Abstract

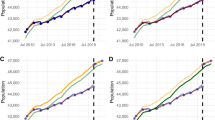

Policymakers and market analysts have long been interested in future trends of households. Among household projection methods, the ProFamy extended cohortcomponent method, as one alternative to the traditional headship-rate method, has recently been extended to the subnational levels. This paper illustrates the application of the ProFamy method at the county level by projecting household types, sizes, and elderly living arrangements for six counties of Southern California from 2010 to 2040, including Imperial, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Ventura.Using this specific case, this paper introduces the rationales and procedure of the county-level application of the ProFamy method. The validation test for the ProFamy to project the 2010 population and households using the 2000 census data support the use of the ProFamy at the county level. And the ProFamy method also yields satisfactory results in comparison with the projections of headship-rate methods. The ProFamy forecasts on the six county of Southern California provide detailed information on the county-level trends of households and elderly living arrangement in this region, which are valuable information for the local planning agency but usually beyond the capacity of the traditional methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The ProFamy research group is developing a R program (as part of ProFamy user-friendly & free software Web-online new version) for estimating the sex-age-specific standard schedules of the occurrence/exposure (o/e) rates of marriage/union formation and dissolutions, and the parity-age-specific o/e rates of marital and non-marital fertility. The ProFamy user-friendly & free software Web-online new version including the R program for estimating the sex-age-specific o/e rates will be released at the International Conference and Training Workshop on Household and Living Arrangement Projections for Informed Decision-Making, May 9–11, 2019, Beijing, China.

References

Abrahamse, W., Steg, L., Vlek, C., & Rothengatter, T. (2005). A review of intervention studies aimed at household energy conservation. Journal of Environmental Psychology,25, 273–291.

Allison, P. O. (1995). Survival analysis using the SAS-system: A practical guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Bell, M. & J. Cooper. (1990). Household forecasting: Replacing the headship rate model. Paper Presented at the Fifth National Conference, Australian Population Association, Melbourne.

Berard-Chagnon, J. (2015). Using tax data to estimate the number of families and households in Canada. In N. N. Hoque & L. B. Potter (Eds.). Emerging techniques in applied demography (Pp. 137–153). Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

Bradbury, M., Peterson, M. N., & Liu, J. (2014). Long-term dynamics of household size and their environmental implications. Population and Environment,36(1), 73–84.

Budlender, D. (2003). The debate about household headship. Social Dynamics,29(2), 48–72.

Burch, T. K., & Matthews, B. J. (1987). Household formation in developed societies. Population and Development Review,13(3), 495–511.

Casey, T. & Maldonado, L. (2012). Worst off–single-parent families in the United States. A cross-national comparison of single parenthood in the US and sixteen other high-income countries. New York: Legal Momentum, the Women’s Legal Defense and Education Fund.

Chappell, N. L. (1991). Living arrangement and sources of care giving. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences,46(1), 1–8.

Christiansen, S. G., & Keilman, N. (2013). Probabilistic household forecasts based on register data—The Case of Denmark and Finland. Demographic Research,28, 1263–1302.

Cline, M.E. (2017). Projected population of the state of North Carolina and North Carolina Counties by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin for July 1, 2017 through July 1, 2037. Retrieved from https://files.nc.gov/ncosbm/demog/county-projections-methodology.pdf.

Coale, A.J. (1984). Life table construction on the basis of two enumerations of a closed population. Population Index, 50, 193–213.

Coale, A.J. (1985). An extension and simplification of a new synthesis of age structure and growth. Asian and Pacific Forum, 12, 5–8.

Crone, T. M., & Mills, L. O. (1991). Forecasting trends in the housing stock using age-specific demographic projections. Journal of Housing Research,2(1), 1–20.

Crosbie, T. (2008). Household energy consumption and consumer electronics: The case of television. Energy Policy,36(6), 2191–2199.

Crowley, F.D. (2004). Pikes Peak Area Council of Governments: Small Area Estimates and Projections 2000 through 2030. Southern Colorado Economic Forum, University of Colorado at Colorado Springs. Retrieved from http://www.ppacg.org/Trans/2030/Volume%20III/Appendix%20G%20%20Small%20Area%20Forecasts.pdf.

Dalton, M., O’Neill, B. C., Prskawetz, A., Jiang, L., & Pitkin, J. (2008). Population aging and future carbon emissions in the United States. Energy Economics,30(2), 642–675.

