Abstract

Purpose

This study explores variation in health state descriptions and valuations derived from preference-based health-related quality of life instruments in the context of spinal cord injury (SCI).

Methods

Individuals living with SCI were invited to complete a web-based, cross-sectional survey. The survey comprised questions regarding demographics, SCI classifications and characteristics, secondary health complications and conditions, quality of life and SCI-specific functioning in activities of daily living. Four preference-based health status classification systems were included; Assessment of Quality of Life 8-dimension questionnaire (AQoL-8D), EQ-5D-5L, Health Utilities Index (HUI) and SF-6D (derived from the SF-36v2). In addition to descriptive comparisons of index scores and item/dimension responses, analyses explored dimension-level correlation and absolute agreement (intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)). Subgroup analyses examined the influence of individuals’ self-reported ability to walk.

Results

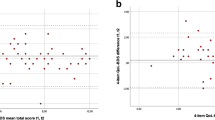

Of 609 invitations, 364 (60 %) individuals completed the survey. Across instruments, convergent validity was seen between pain and mental health dimensions, while sizeable variation pertaining to issues of mobility was observed. Mean index scores were 0.248 (HUI-3), 0.492 (EQ-5D-5L), 0.573 (AQoL-8D) and 0.605 (SF-6D). Agreement ranged from ‘slight’ (HUI-3 and SF-6D; ICC = 0.124) to ‘moderate’ (AQoL-8D and SF-6D; ICC = 0.634). Walking status had a markedly different impact on health state valuations across instruments.

Conclusions

Variation in the way that individuals are able to describe their health state across instruments is not unique to SCI. Further research is necessary to understand the significant differences in index scores and, in particular, the implications of framing mobility-related questions in the context of respondents’ ability to walk.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Neumann, P., Goldie, S. J., & Weinstein, M. C. (2000). Preference-based measures in economic evaluation in health care. Annual Review of Public Health, 21, 587–611.

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. (2006). Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies: Canada (3rd ed.). Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2013). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Statistics Canada. (2011). Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), 2010 Annual Component surveys. Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada.

Richardson, J., McKie, J., & Bariola, E. (2014). Multiattribute Utility instruments and their use. In A. J. Culyer (Ed.), Encyclopedia of health economics (pp. 41–57). San Diego, CA: Elsevier.

Brooks, R. (1996). EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy, 37(1), 53–72.

Torrance, G. W., Feeny, D. H., Furlong, W. J., Barr, R. D., Zhang, Y., & Wang, Q. (1996). Multiattribute utility function for a comprehensive health status classification system. Health Utilities Index Mark 2. Medical Care, 34(7), 702–722.

Feeny, D., Furlong, W., Torrance, G. W., Goldsmith, C. H., Zhu, Z., DePauw, S., et al. (2002). Multi attribute and single attribute utility functions for the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 System. Medical Care, 40(2), 113–128.

Brazier, J., Roberts, J., & Deverill, M. (2002). The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. Journal of Health Economics, 21(2), 271–292.

Brazier, J. E., & Roberts, J. (2004). The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Medical Care, 42(9), 851–859.

Sintonen, H. (2001). The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: Properties and applications. Annals of Medicine, 33(5), 328–336.

Hawthorne, G., Richardson, J., & Osborne, R. (1999). The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) instrument: A psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 8(3), 209–224.

The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) instruments. Melbourne (Australia): Centre for Health Economics. Accessed August 31, 2015. http://www.aqol.com.au/index.php/aqolinstruments.

Kaplan, R. M., Anderson, J. P., & Ganiats, T. G. (1993). The Quality of Well-being Scale: Rationale for a single quality of life index. In S. R. Walker & R. M. Rosser (Eds.), Quality of life assessment: Key issues in the 1990s (pp. 65–94). London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Fryback, D. G., Palta, M., Cherepanov, D., Bolt, D., & Kim, J. (2010). Comparison of 5 health related quality of life indexes using item response theory analysis. Medical Decision Making, 30(1), 5–15.

Whitehurst, D. G. T., Bryan, S., & Lewis, M. (2011). Systematic review and empirical comparison of contemporaneous EQ-5D and SF-6D group mean scores. Medical Decision Making, 31(6), E34–E44.

