Abstract

Multiparty government has often been associated with poor economic policy-making, with distortions like lower growth rates and high budget deficits. One proposed reason for such distortions is that coalition governments face more severe ‘common pool problems’ since parties use their control over specific ministries to advance their specific spending priorities rather than practice budgetary discipline. We suggest that this view of multiparty government is incomplete and that we need to take into account that coalitions may have established certain control mechanisms to deal with such problems. One such mechanism is the drafting of a coalition agreement. Our results, when focusing on the spending behavior of cabinets formed in 17 Western European countries (1970–1998), support our claim that coalition agreements matter for the performance of multiparty cabinets in economic policy-making. More specifically, we find clear support for an original conditional hypothesis suggesting that coalition agreements significantly reduce the negative effect of government fragmentation on government spending in those institutional contexts where prime ministerial power is low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Beginning with the modern “classics” (Bryce 1921; Lowell 1896), political science has distinguished between “strong” and “weak” governments; coalition cabinets are assumed to belong to the latter category. While initially the claim was that only the former provided for political stability and effective government, more recently the argument ties “weak governments” to lesser economic efficiency (slower growth rates, larger budget deficits, higher public debt, and so on). One proposed reason for such distortions is that coalition governments face more severe “common pool problems”, since parties use their control over specific ministries to advance their specific spending priorities rather than practice budgetary discipline (e.g., Hallerberg and von Hagen 1999).

We argue that we need to take a closer look at the operation of coalition governments in order to understand the relationship between types of governments and economic policy-making. We address the question of how coalition governments handle economic policy-making by focusing on government spending as our dependent variable, following the work of several previous authors; most recently, Bawn and Rosenbluth (2006) and Martin and Vanberg (2013).

We draw on the recent literature on coalition governance mechanisms (see, e.g., Müller and Strøm 2008), which suggests that certain control mechanisms, such as the drafting of comprehensive policy agreements or “contracts”, determine the ability of coalition governments to limit the policy discretion of individual parties in their ministerial jurisdictions. This type of argument is also very much in line with the work by “fiscal institutionalists” who suggest that negotiated spending targets for each ministry can lead to smaller deficits (see, e.g., von Hagen and Harden 1995). We therefore hypothesize that the structural weaknesses of multiparty government can (partly) be offset by mechanisms of coalition governance. More specifically, we focus on the role of “coalition agreements”, and we evaluate a hypothesis saying that, in the presence of a comprehensive coalition agreement, the impact of government fragmentation on public spending is mitigated. In addition, we elaborate on a new conditional hypothesis, suggesting that coalition agreements mitigate common pool problems in multiparty cabinets only in certain institutional settings, more specifically, when prime ministerial (PM) power is weak, or, differently put, when power is symmetrically distributed in the cabinet.

Our results, when focusing on the spending behavior of cabinets formed in 17 Western European countries (1970–1998) support our claim that coalition agreements matter for the performance of multiparty cabinets in economic policy-making. More specifically, we find clear support for the hypothesis that coalition agreements significantly reduce the effect of government fragmentation on government spending in those contexts where PM power is low. Hence, in institutional settings without power asymmetries in the cabinet, coalition agreements should help to resolve potential common pool problems resulting from multiple parties having different spending priorities.

2 Theory and hypotheses

2.1 The previous literature on types of governments and economic policy-making

Traditionally, analyses of economic policy-making have focused on economic explanatory variables. In recent years, more consideration has been given to how political variables affect various policy outcomes, including fiscal policy (e.g., size of government, budget deficits) and corruption. These political variables include the number and divergence of veto players (Tsebelis 2002; Hallerberg and Basinger 1998) and fundamental political institutions such as electoral systems, and their indirect effects in coalition governments (see, e.g., Persson and Tabellini 2003, 2006; Persson et al. 2003, 2007; Tavits 2007) .

Several scholars have also argued that the type of government should influence the size of the public sector, and the main prediction is that coalition governments, or a larger number of parties in cabinet (government fragmentation), should increase public spending. Bawn and Rosenbluth (2006, p. 251) argue that “coalitions of many parties will strike less efficient bargains”, owing to the fact that a number of electoral interests are represented in such cabinets, which should lead to a larger public sector. Persson and Tabellini (2006, p. 732) argue similarly that, when the government relies on a single-party majority, the competition between incumbent and opposition “pushes the incumbent towards efficient policies”, whereas coalitions are more likely to create electoral conflict, which induces excessive government spending. Bawn and Rosenbluth (2006) show that a larger number of governing parties is indeed related to more government spending. The subsequent literature has consistently supported the claim that public spending is higher under coalition governments than under single-party cabinets and increases with the number of parties (e.g., Blais et al. 2010; Martin and Vanberg 2013; Persson et al. 2007; Volkering and de Haan 2001).Footnote 1

Why then are coalitions prone to produce less satisfactory budgetary policies than single-party cabinets? Several scholars argue that coalition governments face more severe “common pool problems”.Footnote 2 For example, Hallerberg and von Hagen (1999, p. 212) argue that “each minister determines the spending priorities of her department, but she does not consider the full marginal tax burden”, which is more problematic in coalitions since the Finance Minister is less likely to be able to control ministers from other parties. Hence, coalition governments, or cabinets with more members, should be more prone to budget deficits because of such common pool problems.Footnote 3

The important result that coalitions spend more and incur larger budget deficits, an effect that increases with the number of parties, leads to the research question we pursue in this paper: even if coalitions in the aggregate are inferior in terms of budget restraint, can coalition builders avoid or significantly contain the financial problems resulting from the common pool problems highlighted above?

We are not the first ones to address this research question. Some scholars have argued that the problem of excessive public spending can be mitigated by various political–institutional features. The so-called “fiscal institutionalist” literature has identified some institutional rules that are expected to curb government spending. One such institutional remedy follows a “delegation approach” and suggests that the common pool problem may be reduced by delegating veto rights to certain offices, such as the Minister of Finance, not bound by the particular interests of any spending department, as they will give more weight to the collective interest of the government, such as keeping a balanced budget (e.g., von Hagen and Harden 1995). However, the delegation approach is often seen as most feasible for single-party cabinets since in coalitions no single office holder enjoys the trust of all government parties. Partisan Ministers of Finance thus would be suspected to benefit ministers from their own party or ideology and, hence, coalitions would not delegate this power or find political means to circumvent existing formal rules stating such rights.Footnote 4 Instead, coalitions are more likely to adopt a so-called “contract approach”, particularly those cabinets characterized by large ideological distances and vigorous competition between the cabinet parties (Hallerberg et al. 2007, 2009; de Haan et al. 2013). This approach suggests that coalitions aim at negotiating overall spending targets and rules at the beginning of the term and each minister works under preset spending limits.