Davis, L. W. (2008). Durable goods and residential demand for energy and water: Evidence from a field trial. The Rand Journal of Economics,39(2), 530–546.

Department for Communities and Local Government of United Kingdom (DCLGUK). (2010). Household Projections, 2008 to 2033, England. Retrieved from http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/statistics/pdf/1780763.pdf.

Egan-Robertson, D., Harrier, D. & Wells, P. (2008). A Report on Projected State and County Populations and Households for the Period 2000–2035 and Municipal Populations, 2000–2030. Retrieved from http://www.doa.state.wi.us/docview.asp?locid=9&docid=2108.

Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics (FIFARS). (2010). Older Americans 2010: Key Indicators of Well-Being. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.aoa.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2010_Documents/Docs/OA_2010.pdf.

Feng, Q., Wang, Z., Gu, D., & Zeng, Y. (2011). Household vehicle consumption forecasting in the United States, 2000 to 2015. International Journal of Market Research,53(5), 593–618.

Francesca, C., Ana, L. N., Jérôme, M., & Frits, T. (2011). Help wanted? Providing and paying for long-term care: Providing and paying for long-term care. OECD Health Policy Studies: OECD Publishing.

Gu, D., Feng, Q, Wang, Z., & Zeng, Y. (2015). Recommendation to consider the crucial impacts of trends in smaller household size on sustainable development goals. Crowdsourced Briefs for The Global Sustainable Development Report. Retrieved from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/7021Recommendation%20to%20consider%20the%20crucial%20impacts%20of%20trends%20in%20smaller%20household%20size%20on%20sustainable%20development.pdf.

Hu, P.S. & Reuscher, T.R. (2004). Summary of Travel Trend: 2001 National Household Travel Survey. Retrieved from http://nhts.ornl.gov/2001/pub/STT.pdf.

Ip, F. & McRae, D. (1999). Small Area Household Projections—A Parameterized Approach. Population Section, Ministry of Finance and Corporate Relations, Province of British Columbia, Canada. Retrieved from http://www.bcstats.gov.bc.ca/data/pop/pop/methhhld.pdf.

Jiang, L., & O’Neill, B. C. (2007). Impacts of demographic trends on US household size and structure. Population and Development Review,33(3), 567–591.

Jiang, L. O’Neill, B.C., & von Winterfeldt, D. (2009). Household Projections for Rural and Urban Areas of Major Regions of the World (Interim Report IR-09-026). International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, Laxenburg, Austria. Retrieved from http://www.cgd.ucar.edu/ccr/boneill/publications/Jiang&ONeill.2009.IIASAir.hhprojections.pdf.

Keilman, N. (2003). Biodiversity: The threat of small households. Nature,421(6922), 489–490.

Keilman, N., & Christiansen, S. (2010). Norwegian elderly less likely to live alone in the future. European Journal of Population,26(1), 47–72.

Klinenberg, E. (2012). Going solo: The extraordinary rise and surprising appeal of living alone. New York: Penguin Press.

Liu, J., Daily, G. C., Ehrlich, P. R., & Luck, G. W. (2003). Effects of household dynamics on resource consumption and biodiversity. Nature,421, 530–533.

Maldonado, L. C., & Nieuwenhuis, R. (2015). Family policies and single parent poverty in 18 OECD Countries, 1978–2008. Community, Work & Family,18(4), 395–415.

Masnick, G.S. & Di, Z.X. (2003). Projections of U.S. Households by race/Hispanic origin, age, family type, and tenure to 2020: A sensitivity analysis. Published in Issue Papers on Demographic Trends Important to Housing. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research.

Mason, A., & Racelis, R. (1992). A comparison of four methods for projecting households. International Journal of Forecasting,8, 509–527.

Mofitt, R. A. (2000). Demographic change and public assistance expenditures. In A. J. Auerbach & R. D. Lee (Eds.), Demographic change and public assistance expenditures (pp. 391–425). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Morris, R., Caro, F. G., & Hansan, J. E. (1998). Personal assistance: The future of home care. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Murphy, M. (1991). Modelling households: A synthesis. In M. J. Murphy & J. Hobcraft (Eds.), Population research in Britain, a supplement to population studies (Pp. 151–176). London, UK: Population Investigation Committee, London School of Economics.

