Abstract

In this article, we examine the methodological writings of James M. Buchanan and relate them to those of the moral philosopher, Martin Buber. We analyze Buchanan’s views, both explicit and implicit in his writings, on the morality of the exchange relationship between individuals. We imagine a hypothetical meeting between Buchanan and Buber and conclude that Buchanan would have agreed with Buber’s dialogical philosophy of human interaction as a foundation for his catallactic point of view.

Similar content being viewed by others

My mother took her knitting needles and a ball of wool and improbably turned it all into a sweater. Fantastic! And I found out the secret of it holding together was the combination of warp and woof, the process in which one thread goes under the other, then over the other, then under the other, and so on, until it all just holds up…. In the same way, human beings depend on each other – without mutual support, none of us could exist…. We live in the midst of a woven tapestry [of] the warps and woofs…. If you didn’t have one, you wouldn’t have the other, because it takes two to reveal the pattern. We are patterns in a weaving system. We wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for the interlocking of all these different spectra of dimensions (Watts, 2017, p. 43).

1 Introduction

As Alan Watts points out in the quote we have chosen for our epigraph, human beings depend upon a system of mutual support for their very existence. From the interlocking warps and woofs of human interaction and exchange emerge the tapestries of complex human social systems. An economy is perhaps the prime example of such a complex interacting system that is based upon mutuality, reciprocity, and exchange in the broadest sense – not just of goods and services but of culture, language, and ideas. James Buchanan stands out amongst his peers as one who wrote most clearly and powerfully about economics as exchange. Buchanan conceived of the domain of economics as follows:

The subjective elements of our discipline are defined precisely within the boundaries between the positive, predictive science of the orthodox model on the one hand and the speculative thinking of moral philosophy on the other. (Buchanan, 1982, p. 8)

In this article we highlight one of the most underappreciated aspects of Buchanan’s scholarship – the moral and creative foundations of the discipline. Keeping the subjective domain in mind when doing economics can help avoid the intellectual confusion of scientism and an extreme objectification of human beings that leads to a truly inhuman social science. We proceed by comparing Buchanan’s conception of the moral and creative foundations of economics with those of the moral philosopher Martin Buber. Buber’s existential philosophy serves to draw out and give emphasis to Buchanan’s conception of economics as moral exchange. In that comparison, a clear picture emerges regarding how and why Buchanan thought economics needed a moral-creative foundation. A clear understanding of that groundwork is essential for economists to cut through the intellectual haze of some of the most difficult problems in our discipline.

This paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we review Buchanan’s writings on methodology, specifically his ideas on the spontaneous coordination of markets and on the transactional relationship between individuals who engage in exchange. In Sect. 3, we examine briefly Martin Buber’s moral philosophy and his concepts of two-word pairs. They are the I-It and the I-Thou. In Sect. 4, we frame the discussion in the context of the Crusoe Economy as usually cited in introductory textbooks. In Sect. 5, we conclude.

2 Buchanan on catallactics and symbiotics

In his writings on methodology, Buchanan pleaded with his fellow economists to consider as the central issue of the discipline the study of the transactional relationship between economic actors engaging in exchange. In his most famous paper on the topic, Buchanan quotes the founder of the discipline, Adam Smith, in noting, “… a certain propensity in human nature to truck, barter, and exchange… (Buchanan, 1964, p. 213). In answering the question, “What should economists do,” Buchanan puts forward a “theory of markets” and claims:

Economists should concentrate their attention on a particular form of human activity, and upon the various institutional arrangements that arise as a result of this form of activity. Man’s behavior in the market relationship, reflecting the propensity to truck and to barter, and the manifold variations in structure that this relationship can take; these are the proper subjects for the economist’s study. (Buchanan, 1964, p. 214)

For Buchanan, economics is about more than the efficient allocation of resources (“economizing”), and the appropriate methodology for economic theory is deeper than mere “computation” (Buchanan, 1964, p. 216) or the “maximization of objective functions subject to constraints” (Buchanan, 1979, p. 81). He states further that “the maximization paradigm is the fatal methodological flaw in modern economics” (Buchanan, 1979, p. 281). Buchanan would have economists focus instead on Smithian trucking and bartering. It is human’s unique propensity that creates value and leads to mutually beneficial outcomes between agents. He writes that “I want them [economists] to concentrate on exchange rather than on choice” (Buchanan, 1964, p. 217).

Buchanan mentions that he considered titling the postscript to his book on economic methodology, “Why I am not an economist” (Buchanan, 1979, p. 279). Apparently, he felt that it might be too late to turn the tide of association of the term “economics” with the methodology of constrained maximization. In its place he suggests:

Should I have my say, I should propose that we cease, forthwith, to talk about economics or political economy…. Were it possible to wipe the slate clean, I should recommend that we take up a wholly different term such as catallactics, or symbiotics.

Both Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek used the term catallactics in their writings. Hayek proposed the word derived from the Greek root katallasso, which has the meanings: “to exchange”, “to admit in the community”, and “to change from enemy into friend” (Hayek, 1976, pp. 108–109). For Buchanan, catallactics is preferred to the word economics owing to the former’s focus on exchange.

Buchanan favored the term symbiotics because it connotes that the “association is mutually beneficial to all parties” (Buchanan, 1964, p. 217). Symbiosis, he wrote, is the heart of economics because it highlights the cooperative “association of individuals, one with another” (Buchanan, 1964, p. 217). Interdependence is the single most important aspect of economics for Buchanan and is located in the subjectivity of “active choice” (Buchanan, 1982, p. 9). It is transactional and is brought about by voluntary means.

It is essential to understand what Buchanan refers to as “subjective active choice” of individuals in a symbiotic relationship. The inception of economic exchange is rooted in this uniquely human behavior, which is emergent, creative, entrepreneurial, and, therefore, unpredictable. As the most essential aspect of economics, exchange could not have evolved in the setting of the equilibrium models of mathematical economics, in which agents optimize objective functions subject to constraints. In such equilibrium settings, agents respond only passively to stimuli, and thus could not spontaneously organize through exchange institutions in the first place.Footnote 1 It is such “active choice” that Buchanan refers to as “arbitrage” or “entrepreneurship” (Buchanan, 1979, p. 281). Note that Buchanan’s arbitrage is not the perfect and zero-sum arbitrage of modern financial economics that is, by definition, risk free. Instead, it is an arbitrage that creates opportunities for others and thereby leads to positive-sum outcomes. To summarize that point, Buchanan writes:

Mutual gains can be secured through cooperative endeavor, that is, through exchange or trade. This mutuality of advantage that may be secured by different organisms as a result of cooperative arrangements, be these simple or complex, is the one important truth in our discipline. (Buchanan, 1964, p. 218; emphasis added)

Buchanan was wary of the dominant methodology of utility optimization in mathematical economics, thinking that it would lead to a paradigm of economists as “social engineers” instead of conveyors of this “one important truth” (Buchanan, 1964, p. 216). He strongly resisted the trend of objectification in economic theory. It is only the passive element of economic behavior that is amenable to mathematical treatment, and thus he saw the trend of mathematization in economic theory as perverse and “productive of intellectual muddle” (Buchanan, 1964, p. 218). Harm does not arise from the use of mathematics per se, but rather from focusing exclusively on the predictable element of behavior that alone could never have given rise to the institutions of exchange. It is the exchange relationship that is, and should be viewed as, the most central aspect of the discipline. He states that in the maximization paradigm:

The market becomes an engineered construction, a mechanism, an analogue calculating machine, a computational device, one that processes information, accepts inputs, and transforms these into outputs which it then distributes. (Buchanan, 1964, p. 219)

Buchanan rejects the teleological view embedded in this paradigm, in which the market “solves” the “economic problem”, and results, under ideal circumstances, in the efficient allocation of resources. Although the objective view of the market institution is amenable to mathematical modeling, it obscures the emergence of the exchange relationship itself. Economists should instead study the bottom-up, emergent process of mutually beneficial exchange that results from the subjective propensity to truck and barter and create value for others. Indeed, on this point Buchanan is unyielding:

The market or market organization is not a means toward the accomplishment of anything. It is, instead, the institutional embodiment of the voluntary exchange processes that are entered into by individuals in their several capacities. This is all there is to it. (Buchanan, 1964, p. 219)

The proper domain of the discipline of economics does not belong wholly to the field of moral philosophy. Instead, it exists as a nexus between the subjective elements of moral philosophy and the objective elements of predictive science. He cites economic experiments conducted on rats that find basic agreement with the objective theory of utility maximization (Kagel et al., 1981). For Buchanan, those laboratory results do point to a discipline of genuine predictive science. Thus, he claims that “There is surely room for both sciences to exist in the more inclusive rubric that we call economic theory” (Buchanan, 1982, p. 217). But again, for Buchanan, the primary, most essential economic concept is that markets achieve spontaneous order through the process of voluntary exchange.

