Abstract

Over the past two decades, political scientists have demonstrated that racial animus among white Americans is increasingly associated with evaluations of presidential candidates. Like most work on white racial attitudes, these efforts have focused almost exclusively on the out-group attitudes whites possess toward racial and ethnic minorities. Work in social psychology, however, suggests that intergroup attitudes are usually comprised of both an out-group and an in-group component. Nevertheless, political scientists have tended to overlook or dismiss the possibility that whites’ in-group attitudes are associated with political evaluations. Changing demographic patterns, immigration, the historic election of Obama, and new candidate efforts to appeal to whites as a collective group suggest a need to reconsider the full nature and consequences of the racial attitudes that may influence whites’ electoral preferences. This study, therefore, examines the extent to which both white out-group racial resentment and white in-group racial identity matter in contemporary electoral politics. Comparing the factors associated with vote choice in 2012 and 2016, and candidate evaluations in 2018, this study finds that both attitudes were powerfully associated with candidate evaluations in 2012 and early 2016, although white out-group attitudes overshadowed the electoral impact of in-group racial attitudes by the 2016 general election. The results suggest that there are now two independent racial attitudes tied to whites’ political preferences in the contemporary U.S., and understanding the dynamics of white racial animus and white racial identity across electoral contexts continues to be an important avenue for future work.

Source 2012 ANES

Source 2012 ANES (face-to-face)

Source 2016 ANES Pilot Study

Source 2016 ANES (face-to-face)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Criticisms of racial resentment are largely rooted in whether racial resentment is truly capturing racial animus, or if instead it is conflating racism with ideological conservatism (Sniderman and Carmines 1997).

Work in sociology has examined the concepts of whiteness and white identity through a very different lens. It has either treated white identity as an implicit attitude (Knowles and Peng 2005), considered whiteness as part of a system of racial inequality (e.g., Guess 2006), or has explored white identity as a progressive reckoning with racial inequality as part of a move toward social justice (Helms 1995). None of this work recognizes white in-group attitudes as I do here, and in a way that is in keeping with a social identity framework—as an explicit psychological attachment to a group that influences explicit attitudes and behavior.

When Wong and Cho (2005) undertook their study of white identity, the closeness items were the best proximate measure of identity available on a nationally representative public opinion survey. Scholars have previously argued, however, that the closeness measure captures group affect, rather than identity (Conover 1984; Herring et al. 1999).

Much of the work on the reaction of dominant groups to status threat has focused on the relationship between in-group identity and subsequent out-group derogation (Branscombe et al. 1999; Glaser 1994; Oliver and Mendelberg 2000). A multitude of studies across the social sciences have demonstrated that identity threat can promote out-group derogation, although the relationship is not inevitable (e.g., Branscombe et al. 1999; Brewer 1999; Gibson 2006).

Near the end of August 2015, immigration reform was the only issue on Trump’s campaign website: https://web.archive.org/web/20150824010152/https://www.donaldjtrump.com/positions.

Winter (2006) argues that political elites intentionally framed such policies as benefits for “hard work” to contrast them with prevailing negative racialized stereotypes about welfare, which has been associated with unearned handouts.

Replication files for all the analyses presented here are available on my personal website at www.ashleyjardina.com.

To avoid possible discrepancies across survey modes, I use only the face-to-face ANES samples.

YouGov maintains a panel comprised of a diverse population of respondents who volunteer to complete online surveys. Respondents are selected into the panel by sample matching, which effectively creates a respondent pool resembling the U.S. population with respect to gender, age, race, and education. The analysis here employs probability weights (Rivers 2006).

The measure of white consciousness developed by Jardina and employed by scholars like Sides et al. (2018) has the benefit of being comprised of several survey questions. However, many of the items used to construct the consciousness measure arguably incorporate in-group and out-group attitudes. For instance, one item asks respondents whether they think whites are being denied jobs because employers are hiring minorities instead. Thus, using them would not provide as clean of a test of the relationship between whites’ in-group and out-group racial attitudes as proposed here.

