in the classes in ascending magnitude of QOL. The highest mean scores for extraversion and internal PLOC were found for the Good and Excellent QOL class compared to the other classes.

Discussion

This was the first study using latent class trajectory analyses to identify QOL trajectories (i.e., classes) in patients with a DRF or AF up to 12 months after fracture. In addition, we explored if these patient groups differed on sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological variables (i.e., biopsychosocial approach). The acquired knowledge can facilitate the identification of patients that might need additional monitoring or care.

Subgroups were characterized by several sociodemographic variables of which clinicians are advised to take notice of when treating patients with AF or DRF: i.e., age, sex, marital status, educational level, and employment status. Prior research on AF and DRF in relation to HS and HRQOL reported mainly inconsistent findings on the role of sociodemographic variables [21, 22]. Generally, we found that patients in the lower QOL trajectories (i.e., overall, physical, and environmental) were older. The proportion of women was higher in the lower physical and psychological QOL trajectories. Two studies in AF and DRF are mainly in agreement with these results suggesting that women are at risk for lower HS after fracture [53, 54]. In addition, patients in the higher QOL trajectories more frequently had a partner, showing protective value of the presence of a significant other. Furthermore, a higher educational level (i.e., except for social QOL) and higher job participation were found in the trajectories representing higher QOL. The positive association of educational level with QOL was also reflected in two studies on DRF and AF that reported lower physical HS in patients with lower formal education [55, 56].

Previous research was inconclusive on the role of clinical variables [21, 22] but our study suggests an important distinction between injury-specific and general clinical variables. The QOL trajectories showed no significant differences on injury-specific variables: fracture diagnosis (DRF versus AF), type of treatment (operative versus non-operative treatment), and AO classification. The finding that diagnosis was not significant could be explained by the use of the WHOQOL-BREF, a generic QOL instrument. This instrument is completed by the patient (subjective), but also contains items about the level of satisfaction (e.g., ‘How much do you enjoy life?’) and to what extent a patient is bothered (subjective), instead of items (e.g., ‘Are you able to walk the stairs) that could be considered objective items, because they could be completed by someone else by observing the patient’s functioning. Only general clinical variables (i.e., chronic comorbidities and smoking) were significantly related to class membership. Percentages of chronic comorbidities were 1.8 (i.e., social QOL) to 4.5 (i.e., physical QOL) higher in the lowest QOL class compared to the highest QOL class.

The importance of personality was confirmed. Patients in the trajectories representing lower QOL (i.e., all QOL domains and the overall facet), had higher trait anxiety and neuroticism scores but lower scores on extraversion. Our results are in line with prior research [23,24,25]. However, one study [57] found no significant relationship between neuroticism and functional status in DRF assessed with the Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire [58]. However, we hypothesize that the relationship between personality is stronger for multidimensional outcome measures that take psychosocial functioning into consideration as well (i.e., HS and (HR)QOL measures) [20]. How satisfied patients are with their functioning (HR)QOL, in contrast to an assessment of functioning (HS), might be particularly influenced by enduring patterns in behavior, cognition, and emotion that is labeled personality [59].

Pain catastrophizing is an important health cognition to take into account when treating DRF and AF. Higher pain catastrophizing was found in trajectories representing lower QOL (i.e., all QOL domains and the overall QOL facet). Those few studies that reported on pain catastrophizing in relation to HS/HRQOL in musculoskeletal trauma patients (e.g., fractures), indicated that pain catastrophizing is a significant predictor of HS/HRQOL five to eight months post-injury [28, 29]. Additionally, some studies focused on the relationship between pain catastrophizing and functional status after DRF [60,61,62]. Significant negative relationships were reported between pain catastrophizing and functional status 4 weeks [60] and 3 months after DRF surgery [61] whereas this association was not found in non-operatively treated patients with DRF 6 weeks post-fracture [62]. Our study sample encompassed approximately half DRF and half AF. More than two-third of the patients was non-operatively treated, suggesting that pain catastrophizing is important for QOL in the whole group of patients with either DRF or AF.

