Abstract

Scholars have argued that racial policy beliefs contributed to a decline in public trust among white-Americans, but this effect waned over time as racial policies left the agenda. We theorize that beliefs about racial policies may have been integrated into whites’ racial attitudes, resulting in a durable association between racial prejudice and public trust. Our analysis of eight ANES surveys (1992–2020) shows that racial prejudice, measured in terms of anti-Black stereotypes, informs white Americans’ beliefs about the trustworthiness of the federal government. LDV models strengthen our contention by showing that the relationship persists after an LDV is included and it is not reciprocal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The long-standing malaise about government in America has led scholars to inquire into the origins and consequences of low public trust. The consensus in the public opinion literature is that short-term factors, such as the direction of the economy and the policies and personnel of an administration (e.g., Citrin, 1974; Weatherford, 1984), drive the ebbs and flows of public trust. In this view, people become dissatisfied with government performance and express this dissatisfaction in terms of trust in government. In turn, this public mistrust has significant consequences for the ability of government to deliver—especially on policies that involve concentrated costs/benefits, such as those that address income inequality (Hetherington & Rudolph, 2015).

The Great Society introduced new federal policies such as income support for the poor, housing subsidies, and affirmative action, promising to address inequality. However, these interventions allocated costs and benefits differentially across whites and minority groups—or were perceived to do so. As a result, many white Americans of the era believed that these new programs unfairly benefited African–Americans (Gilens, 1999). Scholars argued that these negative policy perceptions contributed to the decline in public trust among whites in the 1970s and 1980s, with significant consequences for the federal government’s ability to address economic inequality (Hetherington, 1998, 2005; Hetherington & Globetti, 2002).

By the 1990s, the federal government’s efforts to address racial inequality through race-based programs had all but ended and even reversed (Soss et al., 2003). Furthermore, by this time, white Americans had incorporated their views of racial policy into their assessments of government and thus the effect of race policy as a driver of public trust was thought to have diminished (Hetherington, 2005). Yet, low political trust persists among white Americans. This raises an important question: at a time when racial policy is no longer actively on the agenda, and the effect of attitudes about such policies on public trust may have declined, are racial factors not an influence on white Americans’ judgements of the federal government?

Studies in psychology suggest that human memory organizes thoughts in interrelated networks that are linked by affective ties (Lodge & Taber, 2013). Race-related beliefs are organized in well-developed and affectively-laden groups which are highly accessible and easy to recall unconsciously (Tesler & Sears, 2010; Winter, 2008). We argue that whites’ beliefs and attitudes about racial policies have become integrated into their broader racial attitudes toward Black people. As a result of this integration process, perceptions about the government’s trustworthiness have become associated in memory with negative attitudes about African–Americans. Thus attitudes about government have become “racialized,” that is people have developed a durable unconscious association between racial prejudice and public trust.

If this is the case, when racial attitudes become salient, or “primed,” through external stimuli, such as the media or political elites, mistrust in government increases among racially prejudiced whites for whom racial prejudice is top of mind. Even if the policies themselves are no longer consequential in shaping whites’ trust in government (Hetherington, 2005), racial prejudice can directly influence trust in government. The racialization of government may explain why racially-prejudiced whites perceive the federal government as not “their own” (Parker & Barreto, 2013).

This perspective is important for several reasons. First, it provides one explanation for why public trust among whites has not rebounded even as racial policy moved off the political agenda in the 21st century. Second, it suggests that the link between racial priors and public trust may be durable and chronically salient. Third, this indicates that among racially prejudiced whites, priming of racial attitudes may also prime mistrust in government even if racial policies are not mentioned. Furthermore, the racialization of government trust provides another path for the theorized “spillover” of racialization which is currently attributed to the Obama Presidency (Tesler, 2016). Given that trust in government is known to influence support for various policies (Hetherington, 2005; Hetherington & Rudolph, 2015), the racialization of government trust may have contributed to the racialization of various policy domains previously considered to be non-racial. Finally, the racialization of public trust may have implications for the ability of government to address the issues of social justice raised by the Black Lives Matter mobilization. This mobilization may make anti-Black attitudes more salient among whites, further dampening public trust.

