Abstract

Background

Depression is common in patients with cardiac disease; however, the use of depression-specific health instruments is limited by their increased responder and analyst burden. The study aimed to define a threshold value on the Short Form-36 (SF-36) mental component summary score (MCS) that identified depressed cardiac patients as measured by the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D).

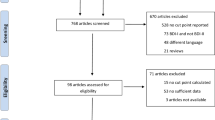

Methods

An optimal threshold was determined using receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves on SF-36 and CES-D data from a large cardiac cohort (N = 1,221). The performance of this threshold was evaluated in a further two cardiac populations.

Results

In the index cohort, an SF-36 MCS score of ≤45 was revealed as an optimal threshold according to maximal Youden Index, with high sensitivity (77%, 95% CI = 74–80%) and specificity (73%, 95% CI = 69–77%). At this threshold, in a second sample of hospital cardiac patients, sensitivity was 93% (95% CI = 76–99%) and specificity was 64% (95% CI = 49–77%). In a final sample generated from a community population, specificity was 100% (95% CI = 85–100%) and sensitivity was 68% (95% CI = 61–74%) at the cut-off of 45.

Conclusion

The SF-36 MCS may be a useful research tool to aid in the classification of cardiac patients according to the presence or absence of depressive symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CES-D:

-

Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- HT/Chol:

-

Hypertension and/or high cholesterol

- IDACC:

-

Identifying depression as a comorbid condition

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- NWAHS:

-

North West Adelaide Health Service

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- ROC:

-

Receiver-operating characteristic

- SF-36:

-

Short-Form 36

- SF-36 MCS:

-

Short-Form 36 mental summary score

- SF-36 PCS:

-

Short-Form 36 physical summary score

References

Penninx, B. W., et al. (2001). Depression and cardiac mortality: Results from a community-based longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58(3), 221–227.

Wulsin, L. R., & Singal, B. M. (2003). Do depressive symptoms increase the risk for the onset of coronary disease? A systematic quantitative review. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(2), 201–210.

Glassman, A. H., et al. (2002). Sertraline treatment of major depression in patients with acute MI or unstable angina. JAMA, 288(6), 701–709.

Berkman, L. F., et al. (2003). Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: The Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. JAMA, 289(23), 3106–3116.

Schrader, G., et al. (2005). Effect of psychiatry liaison with general practitioners on depression severity in recently hospitalised cardiac patients: A randomised controlled trial. Medical Journal of Australia, 182(6), 272–276.

McDowell, I., & Newell, C. (1996). Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires (p. 523). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kavan, M. G., et al. (1990). Screening for depression: Use of patient questionnaires. American Family Physician, 41(3), 897–904.

Attkisson, C. C., & Zich, J. M. (1990). Depression in primary care. National institute of mental health (U.S.), University of California San Francisco. New York: Routledge.

Weissman, M. M., et al. (1977). Assessing depressive symptoms in five psychiatric populations: A validation study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 106(3), 203–214.

Roberts, R. E., & Vernon, S. W. (1983). The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: Its use in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140(1), 41–46.

Schulberg, H. C., et al. (1985). Assessing depression in primary medical and psychiatric practices. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42(12), 1164–1170.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Spertus, J. A., et al. (2002). Health status predicts long-term outcome in outpatients with coronary disease. Circulation, 106(1), 43–49.

Dougherty, C. M., et al. (1998). Comparison of three quality of life instruments in stable angina pectoris: Seattle Angina Questionnaire, Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), and Quality of Life Index-Cardiac Version III. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(7), 569–575.

Smith, H. J., Taylor, R., & Mitchell, A. (2000). A comparison of four quality of life instruments in cardiac patients: SF-36, QLI, QLMI, and SEIQoL. Heart, 84(4), 390–394.

Ware, J. E., Jr., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1994). SF-36 Physical, mental health summary scales: A user’s manual. Boston, Massachusettsd: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center.

Ware, J. E., Jr., & Gandek, B. (1998). Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the international quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 903–912.

McCallum, J. (1995). The SF-36 in an Australian sample: Validating a new, generic health status measure. Australian Journal of Public Health, 19(2), 160–166.

Failde, I., & Ramos, I. (2000). Validity and reliability of the SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire in patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(4), 359–365.

Permanyer-Miralda, G., et al. (1991). Comparison of perceived health status and conventional functional evaluation in stable patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 44(8), 779–786.

Berwick, D. M., et al. (1991). Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care, 29(2), 169–176.

