Abstract

Purpose

In cancer research, outcome measures may co-vary. Treatment and treatment related impairment of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) may affect survival. When these effects are analyzed separately, bias may arise. Therefore, we investigated the combined effect of treatment and longitudinally measured HRQoL on survival.

Methods

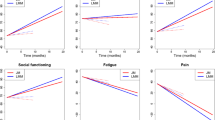

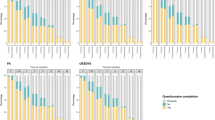

Patients with anaplastic oligodendrogliomas (n = 288) who were randomized (EORTC 26951) to radiotherapy (RT) alone or RT plus procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine (PCV) chemotherapy were analyzed. HRQoL [appetite loss (AP)] was assessed with the EORTC QLQ-C30. We compared survival results from different analysis strategies: Cox model with treatment only [model 1 (M1)] or with treatment and time-dependent AP score [model 2 (M2)] and the joint model combining longitudinal AP score and survival [model 3 (M3)].

Results

The estimated hazard ratio (HR) for RT plus PCV was 0.76 (95 % CI 0.58–1.00) for M1, 0.72 (0.55–0.96) for M2, and 0.69 (0.52–0.92) for M3. This corresponds to a lower risk of death of 24 % in M1, 28 % in M2, and 31 % in M3, for patients treated with RT plus PCV chemotherapy. AP resulted in an increased risk of death, with estimated HR of 1.06 (1.01–1.12) for M2 and 1.13 (1.03–1.23) for M3: Every 10-point increase of AP resulted in a 13 % increased risk of death in M3 as compared to 6 % in M2.

Conclusion

Part of the survival benefit of treatment with RT plus PCV chemotherapy can be masked by the negative effect that this treatment has on patients’ HRQoL. In our study, up to 7 % of the theoretical treatment efficacy was lost when AP was not adjusted through joint modeling.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gotay, C. C., Kawamoto, C. T., Bottomley, A., & Efficace, F. (2008). The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26, 1355–1363.

Quinten, C., Coens, C., Mauer, M., et al. (2009). Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet, 10, 865–871.

Eton, D. T., Fairclough, D. L., Cella, D., Yount, S. E., Bonomi, P., & Johnson, D. H. (2003). Early change in patient-reported health during lung cancer chemotherapy predicts clinical outcomes beyond those predicted by baseline report: Results from Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study 5592. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21, 1536–1543.

Deslandes, E., & Chevret, S. (2010). Joint modeling of multivariate longitudinal data and the dropout process in a competing risk setting: Application to ICU data. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 10, 69.

Wu, L., Liu, W., Yi, G. Y., & Huang, Y. (2012). Analysis of longitudinal and survival data: Joint modeling, inference methods, and issues. Journal of Probability and Statistics, 2012, 17. doi:10.1155/2012/640153.

Ibrahim, J. G., Chu, H., & Chen, L. M. (2010). Basic concepts and methods for joint models of longitudinal and survival data. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 2796–2801.

Rizopoulos, D. (2012). Joint models for longitudinal and time-to-event data: With applications in R. London: Chapman & Hall/CRC Biostatistics Series.

Wu, M., & Caroll, R. (1988). Estimation and comparison of changes in the presence of informative right censoring by modelling the censoring process. Biometrics, 44, 175–188.

Hogan, J. W., & Laird, N. M. (1997). Model-based approaches to analysing incomplete longitudinal and failure time data. Statistics in Medicine, 16, 259–272.

Faucett, C. L., & Thomas, D. C. (1996). Simultaneously modelling censored survival data and repeatedly measured covariates: A Gibbs sampling approach. Statistics in Medicine, 15, 1663–1685.

Henderson, R., Diggle, P., & Dobson, A. (2000). Joint modelling of longitudinal measurements and event time data. Biostatistics, 1, 465–480.

Song, X., Davidian, M., & Tsiatis, A. (2002). An estimator for the proportional hazards model with multiple longitudinal covariates measured with error. Biostatistics, 3, 511–528.

Touloumi, G., Babiker, A. G., Kenward, M. G., Pocock, S. J., & Darbyshire, J. H. (2003). A comparison of two methods for the estimation of precision with incomplete longitudinal data, jointly modelled with a time-to-event outcome. Statistics in Medicine, 22, 3161–3175.

Jacqmin-Gadda, H., Thiebaut, R., & Dartigues, J. F. (2004). Joint modeling of quantitative longitudinal data and censored survival time. RESP, 52, 502–510.