A more prominent role for internal PLOC (i.e., significance for all QOL domains and the overall QOL facet) was found compared to external PLOC (i.e., significance for overall, physical, and environmental QOL). Therefore, the belief of being in control of one’s own health seems a powerful cognition with positive relationships with QOL. The direction of this relationship is in agreement with research reporting positive associations between internal HLOC and the level of daily living activities/self-rated health in patients with hip fractures or patients at risk for cardiovascular disease [34, 63]. In contrast to pain catastrophizing and PLOC, patients did not differ on pain coping between QOL classes. We expected a significantly higher variability of pain coping strategies in patients for the trajectories representing higher QOL. However, variability does not directly imply an effective employment of these strategies that may explain the lack of association with QOL. Therefore, this is a limitation of the pain coping subscale that was used [33]. A suggestion might be to incorporate pain coping in further research using a somewhat different approach by examining more specific forms of coping in relation to QOL in patients with fractures (i.e., instead of variability). For example, to examine the suitability of passive versus active coping [30] or possible differences between problem focused, emotional or avoidance coping in relation to QOL [31].

Another possible limitation of our study includes the retrospective measurement of patients’ pre-injury QOL, which may have introduced recall biases. An inflation of pre-injury QOL may occur by re-evaluating pre-injury QOL with reference to the injured status (i.e., response shift). It was found that retrospectively reported pre-injury scores of HS and HRQOL were consistently higher compared to population norms [64]. However, the QOL measurements three, six, and 12 months post-fracture are assumed to be completed with the same internal standard, with reference to the injured status, as Time-0retrospective. Therefore, although the possibility of a small upward bias should be considered, the usage of retrospectively measured pre-injury QOL may be more appropriate than general population norms [64, 65].

Latent class trajectory analysis was used as a technique to gather new insights in complex QOL data of patients with fractures. Therefore, our paper presents a pragmatic application of this statistical taxonomic method. We do not claim that the clusters that were derived present the real theoretical clustering. However, using this taxonomy, we found different QOL trajectories that were defined by several sociodemographic, clinical, and psychological characteristics. These new insights could eventually contribute to the possible identification of patients at risk in clinical practice. The program Latent GOLD and the technique latent class trajectory analysis has already been used in other research areas in a similar pragmatic manner (i.e., as an exploring technique to obtain new insights). For example, in the field of cardiology [66,67,68] and perinatology [69]. Latent GOLD produces the most optimal taxonomy based on the data that have been gathered. With a small sample, replication with the use of a new dataset could show a different taxonomy. However, our sample size (n = 543) is relatively large. Therefore, we can be more confident that the results are stable and replicable. The total variance (R 2) explained by our models ranged from 71.6 to 79.4%, which means that individual variation between patients and over time is predicted very well by the classes. In addition, possible bias was taken into account at forehand using the Step 3 method.

This study attempts to encourage clinicians to take a biopsychosocial perspective in the treatment of patients with AF and DRF. Firstly, knowledge of several sociodemographic characteristics of patients is already informative regarding their course of QOL after fracture. However, differentiation is important. In general, the characteristics are different depending on the QOL domain of interest. For example, trajectories of social QOL did only differ significantly on marital and employment status and not on age, sex, or educational level. However, age was significant for overall, physical, psychological, and environmental QOL showing a broad scope of influence. Secondly, results suggested that it is important to be alert towards chronic comorbidities, especially for patients’ physical QOL. The presence of chronic comorbidities seems more crucial than several injury-related clinical variables. Thirdly, this was the first study in patients with DRF and AF including several psychological characteristics, showing that trait anxiety, neuroticism, extraversion, pain catastrophizing, and internal PLOC are significantly different between QOL trajectories (i.e., all QOL domains and the facet). Based on these results, further QOL research is recommended in which psychological predictors (e.g., pain anxiety, general illness beliefs [60, 62, 70]) in addition to sociodemographic and clinical indicators are incorporated. Based on the identified characteristics related to QOL by this study and further research using the biopsychosocial model, patients at risk for low QOL after fracture may be recognized earlier by health care professionals and, therefore, could be better monitored. A more personalized approach can be used, for instance when patients are severely hampered by negative pain beliefs. They may be offered additional care in the form of a psychological intervention aimed to lower pain catastrophizing [71].

References

Wilcke, M. K., Hammarberg, H., & Adolphson, P. Y. (2013). Epidemiology and changed surgical treatment methods for fractures of the distal radius: A registry analysis of 42,583 patients in Stockholm County, Sweden, 2004-2010. Acta Orthopaedica, 84(3), 292–296.

Mellstrand-Navarro, C., Pettersson H. J., Tornqvist, H., & Ponzer, S. (2014). The operative treatment of fractures of the distal radius is increasing: Results from a nationwide Swedish study. The Bone and Joint Journal, 96-b(7), 963–969.

Brogren, E., Petranek, M., & Atroshi, I. (2007). Incidence and characteristics of distal radius fractures in a southern Swedish region. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 8, 48.

Court-Brown, C. M., & Caesar, B. (2006). Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review. Injury, 37(8), 691–697.