Moock, J., & Kohlmann, T. (2008). Comparing preference-based quality-of-life measures: Results from rehabilitation patients with musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, or psychosomatic disorders. Quality of Life Research, 17(3), 485–495.

Richardson, J., Khan, M. A., Iezzi, A., & Maxwell, A. (2015). Comparing and explaining differences in the magnitude, content, and sensitivity of utilities predicted by the EQ-5D, SF-6D, HUI 3, 15D, QWB, and AQoL-8D multiattribute utility instruments. Medical Decision Making, 35(3), 276–291.

Grieve, R., Grishchenko, M., & Cairns, J. (2009). SF-6D versus EQ-5D: Reasons for differences in utility scores and impact on reported cost-utility. The European Journal of Health Economics, 10, 15–23.

Whitehurst, D. G., & Bryan, S. (2011). Another study showing that two preference-based measures of health-related quality of life (EQ-5D and SF-6D) are not interchangeable. But why should we expect them to be? Value Health, 14(4), 531–538.

Konerding, U., Moock, J., & Kohlmann, T. (2009). The classification systems of the EQ-5D, the HUI II and the SF-6D: What do they have in common? Quality of Life Research, 18, 1249–1261.

Espallargues, M., Czoski-Murray, C. J., Bansback, N. J., Carlton, J., Lewis, G. M., Hughes, L. A., et al. (2005). The impact of age-related macular degeneration on health status utility values. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science, 46(11), 4016–4023.

Whitehurst, D. G. T., Noonan, V. K., Dvorak, M. F. S., & Bryan, S. (2012). A review of preference-based health-related quality of life questionnaires in spinal cord injury research. Spinal Cord, 50(9), 646–654.

Andresen, E. M., Fouts, B. S., Romeis, J. C., & Brownson, C. A. (1999). Performance of health-related quality-of-life instruments in a spinal cord injured population. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 80(8), 877–884.

Lee, B. B., Simpson, J. M., King, M. T., Haran, M. J., & Marial, O. (2009). The SF-36 walk-wheel: A simple modification of the SF-36 physical domain improves its responsiveness for measuring health status change in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 47(1), 50–55.

Engel, L., Bryan, S., Evers, S. M., Dirksen, C. D., Noonan, V. K., & Whitehurst, D. G. (2014). Exploring psychometric properties of the SF-6D, a preference-based health-related quality of life measure, in the context of spinal cord injury. Quality of Life Research, 23(8), 2383–2393.

Craven, C., Hitzig, S. L., & Mittmann, N. (2012). Impact of impairment and secondary health conditions on health preference among Canadians with chronic spinal cord injury. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 35(5), 361–370.

Richardson, J., Iezzi, A., Khan, M. A., & Maxwell, A. (2014). Validity and reliability of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient, 7(1), 85–96.

Herdman, M., Gudex, C., Lloyd, A., Janssen, M., Kind, P., Parkin, D., et al. (2011). Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of Life Research, 20(10), 1727–1736.

Seiber WJ, Groessl EJ, David KM, Ganiats TG, Kaplan RM (2008) Quality of well being self-administered (QWB-SA) scale user’s manual. San Diego, CA: Health Services Research Center. Accessed August 31, 2015. https://hoap.ucsd.edu/qwb-info/QWB-Manual.pdf.

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., Bjorner, J. B., Turner-Bowker, D. M., Gandek, B., & Maruish, M. E. (2007). User’s manual for the SF-36v2TM health survey (2nd ed.). Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric.

Whitehurst, D. G., Suryaprakash, N., Engel, L., Mittmann, N., Noonan, V. K., Dvorak, M. F., et al. (2014). Perceptions of individuals living with spinal cord injury toward preference-based quality of life instruments: A qualitative exploration. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 12, 50.

Noreau, L., Noonan, V. K., Cobb, J., Leblond, J., & Dumont, F. S. (2014). Spinal cord injury community survey: A national, comprehensive study to portray the lives of Canadians with spinal cord injury. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 20(4), 249–264.

Brazier, J. E., Rowen, D., & Hanmer, J. (2008). Revised SF-6D scoring programmes: A summary of improvements. PRO Newsletter, 40, 14–15.