2.1 Knightian reciprocity and mutuality

Throughout his career, James Buchanan insisted on a position of methodological individualism as the basis for any sound economic reasoning and modeling. For Buchanan, any concept of the organic collective or of coercive collective decision making was simply outside the scope of economics. Economics is, by definition, the study of voluntary exchange, and as we noted above, he shared with Hayek a dissatisfaction with the word “economics” because of its Greek root meaning “household management”. Catallactics or symbiotics, by contrast, highlight the roots of the discipline in voluntary exchange.

One sees the very strong influences of Hayek and Knight upon Buchanan in the foregoing strands of his thought. In his essay From the Inside Looking Out, Buchanan quotes at length his mentor and Professor Frank Knight:

It is intellectually impossible to believe that the individual can have any influence to speak of …on the course of history. But it seems to me that to regard this as an ethical difficulty involves a complete misconception of the social-moral problem.… I find it impossible to give meaning to an ethical obligation on the part of the individual to improve society.

The disposition of an individual, under liberalism, to take upon himself such a responsibility seems to be an exhibition of intellectual and moral conceit …; it is unethical. Ethical-social change must come about through a genuine moral consensus among individuals meeting on a level of genuine equality and mutuality and not with anyone in the role of cause and the rest in that of effect, of one the “potter” and the others as “clay.” (Buchanan, 1992, p. 148).

Commenting on the quotation from his mentor, Buchanan cautions the reader not to misunderstand:

He is not advancing a logic of rationally grounded abstention from discussion about changes in the rules for social order. He is defining the limits or constraints under which any individual must place himself as he enters into such discussion. The moral conceit that bothers Knight arises when any individual, or group, presumes to take on the responsibility for others, independently of their expressed agreement in a setting of mutuality and reciprocity. The underlying principle is indeed a simple one: Each person counts equally [emphasis added]. (Buchanan, 1992, pp. 148–149)

Knight indeed had a profound impact on Buchanan’s development as an economist. When asked to write about his “evolution as an economist”, Buchanan wrote:

I am not a “natural economist” as some of my colleagues are, and I did not “evolve” into an economist. Instead I sprang full-blown, upon intellectual conversion, after I “saw the light” … I was indeed converted by Frank Knight, but he almost single-mindedly conveyed the message that there exists no god whose pronouncements deserve elevation to the sacrosanct, be this god within or without the scientific academy. Everything, everyone, anywhere, anytime - all is open to challenge and criticism. There is a moral obligation to reach one’s own conclusions. (Buchanan, 1992, pp. 68–69)

It is not difficult to see an insistence on personal authority for one’s positions in Buchanan’s writings. Still, we argue that what might be called the Knightian moral-social, or ethical-social position is foundational in Buchanan’s thought. Commenting on that foundation, he writes:

Critics have charged that my work has been driven by an underlying normative purpose, and, by inference, if not directly, they have judged me to be mildly subversive. [But] anyone who models interaction structures that might be is likely to be accused of biasing analysis toward those alternatives that best meet his personal value standards. Whether or not my efforts have exhibited bias in this sense is for others to determine. I shall acknowledge that I work always within a self-imposed constraint that some may choose to call a normative one. I have no interest in structures of social interaction that are nonindividualist in the potter-clay analogy mentioned in the earlier citation from Frank Knight. That is to say, I do not extend my own analysis to alternatives that embody the rule of any person or group of persons over other persons or group of persons. If this places my work in some stigmatized normative category, so be it. (Buchanan, 1992, p. 152; emphasis added)

We argue that such a Knightian moral-social position is foundational to the intellectual world of James Buchanan. It is self-evident in his scholarship that he followed his mentor’s insistence that one work out one’s positions for oneself. We thus conclude that Buchanan indeed held this position firmly.

2.2 The market as a creative process

One additional element of Buchanan’s catallactic point of viewFootnote 2 deserves mention. Buchanan (1999) gives a short, but powerful statement of his view of the market as a creative process wherein order emerges endogenously from genuine subjective choice. That statement is related to other statements in which he distinguishes between reactive choice and truly creative choice (Buchanan, 1982, p.9). It is only in the latter that a modern society can locate its necessary dynamism to coordinate the ever more complex and constantly shifting plans of individuals. Indeed, he states:

[T]he “order” of the market emerges only from the process of voluntary exchange among the participating individuals. The “order” is, itself, defined as the outcome of the process that generates it. The “it,” the allocation-distribution result, does not, and cannot, exist independently of the trading process. Absent this process, there is and can be no “order.” (Buchanan, 1999, p. 244).

And commenting on the neoclassical view of the utility-maximizing automaton, he further states:

[I]n this presumed setting, there is no genuine choice behavior on the part of anyone. This…is misleading. Individuals do not act so as to maximize utilities described in independently-existing functions. They confront genuine choices.… (Buchanan, 1999, pp. 244–245).

In a lecture titled Natural and Artifactual Man (Buchanan, 1979, pp. 93–112), Buchanan distinguishes between modes of human nature that parallel his concepts of reactive choice and creative choice. The natural man is the man of reactive choice, while what he calls the artifactual man is the man of truly creative choice. Once again citing the studies conducted on rats, he agrees that there is a natural-reactive element to man that is amenable to scientific prediction. This is the microeconomic theory of standard textbooks. But again, it is the artifactual-creative aspect of man that has been almost entirely neglected in mainstream economic theory. He mentions the common examples of an individual deciding to lose weight by dieting or another individual who may decide to stop smoking as simple examples of human behavior that the received theory simply cannot explain. For Buchanan, the essence of the artifactual man is the sense of constructing oneself through purposeful action as the real-time process of life unfolds. Another aspect of the artifactual man is his ability to engage in counterfactual reasoning. His past choices may constrain his future opportunity set, but within those constraints he deliberately makes choices [in the creative sense] to become what he can envision himself to be. Because its sole domain is that of the natural man amenable to predictive analysis, neoclassical theory must be entirely silent on the most human aspects of life. He ends the essay with this strong statement:

Man wants liberty to become the man he wants to become. He does so precisely because he does not know what man he will want to be in time. Let us remove once and for all the instrumental defense of liberty, the only one that can possibly be derived directly from orthodox economic analysis. Man does not want liberty to maximize his utility, or that of the society of which he is a part. He wants liberty to become the man he wants to become. (Buchanan, 1979, p. 112).

In an essay titled Retrospect and Prospect, Buchanan makes what he calls a few “cryptic statements or assertions” meant to “challenge thought”. In the third of those cryptic statements, he writes:

Economics involves actors. Without actors, there is no play. This truism has been overlooked by modern economists whose universe is peopled with passive responders to stimuli…. How can entrepreneurship be modeled? Increasingly, I have come to the view that the role of entrepreneurship has been the most neglected area of economic inquiry, with significant normative implications for the general understanding of how the whole economy works. (Buchanan, 1979, pp. 280–281).