Makhni, E. C., Ewald T. J., Kelly, S., & Day, C. S. (2008). Effect of patient age on the radiographic outcomes of distal radius fractures subject to nonoperative treatment. The Journal of Hand Surgery, 33(8), 1301–1308.

Nesbitt, K. S., Failla, J. M., & Les, C. (2004). Assessment of instability factors in adult distal radius fractures. The Journal of Hand Surgery America, 29(6), 1128–1138.

Leung, F., Ozkan, M., & Chow, S. P. (2000). Conservative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the distal radius–factors affecting functional outcome. Hand Surgery, 5(2), 145–153.

Shah, N. H., Sundaram, R. O., Velusamy, A., & Braithwaite, I. J. (2007). Five-year functional outcome analysis of ankle fracture fixation. Injury, 38(11), 1308–1312.

Hong, C. C., Roy, S. P., Nashi, N., & Tan, K. J. (2013). Functional outcome and limitation of sporting activities after bimalleolar and trimalleolar ankle fractures. Foot and Ankle International, 34(6), 805–810.

Byl, N. N., Kohlhase, W., & Engel, G. (1999). Functional limitation immediately after cast immobilization and closed reduction of distal radius fractures: Preliminary report. Journal of Hand Therapy, 12(3), 201–211.

Brogren, E., Hofer, M., Petranek, M., Dahlin, L. B., & Atroshi, I. (2011). Fractures of the distal radius in women aged 50 to 75 years: Natural course of patient-reported outcome, wrist motion and grip strength between 1 year and 2–4 years after fracture. The Journal of hand surgery European, 36(7), 568–576.

Shulman, B. S., Liporace, F. A., Davidovitch, R. I., Karia, R., & Egol, K. A. (2014). Sleep disturbance following fracture is related to emotional well being rather than functional result. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 29(3), e146–e150.

Thakore, R. V., Hooe, B. S., Considine, P., Sathiyakumar, V., Onuoha, G., Hinson, J. K., et al. (2015). Ankle fractures and employment: A life-changing event for patients. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(5), 417–422.

MacDermid, J. C., Roth, J. H., & McMurtry, R. (2007). Predictors of time lost from work following a distal radius fracture. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 17(1), 47–62.

van der Sluis, C. K., Eisma, W. H., Groothoff, J. W., & ten Duis, H. J. (1998). Long-term physical, psychological and social consequences of a fracture of the ankle. Injury, 29(4), 277–280.

WHOQOLGroup. (1995). The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science & Medicine, 41(10), 1403–1409.

WHOQOLGroup. (1998). The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Social Science & Medicine, 46(12), 1569–1585.

WHOQOLGroup. (1994). Development of the WHOQOL: Rationale and current status. International Journal of Mental Health, 23(3), 24–56.

De Vries, J. (2001). Quality of life assessment. In A. J. J. M. Vingerhoets (Ed.), Assessment in behavorial medicine (pp. 353–370). Hove: Brunner-Routledge.

Moons, P. (2004). Why call it health-related quality of life when you mean perceived health status? European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 3(4), 275–277.

Van Son, M. A., De Vries, J., Roukema, J. A., & Den Oudsten, B. L. (2013). Health status and (health-related) quality of life during the recovery of distal radius fractures: A systematic review. Quality of Life Research, 22(9), 2399–2416.

Van Son, M. A., De Vries, J., Roukema, J. A., & Den Oudsten, B. L. (2013). Health status, health-related quality of life, and quality of life following ankle fractures: A systematic review. Injury, 44(11), 1391–1402.

Montin, L., Leino-Kilpi, H., Katajisto, J., Lepisto, J., Kettunen, J., & Suominen, T. (2007). Anxiety and health-related quality of life of patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. Chronic Illness, 3(3), 219–227.

Gong, L., & Dong, J. Y. (2014). Patient’s personality predicts recovery after total knee arthroplasty: A retrospective study. Journal of Orthopaedic Science, 19(2), 263–269.

Scholich, S. L., Hallner, D., Wittenberg, R. H. Hasenbring, M. I., & Rusu, A. C. (2012). The relationship between pain, disability, quality of life and cognitive-behavioural factors in chronic back pain. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(23), 1993–2000.

van der Steeg, A. F., De Vries, J., van der Ent, F. W., & Roukema, J. A. (2007). Personality predicts quality of life six months after the diagnosis and treatment of breast disease. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 14(2), 678–685.

Sullivan, M. J., & Bishop, L. S. (1995). The pain catastrophizing scale: Developmend and validation. Psychological Assessment, 7, 524–532.