There are other measures of group solidarity, including linked fate. Dawson (2009) finds that white linked fate is unrelated to identity as conceived here. In fact, it is associated with more liberal positions on racialized policies. Furthermore, other work argues that linked fate may not mean the same thing for non-blacks as it does for blacks (Hochschild and Weaver 2015; Sanchez and Vargas 2016). Thus, I do not use the linked fate measure in analysis.

Because most of the ANES studies measure white identity and vote choice or candidate evaluations on the same survey waves, I account for the possibility that the measurement of white identity is influenced by these other items by also replicating the results from my 2016 analysis using a two-wave study fielded by YouGov in which white identity was measured on wave 1 and vote choice was measured on wave 2.

The distributions of racial resentment and white identity across the four surveys can be found in Online Appendix Fig. A1 and Table A1, respectively.

A race-of-interviewer variable was not avaialble for the 2016 ANES Time Series study at the time of this analysis.

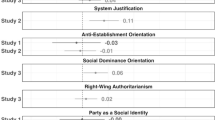

Results from the model are presented in table form in Online Appendix Table A2.

Following Kinder and Kalmoe (2017), I do not include political ideology in my main model specification given concerns that ideology often does not capture a meaningful set of attitudes. In Online Appendix Table A2, however, I show that my results are robust to controlling for ideology. I also demonstrate that the effects of white identity on vote choice are robust to controlling for other racial out-group attitudes, including the traditional anti-black stereotype index (as well as evaluations of two other salient racial and ethnic out-groups—Hispanics and Muslims—captured using 101-point thermometer items). Furthermore, I show that the results hold even after controlling for attitudes toward immigration—an issue that has become central to partisan politics in recent years, and which was deeply tied to Trump support (Abrajano and Hajnal 2015; Reny et al. 2019).

The New York Times compiled a list of Trump’s racist rhetoric and behavior: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/01/15/opinion/leonhardt-trump-racist.html.

In August of 2016, Forbes magazine noted that Clinton and Trump both promised to protect Social Security and Medicare https://www.forbes.com/sites/nextavenue/2016/08/08/social-security-where-clinton-and-trump-stand/#57c7c7e31904.

Some might wonder whether Cruz and Rubio, by way of their Hispanic ethnicity, might activate whites’ negative racial attitudes. This hypothesis is certainly possible, but both candidates notoriously down-play their ethnicity, meaning it might not have been especially salient to most voters.

In 2016, NPR published an article outlining Trump, Rubio, and Cruz’s positions on Social Security at https://www.npr.org/2016/03/12/470130961/fact-check-republican-candidates-on-keeping-or-changing-social-security.

Online Appendix Tables A3.1–A3.5 demonstrate the model’s robustness to inclusion of ideology and other out-group attitudes. The one exception is that the inclusion of the anti-Black stereotype index attenuates the relationship between white ID and Trump evaluations, but this effect is not surprising given that prior work has shown that the stereotype index is itself comprised of both in-group and out-group evaluations (Jardina 2019a, b).

Respondents were asked whether they preferred Jeb Bush, Ben Carson, Chris Christie, Ted Cruz, Carly Fiorina, John Kasich, Rand Paul, Marco Rubio, Donald Trump, another candidate, or none.

Appendix Table A4 presents the full estimation results and demonstrates the robustness of these results to including ideology, attitudes toward immigrants, and other measures of racial out-group attitudes.

Results of the full model are presented in appendix Table A5, which also demonstrates the robustness of the results to controls for ideology, other out-group attitudes, and immigration opinion.

I replicated these results using a two-wave panel study fielded by the survey firm YouGov. Wave 1 was fielded in October 2016, before the presidential election, and wave 2 was fielded after the election in November of 2016. White identity was measured on wave 1, and candidate evaluations were measured on wave 2. The results, presented in appendix Table A6, replicate the ANES results presented here, and provide confirmation that we can be confident that levels of white identity were not likely influenced by other survey questions measured on the same wave of the ANES studies.