That passage very much aligns with Buchanan’s view of the artifactual man who engages in genuinely creative choice. But at this stage, we detect a divergence from his mentor, Frank Knight, who is perhaps most famous for his work on entrepreneurship. The Knightian entrepreneur plays a specialized role in the economy that he likened to biological cephalization (Knight, 2014, pp. 268–269). For Buchanan, the entrepreneurial spirit is universal. It is present in every human being. While the models of orthodox economics are populated with the automaton Homo economicus, the agents that peopled the models of James Buchanan were Homo sapiens.Footnote 3 The agents are fully human. They are flawed, fallible, subject to cognitive constraints and the full spectrum of human foibles; but also, and crucially, they are creative, dynamic, imaginative and entrepreneurial. A very strong case can be made that the only economic models in which Buchanan was interested were comprised of genuine human actors, which provides fertile ground for the intellectual meeting of Buchanan and Buber.

3 Buber’s worlds of it and thou

Martin Buber was an influential Jewish philosopher and thinker often associated with the existentialist philosophical tradition. He was born in Vienna in 1878 and died in 1965 in Israel. In 1923, he was appointed lecturer in Jewish Religious Philosophy and Ethics at the University of Frankfurt. After Hitler was elected as German Chancellor, Buber resigned his position and was banned from teaching. In 1938, he left Germany for British Palestine. After his emigration, Buber was appointed Chair of the Department of Sociology of Hebrew University. During his later career, Buber received many awards, including the Goethe Prize of the University of Hamburg [1951], the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade [1953], the first Israeli honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences [1961], and the Erasmus Prize [1963]. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature ten times and for the Nobel Peace Prize seven times (Scott, 2019, pp. 1–5).

Buber’s most famous work is the book titled I and Thou, in which he outlined his “dialogic” philosophy of human relations. In the introduction to the book, he writes of the “twofold attitude” and “twofold nature” of our most basic relationships in life (Buber, 1937, p. 3). It’s perhaps best to quote Buber directly on the matter:

To man the world is twofold, in accordance with his twofold attitude. The attitude of man is twofold, in accordance with the twofold nature of the primary words which he speaks. The primary words are not isolated words, but combined words. The one primary word is the combination I-Thou. The other primary word is the combination I-It…. Hence the I of man is twofold…. Primary words are spoken from the being. If Thou is said, the I of the combination I-Thou is said along with it. If It is said, the I of the combination I-It is said along with it. The primary word I-Thou can only be spoken with the whole being. The primary word I-It can never be spoken with the whole being. (Buber, 1937, p. 3)

Buber distinguishes between two different modes of existence. In doing so, he discusses two fundamental word pairs: I-It and I-Thou. He does not deny that more than those two binary classes of being are possible (especially for the complex state of the inner being), but he holds that when man acts outwardly, he engages in one of the two basic forms. The reality of being for Buber is relation. The I in each of the word pairings is defined in relationship to its pair: It and Thou. For Buber, the two basic forms of relation define the entirety of man’s outward behavior. The two basic word pairs that define relationships are present in three fundamental ways: first, man’s relationship to nature; second, man’s relationship to his fellow man; and third, man’s relationship to Spirit or God. Herein, we will focus exclusively on the second category. It is here that we imagine a meeting of the minds of James Buchanan and Martin Buber.

3.1 The world of it

In the I-It pairing, the relationship of the I is defined in terms of the It. It is a relationship that is all about experience, function, and objects. In each possible relation, the It represents an object that is something fully classified, wholly defined, completely circumscribed, and therefore limited and predictable, which, for Buber, defines the dominant form of man’s relationships to others. In each possible case, it is entirely possible that the It in the I-It word pairing could be replaced with he or she. That is, (and perhaps especially so in economics) it is entirely possible that the object the It relates to is another human being. In this world, others are regarded as means to an end; they are defined by their function and are seen as objects to either be used or experienced. This fundamental limitation implies that others are not seen as whole beings; they are fragmented. For Buber, the essential outcome of the objectification process is that the I that relates to the It likewise is fundamentally limited and fragmented. The I can never relate to the It with the wholeness of his or her being. One crucial aspect is that no creativity is found in this mode; there is no room for growth or development. It is a static state in which nothing new can emerge beyond the fixed boundaries and borders.

3.2 The world of thou

The second basic word pairing for Buber is that of I-Thou. As opposed to the I-It, the I-Thou mode of existence is focused on wholeness, humanity, mutuality, and authentic human relation. When an I relates to a Thou in the I-Thou mode, he or she does so in an open and active manner. In that way, the I develops into a whole and complete being through the transactional process of relating to the Thou. The I of the I-Thou pairing does not objectify an It, but rather stands in relation to another Thou in an open and dynamic dialogue. In that sense, Buber’s I-Thou orientation can be said to be transactional. It is through a process of encounter in which individuals meet each other in mutuality that our full humanity is made manifest. Each individual in the pairing simultaneously is giving of themselves while receiving the being of the other. It is truly creative in the sense that something new emerges in the process of giving and receiving. It is and expansionary process of moral exchange.

3.3 It and thou in language patterns

In the I-Thou mode of being, the relation is one of subject to subject, whereas in the I-It mode of being, the relation is one of subject to object. For Buber, the two pairs are not merely suggestive classifications, but ontological realities. He suggested that the two fundamental modes of relating can be detected readily in the way we use language. In particular, he calls us to pay careful attention to how we use the word I. Do we use the word I in relation to a mere object even if we use personal pronouns, or do we use the word I in relation to another subject? And for Buber, it doesn’t matter if the subject is non-human. For instance, he spoke about the possibility of an I-Thou relation with a tree. We present some linguistic examples below from Robinson Crusoe and from standard economics textbooks.

3.4 The temporal modalities of I-It and I-Thou

One especially important dimension of the two ways of relating is found in their temporal modalities. The temporality of the I-It perpetually remains in the past. The It is treated as a fixed set of patterns developed through habit over time. The I relates to the It in terms of such a fixed set of patterns and does not allow for change or dynamism. Even imagined future uses or experiences of It as an object must be extrapolated from experience. The It is held constant in time and space. It is limited, contained, bounded, and regular.

From that fixed state of regularity, it is possible to extrapolate into an imagined future. However, any imagined future scenarios originate in the fixed past not the dynamic unfolding present. It is like trying to capture a flowing river in a bucket. In the bucket, the river does not flow but is reduced to a volume of stagnant water.Footnote 4 One may imagine using the water in the future for drinking, bathing, or washing, but it is no longer the river that flows.

In that sense then, the phrase “stuck in the past” is not a metaphor but a profound reality. The I that is addressing the It in such a limiting way must be bound and limited in like manner. For Buber, I-It represents a perverse orientation towards time and the unfolding process of the universe. For him, each true entity is, in reality, flowing. Just as in the bucket the river cannot flow, so too the I contained in the fixed borders and boundaries of the It cannot become. There is nothing creative about the I-It. There is no exploration, only exploitation.

The temporality of the I-Thou, however, is ever in the spontaneously unfolding present. It is the fundamental source of creativity, novelty, and all authentic becoming. Taking a stand as an I to another as a Thou requires an openness to innumerable possibilities. In its crucial aspect, the I-Thou is essentially a dynamic mode of relation. For Buber, I-Thou was the source of all meaningful growth and development. All genuine growing and becoming require the presence of a Thou. By being open to the innumerable possibilities in others, one becomes open to innumerable paths of growth and development in oneself. In the unpredictable flux of open and authentic relation, Buber saw the source of all creative activity and spiritual development.

4 James Buchanan meets Martin Buber

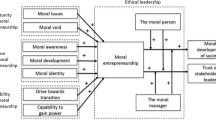

To facilitate the comparison of Buchanan’s economics and Buber’s philosophy, we present the following outline in tabular form. The outline will serve as a side-by-side comparison of Buchanan’s approach to economics versus the mainstream approach organized according to Buber’s modes of relation. In the following section we develop the comparison (Table 1).