Thiebaut, R., Jacqmin-Gadda, H., Babiker, A., & Commenges, D. (2005). CASCADE collaboration. Joint modelling of bivariate longitudinal data with informative dropout and left-censoring, with application to the evolution of CD4+ cell count and HIV RNA viral load in response to treatment of HIV infection. Statistics in Medicine, 24, 65–82.

Hsieh, F., Tseng, Y. K., & Wang, J. L. (2006). Joint modeling of survival and longitudinal data: Likelihood approach revisited. Biometrics, 62, 1037–1043.

Elashoff, R. M., Li, G., & Li, N. (2007). An approach to joint analysis of longitudinal measurements and competing risks failure time data. Statistics in Medicine, 26, 2813–2835.

Diggle, P. J., Sousa, I., & Chetwynd, A. G. (2008). Joint modelling of repeated measurements and time-to-event outcomes: The fourth Armitage lecture. Statistics in Medicine, 27, 2981–2998.

Ye, W., Lin, X., & Taylor, J. (2008). Semiparametric modeling of longitudinal measurements and time-to-event data—a two stage regression calibration approach. Biometrics, 84, 1238–1246.

Li, L., Hu, B., & Greene, T. (2009). A semiparametric joint model for longitudinal and survival data with application to hemodialysis study. Biometrics, 65, 737–745.

Liang, Y., Lu, W., & Ying, Z. (2009). Joint modeling and analysis of longitudinal data with informative observation times. Biometrics, 65, 377–384.

Liu, L. (2009). Joint modeling longitudinal semi-continuous data and survival, with application to longitudinal medical cost data. Statistics in Medicine, 28, 972–986.

DeGruttola, V., & Tu, X. M. (1994). Modeling progression of CD-4 lymphocyte count and its relationship to survival time. Biometrics, 50, 1003–1014.

Little, R. J. A. (1995). Modeling the drop-out mechanism in repeated-measures studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90, 1112–1121.

Rizopoulos, D. (2010). JM: An R package for the joint modelling of longitudinal and time-to event data. Journal of Statistical Software, 35(9), 1–33.

Tsiatis, A. A., & Davidian, M. (2004). Joint modeling of longitudinal and time-to-event data: An overview. Statistica Sinica, 14, 809–834.

Tsiatis, A. A., DeGruttola, V., & Wulfsohn, M. S. (1995). Modeling the relationship of survival to longitudinal data measured with error. Applications to survival and CD4 counts in patients with AIDS. JASA, 90, 27–37.

Zeng, D., & Cai, J. (2005). Simultaneous modelling of survival and longitudinal data with an application to repeated quality of life measures. Lifetime Data Analysis, 11, 151–174.

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

van den Bent, M. J., Brandes, A. A., Taphoorn, M. J. B., et al. (2013). Adjuvant procarbazine, lomustine, and vincristine chemotherapy in newly diagnosed anaplastic oligodendroglioma: Long-term follow-up of EORTC brain tumor group study 26951. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 344–350.

Aaronson, N. K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., et al. (1993). The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85, 365–376.

Osoba, D., Aaronson, N. K., Muller, M., et al. (1996). The development and psychometric validation of a brain cancer quality-of-life questionnaire for use in combination with general cancer-specific questionnaires. Quality of Life Research, 5, 139–150.

Bottomley, A., Vanvoorden, V., Flechtner, H., et al. (2003). The challenge and achievements of implementation of quality of life research in cancer clinical trials. European Journal of Cancer, 39, 275–285.

Cull, A., Sprangers, M., Bjordal, K., et al. (2002). Guidelines for translating EORTC questionnaires. Brussels: Quality of Life Group Publications, EORTC Publications.

Osoba, D., Rodrigues, G., Myles, J., et al. (1998). Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16, 139–144.

de Boor, C. (2001). A practical guide to splines, vol. 27 of springer series in applied mathematics (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Taphoorn, M. J. B., van den Bent, M. J., Mauer, M. E., et al. (2007). Health-related quality of life in patients treated for anaplastic oligodendroglioma with adjuvant chemotherapy: Results of a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 5723–5730.

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6, 239–472.

Rizopoulos, D., Verbeke, G., & Molenberghs, G. (2010). Multiple-imputation-based residuals and diagnostic plots for joint models of longitudinal and survival outcomes. Biometrics, 66, 20–29.

Viviani, S., Rizopoulos, D., & Alfo, M. (2014). Local sensitivity of shared parameter models to non-ignorability of dropout. Statistical Modelling, 14, 205–228.

R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/

SAS Institute Inc. (2011). SAS ® 9.3 system options: Reference (2nd ed.). Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Horowitz, J. L. (1999). Semiparametric estimation of a proportional hazard model with unobserved heterogeneity. Econometrica, 67, 1001–1028.