Another way to contain government spending identified by fiscal institutionalists is to rely on fiscal rules that subject budget decisions to specific constraints (von Hagen and Harden 1995; Hallerberg et al. 2007, 2009). Martin and Vanberg (2013) have studied how the existence of these fiscal rules—amendment limits, restrictions on budget size, and offsetting amendments—affect the coalition parties’ abilities to increase the spending of “their” ministries and to prevent their partners from increasing the expenditure of the departments under their control. They find such rules to be effective instruments that significantly mitigate or even eliminate the pressure on government spending resulting from the presence of multiple parties in government.

Fiscal rules typically are engrained in public laws and often inherited by incoming coalitions. Still, their working in practice depends on how the rules are interpreted and how strictly they are observed. This is particularly important in financial planning as both income and expenditure forecasts critically depend on the quality of the assumptions that go into their estimation. Overly optimistic assumptions and laxness and delays in monitoring the implementation of budgets can cause significant deviations from spending plans and drive budget deficits. In short, fiscal institutions may fail if political cooperation is lacking.

We suggest that contributions can be made by drawing on the literature on delegation in coalitions, where the importance of other government features than the ones described above have been stressed. This literature is briefly introduced below.

2.2 Delegation problems in multiparty governments

The structural weakness of coalition governments is the dividing line between the cabinet parties. Ministers adhere to individual parties and their interests rather than to the collective goals of the coalition (Martin and Vanberg 2011; Müller and Meyer 2010a, b). While party interests may counterbalance individual incentives in single-party governments, they strengthen individual departmental rationales in coalitions. The government parties have their own identities, electorates, and policy concerns and they have to go through elections in their own right, competing also with their coalition partner(s). In elections, these parties may fight for their survival, continued government participation, or shares of office spoils and their party record in government may be more important for their electoral fate than the government record in general. This is the mechanism that is behind common pool problems in the budgetary policies of coalition governments.

The common pool problem rests in the so-called “portfolio allocation model” presented by Laver and Shepsle (1996). The portfolio allocation model is based on the assumption that each policy dimension is governed by a particular portfolio, and that the minister of a department has considerable discretion in acting on his or her own within the jurisdiction of the portfolio. Hence, each ministerial portfolio is allocated to one of the coalition parties, and there is “no mechanism by which any other party can prevent the portfolio holder from implementing its ideal point within that jurisdiction” (Strøm et al. 2010, p. 523). This type of coalition governance has been called “ministerial government” (Strøm 1998), or “fiefdom government” in the fiscal institutionalist literature (Hallerberg 2004), which stresses the autonomy of ministers.

However, such a “ministerial government” model does not provide a completely realistic description of how coalition governments function in parliamentary democracies. In the real world of coalition politics, governments do not cede complete autonomy to individual cabinet ministers or department heads.Footnote 5 Instead, coalition governments may impose various rules to control individual ministers and to overcome problems of decision-making and delegation in multiparty governments, and we suggest that this may have important consequences for our predictions about how coalitions function in terms of economic policy-making. At the same time, holding a particular portfolio gives the respective party strong (though not exclusive) influence over the policy-making in the respective domains and the other parties’ abilities to veto decisions are constrained considerably. We thus draw on the growing literature on coalition governance mechanisms (e.g., Strøm et al. 2010) .

2.3 Coalition governance and hypotheses about public spending

We argue that the relationship between government fragmentation and policy-making is more complex than the previous literature has suggested—increasing the number of governing parties does not necessarily produce distortions. In this section, we present hypotheses about the role of coalition governance mechanisms, in economic policy-making, based on the idea that some of the structural weaknesses of multiparty government can (partly) be compensated by mechanisms of coalition governance. Hence, the effect of the number of parties in cabinet (government fragmentation) on spending and economic reform behavior should be conditional on some political–institutional features.

As mentioned above, however, most work within the field has focused on fiscal institutions. This literature has suggested two main strategies for fighting the common pool problem: fixed numerical budget targets and restrictive procedural rules. Numerical targets, such as a balanced-budget law, are “neither necessary nor sufficient to ensure fiscal discipline” (Alesina and Perotti 1999, p. 16). The literature on procedural restrictions has identified some institutional rules that are expected to curb government spending. As discussed above, the simplest procedural remedy to the common pool problem—giving veto rights to offices not bound by the particular interests of any spending department—is unlikely to work in coalition cabinets. Rather, fiscal institutionalists suggest that coalitions, particularly those characterized by large ideological distances and a strong competition between the cabinet parties, would adopt a contract approach (Hallerberg et al. 2007, 2009; de Haan et al. 2013).Footnote 6 Accordingly, such coalitions would aim at negotiating overall spending targets and rules at the beginning of the term so that each minister would work thereafter under preset spending limits.

These arguments made in the literature on fiscal institutions can straightforwardly be connected to an argument about the role of coalition agreements. Such agreements may, for example, contain explicit spending limits (Hallerberg 2004), but also other policy commitments of which the costs may be uncertain. It is not always clear what the actors consider more important: sticking to the budget targets or, alternatively, to policy commitments for which increased spending is desirable electorally. More generally, ex ante mechanisms cannot account for all contingencies that may arise during the term of a cabinet and which may push in the direction of additional expenditure, reductions in government revenue, or both. However, we still hypothesize that comprehensive coalition agreements reduce the (“negative”) effect of government fragmentation on spending:

H1

In the presence of a comprehensive coalition agreement, the impact of government fragmentation on government spending is reduced.

It should here be clarified that we do not expect just any kind of coalition agreement to function as a constraint on parties or ministers in a multiparty cabinet—the agreement has to be precise and broad enough (covering a broad range of issues), or “comprehensive”, in order for the agreement to have an offsetting effect on government fragmentation. Such agreements can largely confine governments to agreed projects and fix their budgets. Ideally, such forecasts are based on detailed planning and budgeting. Comprehensive agreements may also contain specifics about the extraction of additional resources for the government. In the presence of constitutional fiscal rules on government spending, such agreements between the coalition parties can help in achieving the preset targets. In the absence of such obligations, the agreement may function as partial substitute for fiscal discipline by preventing spending projects not explicitly agreed on and containing the costs of those that are included. Quite simply, the more detailed the policy agreements, the smaller the probability should be that ministers pursue polices not acceptable to the coalition partners (Müller and Meyer 2010a, b).Footnote 7 By committing to such programs, coalition parties take considerable risks as they set themselves up as targets in the case of unfulfilled promises. Considering the effort required and the associated risks, comprehensive coalition agreements are likely when at least one of the coalition partners does not want to rely on spontaneous coordination in the process of governing, preferring “contractual” obligations that all parties must observe (Müller and Strøm 2008). For other parties, consenting to such agreements may be more related to attaining office per se rather than fixing the government policy agenda ex ante.

Coalition agreements, hence, may (partly) solve the “common pool problem”, and here we can easily connect the “fiscal institutionalist” literature to the literature on coalition governance mechanisms since they are based on a similar argument: the PM and the cabinet have delegated powers (e.g., over spending) to individual ministers as department heads and may run into difficulties in controlling the behavior of these ministers. The main argument is that the coalition agreement constitutes an ex ante control mechanism which should, when specified in precise terms, put limits on ministers in terms of spending since the “contract” establishes what the ministers should do. For example, in the Netherlands, some agreements have been seen as “holy”, considerably diminishing the agenda-setting power of ministers (Timmermans and Andeweg 2000).