We previously have compared Buchanan’s catallactics with the orthodox model of allocative efficiency, but we can now add to the discussion the I-It and I-Thou modes of relation as a means of distinguishing between the two. As we will see, the comparison provides a deeply insightful interpretation of Buchanan’s economics.

As we pointed out earlier, Buchanan rejected the allocative-distributive model of market dynamics in favor of a catallactic-symbiotic paradigm. But what is it about the orthodox model for Buchanan that is most objectionable? He explains as follows:

Its flaw lies in its conversion of individual choice behavior from a social-institutional context to a physical-computational one. [S]urely this is nonsensical social science…. (Buchanan, 1979, p. 29)

The most offensive aspect of the standard model is that it objectifies the individual agent. It turns attention away from the very human process of mutually beneficial exchange to one of rote computation – the kind a mere machine could do. While he does not adopt Buber’s precise language, Buchanan comes close to saying that the basic difference is between an I-It and an I-Thou way of relating. The I-It corresponds to the allocative-distributive model, in which the agent is a mere computational cog in a machine. The I-Thou corresponds to Buchanan’s symbiotics, in which actual creative humans (capable of artifactual reasoning) encounter opportunities for exchange on grounds of mutuality and reciprocity. Stated clearly in Buberian terms, Buchanan’s objections to orthodox methods become sharper and his insights gain greater depth. We contend that Buchanan’s view of man as a creative, entrepreneurial, artifactual being when combined with the Knightian moral-social stance amounts to insisting that an I-Thou mode of relations is foundational to all economic process. With that emphasis in mind, we again quote Buchanan:

[Human] behavior in the market relationship, reflecting the propensity to truck and to barter, and the manifold variations in structure that this relationship can take – these are the proper subjects for the economist’s study. (Buchanan, 1979, p. 19)

Buchanan did not explicitly use Buber’s precise vocabulary but what he describes is an I interacting with a Thou.

The difference between reactive choice of the orthodox models and Buchanan’s creative choice can be drawn along similar lines. The agent who is represented by a utility function, constrained by a budget, and who must choose among a pre-existing vector of goods, is merely reacting to external stimuli. No room for the creative entrepreneur opens in those models. If the individual is restricted to such a confining view, essentially no difference exists between the individual and the utility function. The agent becomes a mere mathematical object -- a computational device. He is little more than a rat, or a squirrel, or a machine. While objectification may give economics a mathematical-scientific veneer, it strips it of its essential nature. In such a setting, no creative arbitrage is possible. And, thus, no room for the emergence of the exchange process and the myriad of institutional structures and arrangements that make it possible. Although the appeal of scientific rigor seduces many economists (maybe even most), Buchanan bridles at the bargain. For, in toy mathematical models, individuals become automatons and markets become analogue computational devices that spit out equilibrium prices. That is a bridge too far for Buchanan: the single-minded pursuit of mathematical rigor yields to scientism.Footnote 5 While such economists may enjoy reputations as hard-nosed scientists, they do so at the price of becoming irrelevant (or worse, a real danger to the liberty of their fellows as they become “social engineers”, those chosen few with the skills and aptitudes for programing the complex machine).

To Buchanan, whose primary goal was to explain the emergence of exchange itself, economics represents a confused social science. Most important, it ignores the spontaneous order achieved by voluntaristic exchange. Starting from the preconditions necessary for equilibrium, the mathematical objects of the orthodox model simply are incapable of helping understand the evolving institutions, contracts, products, and services that make markets even possible in the first place. Equilibrium must perforce assume the pre-existence of those things. Only the creative [and fully human] entrepreneur meeting his fellows on a ground of mutuality could give rise to such complex phenomena. There is, Buchanan says, an authentically scientific aspect to economics, that of emergent spontaneous order. Its preconditions are rooted in a view of mankind that is relational, transactional, and to use the Buberian term, dialogical. We argue that it is essentially that of an I encountering a Thou in creative dialogue.

4.1 Temporal patterns

Consider the pairing of Buchanan’s symbiotics and Buber’s I-Thou. Also consider the pairing of the orthodox equilibrium models and Buber’s I-It. We can compare the two pairings in terms of their temporal modalities. As Fisher (1989, p. 1) has written, “Economic theorists are most often concerned with the analysis of positions of equilibrium.” Economic equilibrium is a broad and deep topic, but a general definition will suffice for present purposes. According to Bannock and Baxter (2011, p. 122), equilibrium is defined as follows:

A situation in which the forces that determine the behavior of a variable are in balance and thus exert no pressure on that variable to change. It is a situation in which the actions of all economic agents are mutually consistent. It is a concept meaningfully applied to any variable whose level is determined by the outcome of the operation of at least one mechanism or process acting on countervailing forces. For example, equilibrium price is affected by a process that drives suppliers to increase prices when demand is in excess and to undercut each other when supply is in excess - the mechanism thus regulates the forces of supply and demand.

One sees in that orthodox definition that the concept of equilibrium is essentially a product of static analysis. In recent decades, much work has been done embodying a more dynamic concept of equilibrium. But here, too, even though several variables are changing over time, they are doing so in steady, predictable ways. What is interesting about that way of modeling equilibrium are the assumptions that need to be made about the state of knowledge and the nature of the economic process. One readily detects the objectifying nature of it. In an analogy to physical machinery, the economy is described in deterministic language; it is viewed as a mechanism. The human players are objectified by their functions in the mechanistic process. Consumers in the models are “passive responders to stimuli”, as are producers who respond deterministically to conditions of excess demand or excess supply (Buchanan, 1979, p. 281). The knowledge in the economy is, for all intents and purposes, fully static. For that reason, the temporal modality is centered in the past. For the models to have a solution, objectification absolutely is necessary. Without it, the models would not serve their predictive purposes. To be predictive, the temporal orientation of the models always must be backward looking. We find the same temporal modality in Buber’s description of the I-It.

The I of the primary word I-It, that is, the I faced by no Thou, but surrounded by a multitude of “contents,” has no present, only the past. Put in another way, in so far as man rests satisfied with the things that he experiences and uses, he lives in the past, and his moment has no present content. He has nothing but objects. But objects subsist in time that has been.

The present is not fugitive and transient, but continually present and enduring. The object is not duration, but cessation, suspension, a breaking off and cutting clear and hardening, absence of relation and of present being.

True beings live in the present, the life of objects is in the past. (Buber, 1937, p. 11)

The concept of equilibrium in game theory becomes one of a “set of mutually compatible strategies in which, given the strategies of other players, each player will be content with his/her own strategy” (Bannock & Baxter, 2011, p. 124). One might think that game theory comes closer to modeling a situation of interpersonal exchange, but notice that individuals are still treated as mere “strategies”, that is, as objects. It remains inexorably linked to a means-end framework. The same temporal modality thus applies to even the most advanced concepts of equilibrium in economics, and forever must. Equilibrium, by definition, is static (even in its most sophisticated forms) and, therefore, must be oriented in the past along its temporal dimension. Again, Buber writes:

It does not matter how exclusively the Thou was in the direct relation. As soon as the relation has been worked out or has been permeated with a means, the Thou becomes an object among objects … fixed in its size and its limits. (Buber, 1937, p. 16)

Perhaps along the temporal dimension we find the tightest correspondence between the ideas of Buchanan and Buber. As we have remarked above, for Buchanan, the economy is a continuously and endogenously unfolding dynamic process. Key to understanding the process is to understand creative-artifactual choice by the entrepreneur. For Buchanan, the source of all creativity and novelty is embedded in the economic process. It is a process that must unfold over time and by its very nature is unpredictable. Buber describes the temporal modality of the I-Thou relation in almost identical terms as the spontaneously unfolding present. In the I-Thou pair, individuals are contemporaneous in their full humanity. Being present at the same time requires an openness to the unexpected and the unpredictable. It is such openness to another in dialogue that expands the moral depth of field of the individual as Buber’s I relates to a Thou; it is a kind of moral catallactics. Symbiotics is a term that also would apply. Like Buchanan, Buber views his dialectical process of relation as the source of all genuine creativity and becoming and transcendence. For Buber, “All real living is meeting.” (Buber, I and Thou, 1937, pp. 11–12).

