Abstract

Purpose

DIF detection within an IRT framework is highly powerful, often identifying significant DIF that is of little clinical importance. This paper introduces two metrics for IRT DIF evaluation that can discern potentially problematic DIF among items flagged with statistically significant DIF.

Methods

Computation of two DIF metrics—(1) a weighted area between the expected score curves (wABC) and (2) a difference in expected a posteriori scores across item response categories (dEAP)—is described. Their use is demonstrated using data from a 27-item cancer stigma index fielded to four adult samples: (1) Arabic (N = 633) and (2) English speakers (N = 324) residing in Jordan and Egypt, and (3) English (N = 500) and (4) Mandarin speakers (N = 500) residing in China. We used IRTPRO’s DIF module to calculate IRT-based Wald chi-square DIF statistics according to language within each region. After standard p value adjustments for multiple comparisons, we further evaluated DIF impact with wABC and dEAP.

Results

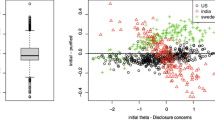

There were a total of twenty statistically significant DIF comparisons after p value adjustment. The wABCs for these items ranged from 0.13 to 0.90. Upon inspection of curves, DIF comparisons with wABCs >0.3 were deemed potentially problematic and were considered further for removal. The dEAP metric was also informative regarding impact of DIF on expected scores, but less consistently useful for narrowing down potentially problematic items.

Conclusions

The calculations of wABC and dEAP function as DIF effect size indicators. Use of these metrics can substantially augment IRT DIF evaluation by discerning truly problematic DIF items among those with statistically significant DIF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As an estimate of the posterior distribution, the group-specific EAPs used to compute the dEAP are well known to be biased toward the mean of underlying population distribution (see [36]). While in tests containing many items this bias is relatively small, in tests of fewer items the bias is more apparent.

References

Holland, P. W., & Wainer, H. (1993). Differential item functioning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Edelen, M. O., Thissen, D., Teresi, J. A., Kleinman, M., & Ocepek-Welikson, K. (2006). Identification of differential item functioning using item response theory and the likelihood-based model comparison approach: Application to the Mini-Mental State Examination [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Review]. Medical Care, 44(11 Suppl 3), S134–S142. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000245251.83359.8c.

Kim, J., Chung, H., Amtmann, D., Revicki, D. A., & Cook, K. F. (2013). Measurement invariance of the PROMIS pain interference item bank across community and clinical samples. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 22(3), 501–507. doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0191-x.

Orlando, M., & Marshall, G. N. (2002). Differential item functioning in a Spanish translation of the PTSD checklist: Detection and evaluation of impact. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Psychological Assessment, 14(1), 50–59.

Rose, J. S., Lee, C. T., Selya, A. S., & Dierker, L. C. (2012). DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence criteria characteristics for recent onset adolescent drinkers. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.]. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 124(1–2), 88–94. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.013.

Weisscher, N., Glas, C. A., Vermeulen, M., & De Haan, R. J. (2010). The use of an item response theory-based disability item bank across diseases: Accounting for differential item functioning. [Multicenter Study]. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(5), 543–549. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.07.016.

Carle, A. C., Cella, D., Cai, L., Choi, S. W., Crane, P. K., Curtis, S. M., et al. (2011). Advancing PROMIS’s methodology: Results of the third patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS((R))) Psychometric Summit. [Congresses Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 11(6), 677–684. doi:10.1586/erp.11.74.

Cook, K. F., Bamer, A. M., Amtmann, D., Molton, I. R., & Jensen, M. P. (2012). Six patient-reported outcome measurement information system short form measures have negligible age- or diagnosis-related differential item functioning in individuals with disabilities. [Comparative Study Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, Non-P.H.S.]. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(7), 1289–1291. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2011.11.022.

DeWitt, E. M., Stucky, B. D., Thissen, D., Irwin, D. E., Langer, M., Varni, J. W., et al. (2011). Construction of the eight-item patient-reported outcomes measurement information system pediatric physical function scales: built using item response theory. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Validation Studies]. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(7), 794–804. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.012.

Hahn, E. A., Devellis, R. F., Bode, R. K., Garcia, S. F., Castel, L. D., Eisen, S. V., et al. (2010). Measuring social health in the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): item bank development and testing. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Validation Studies]. Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 19(7), 1035–1044. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9654-0.

Petersen, M. A., Giesinger, J. M., Holzner, B., Arraras, J. I., Conroy, T., Gamper, E. M., et al. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the EORTC computerized adaptive test (CAT) fatigue item pool. Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation,. doi:10.1007/s11136-013-0372-2.