We test the relationship between whites’ racial attitudes and trust in government using eight ANES surveys (1992–2020). First, our results show that racial prejudice, measured in terms of anti-Black stereotypes, is a negative and significant predictor of public trust across the series, controlling for economic evaluations, evaluations of the President, partisanship, ideology authoritarian personality, trust in people and demographic factors. Parallel analyses show that racial policy has less consistent effects on public trust. Second, parallel analyses with a dependent variable related to public trust—political efficacy—yield very similar results. Third, an LDV model using the 1992–1996 ANES data shows that racial prejudice remains significant even after the inclusion of a lagged dependent variable. The reverse model shows null effect of public trust on racial prejudice when a lagged DV is included. Finally, we show that the negative relationship between racial prejudice and public trust remains robust even if we include restrictive immigration policy preferences in the model.

Public Trust

The concept of public trust seems straightforward, but it is actually quite complex both to conceptualize and to measure. According to Easton (1965), trust can be thought of in terms of support for a given government’s policies, or as faith in the political system itself. There is some dissension in the literature as to whether political trust measures tap satisfaction with policy performance or system level support (Craig et al., 1990; Hetherington, 1998; Norris, 2011). Scholars of political trust generally believe that as measured in the standardized ANES battery, the construct most likely taps attitudes about satisfaction with a given administration’s performance and policy direction (Hetherington, 2005). In this sense, political trust refers to a citizen’s evaluation of whether or not the government acts on behalf of the public good (Craig, 1979). Public trust is typically measured using four items: “how often can you trust the federal government in Washington to do what is right,” “Would you say the government is pretty much run by a few big interests looking out for themselves or that it is run for the benefit of all the people,” “do you think that people in government waste a lot of the money we pay in taxes,” and “how many of the people running the government are corrupt.” The focus of these items is generally corruption and waste in Washington, likely tapping assessments about government outputs—that is how policies allocate collective resources.

Not surprisingly, it is beliefs about the political personnel, the state of the economy, and the government’s policy choices that predict public trust. People who dislike the president’s character or leadership style (Citrin & Green, 1986), or who find his behavior scandalous tend to express lower levels of political trust (Chanley et al., 2000). Citizens who are dissatisfied with the direction of the economy (Hetherington & Rudolph, 2008; Weatherford, 1984), or who are concerned about crime (Chanley et al., 2000) tend to also be mistrustful. Similarly, those who are resentful with the way the government distributes or redistributes resources tend to be mistrustful of government (Hetherington, 2005).

Racial Policy and Public Trust

In the United States, a key cleavage that continues to be central to citizens’ political judgements is race. Black inclusion to political rights arrived not as the result of a social consensus but rather through changes instituted and enforced by government: first the Supreme Court and then Congress dismantled Jim Crow and mandated Blacks’ political rights. These institutional changes contributed to important attitudinal change: support for white supremacy and beliefs in white biological superiority declined markedly following the Civil Rights revolution (Schuman et al., 1997). However, this change did not mean that racial prejudice subsided or that it no longer had substantial influence on whites’ political judgements (Sides et al., 2019; Tesler, 2016).

The institutional and policy changes that accompanied desegregation and the “nationalization of implicitly and explicitly racial policies,” produced noticeable declines in political trust among whites (Hetherington, 2005, 21). The transformation of small social welfare programs to massive entitlements which coincided with the Civil Rights transformation and guaranteed blacks equal access to state supported programs, fueled white mistrust. As Hetherington (2005) has shown, especially in the 1970s, resistance to racial policies such as busing and government aid to Blacks contributed substantively to the decline in public trust among whites. In this view, whites may have thought of such policies as programs that imposed direct material costs on their group while benefiting Blacks exclusively and this perceived unfair allocation in costs and benefits may have fueled their mistrust in government. However, Hetherington’s analysis shows that racial policies ceased having an effect on public trust by the 1990s. According to Hetherington, this was the case because these programs were no longer new and thus the public had already integrated their perceptions of race policy into their attitudes about government (Hetherington, 2005). If race policies no longer influence white opinion on government performance, does that mean that racial considerations have no bearing on white Americans’ trust in government?

Racial Attitudes and Public Trust

Political psychologists have shown that concepts related to race, such as beliefs about African–Americans (racial prejudice) and beliefs about racial policy, are closely networked and linked in people’s memory and these associations are stored together along with an overall evaluative tally. More so than the specific underlying information, for example about the policy content, it is the general positive or negative evaluation related to this network of interlinked beliefs about racial groups that is easily accessible and people can quickly retrieve when prompted to consider race-related topics. Therefore, if in the white mind government performance is linked to an associative network of beliefs related to Black people, then individuals are likely to unconsciously draw from this set of beliefs when asked to respond to questions about public trust (Tesler & Sears, 2010).