Robustness checks are provided in appendix Table A7. Racial stereotype items were not available on 2018 ANES Pilot Study.

Analysis available upon request.

References

Abascal, M. (2015). Us and Them: Black–White Relations in the Wake of Hispanic Population Growth. American Sociological Review, 80(4), 789–813.

Abrajano, M., & Hajnal, Z. L. (2015). White Backlash: Immigration, Race, and American politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Blake, J. (2011). Are Whites Racially Oppressed? Atlanta, GA: CNN.

Blalock, H. M. (1967). Toward a theory of minority-group relations. New York: Wiley.

Blumer, H. (1958). Race prejudice as a sense of group position. The Pacific Sociological Review, 1(1), 3–7.

Bobo, L. D. (1983). Whites’ opposition to busing: Symbolic racism or realistic group conflict? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(6), 1196–1210.

Bobo, L. D., & Johnson, D. (2000). Racial attitudes in a prismatic metropolis: Mapping identity, stereotypes, competition, and views on affirmative action. In L. D. Bobo, M. L. Oliver, J. H. Johnson, Jr., & A. Valenzuela, Jr., (Eds.), Prismatic metropolis: Inequality in Los Angeles: A volume in the multi-city study of urban inequality (pp. 81–163). New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2010). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

Branscombe, N. R., Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (1999). The context and content of social identity threat. In N. Ellemers, R. Spears, & B. Doosje (Eds.), Social identity: Context, commitment, content (January) (pp. 35–58). Oxford: Blackwell.

Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., & Schiffhauer, K. (2007). Racial attitudes in response to thoughts of white privilege. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(2), 203–215.

Brewer, M. B. (1979). In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 86(2), 307–324.

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love or outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444.

Brewer, M. B., & Gaertner, S. L. (2004). Toward reduction of prejudice: Intergroup contact and social categorization. Self and Social Identity, 14398, 298–318.

Brimelow, P. (1996). Alien nation: Common sense about America’s immigration disaster. New York: HarperCollins.

Buchanan, P. J. (2011). Suicide of a superpower: Will America survive to 2025?. New York: Macmillan.

Budak, C., Goel, S., & Rao, J. M. (2016). Fair and balanced? Quantifying media bias through crowdsourced content analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(Special Issue 1), 250–271.

Citrin, J., & Sears, D. O. (2014). American identity and the politics of multiculturalism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Clawson, R. A., & Jett, J. (2019). The media whiteness of social security and medicare. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 7(1), 207–218.

Conover, P. J. (1984). The influence of group identifications on political perception and evaluation. Journal of Politics, 46(3), 760–785.

Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2014). More diverse yet less tolerant? How the increasingly-diverse racial landscape affects white Americans’ racial attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(6), 750–761.

Danbold, F., & Huo, Y. J. (2015). No longer ‘All-American’?: Whites’ defensive reactions to their numerical decline. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(2), 210–218.

Dawson, M. C. (1994). Behind the mule: Race and class in African-American politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dawson, M. C. (2009). Black and blue: Black identity and black solidarity in an era of conservative triumph. In R. Abdelal, Y. M. Herrera, A. I. Johnston, & R. McDermott (Eds.), Measuring identity: A guide for social scientists (pp. 175–199). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Doane, A. W. (1997). Dominant group ethnic identity in the United States: The role of ‘hidden’ ethnicity in intergroup relations. The Sociological Quarterly, 38(3), 375–397.

Edsall, T. B. (2012). Is Rush Limbaugh’s country gone ? The New York Times.

Frankenberg, R. (1993). White women, race matters: The social construction of whiteness. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Gibson, J. L. (2006). Do strong group identities fuel intolerance? Evidence from the South African case. Political Psychology, 27(5), 665–705.