The processes that Buchanan and Buber describe produce orders that are, as Adam Ferguson said, “the result of human action, but not the execution of any human design” (Ferguson, 1980). According to Buchanan, order cannot exist but for the process itself and process is where economists go astray. They speak of allocative results as if people have predetermined utility functions. But once we see market interactions as I-Thou interactions, the idea of predetermined utility functions becomes far-fetched. Individuals do not know how they will choose until they are faced with actually choosing, with interacting with another, or as Buber would say, a Thou. If human beings had predetermined utility functions, Buchanan argued often, “there is no genuine choice behavior on the part of anyone” (Buchanan, 1999, p. 244)). Even an omniscient god-designer could not say without destroying freedom of will what the allocative result would be apart from the process itself! Economists might build “as if” models post hoc, but the models do not capture what actually is unfolding in the market process; orders are genuinely spontaneous and emergent.

4.2 Entrepreneurship and creativity

Buchanan cites an example from Israel Kirzner that we will use here to draw out his thinking on the central role of entrepreneurship in economic theory.Footnote 6 In his paper on the proper domain of subjective economics Buchanan critiques Mises’s theory of praxeology.Footnote 7 His main contention is that Mises claimed too much territory for subjective economics and, in doing so, conflated two rather distinct forms of purposeful behavior. He employs the example from Kirzner to cut through the confusion

Consider two examples: (1) a man is walking along a road; he sees a car approaching; he jumps to the side of the road to avoid being run down. His action here is purposeful. It is surely aimed at removing a potential state [of] dissatisfaction and replacing it by one that is preferred. (2) A man is walking along a road barefooted. His feet are sore. He sees some cowhide and he imagines the possibility of shoes. He acts to make the shoes from cowhide…. This action is purposeful, and it, like the first, is surely aimed at replacing a state of dissatisfaction (sore feet) with one that is preferred. (Buchanan, 1982, pp. 14–15)

For Buchanan, the two scenarios represent two distinct forms of purposeful behavior: one that is objective and amenable to theoretical and empirical prediction, and one that is subjective and by its very nature not predictable. When the man jumps out of the way of the moving vehicle, he is acting purposefully in the sense of Mises’s praxeology. The action should not be understood as subjective, but rather as reactive choice, whereas in the second example of seeing cowhide, imagining a pair of shoes, and acting to bring about that transformation to alleviate his sore feet is an act of creative choice. This latter form of purposeful behavior is not predictable in any meaningful sense. The former is the kind of behavior that man shares with other animals, and again, Buchanan is wont to cite the rat studies to forcefully make this point regarding its scientific status. The latter springs from the deep well of human creativity and inventiveness; it is unique to the human species. The former is the domain of objective economics, and the latter is the proper domain of subjective economics. Regarding the different domains, Buchanan states

Theory or analysis can be of explanatory value in this domain without the attribute of operationality in the standard sense. Theory can add to our understanding (verstehen) of the process through which the economic world of values is created and transformed. Subjective economics offers a way of thinking about economic process, a means of imposing an intellectual order on apparent chaos without inferentially reducing the status of man, as a scientific object, to something that is not, in kind, different from that of animals. (Buchanan, 1982, p. 16)

.

For Buchanan, subjective economics remains scientific in the sense of lending intellectual order to the dynamics of economic process without reducing it to an objective science. It is in that aspect that subjective economics is a “very peculiar” (Buchanan, 1979, p. 280) and totally unique human science. Notice the convergence of Buchanan’s distinction between reactive (objective) and creative (subjective) choice and Buber’s modes of I-It and I-Thou. Borrowing the language of Buber’s moral philosophy, Buchanan is claiming that the mainstream of economics is guilty of basic modal confusion. By reducing the scientific status of humans to that of a fixed and reactive object (like a rodent), no vector exists by which to introduce novelty, creativity, and change into the economic system. The economy becomes a closed and limited system incapable of development and growth. That reductionist trend and its resultant epistemological confusion represent Buchanan’s strongest criticism of mainstream neoclassical economics. Buchanan emphasizes the warnings of both Frank Knight and Friedrich Hayek against scientism as requiring constant vigilance. (Buchanan, 1979, pp. 280–281)

Notwithstanding his strong criticism of scientism in mainstream economics, Buchanan likewise was wary of the lateral mistake of inflationary reasoning regarding the subjective domain of economics. As noted above, Buchanan directed criticism to Mises’s praxeology as claiming too much explanatory territory for the creative aspect of human choice. An objective domain of human behavior is amenable to scientific prediction. We may again adopt Buber’s modes to bear this out. One must not read Buber as totally negating and rejecting the I-It. Rather, Buber acknowledges that most of our interactions take place in the I-It mode. That conclusion is simply one of practical necessity. We cannot live in the world of abstractions that we have created without the useful simplifications that the I-It enables. The symbolic realm of words, numbers, and other abstractions make possible overcoming mere subsistence living and facilitates human development, growth, and becoming. The proper role of science thus is to employ symbolic systems to categorize, classify, and distinguish the world of nature. And there is little doubt that they have been of enormous value to the human family.

Buber had the following to say regarding the practical necessity of the I-It mode:

But this is the exalted melancholy of our fate, that every Thou in our world must become an It. It does not matter how exclusively present the Thou was in the direct relation. As soon as the relation has been worked out or has been permeated with a means, the Thou becomes an object among objects – perhaps the chief, but still one of them, fixed in its size and its limits. (Buber, 1937, pp. 16–17)

In a similar vein, one cannot read Buchanan as saying that all market activity is the operation of the subjective element of economics. Rather, most market activity takes place in the I-It mode. Day to day economic transactions operate by and large through the I-It mode in the sense of being repetitive, routine, and regular. Exchanges mediated by prices denominated in currency require fixity and regularity. For both Buchanan and Buber, it is essential that the importance of repetition be well understood to avoid modal confusion. Menus are practical abstractions to facilitate the ordering of food, but one cannot derive nutrition from them by attempting to eat them instead of the meal. Likewise, as Hayek enlightened us, the price mechanism coordinates an incomprehensibly vast network of economic interactions, but no one ever obtained caloric energy by consuming a dollar bill. Buchanan’s plea to economists is to keep those things separate so that they may retain clarity and not unnecessarily complicate their most important didactic task of explaining spontaneous economic order.Footnote 8

Buchanan calls upon Adam Smith and classical economics to cut through the haze of confusion. Adam Smith, Buchanan claims, primarily was interested in developing an economic theory to explain not just the relative values of commodities, but also the emergence of the institutions of exchange per se. He cites the now famous deer-beaver illustration as a concrete example of exchange values. To explain exchange values, Smith had to account for the emergence of exchange itself. Why and how did exchange and its necessary liberal institutions evolve in the first place? For Buchanan, the answer is the Smithian trader endowed with the innate and uniquely human propensity to truck, barter, and exchange. Buchanan thus reads Adam Smith as a thoroughgoing subjectivist and points out that such understanding of Smith has been neglected by the mainstream of the discipline. In Buberian terms, we may say that Buchanan insists that nearly from the start economists have floundered intellectually under modal confusion.

We now point to the unique way in which Buchanan used the word arbitrage.

Economics is about arbitrage. The behavioral paradigm central to economics is that of the trader whose Smithean propensity to truck and barter locates and creates opportunities for mutual gains. This paradigm is contrasted with that of the maximizing engineer who allocates scarce resources among alternatives…. [T]he maximization paradigm is the fatal methodological flaw in modern economics (Buchanan, 1979a p. 281; emphasis in original).