Over time, racial policy-specific beliefs may become less central and less coherent when it comes to white-Americans assessment of government performance. These policies may move on and off the agenda and as they do so, they become less top-of-mind when individuals are asked to evaluate the federal government (Hetherington, 2005). However, even if racial policy beliefs remain salient, such beliefs will still likely be connected to the individual’s broader beliefs about African–Americans. Therefore, thinking about the performance of the federal government is likely to also activate thoughts about Black people and thus negative assessments of African–Americans may influence judgements about the trustworthiness of the government.

Among white Americans, racial beliefs are well-developed, strongly associated to each other and easily accessible (Winter, 2008). The accessibility of these ideas suggests that racial considerations are easily primed, meaning that information encountered in the environment can prompt people to automatically recall these ideas below consciousness. In turn, these racial considerations can influence subsequent thoughts, disproportionately weighing on candidate assessments (Buyuker et al., 2021; Mendelberg, 2001), policy preferences (Filindra & Kaplan, 2016; Tesler, 2016), or –in this case—attitudes about the government itself. Thus, even when racial policy issues are no longer on the agenda, feelings about such policies may continue to influence judgements about the government’s trustworthiness.

The democratization of the polity ushered in by the Voting Rights and Civil Rights Acts and the desegregation decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court, contributed to the development in the white mind of a link between racial attitudes and public trust in government. The race riots of the late 1960s likely strengthened this relationship. As early as 1970, Aberbach and Walker (1970) reported that in promoting racial integration in schools and neighborhoods, “government officials are faced with an increasingly angry, bitter and frightened group of white people who feel persecuted and unrepresented. These feelings are undermining their basic trust in government” (p. 64). Even after the battles over desegregation were over, white people’s feelings about the changes introduced by the Civil Rights era were likely incorporated into their attitudes about African–Americans. The same may be the case for affirmative action and welfare which exited the agenda by the late 1990s (Hetherington, 2005). This process was further aided by white reactionary movements, from the New Right, to the Tea Party, to “MAGA,” which actively linked racial grievances to government performance and beliefs about government trustworthiness (Parker & Barreto, 2013; Sides et al., 2019).

A link between white racial prejudice and mistrust in government has several implications. First, unlike public policies that can be abandoned and forgotten, racial prejudice emerges early and persists over the lifetime of individuals and is also transmitted across generations (Kinder & Sanders, 1996). This means that the effect of racial attitudes may not be limited to a specific time period when concerns about racial policies are new or salient. If attitudes about government are “racialized,” that is, connected in memory to beliefs about racial groups, then the abandonment of racial policy may not be sufficient to produce substantive increases in public trust among racially prejudiced whites. Other factors, such as the presence of prominent African–Americans in office or in government positions, or images of African-American social movements making claims on government may be sufficient to activate the negative associations between Black people and government performance. Such links may accentuate the belief among racially prejudiced whites that government is “not ours” that both the Tea Party and the MAGA movement expressed (Parker & Barreto, 2013; Sides et al., 2019).

Second, given that considerations about Black people are easily primed by political elites and the media (Mendelberg, 2001), and as a result of President Barack Obama and now Vice President Kamala Harris in the most prominent political roles in the federal system, racial prejudice may be chronically primed (Tesler & Sears, 2010). This suggests that elites with incentives to direct white racial prejudice toward government institutions can do so easily and effectively, and often in ways that don’t require conscious processing. Historical accounts of the New Right movement show that elites have employed racial priming to undermine trust in national government institutions by employing implicit racial frames (Edsall & Edsall, 1992).

Third, if beliefs about government are racialized, perhaps even chronically, then the effect of racial attitudes may spillover to many policy domains, racial and nonracial, where political trust is a factor. Hetherington’s (2005) research has already demonstrated that political trust moderates the effect of racial attitudes on support for various racial policies. If racial attitudes directly predict one’s level of political trust, then these results certainly suggest that racial priors have both direct and indirect effects—through political trust—on policies that are not thought to be subject to racialization. In Tesler’s (2016) terminology, attitudes about government may be another pathway through which “spillover of racialization” can occur, and one that well predates the Obama era.

Hypotheses

-

1.

We expect that racial prejudice (anti-Black stereotypes) is a negative and significant predictor of trust in government.

-

2.

We expect that attitudes towards racial policies should also be negatively correlated with public trust, but the relationship should be weaker and inconsistent over time.