Coalition agreements, especially if public, employ several mechanisms that can reduce the moral hazard problem that is underlying coalition policy-making. Although not every policy detail can be fixed ex ante, they establish “reference points” about future policies, in particular with regard to those issues that are contested between the partners (Hart and Moore 2008). This is important, as unclearly stated policies tend to produce different expectations among the coalition partners about the course of the government. If such expectations are then not met, the short-changed party is likely to retaliate. As indicated, making the coalition agreements public introduces reputational concerns. In short, publicity of the deal makes it costlier for parties to renege on their concessions and, hence, more likely to implement what is in the contract. Finally, public coalition agreements potentially can also help coalition parties to resolve internal problems resulting from underdetermined expectations. They inform intra-party actors about the conditions of government participation and commit the party in its entirety, in particular if processed through more inclusive intra-party decision-making mechanisms.

Typically, coalition builders also are concerned to support their agreements with mechanisms of oversight and conflict management (Andeweg and Timmermans 2008; Müller and Meyer 2010b). Within the government institutions, these mechanisms include “watchdog” junior ministers who can “keep tabs” on the senior minister (see, e.g., Thies 2001; Müller and Strøm 2000; Verzichelli 2008; Lipsmeyer and Pierce 2011) and the use of parliamentary committees and questions placing “checks” on ministers (Martin and Vanberg 2011). Specific coalition institutions may also exist to evaluate policy proposals, table concerns, forge agreements and resolve conflicts (Müller and Strøm 2000; Andeweg and Timmermans 2008). Such mechanisms can complement each other and which one is chosen typically depends on the specific circumstances.

While we thus expect comprehensive coalition agreements potentially to be important for government policy, they are no panacea (Moury 2011; Timmermans 2006). Even when supported by the conditions detailed above, they remain incomplete contracts (Williamson 1979; Salanié 2005). Parties that write coalition contracts are aware that their foresight about how the economy and other factors will develop is less than perfect (Hayek 1945) and that not all contingencies can be addressed in the agreement. Still, they consider that having an agreement on the most likely scenario to be better than no agreement. They also know that coalition contracts are not self-enforcing nor can they be enforced by legal means. Rather, they need to be enforced by political means. While the presence of the conditions specified above make such political enforcement more likely, we can also identify conditions that make it less likely. We begin our discussion with the ideological spending priorities of government parties. Clearly, some parties will value government budgetary restraint less than others as a goal in its own right. All line ministers also have strong incentives for portfolio-specific spending regardless of their ideologies.Footnote 8 Portfolio allocation according to party policy saliency, a typical feature of coalition governments (see, e.g., Bäck et al. 2011), strengthens this tendency further.

Finally, we have to consider the institutional setting in which coalition parties interact. Institutions, such as cabinet members’ constitutional rights and government procedural rules, can create considerable power asymmetries between the cabinet parties. The classic source of such power asymmetries within the cabinet, of course, rests in the office of the Prime Minister, who not only appoints and dismisses cabinet members but may also have considerable agenda control and steering rights as well as substantial informational advantages (e.g., Bergman et al. 2003, pp. 179–194). Note that such an institutional setup in effect resembles the means of delegating budgetary veto power to one central actor, which fiscal institutionalists have discarded because coalition partners would not be willing to accept it. Incoming governments typically inherit such institutional rules.

Comprehensive coalition agreements are incomplete contracts that cannot be enforced through legal channels. We suggest that institutional power asymmetries potentially undermine the credibility of contractual commitments made by coalition parties, and thus the effects of a comprehensive coalition agreement may be conditional, with their effects constraining the effect of fragmentation on spending limited to situations in which the institutional powers of parties in cabinet are more symmetrically distributed. We therefore propose a second hypothesis:

H2

In institutional settings where power is symmetrically distributed among the parties in a coalition, i.e., when there is a weak PM, a comprehensive coalition agreement will reduce the effect of government fragmentation on spending.

The logic here is that, if one cabinet party has a major advantage in terms of policy verification and enforcement, the other parties may suspect that it will use those powers in a partisan manner to advance its goals. We need not think of such behavior as blunt violations of the coalition contractual commitments. Given the nature of coalition agreements as incomplete contracts and “reference points”, it may be more reasonable to think of violations of the coalition agreements’ spirit by one-sided interpretations of their words that systematically benefit one party over its partners. While the privileged party’s policy gains from each decision may not be large, their accumulated effects can be of considerable magnitude.

Under such conditions, the weaker government parties have little or no incentive to fulfil their part of the deal in terms of budgetary discipline. Even fiscally conservative parties will not want to let their portfolios and clienteles carry the entire burden of budgetary restraint, and spend-thrift parties will have another incentive to demand government spending. In coalitions with asymmetric institutional powers, the weaker coalition parties are thus likely to constitute a push-factor for government spending regardless of their ideological fiscal priorities.

In fact, not only may a comprehensive agreement be ineffective at reigning in the effect of government fragmentation on spending but it may in fact exacerbate the problem. A comprehensive coalition agreement ties coalition partners together more closely in the eyes of voters. Bringing home policy rewards may be the only way to maintain a party’s profile in a government headed by a PM from another party. This may play out in fighting a running battle over each government decision with budgetary implications, up to and including threats of leaving the coalition. This push-factor may be met by a pull-factor as the PM has the strongest personal incentive to keep the coalition together. Having achieved what is the apex of a political career, remaining in that office should take an important if not exclusive role in his or her incentive structure. Appeasing coalition partners and smoothening the running of government work may well be worth additional spending.

Take the four Danish cabinets headed by Prime Minister Paul Nyrup Rasmussen in the 1990s and early 2000s which all had comprehensive coalition agreements. Note also that the Danish Prime Minister enjoys considerable powers. The first of these cabinets resulted from the fall of the last cabinet under Conservative Prime Minister Poul Schlüter who was forced out of office over the Tamil affair by two of the smaller non-socialist cabinet parties, which then joined forces with the Social Democrats and left-liberal Radicals. Rasmussen’s center-left four-party coalition inherited the 1993 budget from its Conservative-led predecessor but made significant expansions to fight unemployment. However, this already costly Social Democratic project needed to be bought-off with concessions to the new partners, making the budget even more expansionary. In the words of the Economist Intelligence Unit’s report (1993.08, p. 10), “it took much skill to put together proposals that satisfied the two small centrist parties in government, the Centre Democrats and the Christian People’s Party, which have traditionally opposed anything likely to increase the tax burden on business or to fuel public spending”. In a similar vein, the leader of the Radical Liberal Party, Marianne Jelved, praised Rasmussen “for showing the will and ability to take the smaller parties’ views into consideration”. The situation was similar in the second Rasmussen cabinet that included only three parties but held a minority position, thus forcing the PM to seek consensus first within the cabinet and then beyond. Government spending was significantly lower under the two subsequent two-party minority cabinets of PM Rasmussen of the Social Democrats and Radicals. Not only did the economy improve considerably and could the government choose to make the most favourable deal available, either with the right or left opposition (Laver and Schofield 1990), but the Prime Minister also benefited from a reduced need for internal coordination and support-buying within the cabinet. This dynamic suggests a striking conditional final hypothesis to test:

H3

In institutional settings where power is asymmetrically distributed among the parties in a coalition, i.e., when the PM is strong, a comprehensive coalition agreement will increase the effect of government fragmentation on spending.