Perreault, W. D. (1975). Controlling order-effect bias. Public Opinion Quarterly, 39(4), 544–551.

Xie, F., Pullenayegum, E., Gaebel, K., Bansback, N., Bryan, S., Ohinmaa, A., et al. (2016). Canadian EQ-5D-5L Valuation Study Group. A time trade-off-derived value set of the EQ-5D-5L for Canada. Medical Care, 54(1), 98–105.

Brazier, J., Roberts, J., Tsuchiya, A., & Busschbach, J. (2004). A comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-6D across seven patient groups. Health Economics, 13(9), 873–884.

Shrout, P. E., & Fleiss, J. L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86(2), 420–427.

Shrout, P. E. (1998). Measurement reliability and agreement in psychiatry. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 7(3), 301–317.

Hanmer, J., Cherepanov, D., Palta, M., Kaplan, R. M., Feeny, D., & Fryback, D. G. (2016). Health condition impacts in a nationally representative cross-sectional survey vary substantially by preference-based health index. Medical Decision Making, 36(2), 264–274.

Heintz, E., Wiréhn, A. B., Peebo, B. B., Rosenqvist, U., & Levin, L. Å. (2012). QALY weights for diabetic retinopathy: A comparison of health state valuations with HUI-3, EQ-5D, EQ-VAS, and TTO. Value Health, 15(3), 475–484.

Joore, M., Brunenberg, D., Nelemans, P., Wouters, E., Kuijpers, P., Honig, A., et al. (2010). The impact of differences in EQ-5D and SF-6D utility scores on the acceptability of cost-utility ratios: Results across five trial-based cost-utility studies. Value Health, 13(2), 222–229.

Mihalopoulos, C., Chen, G., Iezzi, A., Khan, M. A., & Richardson, J. (2014). Assessing outcomes for cost-utility analysis in depression: comparison of five multi-attribute utility instruments with two depression-specific outcome measures. British Journal of Psychiatry, 205(5), 390–397.

Richardson, J., Chen, G., Khan, M. A., & Iezzi, A. (2015). Can multi-attribute utility instruments adequately account for subjective well-being? Medical Decision Making, 35(3), 292–304.

Richardson, J., Iezzi, A., & Khan, M. A. (2015). Why do multi-attribute utility instruments produce different utilities: The relative importance of the descriptive systems, scale and ‘micro-utility’ effects. Quality of Life Research, 24(8), 2045–2053.

Whitehurst, D. G., Norman, R., Brazier, J. E., & Viney, R. (2014). Comparison of contemporaneous EQ-5D and SF-6D responses using scoring algorithms derived from similar valuation exercises. Value Health, 17(5), 570–577.

Hays, R. D., Siu, A. L., Keeler, E., Marshall, G. N., Kaplan, R. M., Simmons, S., et al. (1996). Long-term care residents’ preferences for health states on the quality of well-being scale. Medical Decision Making, 16(3), 254–261.

Yang, Y., Rowen, D., Brazier, J., Tsuchiya, A., Young, T., & Longworth, L. (2015). An exploratory study to test the impact on three “bolt-on” items to the EQ-5D. Value Health, 18(1), 52–60.

Tosh, J., Brazier, J., Evans, P., & Longworth, L. (2012). A review of generic preference-based measures of health-related quality of life in visual disorders. Value Health, 15(1), 118–127.

Kaplan, R. M., Tally, S., Hays, R. D., Feeny, D., Ganiats, T. G., Palta, M., et al. (2011). Five preference-based indexes in cataract and heart failure patients were not equally responsive to change. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(5), 497–506.