ANES Analyses (1992–2020)

The dependent variable consists of the four items discussed earlier which are used in most of the research on public trust (e.g., Hetherington, 2005). When it comes to our predictors, racial prejudice is measured using a composite variable based on anti-Black stereotypes. There are many different ways to measure racial prejudice. One popular measure is that of modern racism or racial resentment which is considered the form of racial prejudice most prevalent today (Kinder & Sanders, 1996). However, for our purposes, modern racism is a suboptimal measure because critics have shown that it may conflate racial prejudice with ideology and policy preferences (Feldman & Huddy, 2005; Neblo, 2009). Ours is a measure of traditional rather than modern racial prejudice and thus does not suffer the limitations of the modern racism measure.

The stereotypes measure also has advantages relative to the Black thermometer measure. Thermometers have been included in the ANES since the 1960s, so in principle, using the thermometer would enable us to extend the analysis to the Civil Rights era. However, there is good reason to expect a low correlation between the Black thermometer and attitudes about government. The Black stereotype (and also racial resentment) are measures based on cognitions, that is, discreet types of thoughts about Black people. Public trust is a cognitive evaluation measure. However, the Black thermometer measures affect, that is positive or negative emotional responses to African–Americans. Psychologists have demonstrated that these are distinct processes. Cognitive beliefs or attitudes are linked to conceptual judgements, while affective responses are better correlated with other affect-based responses (Fiske & Taylor, 2013, 212–213).Footnote 1

We also refrain from using the difference in Black and white stereotypes as a measure. This is because studies assert that ingroup and outgroup attitudes fall on distinct dimensions and thus are not commensurable (Brewer, 1999). When white Americans think about the ingroup, these considerations are qualitatively different from those related to a racial outgroup. In essence, we don’t use the same standards to think about the ingroup as we use to assess outgroups (Jardina, 2019).Footnote 2

Across all ANES surveys includes one item that asks respondents to place Blacks on a seven-point continuum between lazy and hardworking. A second item, intelligent/unintelligent, is included in all except 2016 and 2020. For those years, ANES included a second item that measures stereotyping Blacks as violent or peaceful (7-pt). Figure 1a shows the distributions of the public trust for each year. The graphs show a fairly normal distribution with a large proportion of people in the middle. Figure 1b shows the distribution of our key independent variable—anti-Black stereotypes—for each ANES year. For most years, the data show a one-tailed distribution with relatively few people expressing strong anti-Black attitudes. This is consistent with what analyses of blatant prejudice report (Krysan, 2012).

For reasons of consistency, we use two policy items that have appeared in all surveys: support for affirmative action (preferential hiring) and support for government help (aid to Blacks).Footnote 3 Models that include policy are in the supplemental Appendix. Consistent with earlier research trust in government, the cross-sectional models control for support for the president (thermometer), trust in people, authoritarian personality, prospective economic evaluation, partisanship, and ideology (Citrin, 1974; Hetherington, 2005; Weatherford, 1984). The models also account for key demographics: gender, age, education, income, residence in the South, and religion (Protestant). In all models, we only include respondents who self-identified as non-Hispanic whites. All variables in the models are rescaled on 0–1 scales consistent with the nature of the original variable. This allows us to conceptualize the coefficients as maximum effects and consequently compare the size of coefficients across models. Descriptive statistics and exact wording of the items can be found in Appendix A7.

We specified OLS regression models for each of the cross-sectional ANES surveys from 1992 to 2020.Footnote 4 Since racial policy preferences and racial prejudice are likely endogenous, we run separate sets of models with prejudice and racial policy to assess the degree to which these two factors consistently predict government mistrust.Footnote 5

First, Table 1, shows the results including racial prejudice but not racial policy preferences. Given that public trust is thought to primarily tap beliefs about political performance, it is reassuring and consistent with expectations that the presidential thermometer is positively and significantly correlated with government trust across all surveys. As expected, all else being equal, positive evaluations of the economy also boost public trust: the measure is positive and significant in all surveys except 2000. Although trust in people is thought to have a relatively weak correlation with trust in government, our results indicate that the relationship is positive and significant in seven of the eight models. Partisanship and ideology are generally not significant in the models as much of the effect here is likely absorbed by the evaluation of the president. Authoritarianism is only significant in 2020. These results are reassuring since they are generally consistent with established literature.

Moving to the variable of central interest to us, as Table 1 shows, the coefficient associated with the Black stereotype measure is negatively signed and statistically significant at conventional levels (p < 0.05) in all years. The negative sign of the coefficient indicates that the more racially prejudiced a respondent is, the more mistrustful of government they are likely to be. This is consistent with our expectations.