2.4 How do our hypotheses relate to the fiscal institutionalist literature’s predictions?

Before turning to evaluating our hypotheses, we should be completely clear about how our hypotheses relate to the previous literature focusing on similar explanatory features. As described above, the “fiscal institutionalist” literature has identified two approaches to curbing government spending: (1) the “delegation approach”, which suggests that the common pool problem may be reduced by delegating veto rights to offices, such as the Minister of Finance, or the PM, and (2) the “contract approach”, which suggests that coalitions aim at negotiating overall spending targets and rules at the beginning of the term and that each minister works under preset spending limits. However, most scholars suggest that the delegation approach is a remedy only for single-party cabinets since in coalitions no single office holder enjoys the trust of all government parties (Hallerberg et al. 2007, 2009; de Haan et al. 2013).

We agree with these scholars and, since we are here focusing on the common pool problem arising within coalitions where ministers are appointed from different parties (i.e., coalitions) and have different spending priorities, our explanation lies closer to the so-called “contract approach”. Our hypothesis (H1) about the role of comprehensive coalition agreements relies on mechanisms very similar to the ones proposed by scholars focusing on the “contract approach”, but, rather than concentrating on specific spending limits, our explanation instead zooms in on the fact that comprehensive agreements “bind” the parties in more specific ways, and constitute an ex ante control mechanism that should, when specified in precise terms, put limits on ministers with respect to spending since the “contract” establishes what the ministers should do in terms of policies to be implemented.

Since the “delegation approach” also stresses the role of strong individual actors within the governments, for example PMs, which we likewise do, we should also make clear how our argument about the roles of PMs differ from this approach. According to the “delegation approach”, strong PMs may be able to solve common pool problems (e.g., in less ideologically diverse coalitions), whereas we argue here that strong PMs shift the “balance of power” within the cabinet, creating a situation where power is asymmetrically distributed—hence, we suggest that strong PMs are in our theory “detrimental” for the functioning of the so-called “contract approach” in coalition governments. Hence, in a way, and described in a simplified manner, we are suggesting that a combination of a “delegation approach” and a “contract approach” should be negative for coalition governments in solving the common pool problem, and may result in more spending than if just a “contract approach” is used.Footnote 9

3 Data and methods

3.1 Data sources, country coverage and methodological issues

This section describes all of the variables included in our analyses and identifies our main data sources. In Appendix Table 2, we also include a more detailed description of all variables and data sources. We combine data from two main sources. First, we use Bawn and Rosenbluth’s (2006) dataset, generously provided by the authors, which covers 17 Western European countries from 1970 to 1998, and draws on economic data from OECD sources. It defines a number of political variables drawn from Warwick’s (1999) dataset on government survival and the Comparative Manifestos Project (Budge et al. 2001).

Second, to measure comprehensive coalition agreements, and some additional political variables, we draw on the Comparative Parliamentary Democracy Data Archive (Strøm et al. 2008), which covers all cabinets formed in 17 Western European countries from post-WWII through 1999. Hence, our country-time coverage is the 17 Western European countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxemburg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom), covered, in most cases, between 1970 and 1998. This period is one wherein international influences on domestic budget policies were mostly indirect, mediated by economic factors and, hence, national governments were relatively free in their choices. The Amsterdam Treaty of 1997 set in a process of establishing increasingly tight European constraints on national budgeting. Analyzing this period allows us to better focus on the domestic factors that determine the relationship between multiparty government and fiscal policy. The unit of analysis is the country-year and, following Bawn and Rosenbluth (2006), for variables that change with cabinets, we have created a weighted average based on the length of time that each cabinet is in office in each year.

Before turning to describing our variables, we should discuss potential problems with endogeneity of coalition contracts to unobserved variables. This problem has long been recognized in the literature on the policy effects of fiscal rules. In that respect, Poterba (1997, p. 58) refers to Riker (1980), who “argues that essentially all political institutions reflect the ‘congealed preferences’ of the electorate. In this view, institutions that no longer suit a majority of the electorate will be overturned, and the institutional structure of a nation or state contains no information other than some aggregation of information on current voter preferences.” Poterba (1997, p. 59) goes on to suggest that counterarguments to such a view of endogeneity problems emphasize the difficulty in changing institutions, and the costs of amending fiscal rules. He describes two approaches to try to solve the problem of endogenous fiscal institutions: (1) one strategy is to control for some measure of (voter) preferences, for example, by including controls measuring party positions, and (2) another strategy is to use variables that affect budget rules but not fiscal policy as instrumental variables. However, Poterba (1997) suggests that the latter approach typically is problematic to implement owing to the difficulty of finding valid instruments.

As we are here focusing on the “comprehensiveness” of coalition agreements rather than whether or not they include fiscal rules, we believe that the risk is small that some underlying preferences explain both whether a comprehensive agreement is implemented by a government and the economic policy-making of that government. However, in our multivariate models, we do include a “preference” measure, specifying the left–right ideology of the government, which should, at least in some sense, account for the preferences of the electorate (see below). Concluding a chapter explaining the presence of formal coalition agreements, Müller and Strøm (2008, p. 196) suggest that “once a certain set of [coalition] governance institutions have evolved in a particular country, these institutions tend to get replicated in subsequent coalitions”. This view points to the conclusion that coalition contracts are relatively stable institutional features. Demanding changes in coalition negotiations to such time-honored rules might raise suspicion among the coalition partners. As a consequence, such rules are difficult and costly to change, suggesting that endogeneity issues should not be an important problem here.

3.2 Operationalization of government spending and explanatory variables

Our dependent variable is total government spending. Measuring government spending is relatively straightforward, and we here follow Bawn and Rosenbluth (2006) in including a government spending variable, which measures the “overall government expenditure in a given year, measured as a fraction of GDP” (Bawn and Rosenbluth 2006, p. 256).Footnote 10

One of our main explanatory variables is the number of parties in government. This variable is taken from the Bawn and Rosenbluth (2006) dataset, which draws on information from Warwick (1999) and is a straightforward count of the number of parties in government. To solve the problem that governments may change during a year (as the analysis is performed on an annual basis), the variable is weighted by the number of days in power, resulting in non-discrete values for cases in which the number of parties in government changes during the year.