Myers, D., & Ryu, S. (2008). Aging of the baby boomers and the generational housing bubble: Foresight and mitigation of an epic transition. Journal of the American Planning Association,74(1), 17–33.

Nelson, A. C. (2006). Leadership in a new era. Journal of the American Planning Association,72(4), 393–405.

Nelson, A. C. (2011). The new california dream: How demographic and economic trends may shape the housing market. Washington, D.C.: Urban Land Institute.

Nishioka, H., Koyama, Y., Suzuki, T., Yamauchi, M., & Suga, K. (2011). Household projections by prefecture in Japan: 2005–2030: Outline of results and methods. The Japanese Journal of Population,9(1), 78–133.

O’Neill, B. C., & Chen, B. S. (2002). Demographic determinants of household energy use in the United States. Population and Development Review,28, 53–88.

O’Neill, B. C. & Jiang, L. (2007). Projecting U.S. household changes with a new household model. IIASA Interim Report. IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria.

Painter, G., & Lee, K. (2009). Housing tenure transitions of older households: Life cycle, demographic, and familial factors. Regional Science and Urban Economics,39(6), 749–760.

Pittinger, D. B. (1976). Projecting state and local populations. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Ballinger.

Prskawetz, A., Jiang, L., & O’Neill, B. C. (2004). Demographic composition and projections of car use in Austria. In T. Fent & A. Prskawetz (Eds.), Vienna yearbook of population research 2004 (pp. 274–326). Vienna, Austria: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press.

Rao, J. N. K. (2003). Small area estimation. New York: Wiley.

Rayer, S., & Smith, S. K. (2010). Factors affecting the accuracy of subcounty population forecasts. Journal of Planning Education and Research,30(2), 147–161.

Rayer, S., & Wang, Y. (2017). Projections of Florida population by county, 2020–2045, with estimates for 2016. Florida Population Studies,50, 177.

Rives, N. W., Serow, W. J., Lee, A. S., Goldsmith, H. F., & Voss, P. R. (1995). Basic methods for preparing small-area population estimates. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin-Madison/Extension, Applied Population Laboratory.

Smith, S. K., Rayer, S., & Smith, E. A. (2008). Aging and disability: Implications for the housing industry and housing policy in the United States. Journal of the American Planning Association,74(3), 289–305.

Smith, S. K., Rayer, S., Smith, E. A., Wang, Z., & Zeng, Y. (2012). Population aging, disability and housing accessibility: Implications for sub-national areas in the United States. Housing Studies,27(2), 252–266.

Smith, S. K., Tayman, J., & Swanson, D. A. (2001). State and local population projections and analysis. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Spicer, K., Diamond, I., & Bhrolcham, M. N. (1992). Into the twenty-first century with British households. International Journal of Forecasting,8, 529–539.

Stupp, P.W. (1988). A general procedure for estimating intercensal age schedules. Population Index, 54, 209–234.

Swanson, D.A. & Pol, L.G. (2009). Applied demography: Its business and public sector Components. In Y. Zeng (Eds.), Demography, Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) (www.eolss.net), coordinated by the UNESCO-EOLSS Committee. Oxford, UK: EOLSS Publishers Co. Ltd.

United Nations. (1973). Methods of projecting households and families. New York: United Nation Publications.

United Nations. (1989). Projection methods for integrating population variables into development planning. New York: United Nation Publications.

United Nations. (2001). Approaches to Family Policies: A Profile of Eight Countries. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/family/Publications/familypolicies.PDF.

U.S. Census Bureau. (1996). Projections of the Number of Households and Families in the United States: 1995 to 2010 (Current Population Reports P25-1129). U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/1/pop/p25-1129.pdf.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2005). Indicators of Marriage and Fertility in the United States from the American Community Survey: 2000 to 2003. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/hhes/fertility/data/acs/indicators.html.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2006). Table MS-2: Estimated Median Age at First Marriage, by Sex: 1890 to the Present. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/ms2.pdf.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2008). National Population Projections (Based on Census 2000), Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/summarytables.html.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2013). Subnational Projections Toolkit User’s Guide.

Willekens, F. (2010). Family and household demography. In Y. Zeng (Ed.), Encyclopedia of life support systems vol 2 demography (pp. 86–112). Oxford: UNESCO in partnership with EOLSS Publishers.

Wilson, T. (2013). The sequential propensity household projection model. Demographic Research,28, 681–712.