In terms of substantive effects, the presidential thermometer is in a top tier of predictors and across the series has the strongest substantive effect. Since all predictors are recoded on 0 to 1 scales, the coefficients can be understood as the “maximum” effect of the variable, that is, the change in probability if we switch the predictor from zero to one, holding all others constant. The maximum effect of the presidential evaluation ranges from + 0.05 in 2020 to + 0.25 in 2004. Not surprisingly, given the rhetoric of the Trump presidency, positive evaluations of Trump did not contribute much to trust in government.

Racial prejudice (stereotypes) can be placed in a second tier of predictors along with economic evaluation and trust in people. Its maximum effect ranged from a low of − 0.06 in 2016 to a high of − 0.23 in 1996. It is important to note that the effect of racial prejudice on trust in government does not seem to have increased in the Obama era, so we do not observe an “Obama effect” when it comes to the association between prejudice and public trust. In part, this could be because of the correlation between the Presidential thermometer and racial prejudice during this period.Footnote 6 These effects are in the same range as for trust in people and economic evaluation. Specifically, the substantive effect of trust in people ranges from a low of + 0.03 in 2016 to a high of + 0.11 in 2020. Similarly, the effect of economic evaluation ranges from a low of + 0.05 in 2020 to a high of + 0.12 in 2008 and 2016.

What about the effect of racial policy which theory suggests drives public trust (Hetherington, 2005)? Appendix Table A4 shows the same models as Table 1 except that we have replaced the stereotypes measure with two measures of racial policy: affirmative action (preferential hiring), and government help (aid to Blacks). The effect of the two policy items is inconsistent across surveys. The affirmative action item is statistically significant in 1992, 1996, 2012, 2016, and 2020 and its substantive effect is relatively small ranging from -0.01 in 2012 to − 0.13 in 1996. The government help item is statistically significant in 2000, 2012 and 2016 and the substantive effect ranges from − 0.04 in 2016 to − 0.12 in 2000. The measure was not included in 2020 (only one policy item was included in that year). These results suggest that even though racial policy continues to play some role in shaping white Americans’ trust in government, the effect is relatively small and inconsistent across surveys.Footnote 7

The ANES contains a second measure that is conceptually and operationally correlated with public trust (Craig, 1979; Craig et al., 1990). This is known as political responsiveness or external political efficacy. Political efficacy measures the degree to which people’ think that government is responsive to their demands. The relevant items can be found in Appendix A4. Since the two measures are closely related, we use political responsiveness to demonstrate the robustness of our results. As Appendix Table A5 shows, the anti-Black stereotype measure is negative and statistically significant in all models with the exception of 1992. The substantive effect of the stereotype measure ranges from − 0.10 in 2012 to − 0.22 in 2004. However, as Appendix Table A6 shows, there is less consistency in the effect of the racial policy measures on political responsiveness. Preferential hiring (affirmative action) is significant only in 2020 and government help is significant only in 2008 and 2012.

Lagged Dependent Variable Analysis (1992–1996 ANES Panel)

As a further robustness check, we used the 1992–1996 ANES panel survey to specify lagged dependent variable analyses (LDV). LDV analyses can be helpful in two ways. First, an LDV model of public trust can reassure us that our results are not an artifact of omitted variable bias. Second, we can use the anti-Black stereotype as the DV to test for reverse causation. Theory suggests that racial prejudice is formed early in childhood while attitudes about government and the political system emerge much later (Kinder & Sanders, 1996; Sears & Henry, 2003). However, the panel data enable us to test the possibility of a reciprocal relationship rather than take the direction of effect for granted.

The 1992 (post) election wave and the 1996 (post) election wave included the stereotype questions. Consequently, we ran a lagged DV model using this dataset. In other words, we ran a model which was identical to the model used to analyze the 1996 cross-sectional data, except we added a lagged dependent variable (from the 1992 wave) to the right-hand side of the model. As specified in the introduction of the codebook of the panel dataset, there are 545 cases that participated in relevant four waves (the pre and post waves of 1992 survey and the pre and post waves of the 1996 survey). Non-white respondents are dropped since we restrict the analysis to whites only. Of the remaining 469 cases, 33 are lost to item non-response. Please note that the ANES did not provide weights for the 545 panel cases.