Notice that, for Buchanan, arbitrage is an act of creative choice and not merely the reactive choice implied by relative price discrepancies. The arbitrageur is an entrepreneur who locates and creates symbiotic potential in the catalexis. The Buchananian arbitrageur literally is a market-maker who transcends established patterns and introduces the institutions of exchange within which the relative prices of commodities subsequently come to be calculated. The convergence with Buber’s two modes is striking. In a pre-exchange setting, patterns of interaction are characterized by regularity and from such regularity an objective science may make predictions. It is the world of I-It constrained and limited in its fixity. The creative act of the arbitrageur represents a moment of I-Thou in human affairs that introduces new modes of interaction and exchange not previously existing. Buber’s “exalted melancholy of our fate” is that a new Thou comes into our world and takes its place as an It – an object among other objects. In the post-exchange setting, new patterns of regularity may be established and from then on an objective science may again make its predictions. But what in economic theory accounts for the quantum leap between the pre-exchange and post-exchange settings? That is the purely human-creative element of economics.

An economy (if indeed it could be called such) in which all persons respond to constraints passively and in which no one engages in “active” choice could never organize itself through exchange institutions. (Buchanan, 1982, p. 9)

To cast that conclusion in terms of our earlier examples, we may say that the day-to-day use of menus to order food is a fixed and regular It, but the introduction of the very first menu in history was a moment of pure human inventiveness in the mode of Thou. The financial economist may employ standard no-arbitrage theory to value an option contract relative to its replicating portfolio, but the first moment in history when a market-maker posted bid-and-offer prices established a completely novel contracting structure. The world never was the same thereafter. The most salient form of arbitrage for Buchanan is the market-maker who first posts bid and offer prices on an option contract rather than the trader who takes advantage of fleeting price discrepancies in a previously established market. Financial economists proceed simply by assuming that option markets exist. For Buchanan, by far the more interesting question is “from whence did they arise?”

The man jumping out of the way of the moving vehicle is a form of objective behavior that the man shares with other animals in the mode of I-It. As such, it is amenable to scientific modeling and prediction. Buchanan refers to such behavior as reactive choice. He does not doubt the scientific status of the objective domain of economics and recognizes that much of human behavior in market settings necessarily belongs to that mode. The man walking with sore feet who imagines shoes from cowhide begins to hint at the I-Thou mode of human behavior in the exchange setting. The imaginative element of the hide-shoe example is what Buchanan refers to as creative or active choice. But the latter case needs to be developed with care. Buchanan has in mind something quite subtle and deep when placing the Smithian arbitrageur at the center stage of market processes. It must be understood that he does not stop at the inventive or imaginative origins of human creativity. The man seeing the cowhide and merely imagining shoes is not yet what he refers to as arbitrage. Rather, it is a point of departure for his deeper development.

Another example from Kirzner may help to elucidate the same point.Footnote 9 Kirzner discusses a situation in the Robinson Crusoe setting wherein the agent imagines making a net or constructing a boat to catch more fish than with his bare hands. For Kirzner, that innovation is an example of Miesian entrepreneurship. The reallocation of Crusoe’s time and labor leads to a pure profit opportunity. Alertness to that kind of entrepreneurial discovery represents Kirznerian arbitrage. It almost is the traditional definition of the word arbitrage as used commonly in economics but with one subtlety. For Kirzner, alertness is an act of entrepreneurial creativity that introduces a new possibility and thereby expands the agent’s opportunity set. However, in an economy characterized by complete markets, such possibilities would be priced and the reallocation would be an example of the kind of reactive arbitrage that amounts to noticing relative price discrepancies in Crusoe’s setting. For Buchanan, reactive behavior does not yet amount to full creative arbitrage. He does not dismiss the imaginative component of the creation of new possibilities and does indeed understand it as entrepreneurial activity of the second sort. It is more akin to seeing cowhide and imagining shoes than it is to jumping out of the way of the moving vehicle. Kirzner’s example represents the creative component that aids the completion of the market, but only in the strictures of the Crusoe setting. Buchanan reminds us that “the uniquely symbiotic aspects of behavior, of human choice, arise only when Friday steps on the island, and Crusoe is forced into association with another human being” (Buchanan, 1964, p. 217). Kirzner’s example is not yet what Buchanan means by arbitrage by the Smithian trader because it neither involves exchange nor the creation of new markets. Recall that Buchanan preferred the term symbiotics to catallactics; thus, when he uses the latter, he means something more than the purely Misean entrepreneurship that others may intend by the term.

We emphasize that that form of Buchananian arbitrage always is in the I-Thou mode, while Kirznerian arbitrage may or may not represent the I-Thou mode. Recall that Buber applied his modes of being in three different domains: humans’ relation to nature, humans’ relations to one another, and humans’ relation to spiritual life. We have applied the convergence between Buchanan’s and Buber’s philosophies exclusively to the human domain. Buber would recognize Kirzner’s example of creating a net or building a boat as belonging to the I-Thou mode, but surely not Crusoe’s exploitation of Friday as his slave. Buchanan’s symbiotics excludes the latter a priori. Thus, entrepreneurship is both necessary and sufficient for Buchanan’s form of catallactics, but only as understood in that fuller sense. The arbitrage of the Smithian trader is the two-step process of locating and then creating opportunities for mutual gain. Its status as belonging to the I-Thou mode always is unambiguous.

4.3 Linguistic patterns

Buber pointed out that one of the main indicators of whether one is in an I-It or an I-Thou mode is to observe the way the word I is used. Usage becomes a touchstone for the way one is addressing the world, “For the I of the primary word I-Thou is a different I from that of the primary word I-It” (Buber, 1937, pp. 1–2).

The I-It way of using the word I corresponds to a self-centered and egoistic means of addressing another human the way one would address any other object. The same pattern is common in day-to-day life out of simple, practical necessity. In contrast, Buber points to the way that Socrates, Goethe, and Jesus used the word I in a very non-egoistic manner. Of Socrates as a positive example, Buber writes:

[H]ow lovely and how fitting the sound of the lively and impressive I of Socrates! It is the I of endless dialogue.… This I lived continually in the relation with man which is bodied forth in dialogue. It never ceased to believe in the reality of men and went out to meet them (Buber, 1937, pp. 65–66).

Thus, looking at the common linguistic patterns in economics should be telling. One might well ask which of Buber’s two modes of relation an analysis of the language of modern economic theory will reveal. By contrast, which mode will the writings of James Buchanan reveal? Let us consider the following thought experiment. Our linguistic investigation is an introductory exercise. It is not meant to be exhaustive, but rather suggestive. A broader and more thorough investigation is left for further research.

Johansson (2004) examined the vocabulary found in graduate level textbooks used in doctoral programs in Swedish graduate schools of economics.Footnote 10 His exercise bears remarkable similarities to the one just proposed. He investigates what he terms entrepreneurship-rich and institutions-rich theories as represented in graduate level textbooks. Those categories are familiar to anyone acquainted with Buchanan’s research program, as well as to those who have read thus far.Footnote 11 Regarding his survey, Johansson writes:

The terms naturally break down into dual sets. One deals with knowledge and discovery: entrepreneur, innovation, invention, tacit knowledge, and bounded rationality. The other deals with social rules: institutions, property rights, and economic freedom. (Johannson, 2004, pp. 516–517)

Three main points from his study are relevant to our theme:

-

(i)

By and large, the eight expressions scarcely appear in the textbooks (pp. 526–527).

-

(ii)

When they do appear, “the meaning and significance of the ideas are lost, diluted or distorted” compared to their meaning in theories where the idea is more central (p. 527).

-

(iii)

“This investigation implies that the theory underlying all PhD programs in economics in Sweden excludes what chiefly explain economic growth and general wealth—entrepreneurship and private property rights” (p. 531).

Johansson concludes that “… the problem we have with economics is not the training we do have, but the training we do not have” p. 538).

