Abstract

According to conventional wisdom in political behavior research, education has a direct causal effect on political participation. However, a number of recent studies have questioned this established view by arguing that education is not a direct cause of political participation but only a proxy for other factors that are not directly related to the educational experience. This paper engages in a current debate regarding the application of matching techniques to assess whether there is a direct causal effect of education on political participation. It uses data from a British cohort study that follows everyone born during 1 week in the UK in 1970. The data includes a rich set of variables measuring factors through childhood and adolescence such as cognitive ability and family socioeconomic status. This data provides the opportunity to match on a number of important variables that are not included in the US datasets used by previous studies in the field. Results show that after matching there are no significant effects of education on political participation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

An alternative theoretical model, which also considers education to be a proxy, is presented by the sorting model of education effects (Nie et al. 1996; Campbell 2009; Persson 2011, 2013). According to this model, education has no value per se but rather serves as a proxy for social network position.

When analyzing the data used in this paper with propensity score matching results show significantly worse balance than for genetic matching. Moreover, coarsened exact matching leaves too many treated observations unmatched.

An alternative causal estimate is the average treatment effect for the controls (ATC). The main difference between the ATT and the ATC is that when estimating the ATC, the comparison is conditioned on the covariate distribution among the untreated. Hence, rather than evaluating whether education has a causal effect on those who received it (the ATT measure), the ATC evaluates a hypothetical counterfactual state in which untreated individuals would receive higher education. I follow Kam and Palmer (2008, 2011) in their interpretation of the literature as I am primarily concerned with whether education has a causal effect among those who actually received it, rather than what the effect would be if higher education were given to a random person not receiving it. Hence, if we are interested in whether education had any causal effect among those receiving it, the ATT is the primary relevant estimate.

Information about the 1970 British Cohort Study is available at http://www.cls.ioe.ac.uk/.

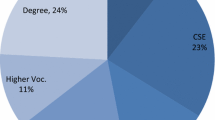

As for the treatment variable some dichotomization is necessary because of the restrictions of the available matching algorithms and software. Moreover, college education is the level of education that is largely considered to be a figurative step in people’s lives. Research on educational attainment describes college education as a “key transition” that has more explanatory power than, for example, cumulative years of education (cf. Kam and Palmer 2008). Additional analyses on data from the 1970 British Cohort Study confirm that college education is the most important educational level in relation to political participation. Participation levels are always significantly higher for individuals with college education than for individuals with all lower educational levels. Further, in regards to contact with politicians, and attending rallies and demonstrations, there is no significant difference between persons with no education and persons who have completed high school/secondary school; the significant difference is between those with higher education and those with lower levels of education.

The full questionnaires including the cognitive ability test can be found at http://www.cls.ioe.ac.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=142&itemtype=document.

Previous studies have used the summary scale of these indices as a proxy for IQ (Elliott et al. 1978). Following Deary et al. (2008), I construct a variable consisting of the scores on the first unrotated component and convert it to a traditional IQ scale with a mean of 100 and SD of 15. I use this measure to check for balance, see the online appendix for further details.

The problem of attrition out of the panel is difficult to address. Particularly troublesome is that low cognitive ability persons drop out of the panel to a higher degree. If setting the mean on the summary scales of the cognitive ability variables to 100 with a SD of 15 for the entire sample that answered these questions, the mean for those who participate in the 2004 survey are 101.7 (age 10 cognitive ability) and 101.2 (age 5 cognitive ability), a relatively small but statistically significant difference. Since non-graduates are less likely to answer the survey, it might be the case that the non-college attenders in the sample are more educated and have higher cognitive ability than the non-college attenders in the population. The low educated in the dataset may plausibly be participating more than the true population of people without college degrees. This would mean that the differences between college graduates and non-college graduates are underestimated in the dataset.

As for the item non-responses, I have checked among the 45% of the sample that made it to the 2004 survey to determine whether a binary indicator for deleted or not deleted, due to item non-response, is balanced across persons with college degrees and without college degrees (for each covariate used in the matching procedure). T test and Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) test p-values indicate that most covariates are balanced across educational groups. However, significant differences in the amount of non-responses are found for family income 1986, parents’ education 1970, and the cognitive ability scores (except for the profile test). As for family income 1986, the differences in item non-responses between college educated and non-college educated is five percentage points. For the other covariates, differences in item non-responses are not higher than two percentage points.