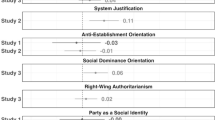

The LDV results are in Table 2. The first model uses political trust as the dependent variable. Controlling for the 1992 measure of trust in government, we show that the Black stereotypes measure is negative and statistically significant (p < 0.05, one tailed). Given the directional orientation of our hypothesis, a one-tailed test is sufficient to reassure us that prejudice depresses political trust. However, the same is not true for the second model which uses anti-Black stereotypes as the dependent variable. Here, when the 1992 measure of negative Black stereotypes is taken into account, government trust is not a statistically significant predictor of the 1996 negative Black stereotype measure and its substantive effect is close to zero. This reassures us that the relationship is not endogenous and it likely runs from racial prejudice to trust in government, not the other way around.

What About Anti-immigrant Policy Preferences?

Finally, another important consideration is the possibility that other outgroup attitudes or outgroup-related policy preferences may also have an effect on public trust. Although American political and social hierarchies are primarily built on the white/Black divide, there is evidence of a second important cleavage in shaping whites’ political judgements. This is the native/foreign cleavage (Zou & Cheryan, 2017). A large number of studies have shown that anti-immigrant attitudes influence policy preferences (e.g., Filindra & Pearson-Merkowitz, 2013; Pearson-Merkowitz et al., 2016). Studies from Europe show that anti-immigrant attitudes do negatively influence government trust (McLaren, 2012). It is thus possible that the effect of anti-Black stereotypes reflects anti-immigrant attitudes and once we control for that factor, the effect of anti-Black stereotypes will diminish or disappear. The ANES surveys include one item related to immigration that is consistent across all cross-sectional studies. This item asks: “Do you think the number of immigrants from foreign countries who are permitted to come to the United States to live should be increased a lot, increased a little, left the same as it is now, decreased a little, or decreased a lot?” This item measures immigration policy preferences not attitudes about immigrant groups. We recoded this item to range from 0 to 1 in the direction of stronger anti-immigrant policy preferences. We then re-specified the models from Table 1 to include this item. Results of these analyses are included in Appendix Table A9. The results show that even when anti-immigrant policy preference is accounted for, the negative Black stereotype measure continues to be statistically significant in all eight models and the substantive effects do not change markedly. Support for immigration restrictionism is also negative and significant in six of the eight models and its effects tend to be similar or qualitatively smaller than those of the anti-Black stereotype measure. However, given that this is not a measure of group attitudes but rather immigration policy preferences, we resist any conclusion that anti-immigrant attitudes are directly implicated in the decline of public trust. For our purposes, these results strengthen our assertion that anti-Black prejudice depresses public trust even controlling for immigration restrictionism. Future research should focus on the role of attitudes towards immigrants and other racial groups—such as Latinos— and ethnocentrism more broadly in shaping white attitudes toward government.

Taken together, our ANES findings provide support for the theory that racial attitudes predict lower trust in government and they do so consistently over more than two decades. Therefore, the ANES data suggest that racial attitudes have become intertwined with political trust in the white mind. Furthermore, we have no evidence that the relationship is reciprocal with public trust influencing anti-Black prejudice. Furthermore, the effect of racial policy is weaker and less consistent over time.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that white Americans’ beliefs about the trustworthiness of the federal government have become linked with their racial attitudes. The study shows that even when racial policy preferences are weakly linked to trust in government racial prejudice does not. Analyses of eight surveys of the ANES from 1992 to 2020 show a negative correlation between racial prejudice (measured in terms of anti-Black stereotypes) and trust in government which is significant statistically and substantively, as well as persistent. Replication of these models using political responsiveness as the dependent variable—a measure closely linked to public trust—further strengthen our contention. Furthermore, LDV analyses of the 1992–1996 ANES panel provides additional evidence for the one-directional link between prejudice and public trust among white Americans. Overall, our ANES analyses indicate a significant negative association between Black stereotypes and public trust that has persisted over three decades and which exists independent of racial policy attitudes.

More research is necessary to understand the mechanisms that underline these responses. For example, our data cannot address the question of whether the decline in public trust is related to whites’ perceptions of loss of political power to African–Americans within the electorate through the emergence of a “majority-minority” voter base, or whether it is caused by the growing numbers of African-American public officials who are expected to represent Black interests at the detriment of white interests. We are not able to ascertain whether and to what degree it is the changing face of the electorate, the changing face of government or a combination of both that may be driving low public trust among whites.