Nota, S. P., Bot, A. G., Ring, D., & Kloen, P. (2015). Disability and depression after orthopaedic trauma. Injury, 46(2), 207–212.

Vranceanu, A. M., Bachoura, A., Weening, A., Vrahas, M., Smith, R. M., Ring, D. (2014). Psychological factors predict disability and pain intensity after skeletal trauma. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume, 96(3), e20.

Carroll, L. J., Cassidy, J. D., & Cote, P. (2006). The role of pain coping strategies in prognosis after whiplash injury: Passive coping predicts slowed recovery. Pain, 124(1–2), 18–26.

Aarstad, A. K., Beisland, E., Osthus, A. A., & Aarstad, H. J. (2011). Distress, quality of life, neuroticism and psychological coping are related in head and neck cancer patients during follow-up. Acta Oncologica, 50(3), 390–398.

Wallston, K. A., Wallston, B. S., & DeVellis, R. (1978). Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Health Education Monographs, 6(2), 160–170.

De Gier, M., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., Van Breukelen, G., Stomp, S. G. M., Ter Kuile, M. M., Kole-Snijders, A. M. J., et al. (2004). Meetinstrumenten chronische pijn: Deel 3 Pijn Coping en Cognitie Lijst validering en normgegevens. Pijn Kennis Centrum: Maastricht.

Roberto, K. A., & Bartmann, J. (1993). Factors related to older women’s recovery from hip fractures: Physical ability, locus of control, and social support. Health Care for Women International, 14(5), 457–468.

Müller, M., Nazarian, S., Koch, P., & Schatzker, J. (1990). The comprehensive classification of fractures of long bones. Berlin: Springer.

WHOQOLGroup. (1998). Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychological Medicine, 28(3), 551–558.

Taylor, W. J., Myers, J., Simpson, R. T., McPherson, K. M., & Weatherall, M. (2004). Quality of life of people with rheumatoid arthritis as measured by the World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument, short form (WHOQOL-BREF): Score distributions and psychometric properties. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 51(3), 350–357.

Jang, Y., Hsieh, C. L., Wang, Y. H., & Wu, Y. H. (2004). A validity study of the WHOQOL-BREF assessment in persons with traumatic spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85(11), 1890–1895.

Van Esch, L., Den Oudsten, B. L., & De Vries, J. (2011). The World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument-Short Form (WHOQOL-BREF) in women with breast problems. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 11(1), 5–22.

De Vries, J. (1996). Beyond health status: Construction and validation of the Dutch WHO quality of life asssessment instrument. Tilburg: Tilburg University.

Trompenaars, F. J., Masthoff, E. D., Van Heck, G. L., Hodiamont, P. P., & De Vries, J. (2005). Content validity, construct validity, and reliability of the WHOQOL-Bref in a population of Dutch adult psychiatric outpatients. Quality of Life Research, 14(1), 151–160.

Stomp-Van den Berg, S. G. M., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., Ter Kuile, M. M., Spinhoven, P., Van Breukelen, G., & Kole-Snijders, A. M. J. (2001). Meetinstrumenten chronische pijn: Deel 2 Pijn Coping en Cognitie Lijst (PCCL). Maastricht: Pijn Kennis Centrum.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and the five factor inventory (NEO-FFI): Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Hoekstra, H. A., Ormel, J., & De Fruyt, F. (1996). Handleiding bij de NEO Persoonlijkheidsvragenlijsten NEO-PI-R en NEO-FFI. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1989). The NEO-PI/NEO-FFI manuel supplement. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

De Vries, J., & Van Heck, G. L. (2013). Development of a short version of the Dutch version of the Spielberger STAI trait anxiety scale in women suspected of breast cancer and breast cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 20(2), 215–226.

Van Der Ploeg, H. M., Defares, P. B., & Spielberger, C. D. (1980). Handleiding bij de Zelf Beoordelings Vragenlijst ZBV: Een Nederlandstalige bewerking van de Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI-DY. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1970). The state-trait anxiety inventory manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1968). State-trait anxiety inventory: Preliminary test manual for form X. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida State University.

Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2013). Technical guide for Latent GOLD 5.0: Basic, advanced, and syntax. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations Inc.

Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2013). Latent GOLD 5.0. Upgrade manual. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations Inc.

Vermunt, J. K., & Magidson, J. (2013). Latent GOLD 4.0 user’s guide. 2005. Belmont, MA: Statistical Innovations Inc.