A particular example found in the most popular graduate level microeconomic theory is telling. In the leading microeconomic theory textbook, the term entrepreneur appears just once. The reference is in an exercise at the end of a chapter titled “Adverse Selection, Signaling, and Screening.” In the example, an “entrepreneur” goes to the bank to borrow funds, and a signaling exercise is set up for the student to solve (Mas-Colell et al., 1995, p. 475). Johansson points out that the “entrepreneur is not mentioned at all in the fundamental function she undertakes in Schumpeterian or Kirznerian theory but could be any borrower at all” (Johannson, 2004, p. 527). One wonders if the borrower need be human.Footnote 12

In addition to the considerable evidence provided by Johansson (2004), we here provide a few selections from textbooks found on our shelves. The following exercise is found at the end a chapter titled “Choice and Demand” (Nicholson, 1998, p. 120).

-

a.

Mr. Odde Ball enjoys commodities X and Y according to the utility function.

$$U\left(X,Y\right)= \sqrt{{X}^{2}+{Y}^{2}}.$$Maximize Mr. Ball’s utility if PX = $3, PY = $4, and he has $50 to spend.

Hint: It may be easier here to maximize U2 rather than U. Why won’t this alter your results?

-

b.

Graph Mr. Ball’s indifference curve and its point of tangency with his budget constraint. What does the graph say about Mr. Ball’s behavior? Have you found a true maximum?

While no I is spoken of there, we can examine its subject. The semantic content of the exercise would not change one bit if the reader were informed that instead of being a human being, Mr. Odde Ball were a robot or a software agent.

An additional example is also instructive. Again, this is an end-of-chapter exercise on the topic of production (Varian, 1992, p. 357).

Consider an economy with two firms and two consumers. Firm 1 is entirely owned by consumer 1. It produces guns from oil via the production function g = 2x. Firm 2 is entirely owned by consumer 2; it produces butter from oil via the production function b = 3x. Each consumer owns 10 units of oil. Consumer 1’s utility function is \(u(g,b) = g^{4}b^{6}\) and consumer 2’s utility function is \(u(g,b) = 10 + 0.5 {\rm In} \,b\).

-

a.

Find the market clearing prices for guns, butter, and oil.

-

b.

How many guns and how much butter does each consumer consume?

-

c.

How much oil does each firm use?

The meaning of the exercise remains unchanged if, instead of having utility functions (or production functions) Consumer 1 and Consumer 2 were utility functions. The language of the examples reveals an imagined world entangled in and bound up with It.

A final example is arresting in its clarity. In a podcast discussion on the economics of slavery, Roberts and Munger (2016) discuss the history of slavery in the American South. In their discussion, Roberts and Munger chat about the economic value of a slave, which rose after slavery importation was banned by the American Constitution in 1808. Their discussion proceeds as follows:

Munger

[T]hat just meant slaves were more valuable. The cotton gin, the spinning mule, the jenny – those things that allowed the industrialization of the production of cotton thread and textiles meant that slaves doubled in price, and then doubled again… the slave’s price is the present value of its – implicit wages that that person is earning over time.

Roberts

It should accrue to the owner, instead. Yeah?

Munger

It should accrue to the owner. Because it’s as if the person were a horse. So, if I rent out a horse, and the horse is strong and is good at work, it’s valuable.

Naturally Roberts and Munger condemn slavery, and the discussion centers around the economics of slavery. Because the discussion proceeds in the vocabulary of economic theory, however, it is couched in terms of It. They point out that in the history of the American South, a slave was treated as the present value of the labor that accrues to his owner. As Munger says, “it’s as if the person were a horse”, or, we might add, a machine. We can compare Munger’s characterization to that of Nicholson (1998, p. 703) on the rate of return on capital:

Consider a firm in the process of deciding whether to buy a particular machine. The machine is expected to last n years and will give its owner a stream of monetary returns (that is, marginal revenue products) in each of the n years. Let the return in year I be represented by Ri. If r is the present interest rate, and if this rate is expected to prevail for the next n years, the present discounted value (PDV) of the net revenue flow from the machine to its owner is given by:

$$PDV=\frac{{R}_{1}}{1+r}+\frac{{R}_{2}}{{\left(1+r\right)}^{2}}+ \cdots +\frac{{R}_{n}}{{\left(1+r\right)}^{n}}$$

While modern economists might find the comparison of a slave to a horse or machine to be distasteful, they will also find it to be technically correct. We see in this striking example why Buchanan was concerned about the language of economics being transformed from the social-institutional to the physical-computational. He warned economists that with an undue emphasis on their mathematical models:

And further, as we cited above, in such a setting:

The “market” becomes an engineered construction, a “mechanism,” an “analogue calculating machine,” a “computational device”. (Buchanan, 1964, p. 219)

Buber would point out that the foregoing extreme example is indicative of a scientific discipline that is unbalanced in the direction of the I-It and needs to be balanced with more I-Thou content to restore its humanity. Buchanan would agree. In his symbiotics, a model that rationalizes the discounted cash flow analysis of a human being would crepitate in its extreme cognitive dissonance. If economists followed Buchanan in viewing economics as interpersonal exchange between characterized by mutuality and reciprocity such a model would create extreme discomfort. That is as it should be. Other methods, in the direction of moral philosophy, need to be brought in to restore the model’s human content.

An alien observer of our planet who first looked to our economics textbooks might well decide that they are instruction manuals for multiagent software systems (Wooldridge, 2009) and have nothing whatsoever to do with human organization.

In 1950, the mathematician and early computer scientist Alan Turing proposed a test of artificial intelligence that has come to be known as the Turing Test (Turing, 1950). The test proceeds with a human judge carrying on a natural language conversation with two veiled entities, one of which he knows to be human and the other to be a machine. If the judge cannot tell the difference between the human and the machine, the conclusion is that the machine is intelligent. Finding the widespread interpretation of Turing to be incomplete, Lanier (2010, p. 29) states:

It seems to me, however, that the Turing test has been poorly interpreted by generations of technologists. It is usually presented to support the idea that machines can attain whatever quality it is that gives people consciousness. After all, if a machine fooled you into believing it was conscious, it would be bigoted for you to still claim it was not.

What the test really tells us, however, even if it’s not necessarily what Turing hoped it would say, is that machine intelligence can only be known in a relative sense, in the eyes of a human beholder.

The Turing Test presents a joint hypothesis problem. If a machine is indistinguishable from a human, is it because the machine has gained human-level intelligence, or is it because the human has become a mere machine? We put forth the proposition that had homo economicus been encoded into a software system in Buchanan’s time, he would not have been overly impressed with its ability to pass the Turing Test. We propose a much stronger test of human ability, which we call the Buber Test:

If an Artificial Intelligence is capable of taking a stand in relation to a Thou as an I, then it has become a Being of human-like ability.

We suggest that Adam Smith’s trader with “the propensity to truck, barter and exchange” passes such a test.

4.4 The Robinson Crusoe economy

In this section, we present the Robinson Crusoe Economy (RCE) of standard textbook analysis. We present the RCE as the background for a dialogue between Buchanan and Buber.

The so-called RCE is a very common pedagogical device found in textbooks and articles in both the neoclassical and Austrian economics traditions. For an example in a mainstream neoclassical textbook see Varian (1992). For an example of its use in the Austrian tradition see Spitznagel (2013), who relies on it to discuss his idea of the roundaboutness of production. The RCE is a hypothetical economic setting of an isolated individual modeled as a planned economy without market exchange. The model is named for the central character in the Daniel Defoe’s (1895) famous novel Robinson Crusoe.

The RCE has been adopted in the Austrian tradition to model the dynamic nature of the capital structure of an economy. In the neoclassical tradition, it is relied on mainly to introduce the key methodological tools of constrained utility optimization in an equilibrium setting. Crusoe finds himself shipwrecked on a deserted island and must make choices regarding the tradeoff between his labor and leisure. Again, the main tool of utility maximization subject to a budget constraint is introduced to solve the economic calculation that Crusoe finds himself confronting. It is in this neoclassical setting that we will employ the RCE as meeting ground for the economic ideas of James Buchanan and the philosophical ideas of Martin Buber.