A potential problem is that education is correlated with panel attrition. Among people who had graduated from college and responded to the survey in 2000, 85 % participated in 2004. The corresponding number was 79 % for the non-graduates. In 2008, 81 % of those with a college degree in the year 2000 participated in the survey, while only 70 % of the year 2000 non-graduates.

A comparison of the means for the matching covariates in the full 2004 dataset, with only the respondents in the balanced dataset, containing only those who participated in all previous waves, show small differences of means. All differences of means are less than 1/10 of a standard deviation. This is also the case within the sub-groups of those with and without higher education. For more information on the non-responses see, McDonald and others (2010). Non-responses were not missing at random: “Response was lower for cohort members who were men, having a mother who was younger at the birth, a mother who did not attempt to breastfeed, a lower birth weight baby, in a family with two or more children, born of non-married parents, a manual father and living in London” (McDonald and others 2010, 26). However, interest in politics was not found to be associated with non-response. This means that the population that this sample represents differs slightly from the total population and is biased towards the groups with high response rates mentioned above. Still, it should be acknowledged that the panel attrition rate is high and this should be taken into account when interpreting the results.

The matching has been carried out with the GenMatch package in R.

Table 1 in the online appendix presents results from the balance tests of the items that are used to construct the summary scales used for the matching procedure, as well as, the summary scales for cognitive ability at ages 5 and 10. While most covariates are unbalanced before matching, balance is achieved after matching (all K–S p-values indicate non-significant differences).

Figure 1 in online appendix presents standardized bias before and after matching for all items that are utilized to construct the summary scales used for the matching procedure, as well as, the summary scales for cognitive ability at ages 5 and 10. While most covariates are unbalanced before matching, only two covariates fall outside the confidence bounds after matching.

A further concern could be that the results are an artifact of the specific matching routine applied (1:1 with replacement). Replacement refers to whether a matched observation can be used again for another match. Tables 2 and 3 in online appendix report ATT estimates from genetic matching 1:2 with replacement (each treated matched to two untreated), as well as 1:1 and 1:2, without replacement. The results from 1:2 matching with replacement show no significant differences. However, estimates from matching without replacement show several significant differences in political participation between those with higher education and those without, in particular estimates derived after 1:2 matching. But since it is harder to achieve balance without replacement, and balance decreases as more untreated observations are matched with treated observations, we should not put too much confidence in these results.

A drawback of these measures is that this particular survey had an unusually low response rate. Hence, the number of persons with college education and responses on all relevant variables is reduced to 401.

References

Achen, C. H. (2002). Parental socialization and rational party identification. Political Behavior, 24, 151–170.

Akerhielm, K., Berger, J., Hooker, M., & Wise, D. (1998). Factors related to college enrollment: Final report. Washington, DC: US Department of Education.

Andolina, M. W., Jenkins, K., Zukin, C., & Keeter, S. (2003). Habits from home, lessons from school: Influences on youth civic development. PS: Political Science and Politics, 36, 275–280.

Bartels, M., Rietveld, M. J. H., Van Baal, G. C. M., & Boomsma, D. I. (2002). Heritability of educational achievement in 12-year-olds and the overlap with cognitive ability. Twin Research, 5, 544–553.

Belley, P., & Lochner, L. (2007). The changing role of family income and ability in determining educational achievement. Journal of Human Capital, 1, 37–89.

Berinsky, A. J., & Lenz, G. S. (2011). Education and political participation: Exploring the causal link. Political Behavior, 33, 357–373.

Bernstein, R., Chadha, A., & Montjoy, R. (2001). Overreporting voting: Why it happens and why it matters. Public Opinion Quarterly, 65, 22–44.

Blanden, J., Gregg, P., & Machin, S. (2005). Intergenerational Mobility in Europe and North America. London: LSE Centre for Economic Performance.

Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. (2001). Class, mobility and merit: The experience of two British cohorts. European Sociological Review, 17, 81–101.

Brimer, M. A., & Dunn, L. M. (1968). English picture vocabulary test. Newham: Educational Evaluation Enterprises.

Burden, B. (2009). The dynamic effects of education on voter turnout. Electoral Studies, 28, 540–549.

Campbell, D. E. (2006). What is education’s impact on civic and social engagement. In R. Desjardins & T. Schuller (Eds.), Measuring the effects of education on health and civic engagement (pp. 25–126). Paris: OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation.

Campbell, D. E. (2009). Civic engagement and education: an empirical test of the sorting model. American Journal of Political Science, 53, 771–786.

Chevalier, A., & Lanot, G. (2002). The relative effect of family characteristics and financial situation on educational achievement. Education Economics, 10, 165–181.

Converse, P. E. (1972). Change in the American electorate. In A. Campbell & P. E. Converse (Eds.), The human meaning of social change (pp. 263–337). New York: Russell Sage.

Davie, R., Butler, N., & Goldstein, H. (1972). From birth to seven. London: Longmans.

Dinesen, P.T., Dawes, C. T., Johanneson, M., Klemmensen, R., Magnusson, P.K.E., Sonne Nørgaard, A., Pedersen, I., & Oskarsson, S. (2012) Estimating the causal impact of education on political engagement: Evidence from monozygotic twins in the United States, Denmark and Sweden. Paper presented at APSA 2012.

Deary, I. J., Batty, G. D., & Gale, C. R. (2008). Childhood intelligence predicts voter turnout, voting preferences and political involvement in adulthood: The 1970 British Cohort Study. Intelligence, 36, 548–555.

Deary, I. J., Strand, S., Smith, P., & Fernandes, C. (2007). Intelligence and educational achievement. Intelligence, 35, 13–21.

Dee, T. S. (2004). Are there civic returns to education? Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1697–1720.

Dehejia, R. H., & Wahba, S. (2002). Propensity score matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84, 151–161.

Denny, K., & Doyle, O. (2008). Political interest, cognitive ability and personality: Determinants of voter turnout in Britain. British Journal of Political Studies, 38, 291–310.

Diamond, A., & Sekhon, J. S. (2012). Genetic matching for estimating causal effects: A general multivariate matching method for achieving balance in observational studies. Paper available at http://sekhon.berkeley.edu/papers/GenMatch.pdf. Accessed 12 Sep 2013.

Elliott, C., Murray, D., & Pearson, L. (1978). British ability scales. Windsor: National Foundation for Educational Research.

Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2007). Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Granberg, D., & Holmberg, S. (1991). Self-reported turnout and voter validation. American Journal of Political Science, 35, 448–459.

Hansen, B. B. (2004). Full matching in an observational study of coaching for the SAT. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 99, 609–618.

Harris, D. (1963). Children’s drawings as measures of intellectual maturity. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Henderson, J., & Chatfield, S. (2011). Who matches? Propensity scores and bias in the causal effects of education on participation. Journal of Politics, 73, 646–658.

Highton, B. (2009). Revisiting the relationship between educational attainment and political sophistication. Journal of Politics, 71, 1564–1576.

Holland, P. W. (1986). Statistics and causal inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 81, 945–960.

Iacus, S. M., King, G., & Porro, G. (2012). Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis, 20, 1–24.

Imai, K., King, G., & Stuart, E. (2008). Misunderstandings among experimentalists and observationalists about causal inference. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 171, 481–502.

Jackson, R. A. (1995). Clarifying the relationship between education and turnout. American Politics Research, 23, 279–299.

Jennings, K. M., & Niemi, R. G. (1974). The political character of adolescence: the influence of families and schools. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kam, C. D., & Palmer, C. L. (2008). Reconsidering the effects of education on political participation. Journal of Politics, 70, 612–631.

Kam, C. D., & Palmer, C. L. (2011). Rejoinder: Reinvestigating the causal relationship between higher education and political participation. Journal of Politics, 73, 659–663.

Ketende, S.C., McDonald, J. & Dex, S. (2010). Non-response in the 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70) from birth to 34 years. Centre for Longitudinal Studies: Working paper 2010/4.