Smith, A. B., Armes, J., Richardson, A., & Stark, D. P. (2013). Psychological distress in cancer survivors: the further development of an item bank. Psycho-oncology, 22(2), 308–314. doi:10.1002/pon.2090.

Varni, J. W., Stucky, B. D., Thissen, D., Dewitt, E. M., Irwin, D. E., Lai, J. S., et al. (2010). PROMIS Pediatric Pain Interference Scale: An item response theory analysis of the pediatric pain item bank [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. The Journal of Pain: Official Journal of the American Pain Society, 11(11), 1109–1119. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.005.

Yeatts, K. B., Stucky, B., Thissen, D., Irwin, D., Varni, J. W., DeWitt, E. M., et al. (2010). Construction of the Pediatric Asthma Impact Scale (PAIS) for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). The Journal of Asthma : Official Journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma, 47(3), 295–302. doi:10.3109/02770900903426997.

Dorans, N. J., & Kulick, E. (2006). Differential item functioning on the Mini-Mental State Examination: An Application of the Mantel–Haenszel and standardization procedures [Review]. Medical Care, 44(11 Suppl 3), S107–S114. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000245182.36914.4a.

Miller, T. R., & Spray, J. A. (1993). Logistic discriminant function analysis for dif identification of polytomously scores items. Journal of Educational Measurement, 30(2), 107–122.

Swaminathan, H., & Rogers, H. (1990). Detecting differential item functioning using logistic regression procedures. Journal of Educational Measurement, 27, 361–370.

Meade, A. W., & Wright, N. A. (2012). Solving the measurement invariance anchor item problem in item response theory. The Journal of applied psychology, 97(5), 1016–1031. doi:10.1037/a0027934.

Woods, C. M. (2009). Empirical selection of anchors for tests of differential item functioning [article]. Applied Psychological Measurement, 33(1), 42–57. doi:10.1177/0146621607314044.

Thissen, D., Steinberg, L., & Wainer, H. (1993). Detection of differential item functioning using the parameters of item response models. In P. W. Holland & H. Wainer (Eds.), Differential item functioning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cai, L., du Toit, S., & Thissen, D. (2011). IRTPRO: Flexible, multidimensional, multiple categorical IRT modeling [Computer software] Chicago. IL: Scientific Software International. Inc.

Langer, M. M. (2008). A reexamination of Lord’s Wald test for differential item functioning using item response theory and modern error estimation. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina.

Lord, F. M. (1980). Applications of item response theory to practical testing problems. London: Routledge.

Cai, L. (2008). SEM of another flavour: Two new applications of the supplemented EM algorithm. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 61, 309–329. doi:10.1348/000711007x249603.

Meng, X. L., & Rubin, D. B. (1991). Using EM to obtain asymptotic variance: covariance matrices—the SEM algorithm. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 86(416), 899–909. doi:10.2307/2290503.

Irwin, D. E., Stucky, B., Langer, M. M., Thissen, D., DeWitt, E. M., Lai, J.-S., et al. (2010). An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Quality of Life Research, 19(4), 595–607.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300.

Thissen, D., Steinberg, L., & Kuang, D. (2002). Quick and easy implementation of the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling the false positive rate in multiple comparisons. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 27(1), 77–83.

Steinberg, L., & Thissen, D. (2006). Using effect sizes for research reporting: Examples using item response theory to analyze differential item functioning. Psychological Methods, 11(4), 402–415.

Raju, N. S., van der Linden, W. J., & Fleer, P. F. (1995). IRT-based internal measures of differential functioning of items and tests. Applied Psychological Measurement, 19(4), 353–368.

Samejima, F. (1997). Graded response model. In W. J. van der Linden & R. K. Hambleton (Eds.), Handbook of modern item response theory (pp. 85–100). New York: Springer.

Drasgow, F. (1987). Study of the measurement bias of two standardized psychological-tests. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(1), 19–29. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.72.1.19.

Oshima, T., Kushubar, S., Scott, J., & Raju, N. (2009). DFIT8 for window user’s manual: Differential functioning of items and tests. St. Paul, MN: Assessment Systems Corporation.

Chandra, A., Edelen, M., Orr, P., Stucky, B., & Schaefer, J. (2013). Developing a global cancer stigma index. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. (1998–2010). Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen.

Bock, R. D., & Mislevy, R. J. (1982). Adaptive EAP estimation of ability in a microcomputer environment. Applied Psychological Measurement, 6(4), 431–444.

Acknowledgments

The cancer stigma index development described in this article was funded by the LIVESTRONG Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Edelen, M.O., Stucky, B.D. & Chandra, A. Quantifying ‘problematic’ DIF within an IRT framework: application to a cancer stigma index. Qual Life Res 24, 95–103 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0540-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0540-4