In moving beyond Bawn and Rosenbluth, we focus on two factors: coalition agreements and PM powers. As described by Müller and Strøm (2008, pp. 174–176), coalition agreements differ in their completeness: “some coalitions are based on a comprehensive policy programme, in which the participants commit themselves to a broad range of policy initiatives”, whereas other programs include commitments only on a few selected issues. To gauge whether there was a comprehensive agreement in each of the cabinets in the 17 Western European countries, we rely on a variable drawn from the Comparative Parliamentary Data Archive, which is based on a content analysis of coalition agreements by country experts. The agreements were classified according to a four-category ordinal coding scheme: (1) no policy agreement, (2) agreement on a few selected policies only, (3) agreement on a variety of issues, and (4) agreement on a comprehensive policy program. Our main results rely on a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not a comprehensive policy program was in place (which existed in 43 % of the country-years in our sample). Alternative operationalizations lead to similar results, as shown in the appendix.

Assessing PM powers—and specifically the powers that might weaken the credibility of coalition agreements—is not a trivial matter. It is important for our purposes to focus on institutional measures of PM powers, given our theoretical argument and the fact that reputational measures of PM power are frequently conditional on other contextual factors, such as whether the PM was leading a single-party or a coalition government (cf. O’Malley 2007). As the institutional powers of the PM change rarely, we are forced to rely on measures of PM strength that are not time-varying.Footnote 11

In general, however, various PM powers typically are correlated: institutionally strong PMs usually have a full range of agenda control in cabinet, appointment and dismissal powers, administrative capacity, and so forth, whereas weak PMs fail to have most of these powers (Bergman et al. 2003). Given the correlation across indicators, most markers of particular PM powers do not simply capture just one specific power, but are also rough proxies for other powers. The primary measure we rely on is taken from Bergman et al. (2003): it is a dichotomous indicator as to whether the PM has the (exclusive) ability to control the cabinet’s agenda. This power seems central to intra-coalition relationships, and is also a power that is both highly correlated with most other PM powers. The measure divides our sample roughly in half, with PMs in Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom coded as having agenda control, whereas PMs in Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Greece, Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden are coded as not having agenda control. Relying on alternative cross-sectional measures of PM powers, including dichotomous measures, such as whether the PM has unilateral ability to appoint and dismiss cabinet ministers, explicit authority to coordinate inter-ministerial concerns, or even the trichotomous coding found in King (1994), lead to similar results, as reported in the appendix.

Following Bawn and Rosenbluth (2006), we include a range of political and economic control variables, and we here adopt their approach, and include control variables for the effective number of parties in the legislature, ENP (legislative fragmentation), government ideology (left–right scores drawn from comparative manifestos data), caretaker governments, per capita GDP in billions of US dollars, unemployment (unemployed as a percentage of the total labor force), the dependency ratio (fraction of population over age 64 and under age 15), and trade openness (imports + exports, divided by GDP). Finally, we control for budgetary institutions, using data originally collected by Hallerberg et al. (2009), also included in the analyses of Martin and Vanberg (2013). Descriptive statistics for our sample are reported in the appendix (see Appendix Tables 3, 4).

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Graphical presentation of the relationships between spending and explanatory features

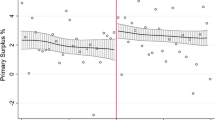

Central to our argument is the idea that different factors may condition the long-established effect of the number of parties in government on government spending. We begin our analyses by reporting our data graphically, broken down by the key conditions that we have identified.Footnote 12 The first panel of Fig. 1 focuses on the cases in which no comprehensive policy agreement was in place between coalition partners, showing the relationship between the number of parties in a coalition government and government spending in cases of strong PMs (circles) and weak PMs (triangles). While government spending is on average about one point lower (as a percentage of GDP) in the countries with a weak PM, the estimated effect of increasing the number of parties on government spending in both cases is nearly identical, and comparable to previous estimates of the effect of the number of parties in government on government spending.Footnote 13

The second panel focuses on the relationship between government spending and the number of parties when a comprehensive coalition agreement exists, showing results that are consistent with our second hypothesis. When a coalition agreement is combined with a weak PM, essentially no relationship exists between the number of parties in government and government spending. However, a coalition agreement combined with a strong PM is associated with a marked rise in government spending as the number of parties in government increases—the estimated effect of each additional party in this case is nearly five times larger than the pooled relationship between government fragmentation and spending in our sample. Thus, at a descriptive level, there appears to be some support for both of our conditional hypotheses.

4.2 Multivariate analyses of government spending, coalition agreements and PM power

Of course, the results shown in Fig. 1 simply highlight our central finding graphically. Statistical analyses are needed to show that the results are significant and robust to alternative explanations. Our statistical analyses replicate and extend Bawn and Rosenbluth’s (2006) work on the effects of coalition cabinets on government outlays. Models 1 and 4 in Table 1 report the main results of interest from Bawn and Rosenbluth’s study: increasing the number of parties in government significantly increases government outlays in the subsequent year. Model 1 reports an OLS regression model with panel corrected standard errors (Beck and Katz 1995); the effect is estimated at roughly 0.3 % of GDP.Footnote 14 In Model 4, which includes country fixed effects, the estimated coefficient is larger, at roughly 0.55 % of GDP.Footnote 15 Complete models reporting all control variables, as well as additional robustness models testing additional specifications and alternative measures, can be found in the appendix (Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

In Models 2 (random effects) and 5 (fixed effects), we enter the indicator for comprehensive coalition agreements and its interaction with the number of cabinet parties to test our first hypothesis. The results of neither model provide support for Hypothesis 1. In fact, both models suggest that the marginal effect of each additional party in government on spending is slightly greater when a comprehensive coalition agreement is in place. While these models fail to find significant support for our first hypothesis, the lack of support may, however, stem from the possibility that agreements vary in their effectiveness depending on the institutional environment. If, as suggested in our discussion of Hypotheses 2 and 3, the effect of coalition agreements in mitigating the common pool problem is conditional on PM powers, with the effect going in opposite directions in countries with weak and strong PMs, it should be unsurprising to find no support for Hypothesis 1. We test this possibility using a three-way interaction between changes in the number of parties, types of coalition agreements, and PM powers in Models 3 and 6 in Table 1.