4.4.1 Robinson Crusoe storyline

The story that is told in economics textbooks is contrary to the actual storyline. It is clear from reading the novel that when Friday arrives on the island, Crusoe views him as a device to accomplish his own goals. He insists on Friday calling him Master. In fact, when teaching Friday to speak English, Crusoe instructs Friday to call him Master before he even teaches him the words yes and no. To quote from the book:

I understood him in many things, and let him know that I was very well pleased with him. In a little time I began to speak to him, and teach him to speak to me; and, first, I made him know his name should be Friday, which was the day I saved his life, and I called him so for the memory of the time: I likewise taught him to say Master, and then let him know that was to be my name: I likewise taught him to say Yes and No, and to know the meaning of them. (Defoe, 1895, p. 262)

If one were to re-read this passage replacing the words him and his with the words it and its, the real meaning of the words would become much clearer. We see that the I that is spoken here belongs to the I-It.

I understood it in many things, and let it know that I was very well pleased with it. In a little time I began to speak to it, and teach it to speak to me; and, first, I made it know its name should be Friday, which was the day I saved its life, and I called it so for the memory of the time: I likewise taught it to say Master, and then let it know that was to be my name: I likewise taught it to say Yes and No, and to know the meaning of them.

With that background, we present a dialogue between Buchanan and Buber in the next section.

4.4.2 Dialogue between Buchanan and Buber

What follows is a brief conversation between Buchanan and Buber as we have imagined it. We join them just after they have made one another’s acquaintance.

Buber

I’ve been reading your economics textbooks, and I have read about the Robinson Crusoe economy. Can you tell me more about it?

Buchanan

Most economists conceive of it as follows: “Robinson Crusoe, on his island before Friday arrives, makes decisions; his is the economic problem in the sense traditionally defined. This choice situation is not however, an appropriate starting point for our discipline, even at the broadest conceptual level, as Whately correctly noted more than a century ago” (Buchanan, 1964, p. 217).

Buber

You disapprove of how most economists frame the problem?

Buchanan

I do.

Buber

Can you tell me why?

Buchanan

“Crusoe’s problem [as traditionally framed] is, as I have said, essentially a computational one, and all that he need do to solve it is to program the built-in computer that he has in his mind” (Buchanan, 1964, p. 217).

Buber

What is wrong with that?

Buchanan

“The uniquely symbiotic aspects of behavior, of human choice, arise only when Friday steps on the island, and Crusoe is forced into association with another human being… [Crusoe] may treat Friday simply as a means to his own ends, as a part of nature, so to speak. If he does so, a fight ensues, and to the victor go the spoils. Symbiotics does not include the strategic choices that are present in such situations of pure conflict” (Buchanan, 1979, p. 28).

Buber

I am impressed with your concept of symbiotics. Can you tell me more about it?

Buchanan

“The very word economics, in and of itself, is partially responsible for some of the intellectual confusion. The ‘economizing process’ leads us to think directly in terms of the theory of choice…. Symbiotics is defined as the study of the association between dissimilar organisms, and the connotation of the term is that the association is mutually beneficial to all parties. This conveys, more or less precisely, the idea that should be central to our discipline… important elements of the theory of choice remain in symbiotics. On the other hand, certain choice situations that are confronted by human beings remain wholly outside the symbiotic frame of reference” (Buchanan, 1964, pp. 216–217).

Buber

Yes, I have also read the novel Robinson Crusoe. In the story, Crusoe first tries to enslave Friday.

Buchanan

Yes.

Buber

Economics textbooks would allow the slave to be thought of as the present discounted value of the return on the slave’s labor that accrues to its owner. What do you think of this?

Buchanan

This is precisely the kind of thing that I object to. I consider it intellectual muddle. Again, symbiotics, as I conceive of it, does not include such situations.

Buber

When an I speaks of another as an It, the I is spoken in the pairing. That is, by treating another being as chattel, he himself becomes a psychopath. Our existence is relational. How you relate to others determines who you will become.

Buchanan

I think I agree with that statement. When I look at my own discipline, I think economists of this sort sorely miss the boat. In my symbiotics, there is no such view of man.

Buber

Your symbiotics embodies an I-Thou approach to economics. I commend you for your humanity.

Buchanan

Well, I don’t know about that. Perhaps it’s only a relatively absolute absolute. But from the very start [from that day in Frank Knight’s classroom], the deep wonder that has occupied my attention as an economist seems impossible without the pre-conditions of mutuality and reciprocity. I am convinced that spontaneous order is an outcome only possible between creative human beings and not between mere computational units. It is an order defined in the process of creative choice. Humans are the only ones capable of this kind of choice. Without actors there is no play (Buchanan, 1979, p. 281)!

Buber

Would you say mutuality and reciprocity is only between humans and not objects?

Buchanan

Yes, I think I would.

Buber

Between Thous and not Its?

Buchanan

I see your point. Your case is compelling. It certainly fits, at least on some level with what my old teacher Frank Knight taught me.

Buber

I thank you for this discussion… this dialogue if you will.

Buchanan

I’m very grateful for this exchange, and the pleasure has been all mine. Thank you.

5 Conclusion

The landscape of James Buchanan’s catallaxy is richly populated with the Smithian trader, the artifactual man who engages in mutually beneficial exchange with his fellows. In his scholarship, we see a vision of economics that called us to think deeply about human exchange and emergent processes. Well might Martin Buber have said of him as he said of Socrates:

But how lovely and how fitting the sound of the lively and impressive I of James Buchanan! It is the I of endless dialogue. This I lived continually in the relation with man which is bodied forth in symbiotics. It never ceased to believe in the reality of men and went out to meet them (Buber, I and Thou, 1937, pp. 65–66).

Notes

To clarify, we note that what we mean here is that exchange could not originate from the preconditions of an equilibrium setting. Equilibrium assumes consummated exchange so that any argument of the emergence of exchange from those conditions would be circular. We certainly are not claiming that equilibrium could not emerge from out of a non-equilibrium setting. Progress in agent-based modeling and evolutionary game theory has successfully demonstrated the latter point.

We borrow the phrase with appreciation from Martin (2011).

Recall that the Latin name means “wise man.”

This imagery is inspired by (Watts, 2011).

We emphasize that Buchanan did not oppose mathematical rigor per se. Rather he opposed the reduction of all of economics to mere mathematical modeling. Sometimes math simply is the wrong abstraction, or an abstraction that should be complemented by other methods to avoid losing the humanity of the subjects being modeled.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting the example.

The direction we take here is complementary to Martin (2020).

In an impressive moment of humility, Buchanan admits to his own intellectual floundering until he himself realized the same point (See Buchanan 1982, p. 17).

Again, we wish to thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this additional example from Kirzner to aid the development of our theme.

Johansson points out that his analysis applies much more broadly than just to Swedish graduate programs. They, and many others are structured after North American graduate economics programs.

Indeed, Johansson cites Buchanan to summarize his survey.

Johansson refers to Schumpeter’s comparison of the entrepreneur’s missing place in economic theory to the Prince of Denmark being absent from Hamlet (p. 532).

References

Bannock, G., & Baxter, R. (2011). The Penguin dictionary of economics. Penguin Books.

Buber, M. (1937). I and thou. Public Domain.

Buber, M. (1937). I and thou (R. G. Smith, Trans.). Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

Buchanan, J. M. (1964). What Should Economists Do? Southern Economic Journal, 30(3).

Buchanan, J. M. (1979). What should economists do. Liberty Fund Inc.

Buchanan, J. M. (1982). The domain of subjective economics: between predictive science and moral philosophy. In I. M. Kirzner (Ed.), Method, process, and Austrian Economics: essays in honor of Ludwig Von Mises. Lexington Books.

Buchanan, J. M. (1992). Better than plowing and other Personal Essays. University of Chicago Press.