Yamagata, Y., Murakami, D., & Seya, H. (2015). A comparison of grid-level residential electricity demand scenarios in Japan for 2050. Applied Energy,158, 255–262.

Yelowitz, A. S. (1998). Will extending Medicaid to two-parent families encourage marriage? Journal of Human Resources,33, 833–865.

Zeng, Y., Coale, A, Choe, M. K., Liang, Z. & Liu, L. (1994). Leaving parental home: Census based estimates for China, Japan, South Korea, the United States, France, and Sweden. Population Studies, 48(1), 65–80.

Zeng, Y., Land, K. C., Wang, Z., & Gu, D. (2006). US Family household dynamics and momentum—Extension of ProFamy method and application. Population Research and Policy Review,25(1), 1–41.

Zeng, Y., Land, K. C., Wang, Z., & Gu, D. (2013). Household and population projections at sub-national levels: An extended cohort-component approach. Demography,50(3), 827–852.

Zeng, Y., Land, K. C., Gu, D & Wang, Z. (2014). Household and living arrangement projections: The extended cohort-component method and applications to the U.S. and China. New York: Springer.

Zeng, Y., Morgan, P., Wang, Z., Gu, D. & Yang, C. (2012). A multistate life table analysis of union regimes in the United States—Trends and racial differentials, 1970–2002. Population Research and Policy Review, 31, 207–234.

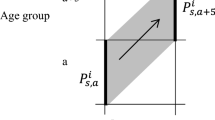

Zeng, Y., Vaupel, J. W., & Wang, Z. (1997). A multidimensional model for projecting family households—With an illustrative numerical application. Mathematical Population Studies,6(3), 187–216.

Zeng, Y., Vaupel, J. W., & Wang, Z. (1998). Household projection using conventional demographic data. Population and Development Review,24, 59–87.

Zeng, Y., Wang, Z., Jiang, L., & Gu, D. (2008). Future trend of family households and elderly living arrangement in China. GENUS: An International Journal of Demography, LXIV,1–2, 9–36.

Acknowledgements

Yi Zeng’s research on this paper was supported by National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (71490732). We appreciate very much for Frans Willekens’ thoughtful comments on our manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Procedures to Estimate Race-Specific Life Expectancies at Birth for California

As the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) only releases life expectancies at birth for California without four race categories, the race-sex-specific life expectancies at birth, e(r), are thus estimated based on the race-specific life expectancies at birth at national level by the following formula (for simplicity, the sex dimension is omitted hereafter):

where e is life expectancy at birth for all races combined in California, en(r) and en are race-specific life expectancy at birth and life expectancy at birth for all races combined at national level, released by NCHS. We then adjust e (r) to make sure that the weighted average of e (r) (using proportions of population size of each race group as weight) is equal to e:

where p (r) is the proportion of persons of race r among the total population in the state of California, \(\sum\limits_{r} {p(r) = 1.0}\)

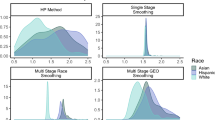

Procedures to Estimate Race-Specific Mean Age at First Marriage

The national data for median age at first marriage are available from the US Census Bureau (2006), but the state-level data of mean age at first marriage are not available. Using the pooled survey data, we first calculate a sex-specific ratio of mean age at first marriage to median age at first marriage for all races combined at the national level. By applying this ratio to the sex-specific median age at first marriage for all races combined of California published by the US census Bureau (2005), we obtain the all-races-combined sex-specific mean age at first marriage (\(\overline{M}\)) for California. We then estimate the sex-race-specific mean age at first marriage \(\left( {\overline{M} (r)} \right)\) for California using the following procedure:

where \(\overline{M}_{\text{n}}\) and \(\overline{M}_{\text{n}} (r)\) are sex-specific mean age at first marriage for all races combined and for race r at national level, both estimated through the pooled survey data. \(\overline{M} (r)\) is then adjusted to make sure that the weighted average (using proportions of each race group as weight) is equal to the all-races-combined sex-specific mean age at first marriage in the state of California.

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, Q., Wang, Z., Choi, S. et al. Forecast Households at the County Level: An Application of the ProFamy Extended Cohort-Component Method in Six Counties of Southern California, 2010 to 2040. Popul Res Policy Rev 39, 253–281 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-019-09531-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-019-09531-4