Abbring, J. H., & Van den Berg, G. J. (2007). The unobserved heterogeneity distribution in duration analysis. Biometrika, 94, 87–99.

Sweeting, M. J., & Thompson, S. G. (2011). Joint modelling of longitudinal and time-to-event data with application to predicting abdominal aortic aneurysm growth and rupture. Biometrical Journal, 53, 750–763.

Chen, L. M., Ibrahim, J. G., & Chu, H. (2011). Sample size and power determination in joint modeling of longitudinal and survival data. Statistics in Medicine, 2011(30), 2295–2309.

Rizopoulos, D., Murawska, M., Andrinopoulou, E. R., Molenberghs, G., Takkenberg, J. J. M., & Lesaffre, E. (2013). Dynamic predictions with time-dependent covariates in survival analysis using joint modeling and land marking. arXiv:1306.6479v1.

Ediebah, D. E., Coens, C., Maringwa, J. T., et al. (2013). Effect of completion-time windows in the analysis of health-related quality of life outcomes in cancer patients. Annals of Oncology, 24, 231–237.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the EORTC Brain Tumor Group, especially the principal investigator Prof. Dr Martin J. van den Bent and the other investigators and all patients who participated in this closed EORTC trial; and Cheryl Whittaker for editorial help. This study was supported by grants from the Belgian Cancer Foundation and USA Grant No. 5U10 CA011488-39 through 5U10 CA011488-40 from National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD), European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Charitable Trust, Belgian Cancer Foundation and Pfizer Global Partnership Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Formula for model 1

where \(h_{i} (t)\) denotes the hazard for an event for a patient i at time t, \(h_{0} (t)\) denotes the baseline hazard, and \(\omega_{i1} , \ldots ,\omega_{ip}\) is a set of covariates.

Formula for model 2

where \(N_{i} (t)\) is the counting process which counts the number of events for patient i by time t, \(h_{i} (t)\) denotes the intensity process for \(N_{i} (t)\), \(R_{i} (t)\) denotes the risk process (‘1’ if patient i still at risk at t), and \(y_{i} (t)\) denotes the value of the time-dependent covariate at t.

Formula for model 3

Survival submodel

where \(M_{i} (t) = \left\{ {m_{i} (s),\;0 \le s < t} \right\}\) denotes the history of the true unobserved longitudinal HRQoL score up to time t, \(h_{0} ( \cdot )\) denotes the baseline risk function, \(\alpha\) quantifies the effect of HRQoL score on the hazard for death, \(\omega_{i}\) baseline covariates.

Linear mixed-effect submodel

where \(\left\{ {B_{n} \left( {t,\lambda_{k} } \right);k = 1,2,3} \right\}\) denotes a B-splines basis matrix for a natural cubic splines of time 3 knots placed at equally spaced percentiles of the follow-up times, TTRT is the dummy variable for treatment. Age, WHO, PRES, and COSUR are the baseline covariates. \(b_{i}\) is the random-effects part, \(b_{i} \sim N(0, D)\), \(\varepsilon_{i} (t)\) is the measurement error term which is assumed independent of \(b_{i}\) with variance \(\sigma^{2}\).

Joint distribution

where b i is a vector of random effects that explains the interdependencies, \(p( \cdot )\) is the density function, and \(S( \cdot )\) is the survival function.

Dynamic predictions

and we are interested in

where \(u > t, \theta^{*}\) denotes the true parameter values and \(D_{n}\) denotes the sample the joint model was fitted.

SAS and R code to fit Cox models and joint models

Description: The SAS codes illustrate basic extended Cox models. The R script illustrates the basic use of the R package JM for fitting joint models for longitudinal and survival data.

-

The EORTC 26951 dataset

-

# AP score = longitudinal marker

-

# SS = Survival times

-

# TSS = Survival status

-

# TRTT = Randomized treatment

-

# QOLTIMES = AP score measurement times

-

#Baseline covariates: Age (>40 or ≤40), WHO (WHO performance status 0 or 1 vs. 2), PRES (prior surgery for a low-grade oligodendroglioma; yes or no), and COSUR (surgery; biopsy only vs. debulking surgery/resection).

SAS codes

Basic Cox model (model 1)

Time-dependent Cox model (model 2)

R script

The joint model: jointModel() takes the above fitted models as arguments and fits the joint model; below, we fit a joint model with a relative risk submodel for the event time outcome, in which the baseline risk function is assumed piecewise constant

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ediebah, D.E., Galindo-Garre, F., Uitdehaag, B.M.J. et al. Joint modeling of longitudinal health-related quality of life data and survival. Qual Life Res 24, 795–804 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0821-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0821-6