The racialization of public trust can have major implications for American political life. Over time, the feedback process of grievance and mistrust can undermine the effectiveness of national institutions in enacting and enforcing policies meant to protect minority and immigrant rights, and address social and economic inequality. The racialization of government trust, as we are witnessing in real time today in the context of the COVID-19 crisis, can introduce serious obstacles in the ability of government to enforce rules and regulations meant to sustain the general welfare, including the democratic process itself.

Furthermore, these analyses can be used as the impetus to ask similar questions about trust in other divided societies and even minority groups that inhabit a middling position within racial hierarchies—such as Asians and Latinos. Racial and ethnic cleavages exist across the world, in democratic and authoritarian countries alike. It is worth investigation whether group conflicts in other institutional contexts are linked to attitudes toward government and whether this relationship endures even as policy conflict comes and goes. In the United States, studies suggest that Latinos are embracing white identity (Filindra & Kolbe, 2020) with important implications for partisanship, ideology, and policy preferences. Such processes could also influence public trust.

Finally, the stability of the relationship between racial prejudice and public trust challenges the conclusion that public trust evaluations are simply about government performance and outputs. If the racialization of public trust is related to the political empowerment of African–Americans and the increased visibility and power of Black elected officials, then it is possible that prejudiced whites are not simply disaffected by government performance but rather feel that the institutions themselves do not represent their group interests. Our analyses cannot disentangle the question of meaning, but they do suggest that performance may not be the only thing that public mistrust measures. Especially in the post January 6th era, and in the context of studies linking prejudice to white support for anti-democratic norms (Bartels, 2020; Buyuker & Filindra, 2020; Miller & Davis, 2021), this possibility deserves to be taken seriously and investigated further.

Change history

20 September 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09822-1

18 February 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09778-2

Notes

Models with the Black thermometer as the key independent variable are included in Appendix Table A7. As expected, the thermometer does not perform as well as the stereotypes. Although all except one coefficients are in the expected direction, only three (1992, 2000, 2008) are statistically significant.

Factor analysis of the Black and white stereotype items in the ANES confirms that they do not fall on a single dimension. See Appendix Table A2.

The 2020 ANES included only one racial policy item: affirmative action. Following Hetherington (2005), we use individual policy controls, one for each policy, but our results as far as the significance of racial prejudice remain consistent if an additive policy index is used instead.

The 1988 ANES did not include measures of racial stereotypes, so we did not include it in the analysis. We use the time series data files in the analysis not the cumulative ANES file because the 2020 data are not in the cumulative file.

Results with both factors in the same model can be found in Appendix Table A3. These results are similar to what we present here.

Removal of the Presidential thermometer from the models leads to an increase in the size of the coefficients for the Black stereotype measure.

This remains the case in models in which the Black stereotypes are included in the same models as racial policy. See Appendix Table A3.

References

Bartels, L. M. (2020). Ethnic antagonism erodes Republicans’ commitment to democracy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117, 22752–22759. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007747117

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00126

Buyuker, B., Filindra, A. (2020). Democracy and “the other”: Anti-immigrant attitudes and white support for anti-democratic norms. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3585387. Accessed 15 Oct 2020.

Buyuker, B., D’Urso, A. J., Filindra, A., & Kaplan, N. J. (2021). Race politics research and the American presidency: Thinking about white attitudes, identities and vote choice in the Trump era and beyond. The Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, 5(3), 600–641.

Chanley, V. A., Rudolph, T. J., & Rahn, W. M. (2000). The origins and consequences of public trust in government: A time series analysis. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 64(3), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.2307/3078718

Citrin, J. (1974). Comment: The political relevance of trust in government. American Political Science Review, 68, 976–977.

Citrin, J., & Green, D. P. (1986). Presidential leadership and the resurgence of trust in government. British Journal of Political Science, 16(4), 431–453. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400004518

Craig, S. C. (1979). Efficacy, trust, and political behavior: An attempt to resolve a lingering conceptual dilemma. American Politics Research, 7(2), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673x7900700207

Craig, S. C., Niemi, R. G., & Silver, G. E. (1990). Political efficacy and trust: A report on the NES pilot study items. Political Behavior, 12(3), 289–314.

Easton, D. (1965). A system analysis of political life. Wiley.

Edsall, T. B., & Edsall, M. D. (1992). Chain reaction: The impact of race, rights, and taxes on American politics. W.W. Norton & Co.

Feldman, S., & Huddy, L. (2005). Racial resentment and white opposition to race-conscious programs: Principles or prejudice? American Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 168–183.

Filindra, A., & Kaplan, N. J. (2016). Racial resentment and whites’ gun policy preferences in contemporary America. Political Behavior, 38(2), 255–275.