Although the coefficient on the triple interaction term is significant in the predicted direction in Models 3 and 6 of Table 1, it is difficult to interpret the overall magnitude and statistical significance without further calculation. Figure 2 demonstrates graphically the tests of Hypothesis 2 from Table 1, showing the results of the marginal effects of the number of parties when PM powers are weak. The results for Models 3 and 6 are consistent with Hypothesis 2: the marginal effect of the number of parties on spending is positive and significant when no comprehensive coalition agreement is in place, but insignificant in the presence of such an agreement. However, this difference in the marginal effect of the number of parties is not statistically significant at conventional levels in most of our models.Footnote 16

Figure 3 reports comparable graphical interpretations of the marginal effects of the number of parties in the presence of a strong PM. The support for Hypothesis 3 is strong and robust in both the random effects and fixed effects models: the marginal effect of the number of parties on spending for governments with strong PMs and a comprehensive coalition agreement typically is four times larger than when no comprehensive agreement exists. One note of caution is the larger confidence interval associated with the strong PM, comprehensive agreement combination, which is largely attributable to the fact that that combination is present in only 51 observations, whereas each of the other combinations in our sample has more than 100 observations.Footnote 17 However, even with the smaller sample size for this combination, the difference in estimated effect is striking, being both statistically significant and consistent across all of our models.Footnote 18

Overall, while we do not find support for our Hypothesis 1, and thus no support for an overall mitigating effect of comprehensive coalition agreements on the common pool problem in coalition government’s fiscal policy, our results do find support for conditional effects of comprehensive coalition agreements on fiscal policy. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, when PMs are weak and in the absence of a comprehensive coalition agreement, we find a statistically significant effect of the number of parties on government spending, but no significant effect of the number of parties on spending when such an agreement exists. Our empirical results find even stronger support for Hypothesis 3, which suggests that the combination of a strong PM and a comprehensive coalition agreement may perversely exacerbate the common pool problem seen in cabinet governance. Overall, these results suggest that mechanisms for managing coalition bargaining may have quite different effects when one party has disproportionate institutional power .

5 Conclusion

This paper makes two contributions to the study of multiparty government. The emerging literature on coalition governance has hardly addressed the effects of coalition governance mechanisms on policy outcomes. In this paper, we aim at making a contribution towards that research agenda by addressing the role of comprehensive coalition agreements. And while the literature on coalition governance has shown how existing institutions—such as parliamentary committees and junior ministers (Martin and Vanberg 2011; Thies 2001)—can be used for the purpose of coalition governance, the present paper shows that another institution—a powerful Prime Minister—may pose a severe challenge for interparty cooperation in cabinet decision-making. The aim of this paper has been to evaluate the role in economic policy-making of policy contracts written by coalition parties at the time of government formation. Do comprehensive policy agreements mitigate potential problems that may occur in multiparty governments? We have here developed a hypothesis that policy contracts function as solutions to delegation problems in coalitions only in certain institutional settings, where PM power is weak.

Our results, when focusing on the spending behavior of cabinets formed in 17 Western European countries (1970–1998), support the general idea that the drafting of coalition agreements matter for the performance of multiparty cabinets in economic policy-making. We find support for our newly formulated conditional hypothesis and show that coalition agreements reduce the negative effect of government fragmentation on spending only in those contexts where the PM is weak. However, our results suggest the opposite effect of comprehensive coalition agreements when the PM is strong. While the results suggest that coalition agreements may help solve the common pool problems in coalition governments in certain circumstances, their effect in other circumstances may perversely exacerbate common pool problems.

We suggest that future work should also look at the role of coalition agreements when predicting actual reform behavior, not just spending levels. This would in turn allow scholars to address problems of “veto player deadlock” and test hypotheses about the role of veto players more directly (Tsebelis 2002). However, to analyze the role of coalition agreements when explaining reform behavior, we need “better” data on actual economic reform measures. We suggest that it would be ideal to rely on more direct measures of actual reforms rather than the indirect measures used in many previous studies.

Another potential avenue for future research is to investigate the role of alternative so-called “coalition governance mechanisms”, for example, the appointment of junior ministers (see, e.g., Lipsmeyer and Pierce 2011; Strøm et al. 2010; Thies 2001). One control mechanism, labeled “watchdog junior ministers”, suggests that parties in a coalition appoint a junior minister from another party to “keep tabs” on the senior minister. Hence, agency loss is here expected to be reduced by having a “watchdog” in the department, who could, for example, inform the PM about irregular spending behavior, thereby solving potential common pool problems in multiparty cabinets. Another feature worth taking a look at is a powerful coalition committee that brings together the most important leaders of all coalition parties as something like “equals”. Whatever the committee would decide, would then be implemented though the intra-party chain of command from the party leader to ministers or MPs (Andeweg and Timmermans 2008).

Another avenue of research focuses on other government features to qualify the claim that multiparty governments are less able to deal with economic policy-making and looks instead at the ability of coalition partners to make credible commitments. Bäck and Lindvall (2015) suggest that only specific types of multiparty governments are prone to produce more public debt, namely, those coalitions that are unable to resolve inter-temporal bargaining problems. Coalitions that are able to solve such problems and are able to commit to fiscal reform are not likely to perform worse than single-party governments. The authors show that coalition governments with high “commitment potential” do not accumulate more debt than do single-party governments. Future work should consider potential interactions between coalition governance mechanisms and the degree of commitment potential.

We also believe that future research on the role of coalition agreements in economic policy-making could gain from a more precise classification of coalition agreements. More work should be done coding the particular policy issues that are covered in the “contract” and, following the “fiscal institutionalist” literature, more work should be done to code whether more specific information on fiscal rules or targets are included in the coalition agreements presented by European governments. This should allow us to understand even better the role of coalition agreements in solving common pool problems, and how they might influence decision-making in multiparty governments. In addition, more work should be done explaining why some coalitions implement more comprehensive agreements whereas others do not. To date, very little work has focused on explaining why coalitions choose different types of coalition agreements, even though important work has been done by Müller and Strøm (2008) explaining the presence of formal coalition agreements. Predicting coalition agreements, institutional features, situational features (e.g., time pressure), and preferences of coalition partners (e.g., preference divergence and policy saliency) are important features to take into account.

The present paper has taken seriously the concerns about governing in multiparty coalitions that have been present ever since political scientists started addressing issues of government under proportional electoral laws. More specifically, the article has addressed the most recent incarnation of such concerns relating to economic efficiency. While the underlying problems are real, we argue that they are best seen as a challenge to coalition architects rather than a fate that inevitably ties coalition economic policy-making to inferior performance. Our analyses suggest that careful design of coalition governance mechanisms can contain problems of inter-party cooperation and improve policy output.

Notes

Fundamentally, the previous literature has been limited when it comes to empirically studying the role of government institutions when trying to explain economic outcomes. Most empirical studies focus on the effect of electoral systems (see, e.g., Persson and Tabellini 2003) instead of governmental characteristics. The studies that do focus on the role of government features have been based on rather crude variable specifications, for example, focusing only on the number of parties in cabinet (Hallerberg and von Hagen 1999; Bawn and Rosenbluth 2006), a simple dummy specifying if the government was a coalition (Persson et al. 2007), or measuring minority status (Edin and Ohlsson 1991; Hallerberg and von Hagen 1999). Some studies have also measured government “strength” by combining several features into an index (Roubini and Sachs 1989; Borrelli and Royed 1995).