Feeny, D., Spritzer, K., Hays, R. D., Liu, H., Ganiats, T. G., Kaplan, R. M., et al. (2012). Agreement about identifying patients who change over time: Cautionary results in cataract and heart failure patients. Medical Decision Making, 32(2), 273–286.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from the Rick Hansen Institute (Rick Hansen Institute Translational Research Program, Grant #2012-29: Spinal Cord Injury and Secondary Complications: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation of Preference-Based Instruments). The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing and publishing the report. We would also like to thank Health Utilities Inc. for the New Investigator Grant awarded to Dr. David Whitehurst, Dr. Davene Wright for her discussion of an early draft of this paper at the 2015 Vancouver Health Economics Methodology (VanHEM) meeting, Lidia Engel for her assistance with generating Fig. 1, and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and comprehensive comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board (H12-01138) and Vancouver Coastal Health Authority (Research Study #V12-01138).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Distribution of responses to item 3 (‘getting around’; Panel A) and item 15 (‘mobility’; Panel B) of the AQoL-8D for the subsample of individuals indicating that they are unable to walk (n = 245). The subsample of 245 was defined as those individuals who reported level five on the EQ-5D-5L Mobility dimension (‘I am unable to walk’; n = 261) and level six on the HUI-3 Ambulation dimension (‘Unable to walk at all’; n = 251). Cohen’s kappa statistic for the level of agreement in self-reported walking status for the EQ-5D-5L and HUI-3 (i.e. after dichotomizing both variables, into ‘able to walk’ and ‘unable to walk’ categories) = 0.86.

Appendix 2

Mean (SD) SF-36v2 Physical Component Summary (PCS) scores by dimension response level for the EQ-5D-5L, SF-6D and HUI-3.

Instrument | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dimension (items) | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 | Level 6 |

EQ-5D-5L | ||||||

Mobility* | 50.04 (6.6) | 41.17 (6.9) | 35.35 (6.3) | 28.77 (6.5) | 33.74 (8.0) | – |

Self-care* | 38.33 (8.4) | 32.98 (7.6) | 30.37 (6.8) | 32.56 (8.8) | 31.95 (7.8) | – |

Usual Activities* | 41.00 (8.7) | 35.85 (6.4) | 30.76 (6.4) | 28.55 (7.4) | 32.15 (9.4) | – |

Pain/Discomfort* | 42.46 (7.8) | 38.81 (7.2) | 32.24 (6.6) | 27.86 (5.9) | 23.89 (4.5) | – |

Anxiety/Depression | 34.67 (8.9) | 34.51 (8.3) | 31.73 (6.7) | 33.98 (9.3) | 43.68 (–) | – |

HUI-3 | ||||||

Vision | 35.25 (9.0) | 33.57 (8.2) | 32.67 (6.1) | 29.65 (7.7) | 35.66 (4.6) | 40.45 (–) |

Hearing | 34.11 (8.5) | 31.72 (7.8) | 34.32 (8.1) | 33.64 (8.2) | 35.75 (–) | 33.03 (5.6) |

Speech | 34.22 (8.5) | 32.92 (6.6) | 29.91 (5.6) | 25.74 (–) | NR | – |

Emotion** | 35.40 (8.4) | 33.77 (8.3) | 32.28 (7.9) | 31.83 (9.5) | 30.98 (8.7) | – |

Pain* | 42.55 (7.4) | 37.24 (7.5) | 32.15 (6.7) | 28.20 (6.6) | 25.19 (3.6) | – |

Ambulation* | 49.68 (6.7) | 36.06 (5.3) | 35.85 (6.6) | 30.63 (7.6) | 27.81 (3.4) | 33.97 (8.2) |

Dexterity | 35.24 (8.6) | 33.21 (7.7) | 33.64 (7.1) | 33.12 (8.3) | 29.97 (7.6) | 33.78 (9.8) |

Cognition** | 34.77 (8.5) | 31.16 (8.0) | 34.63 (8.5) | 29.75 (6.6) | 33.24 (8.1) | NR |

SF-6D | ||||||

Physical Functioning* | 48.10 (6.4) | 45.13 (8.3) | 39.01 (6.5) | 33.91 (6.8) | 32.30 (7.04) | 31.06 (7.6) |

Role Limitations* | 45.17 (6.5) | 31.06 (8.1) | 43.35 (4.1) | 32.84 (7.1) | – | – |

Pain* | 43.60 (7.2) | 40.31 (7.2) | 36.27 (7.0) | 31.27 (5.6) | 27.31 (6.2) | 26.64 (6.2) |

Vitality* | 43.61 (4.0) | 37.65 (7.8) | 34.38 (7.3) | 31.33 (9.2) | 29.56 (6.6) | – |

Mental Health | 35.76 (9.0) | 33.62 (8.5) | 33.33 (7.3) | 33.43 (8.5) | 36.13 (11.6) | – |

Social Functioning* | 39.36 (7.5) | 36.40 (7.6) | 30.99 (7.3) | 30.25 (7.8) | 28.90 (7.9) | – |

Appendix 3

Mean (SD) SF-36v2 Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores by dimension response level for the EQ-5D-5L, SF-6D and HUI-3.