Nilsson, G., Jonsson, K., Ekdahl, C., & Eneroth, M. (2007). Outcome and quality of life after surgically treated ankle fractures in patients 65 years or older. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 8, 127.

Gruber, G., Zacherl, M., Giessauf, C., Glehr, M., Fuerst, F. Liebmann, W., et al. (2010). Quality of life after volar plate fixation of articular fractures of the distal part of the radius. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume, 92(5), 1170–1178.

Bhandari, M., Sprangue, S., Hanson, B., Busse, J. W., Dawe, D. E., Moro, J. K., et al. (2004). Health-related quality of life following operative treatment of unstable ankle fractures: A prospective observational study. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 18(6), 338–345.

Rohde, G., Haugeberg, G., Mengshoel, A. M., Moum, T., & Wahl, A. K. (2009). No long-term impact of low-energy distal radius fracture on health-related quality of life and global quality of life: A case-control study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 10, 106.

Ring, D., Kadzielski, J., Fabian, L., Zurakowski, D., Malhotra, L. R., Jupiter, J. B. (2006). Self-reported upper extremity health status correlates with depression. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume, 88(9), 1983–1988.

Hudak, P. L., Amadio, P. C., & Bombardier, C. (1996). Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: The DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG). American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 29(6), 602–608.

Larsen, R. J., & Buss, D. M. (2005). Personality psychology: Domains of knowledge about human nature (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Roh, Y. H., Lee, B. K., Noh, J. H., Oh, J. H., Gong, H. S., & Baek, G. H. (2014). Effect of anxiety and catastrophic pain ideation on early recovery after surgery for distal radius fractures. Journal of Hand Surgery America, 39(11), 2258.

Bot, A. G., Souer, J. S., van Dijk, C. N., & Ring, D. (2012). Association between individual DASH tasks and restricted wrist flexion and extension after volar plate fixation of a fracture of the distal radius. Hand (N Y), 7(4), 407–412.

Bot, A. G., Mulders, M. A., Fostvedt, S., & Ring, D. (2012). Determinants of grip strength in healthy subjects compared to that in patients recovering from a distal radius fracture. Journal of Hand Surgery America, 37(9), 1874–1880.

Berglund, E., Lytsy, P., & Westerling, R. (2014). The influence of locus of control on self-rated health in context of chronic disease: A structural equation modeling approach in a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health, 14, 492.

Watson, W. L., Ozanne-Smith, J., & Richardson, J. (2007). Retrospective baseline measurement of self-reported health status and health-related quality of life versus population norms in the evaluation of post-injury losses. Injury Prevention, 13(1), 45–50.

Wilson, R., Derrett, S., Hansen, P., & Langley, J. (2012). Retrospective evaluation versus population norms for the measurement of baseline health status. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10, 68.

Mastenbroek, M. H., Denollet, J., Versteeg, H., van den Broek, K. C., Theuns, D. A., & Meine, M., et al. (2015). Trajectories of patient-reported health status in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. American Journal of Cardiology, 115(6), 771–777.

Mastenbroek, M. H., Pedersen, S. S., Meine, M., & Versteeg, H. (2016). Distinct trajectories of disease-specific health status in heart failure patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. Quality of Life Research, 25(6), 1451–1460.

Duivis, H. E., Kupper, H. M., Vermunt, J. K., Penninx, B. W., Bosch, N. M., Riese, H., et al. (2015). Depression trajectories, inflammation, and lifestyle factors in adolescence: The TRacking Adolescents’ Individual Lives Survey. Health Psychology, 34(11), 1047–1057.

Mulder, E. J., Koopman, C. M., Vermunt, J. K., de Valk, H. W., & Visser, G. H. (2010). Fetal growth trajectories in Type-1 diabetic pregnancy. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 36(6), 735–742.

Busse, J. W., Bhandari, M., Guyatt, G. H., Heels-Ansdell, D., Kulkarni, A. V., & Mandel, S., et al. (2012). Development and validation of an instrument to predict functional recovery in tibial fracture patients: The Somatic Pre-Occupation and Coping (SPOC) questionnaire. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 26(6), 370–378.

Riddle, D. L., Keefe, F. J., Nay, W. T., McKee, D., Attarian, D. E., & Jensen, M. P. (2011). Pain coping skills training for patients with elevated pain catastrophizing who are scheduled for knee arthroplasty: A quasi-experimental study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92(6), 859–865.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Son, M.A.C., De Vries, J., Zijlstra, W. et al. Trajectories in quality of life of patients with a fracture of the distal radius or ankle using latent class analysis. Qual Life Res 26, 3251–3265 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1670-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1670-x