Glaser, J. M. (1994). Back to the black belt: Racial environment and white racial attitudes in the south. The Journal of Politics, 56(1), 21–41.

Goren, M. J., & Plaut, V. C. (2012). Identity form matters: White racial identity and attitudes toward diversity. Self and Identity, 11(2), 237–254.

Guess, T. J. (2006). The social construction of whiteness: Racism by intent, racism by consequence. Critical Sociology, 32(4), 649–673.

Helms, J. E. (1995). An update of Helms’ white and people of color racial identity models. In J. G. Ponterotto, J. M. Casas, L. A. Suzuki, & C. M. Alexander (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 181–198). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Herring, M., Jankowski, T. B., & Brown, R. E. (1999). Pro-Black doesn’t mean anti-white: The structure of African-American group identity. Journal of Politics, 61(2), 363–386.

Hochschild, J., & Weaver, V. M. (2015). Is the significance of race declining in the political arena? Yes, and no. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(8), 1250–1257.

Huntington, S. P. (2004). Who are we? The challenges to America’s national identity. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Ingraham, C. (2016). Two new studies find racial anxiety is the biggest driver of support for Trump. The Washington Post.

Jardina, A. (2019a). White consciousness and white prejudice: Two compounding forces in contemporary American politics. The Forum, 17(3), 447–466.

Jardina, A. (2019b). White identity politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jardina, A., Kalmoe, N. P. & Gross, K. (2019). Disavowing white identity: How Trump’s election made white racial identity distasteful. In Paper pepared for The 2019 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington, DC.

Jardina, A., & Traugott, M. (2019). The Genesis of the Birther Rumor: Partisanship, racial attitudes, and political knowledge. Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics, 4(1), 60–80.

John, B. (2016). Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump voters share anger, but direct it differently. The New York Times.

Kam, C. D., & Kinder, D. R. (2012). Ethnocentrism as a short-term force in the 2008 American presidential election. American Journal of Political Science, 56(2), 326–340.

Key, V. O. (1949). Southern politics in state and nation. New York: Knopf.

Kinder, D. R., & Dale-Riddle, A. (2012). The end of race? Obama, 2008, and racial politics in America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Kalmoe, N. P. (2017). Neither liberal nor conservative: Ideological innocence in the American public. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Kiewiet, D. R. (1981). Sociotropic politics: The American case. British Journal of Political Science, 11(02), 129–161.

Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. M. (1996). Divided by color: Racial politics and democratic ideals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Sears, D. O. (2013). Prejudice and politics: Symbolic racism versus racial threats to the good life. In L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, & J. S. Levy (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 414–431). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Winter, N. J. G. (2001). Exploring the racial divide: Blacks, whites, and opinion on national policy. American Journal of Political Science, 45(2), 439–456.

Knowles, E. D., & Peng, K. (2005). White selves: Conceptualizing and measuring a dominant-group identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(2), 223–241.

LoGiurato, B. (2012). Bill O’Reilly goes off: ‘The white establishment is the minority.’ Business Insider.

Major, B., Blodorn, A., & Blascovich, G. M. (2016). The threat of increasing diversity: Why many White Americans support Trump in the 2016 presidential election. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(6), 931–940.

McClain, P. D., Carew, J. J., Walton, E., Jr., & Watts, C. S. (2009). Group membership, group identity, and group consciousness: Measures of racial identity in American politics? Annual Review of Political Science, 12(1), 471–485.

Mendelberg, T. (2001). The race card: Campaign strategy, implicit messages, and the norm of equality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Miller, A. H., Gurin, P., Gurin, G., & Malanchuk, O. (1981). Group consciousness and political participation. American Journal of Political Science, 25(3), 494–511.

Oliver, J. E., & Mendelberg, T. (2000). Reconsidering the environmental determinants of white racial attitudes. American Journal of Political Science, 44(3), 574–589.

Ostfeld, M. C. (2019). The new white flight? The effects of political appeals to Latinos on white democrats. Political Behavior, 41(3), 561–582.