Instrument | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dimension (items) | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 | Level 6 |

EQ-5D-5L | ||||||

Mobility* | 45.58 (15.0) | 45.15 (11.4) | 46.96 (11.4) | 48.41 (13.4) | 52.36 (11.8) | – |

Self-care | 52.74 (12.0) | 48.73 (11.5) | 49.65 (12.2) | 50.79 (15.3) | 51.54 (11.8) | – |

Usual Activities* | 55.82 (11.3) | 53.33 (10.3) | 49.52 (11.4) | 45.38 (13.2) | 43.15 (15.1) | – |

Pain/Discomfort* | 56.32 (12.5) | 53.19 (10.9) | 52.10 (12.0) | 45.87 (12.3) | 43.53 (12.6) | – |

Anxiety/Depression* | 58.38 (8.2) | 50.92 (8.8) | 39.76 (8.6) | 28.83 (10.4) | 10.34 (–) | – |

HUI-3 | ||||||

Vision | 51.44 (11.9) | 50.98 (12.1) | 43.25 (8.4) | 38.24 (15.0) | 54.94 (16.6) | 59.96 (–) |

Hearing | 51.28 (12.1) | 53.82 (17.8) | 50.92 (12.7) | 44.73 (10.8) | 61.34 (–) | 37.64 (8.3) |

Speech* | 51.52 (11.9) | 41.52 (13.9) | 38.88 (9.6) | 27.44 (–) | NR | – |

Emotion* | 59.71 (7.0) | 50.04 (8.3) | 37.80 (9.0) | 32.59 (12.2) | 26.69 (5.5) | – |

Pain* | 57.36 (11.8) | 54.57 (9.8) | 48.86 (12.2) | 46.53 (12.3) | 37.31 (10.5) | – |

Ambulation* | 43.97 (13.6) | 42.58 (9.4) | 48.69 (10.8) | 51.15 (12.6) | 44.25 (12.0) | 52.26 (12.0) |

Dexterity | 50.60 (12.7) | 47.70 (11.9) | 52.44 (11.5) | 52.28 (10.7) | 54.44 (12.1) | 49.13 (11.4) |

Cognition* | 53.83 (11.4) | 46.56 (9.9) | 48.76 (9.7) | 39.62 (9.5) | 31.27 (11.0) | NR |

SF-6D | ||||||

Physical Functioning | 55.75 (8.6) | 47.95 (16.0) | 54.45 (8.8) | 51.45 (11.9) | 48.88 (12.6) | 52.18 (11.9) |

Role Limitations* | 60.31 (7.2) | 62.18 (4.8) | 50.17 (9.8) | 44.94 (10.8) | – | – |

Pain* | 54.49 (14.1) | 57.38 (8.4) | 53.91 (11.4) | 50.32 (8.9) | 44.60 (11.6) | 36.94 (13.5) |

Vitality* | 65.27 (5.8) | 59.87 (6.8) | 53.35 (8.3) | 44.44 (10.6) | 36.24 (11.9) | – |

Mental Health* | 62.61 (5.6) | 55.08 (7.1) | 45.30 (7.4) | 34.66 (10.0) | 24.58 (10.5) | – |

Social Functioning* | 61.47 (6.4) | 54.16 (8.2) | 48.44 (9.7) | 40.76 (10.8) | 29.24 (10.9) | – |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whitehurst, D.G.T., Mittmann, N., Noonan, V.K. et al. Health state descriptions, valuations and individuals’ capacity to walk: a comparative evaluation of preference-based instruments in the context of spinal cord injury. Qual Life Res 25, 2481–2496 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1297-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1297-3