Klasik, D. (2012). The college application gauntlet: A systematic analysis of the steps to four-year college enrollment. Research in Higher Education, 53, 506–549.

Langton, K. P., & Jennings, K. M. (1968). Political socialization and the high school civics curriculum in the United States. American Political Science Review, 62, 852–867.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Jacoby, W. G., Norpoth, H., & Weisberg, H. F. (2008). The American voter revisited. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Lijphart, A. (1997). Unequal participation: Democracy’s unresolved dilemma. American Political Science Review, 91, 1–14.

Luskin, R. C. (1990). Explaining political sophistication. Political Behavior, 12, 331–361.

Mayer, A. K. (2011). Does education increase political participation? Journal of Politics, 73, 633–645.

Milligan, K., Moretti, E., & Oreopoulos, P. (2004). Does education improve citizenship? Evidence from the United States and the United Kingdom. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1667–1695.

Morgan, S. L., & Winship, C. (2007). Counterfactuals and causal inference: methods and principles for social research. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Nie, N., Junn, J., & Stehlik-Barry, K. (1996). Education and democratic citizenship in America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Pelkonen, P. (2012). Length of compulsory education and voter turnout—evidence from a staged reform. Public Choice, 150, 51–75.

Persson, M. (2011). An empirical test of the relative education model in Sweden. Political Behavior, 33, 455–478.

Persson, M. (2012). Does type of education affect political participation? Results from a panel survey of Swedish adolescents. Scandinavian Political Studies, 35, 198–221.

Persson, M. (2013). Is the effect of education on voter turnout absolute or relative? A multi-level analysis of 37 countries. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 23, 111–133.

Persson, M., & Oscarsson, H. (2010). Did the egalitarian reforms of the Swedish educational system equalise levels of democratic citizenship? Scandinavian Political Studies, 33, 135–163.

Rindermann, H., Flores-Mandoza, C., & Woodley, A. (2012). Political orientations, intelligence and education. Intelligence, 40, 217–225.

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70, 41–55.

Rubin, D. B. (1973). Matching to remove bias in observational studies. Biometrics, 29, 159–183.

Rubin, D. B. (1974). Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 66, 688–701.

Scott, L. (1968). Measuring intelligence with the Goodenough–Harris drawing test. Psychological Bulletin, 89, 483–505.

Searing, D., Wright, G., & Rabinowitz, G. (1976). The primacy principle: Attitude change and political socialization. British Journal of Political Science, 6, 83–113.

Sears, D. O., & Funk, C. L. (1999). Evidence of the long-term persistence of adults’ political predispositions. Journal of Politics, 61, 1–28.

Sekhon, J. S. (2011). Multivariate and propensity score matching software with auto-mated balance optimization. Journal of Statistical Software, 42, 1–52.

Sondheimer, R. M., & Green, D. P. (2010). Using experiments to estimate the effects of education on voter turnout. American Journal of Political Science, 54, 174–189.

Sternberg, R. J., Grigorenko, E. L., & Bundy, D. A. (2001). The predictive value of IQ. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 47, 1–41.

Tenn, S. (2005). An alternative measure of relative education to explain voter turnout. Journal of Politics, 67, 271–282.

Tenn, S. (2007). The effect of education on voter turnout. Political Analysis, 15, 446–464.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Westholm, A. (1999). The perceptual pathway: Tracing the mechanisms of political value transfer across generations. Political Psychology, 20, 525–551.

Wolfinger, R. E., & Rosenstone, S. J. (1980). Who votes?. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Acknowledgments

I thank Debbie Axlid, Peter Thisted Dinesen, Peter Esaiasson, Mikael Gilljam, Henrik Oscarsson, Sven Oskarsson, Zethyn Ruby, three anonymous reviewers, the editors of Political Behavior, and seminar participants at University of Copenhagen, Lund University, Uppsala University, the MPSA 2012 and the EPOP 2012 meetings for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Persson, M. Testing the Relationship Between Education and Political Participation Using the 1970 British Cohort Study. Polit Behav 36, 877–897 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9254-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9254-0