Failde, I., Ramos, I., & Fernandez-Palacin, F. (2000). Comparison between the GHQ-28 and SF-36 (MH 1–5) for the assessment of the mental health in patients with ischaemic heart disease. European Journal of Epidemiology, 16(4), 311–316.

McHorney, C. A., Ware, J. E., Jr., & Raczek, A. E. (1993). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care, 31(3), 247–263.

Ware, J. E., Jr., et al. (1995). Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: Summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Medical Care, 33(4 Suppl), AS264–AS279.

Wells, K. B., et al. (1989). The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA, 262(7), 914–919.

Mancuso, C. A., Peterson, M. G., & Charlson, M. E. (2000). Effects of depressive symptoms on health-related quality of life in asthma patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 15(5), 301–310.

Elliott, T. E., Renier, C. M., & Palcher, J. A. (2003). Chronic pain, depression, and quality of life: Correlations and predictive value of the SF-36. Pain Medicine, 4(4), 331–339.

Cheok, F., et al. (2003). Identification, course, and treatment of depression after admission for a cardiac condition: Rationale and patient characteristics for the Identifying Depression As a Comorbid Condition (IDACC) project. American Heart Journal, 146(6), 978–984.

Grant, J. F., et al. (2006) The North West Adelaide Health study: Detailed methods and baseline segmentation of a cohort for selected chronic diseases. Epidemiologic Perspectives Innovations 3(4).

Grant, J.F., et al. (2008). Cohort profile: The North West Adelaide Health study (NWAHS). International Journal of Epidemiology.

Bergmann, M. M., et al. (1998). Validity of self-reported diagnoses leading to hospitalization: A comparison of self-reports with hospital records in a prospective study of American adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 147(10), 969–977.

Heckbert, S. R., et al. (2004). Comparison of self-report, hospital discharge codes, and adjudication of cardiovascular events in the Women’s Health Initiative. American Journal of Epidemiology, 160(12), 1152–1158.

Okura, Y., et al. (2004). Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 57(10), 1096–1103.

Ensel, W. (1986) Measuring depression: The CESD scale, in social support, life events and depression. In Lin, N., Dean, A., Ensel, W. M. (Eds.). Academic Press: New York.

Zich, J. M., Attkisson, C. C., & Greenfield, T. K. (1990). Screening for depression in primary care clinics: The CES-D and the BDI. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 20(3), 259–277.

ABS. (2003). Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas, Australia, 2001. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Youden, W. J. (1950). Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer, 3(1), 32–35.

Walsh, T. L., et al. (2006). Screening for depressive symptoms in patients with chronic spinal pain using the SF-36 Health Survey. Spine J, 6(3), 316–320.

Schatzkin, A., et al. (1987). Comparing new and old screening tests when a reference procedure cannot be performed on all screenees. Example of automated cytometry for early detection of cervical cancer. American Journal of Epidemiology, 125(4), 672–678.

Fluss, R., Faraggi, D., & Reiser, B. (2005). Estimation of the Youden index and its associate cutoff point. Biometric Journal, 47(4), 458–472.

Schisterman, E. F., et al. (2001). TBARS and cardiovascular disease in a population-based sample. Journal of Cardiovascular Risk, 8(4), 219–225.

Stafford, L., Berk, M., & Jackson, H. J. (2007). Validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale and patient health questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with coronary artery disease. General Hospital Psychiatry, 29(5), 417–424.

Strik, J. J., et al. (2001). Sensitivity and specificity of observer and self-report questionnaires in major and minor depression following myocardial infarction. Psychosomatics, 42(5), 423–428.

Lowe, B., et al. (2004). Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: Sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Journal of Affective Disorders, 81(1), 61–66.

Oliver, J., & Simmons, M. (1984). Depression as measured by the DSM-III and the beck depression inventory in an unselected adult population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 52(5), 892–898.

Parikh, R. M., et al. (1988). The sensitivity and specificity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in screening for post-stroke depression. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 18(2), 169–181.

Gerety, M. B., et al. (1994). Performance of case-finding tools for depression in the nursing home: Influence of clinical and functional characteristics and selection of optimal threshold scores. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 42(10), 1103–1109.

Okimoto, J. T., et al. (1982). Screening for depression in geriatric medical patients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 139(6), 799–802.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tavella, R., Air, T., Tucker, G. et al. Using the Short Form-36 mental summary score as an indicator of depressive symptoms in patients with coronary heart disease. Qual Life Res 19, 1105–1113 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9671-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9671-z