Filindra, A., & Melanie, K. (2020). Are latinos becoming white? The role of white self-categorization and white identity in shaping contemporary hispanic political and policy preferences. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3602372

Filindra, A., & Pearson-Merkowitz, S. (2013). Together in good times and bad? How economic triggers condition the effects of intergroup threat. Social Science Quarterly, 94(5), 1328–1345.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (2013). Social cognition: From brains to culture (2nd ed.). Sage.

Gilens, M. (1999). Why Americans hate welfare: Race, media and the politics of antipoverty policy. University of Chicago Press.

Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The political relevance of political trust. The American Political Science Review, 92(4), 791–808. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586304

Hetherington, M. J. (2005). Why trust matters. Princeton University Press.

Hetherington, M. J., & Globetti, S. (2002). Political trust and racial policy preferences. American Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 253–275. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088375

Hetherington, M. J., & Rudolph, T. J. (2008). Priming, performance, and the dynamics of political trust. The Journal of Politics, 70(2), 498–512. https://doi.org/10.2307/30218903

Hetherington, M. J., & Rudolph, T. J. (2015). Why Washington won’t work. University of Chicago Press.

Jardina, A. (2019). White identity politics. Cambridge University Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. M. (1996). Divided by color. University of Chicago Press.

Krysan, M. (2012). From color caste to color blind, part II: Racial attitudes during the civil rights and black power earas, 1946–1975. In H. L. Gates, C. Steele, L. D. Bobo, M. C. Dawson, G. Jaynes, L. Crooms-Robinson, & L. Darling-Hammond (Eds.), The oxford handbook of African-American citizenship, 1865-present (pp. 195–234). Oxford University Press.

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2013). The rationalizing voter. Cambridge University Press.

McLaren, L. M. (2012). The cultural divide in Europe: Migration, multiculturalism, and political trust. World Politics, 64(2), 199–241.

Mendelberg, T. (2001). The race card: Campaign strategy, implicit messages, and the norm of equality. Princeton Unniversity Press.

Miller, S. V., & Davis, N. T. (2021). The effect of white social prejudice on support for American democracy. The Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, 6(2), 334–351.

Neblo, M. A. (2009). Three-fifths a racist: A typology for analyzing public opinion about race. Political Behavior, 31(1), 31–51.

Norris, P. (2011). Democratic deficit: Critical citizens revisited. Cambridge University Press.

Parker, C. S., & Matt, A. B. (2013). Change they can’t believe in: The tea party and reactionary politics in America. Princeton University Press.

Pearson-Merkowitz, S., Filindra, A., & Dyck, J. J. (2016). When Partisans and minorities interact: interpersonal contact, partisanship, and public opinion preferences on immigration policy. Social Science Quarterly, 97(2), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12175

Schuman, H., Steeh, C., Bobo, L., & Krysan, M. (1997). Racial attitudes in America: Trends and interpretations. Harvard University Press.

Sears, D. O., & Henry, P. J. (2003). The origins of symbolic racism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 259–275.

Sides, J., Tesler, M., & Vavreck, L. (2019). Identity crisis: The 2016 presidential campaign and the battle for the meaning of America. Princeton University Press.

Soss, J., Sanford, S., & Richard, C. F. (2003). Race and the politics of welfare reform. UK: University of Michigan Press.

Tesler, M. (2016). Post-racial or most racial? Race and politics in the Obama era. University of Chicago Press.

Tesler, M., & Sears, D. O. (2010). Obama’s race: The 2008 election and the dream of a post-racial America. Chicago University Press.

Weatherford, M. S. (1984). Economic ‘stagflation’ and public support for the political system. British Journal of Political Science, 14(2), 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400003525

Winter, N. (2008). Dangerous frames how ideas about race and gender shape public opinion. University of Chicago Press.

Zou, L. X., & Cheryan, S. (2017). Two axes of subordination: A new model of racial position. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(5), 696–717.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Institute for Policy and Civic Engagement, and the Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy both at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We would like to thank the reviewers and the editor for their very constructive comments. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the MPSA and APSA conferences, and at the University of Illinois at Chicago Political Science Talk Series. Replication files for our analyses can be found in the Harvard dataverse repository (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId = doi:10.7910/DVN/FFT2PA).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Filindra, A., Kaplan, N.J. & Buyuker, B.E. Beyond Performance: Racial Prejudice and Whites’ Mistrust of Government. Polit Behav 44, 961–979 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09774-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09774-6