Another proposed mechanism draws on Tsebelis’s veto player theory and in the government context relates to the number and divergence of the cabinet parties. Simplifying the argument, single-party governments have only one veto player, while coalition governments have as many as there are cabinet parties (Tsebelis 2002). Given governments’ constant need to adapt existing policies to new challenges, coalitions should produce inferior budgetary policies and the outcome should worsen with the number of parties that need to be accommodated. In this article, we focus on “common pool problems” and how they can be solved within coalition governments.

In this paper, we focus on the literature that refers to government fragmentation in terms of the number of parties included in the government. There is, however, also a smaller literature that focuses instead on the effect of the number of cabinet ministers on budget deficits and expenditures (see, e.g., Wehner 2010, 2011 for an overview of this literature and an evaluation of this hypothesis).

A limited role of the Minister of Finance in coalition governments is supported by Goodhart (2013). She researches the extent to which the partisan affiliation of the Minister of Finance shapes the economic policy priorities of coalition governments. Focusing on partisan changes in the positions of Minister of Finance and PM, she finds the latter (who usually comes from the strongest cabinet party) and the real economy more important.

De Haan et al. (2013) show that “budgetary institutions, no matter whether they are based on a strong minister of finance or fiscal contracts, become significant in case of strong ideological fragmentation, thereby mitigating the impact of political fragmentation”. No such mitigating effect is found for the number of governing parties.

In this paper, we do not address the question why some coalitions have comprehensive agreements and others only minimal or no agreements (see Müller and Strøm 2008). While the institutional setting is likely to influence that choice, it is by far not the only factor that is likely to matter. For instance, a government formation may occur under time pressure, simply leaving few opportunities for working out an elaborated contract. In addition, the time remaining before the next election may be too short to make it worth investing in a comprehensive agreement. Other factors relate to the actors involved in the coalition deal. Large preference divergences between the coalition parties may foster comprehensive agreements. Finally, intra-party factors may come into play. Parties with inclusive methods for deciding over government participation may require a document that demonstrates the achievements of the negotiators, while parties with a more autonomous leadership may be able to do without (Marsh and Mitchell 1999).

Our reasoning is compatible with the argument developed by Falcó-Gimeno (2014) that coalitions characterized by “preference tangentiality”—assigning different saliencies to different policies and portfolios—are less likely to adopt coalition governance mechanisms such as comprehensive coalition agreements and “watchdog” junior ministers. While preference tangentiality should weaken the ideological incentives to invest in such mechanisms, it should at the same time strengthen the dangers that arise from portfolio-related budgetary claims and thus render such investments worthwhile.

As described by Hallerberg and von Hagen (1999), countries that typically have single-party or ideologically cohesive governments are more likely to have adopted a “delegation approach”, and that it may be difficult to quickly alter this approach (e.g., if the PM’s powers are constitutionally defined). Hence, when an ideologically diverse coalition forms in such a country, in need of alternative control mechanisms, it may be that the country ends up with a situation wherein both approaches are used (i.e., that both “delegation” and “contract” mechanisms are used to curb spending).

Bawn and Rosenbluth (2006, p. 256) measure spending, or the “size of the public sector”, as “Total Government Spending as a Fraction of GDP” (CN056OTT), and we rely on their expenditure data, which are based on the OECD’s Quarterly National Accounts Database. As described by the OECD (https://data.oecd.org/gga/general-government-spending.htm#indicator-chart), “General government spending generally consists of central, state and local governments, and social security funds”.

The resources and staff in many PM offices have been strengthened over time in Western Europe, but the fundamental institutional powers (which are more central to our theory) rarely have been altered significantly (e.g., Poguntke and Webb 2005).

Reporting the raw data graphically allows us to show how our results are driven by the variation within coalition governments (as suggested by our theory), rather than simply coalition versus single-party governments, and that no major non-linearities in the relationship suggest that the linear regression results we report are mis-specified.

The main specifications we report are the two most common model specifications for our data: (1) pooled OLS models with random effects and panel-corrected standard errors, and (2) models with country fixed effects. Our results are also robust to the inclusion of time trends, year dummies and alternative approaches to handling autocorrelation and temporal dynamics, as reported in the Appendix.

Esarey and Sumner (2015) critically evaluate the now standard practice of comparing overlapping confidence intervals for testing the effects of interactions. In a situation such as our Hypothesis 2, where we theorize one marginal effect to be significant in a specified direction and another specific coefficient to be insignificant, their simulations suggest that confidence intervals based on a t-value of ~1.1 more accurately provides the equivalent of a standard one-tailed 95 % confidence level hypothesis test. However, the differences between the standard practice of reporting 90 % confidence intervals (t = 1.28) is relatively minor, and does not affect the interpretation of our results, so we use the more conservative standard practice, even though doing so may understate slightly the significance of the difference between the two marginal effects.

Our dataset comprises 102 observations of weak PMs with comprehensive coalition agreements, 114 observations of weak PMs without comprehensive agreements and 139 observations of strong PMs without comprehensive coalition agreements.

We report a number of additional models in the appendix, including models showing that our results are robust to controlling for budgetary rules (Table 6), as is done in Martin and Vanberg (2013), who also replicate and extend Bawn and Rosenbluth (2006), building on the arguments and measures of Hallerberg et al. (2009).

References

Alesina, A. F., & Perotti, R. (1999). Budget deficits and budget institutions. NBER Chapters. In Fiscal institutions and fiscal performance (pp. 13–36). Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Andeweg, R. B., & Timmermans, A. (2008). Conflict management in coalition government. In W. C. Müller & K. Strøm (Eds.), Coalition governments in western democracies (pp. 269–300). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bäck, H., Debus, M., & Dumont, P. (2011). Who gets what in coalition governments? Predictors of portfolio allocation in parliamentary democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 50(4), 441–478.

Bäck, H., & Lindvall, J. (2015). Commitment problems in coalitions: A new look at the fiscal policies of multiparty governments. Political Science Research and Methods, 3(1), 53–72.

Bawn, K., & Rosenbluth, F. (2006). Short versus long coalitions: Electoral accountability and the size of the public sector. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 251–265.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647.

Bergman, T., Müller, W. C., Strøm, K., & Blomgren, M. (2003). Democratic delegation and accountability: Cross national patterns. In K. Strøm, W. C. Müller, T. & Bergman (Eds.), Delegation and accountability in parliamentary democracies (pp. 109–220). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blais, A., Kim, J., & Foucault, M. (2010). Public spending, public deficits and government coalitions. Political Studies, 58(5), 829–846.

Borrelli, S. A., & Royed, T. J. (1995). Government “strength” and budget deficits in advanced democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 28(2), 225–260.

Bryce, J. (1921). Modern democracies. London: Macmillan.

Budge, I., Klingemann H.-D., Volkens, A., Bara, J., & Tanenbaum, E. (2001). Mapping policy preferences: Estimates for parties, electors, and governments 1945–1998. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

De Haan, J., Jong-A-Pin, R., & Miearau, J. O. (2013). Do budgetary institutions mitigate the common pool problem? New empirical evidence for the EU. Public Choice, 156(3), 423–441.