Outten, H. R., Schmitt, M. T., Miller, D. A., & Garcia, A. L. (2012). Feeling threatened about the future: Whites’ emotional reactions to anticipated ethnic demographic changes. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(1), 14–25.

Pasek, J., Stark, T. H., Krosnick, J. A., & Tompson, T. (2015). What motivates a conspiracy theory? Birther beliefs, partisanship, liberal-conservative ideology, and anti-black attitudes. Electoral Studies, 40, 482–489.

Petrow, G. A., Transue, J. E., & Vercellotti, T. (2018). Do white in-group processes matter, too? White racial identity and support for black political candidates. Political Behavior, 40(1), 197–222.

Piston, S. (2010). How explicit racial prejudice hurt Obama in the 2008 election. Political Behavior, 32(4), 431–451.

Reny, T. T., Collingwood, L., & Valenzuela, A. A. (2019). Vote switching in the 2016 election: How racial attitudes and immigration attitudes, not economics, explain shifts in white voting. Public Opinion Quarterly, 83(1), 91–113.

Rivers, D. (2006). Polimetrix white paper series. Sample matching: Representative sampling from internet panels.

Sanchez, G. R., & Vargas, E. D. (2016). Taking a closer look at group identity: The link between theory and measurement of group consciousness and linked fate. Political Research Quarterly, 69(1), 160–174.

Schildkraut, D. J. (2015). White attitudes about descriptive representation in the US: The roles of identity, discrimination, and linked fate. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 5(1), 84–106.

Sears, D. O. (1993). Symbolic politics: A socio-psychological theory. In S. Iyengar & W. J. McGuire (Eds.), Explorations in political psychology (pp. 113–149). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Sears, D. O., & Savalei, V. (2006). The political color line in America: many ‘peoples of color’ or black exceptionalism? Political Psychology, 27(6), 895–924.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sides, J., Tesler, M., & Vavreck, L. (2018). Identity crisis: The 2016 presidential campaign and the battle for the meaning of America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sniderman, P. M., & Carmines, E. G. (1997). Reaching beyond race. Political Science & Politics, 30(3), 466–471.

Struch, N., & Schwartz, S. H. (1989). Intergroup aggression: Its predictors and distinctness from in-group bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(3), 364–373.

Sumner, W. G. (1906). Folkways: A study of the sociological importance of usages, manners, customs, mores, and morals. Boston: Ginn.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149–178.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Monterrey: Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.

Tesler, M. (2015). How anti-immigrant attitudes are fueling support for Donald Trump. The Washington Post Monkey Cage.

Tesler, M. (2016). Post-racial or most-racial? Race and politics in the Obama era. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Tesler, M., & Sears, D. O. (2010). Obama’s race: The 2008 election and the dream of a post-racial America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tesler, M. & Sides, J. (2016). How political science helps explain the rise of Trump: The role of white identity and grievances. The Washington Post.

Valentino, N. A., Hutchings, V. L., & White, I. K. (2002). Cues that matter: How political ads prime racial attitudes during campaigns. American Political Science Review, 96(1), 75–90.

Valentino, N. A., Neuner, F. G., & Vandenbroek, L. M. (2018). The changing norms of racial political rhetoric and the end of racial priming. The Journal of Politics, 80(3), 757–771.

Winter, N. J. G. (2006). Beyond welfare: Framing and the racialization of white opinion on social security. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 400–420.

Wong, C., & Cho, G. (2005). Two-headed coins or kandinskys: White racial identification. Political Psychology, 26(5), 699–720.

Acknowledgements

I thank Ted Brader, Vincent Hutchings, Spencer Piston, Ismail White, Nathan Kalmoe, Alexander Von Hagen-Jamar, and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jardina, A. In-Group Love and Out-Group Hate: White Racial Attitudes in Contemporary U.S. Elections. Polit Behav 43, 1535–1559 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09600-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09600-x