Economist Intelligence Unit. (1993). Country report. Denmark, Iceland (3 rd quarter 1993). London: Economist Intelligence Unit.

Edin, P., & H. Ohlsson. (1991). Political determinants of budget deficits: Coalition effects versus minority effects. European Economic Review, 35, 1597–1603.

Esarey, J., & Sumner, J. L. (2015). Marginal effects in interaction models: Determining and controlling the false positive rate. Houston: Manuscript, Rice University.

Falcó-Gimeno, A. (2014). The use of control mechanisms in coalition governments: The role of preference tangentiality and repeated interactions. Party Politics, 20(3), 341–356.

Goodhart, L. (2013). Who decides? Coalition governance and ministerial discretion. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 8(3), 205–237.

Hallerberg, M. (2004). Domestic budgets in a united Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Hallerberg, M., & Basinger, S. (1998). Internationalization and changes in tax policy in OECD countries: The importance of domestic veto players. Comparative Political Studies, 31(3), 321–352.

Hallerberg, M., Strauch, R. R., & von Hagen, J. (2007). The design of fiscal rules and forms of governance in European Union countries. European Journal of Political Economy, 23(2), 338–359.

Hallerberg, M., Strauch, R. R., & von Hagen, J. (2009). Fiscal governance in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hallerberg, M., & von Hagen, J. (1999). Electoral institutions, cabinet negotiations, and budget deficits in the European Union. In J. Poterba & J. von Hagen (Eds.), Fiscal institutions and fiscal performance (pp. 214–219). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hart, O., & Moore, J. (2008). Contracts as reference points. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(1), 1–48.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. American Economic Review, 35(4), 519–530.

King, M. (1994). Monetary policy in the UK. Fiscal Studies, 15, 109–128.

Laver, M. & Schofield, N. (1990). Multiparty Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Laver, M., & Shepsle, K. A. (1996). Making and breaking governments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lipsmeyer, C., & Pierce, H. N. (2011). The eyes that bind: Junior ministers as oversight mechanisms in coalition governments. Journal of Politics, 73(4), 1152–1164.

Lowell, A. L. (1896). Governments and parties in continental Europe. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin.

Marsh, M., & Mitchell, P. (1999). Office, votes, and then policy: Hard choices for political parties in the Republic of Ireland 1981–1992. In W. C. Müller & K. Strøm (Eds.), Policy, office, or votes? How political parties in Western Europe make hard decisions (pp. 36–62). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Martin, L. W., & Vanberg, Gg. (2011). Parliaments and coalitions. The role of legislative institutions in multiparty governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Martin, L., & Vanberg, G. (2013). Multiparty government, fiscal institutions, and public spending. Journal of Politics, 75(4), 953–967.

Moury, C. (2011). Coalition agreement and party mandate: How coalition agreements constrain the ministers. Party Politics, 17(3), 385–404.

Müller, W. C., & Meyer, T. M. (2010a). Meeting the challenges of representation and accountability in multiparty governments. West European Politics, 33(4), 1065–1092.

Müller, W. C., & Meyer, T. M. (2010b). Mutual veto? How coalitions work. In T. König, G. Tsebelis, & M. Debus (Eds.), Reform processes and policy change: How do veto players determine decision-making in modern democracies (pp. 99–124). New York: Springer.

Müller, W. C., & Strøm, K. (Eds.). (2000). Coalition governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Müller, W. C., & Strøm, K. (2008). Coalition agreements and cabinet governance. In K. Strøm, W. C. Müller, & T. Bergman (Eds.), Cabinet governance: Bargaining and the cycle of democratic politics (pp. 159–199). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Malley, E. (2007). The power of prime ministers: Results of an expert survey. International Political Science Review, 28(1), 7–27.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effect of constitutions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2006). Electoral systems and economic policy. In B. R. Weingast & D. A. Wittman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political economy (pp. 723–738). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Persson, T., Roland, G., & Tabellini, G. (2003). How do electoral rules shape party structures, government coalitions and economic policies. Mimeo: Bocconi University.

Persson, T., Roland, G., & Tabellini, G. (2007). Electoral rules and government spending in parliamentary democracies. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 2(2), 155–188.

Poguntke, T., & Webb, P. (Eds.). (2005). The presidentialization of politics: A comparative study of modern democracies (pp. 1–25). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Poterba, J. M. (1997). Do budget rules work? In A. J. Auerbach (Ed.), Fiscal policy. Lessons from economics research. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Riker, W. (1980). Liberalism versus populism. San Francisco: Freeman.

Roubini, N., & Sachs, T. D. (1989). Government spending and budget deficits in the industrialized countries. Economic Policy, 4(8), 99–132.

Salanié, B. (2005). The economics of contracts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Strøm, K. (1998). Institutions and strategy in parliamentary democracy: A review article. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 23(1), 127–143.

Strøm, K., Müller, W. C., & Bergman, T. (Eds.). (2008). Cabinets and coalition bargaining: The democratic life cycle in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Strøm, K., Müller, W. C., & Smith, D. M. (2010). Parliamentary control of coalition governments. Annual Review of Political Science, 13, 517–535.

Tavits, M. (2007). Clarity of responsibility and corruption. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 218–229.

Thies, M. F. (2001). Keeping tabs on partners: The logic of delegation in coalition governments. American Journal of Political Science, 45(3), 580–598.

Timmermans, A. (2006). Standing apart and sitting together: Enforcing coalition agreements in multiparty systems. European Journal of Political Research, 45(2), 263–283.

Timmermans, A., & Andeweg, R. B. (2000). The Netherlands: Still the politics of accommodation? In W. C. Müller, & K. Strøm (Eds.), Coalition Governments in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tsebelis, G. (2002). Veto players: How political institutions work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Verzichelli, L. (2008). Portfolio allocation. In K. Strom, W. C. Müller & T. Bergman (Eds.) Cabinets and Coalition Bargaining: the Democratic Life Cycle in Western Europe.) Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Volkering, B. & de Haan, J. (2001). Fragmented government effects on fiscal policy: New evidence. Public Choice, 109(3), 221–242.

Von Hagen, J., & Harden, I. J. (1995). Budget processes and commitment to fiscal discipline. European Economic Review, 39(3–4), 771–779.

Warwick, P. V. (1999). Ministerial autonomy or ministerial accommodation? Contested bases of government survival in parliamentary democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 29(2), 369–394.

Wehner, J. (2010). Cabinet structure and fiscal policy outcomes. European Journal of Political Research, 49(5), 631–653.

Wehner, J. (2011). Legislatures and the budget process: the myth of fiscal control. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Williamson, O. E. (1979). Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. Journal of Law and Economics, 22(2), 233–261.

Acknowledgment

This research was carried out under the auspices of the SFB ‘Political Economy of Reforms’ (SFB 884: C1) financed by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bäck, H., Müller, W.C. & Nyblade, B. Multiparty government and economic policy-making. Public Choice 170, 33–62 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0373-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-016-0373-0