Abstract

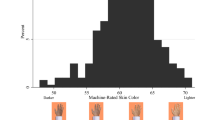

Despite the significant role that skin color plays in material well-being and social perceptions, scholars know little if anything about whether skin color and afrocentric features influence political cognition and behavior and specifically, if intraracial variation in addition to categorical difference affects the choices of voters. Do more phenotypically black minorities suffer an electoral penalty as they do in most aspects of life? This study investigates the impact of color and phenotypically black facial features on candidate evaluation, using a nationally representative survey experiment of over 2000 whites. Subjects were randomly assigned to campaign literature of two opposing candidates, in which the race, skin color and features, and issue stance of candidates was varied. I find that afrocentric phenotype is an important, albeit hidden, form of bias in racial attitudes and that the importance of race on candidate evaluation depends largely on skin color and afrocentric features. However, like other racial cues, color and black phenotype don’t influence voters’ evaluations uniformly but vary in magnitude and direction across the gender and partisan makeup of the electorate in theoretically explicable ways. Ultimately, I argue, scholars of race politics, implicit racial bias, and minority candidates are missing an important aspect of racial bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“Did GOP Ad darken skin-color of Indian-American dem candidate?” Huffington post, October 30, 2008. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2008/10/30/did-gop-ad-darken-skin-co_n_139182.html.

“Obama skin tone darker in Clinton Ad?” Huffington post, March 4, 2008. Available at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2008/03/04/obama-skin-tone-darker-in_n_89829.html.

Lighter-skinned blacks often inherited better opportunities and status; often, however, disparities in socioeconomic wellbeing persist even after accounting for differences in family class background, suggesting a direct influence of color on outcomes. For a comprehensive exploration of color disparities and colorism than space allows here, see Nance 2005 and Hunter 2007.

While not enjoying a better legal status, lighter-skinned and mixed-race blacks often enjoyed substantial advantages since at least the first Reconstruction in both the black and white communities. Lighter-skinned black soldiers were more likely to be promoted in the Civil War; lighter-skinned blacks had superior educational arrangements; and fairer blacks were more likely to be a member of the black elite and leadership. For a comprehensive discussion, see Jones 2000.

While skin color discrimination is technically proscribed under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, the Court has said: “there is no basis on this record for the recognition of skin color as a presumptive discriminatory criterion” (quoting Supreme Court in Nance 2005, p. 460). One defendant in a color lawsuit, the IRS, argued that there couldn’t be discrimination because “skin color and race are essentially the same characteristic” (Nance 2005, p. 465).

A disproportionate number of high-ranking appointments to blacks have favored the lighter of the race. In a study of black politicians since the passage of the Voting Rights Act, color had only a weak association with running for office but black candidates with lighter skin were more likely to ultimately be elected (Hochschild and Weaver 2007, p. 651). So while the VRA produced more descriptive representation for blacks, it was accompanied by the underrepresentation of darker-skinned blacks. Color-based electoral disadvantage has been more directly explored outside the United States; two economists analyzed elections in Australia (where photographs of candidates were required to appear on the ballot) and found that “the aspect of the candidate’s appearance that matters most is not beauty, but skin color” (Leigh and Susilo 2009, p. 62). In non-indigenous electorates, vote share declined significantly with darker skin for both challengers and incumbents.

While its invisibility in political discourse likely masks its role in politics, at least a few campaigns have recognized its potential to affect the subconscious evaluations of voters, including several examples of deliberate attempts at exaggerating the dark color of opponents in visual campaign material in competitive races. Skin color has also been displayed in the opposite direction—not to make one’s black opponent more menacing, but in same-race electoral contests as a symbol of upper-class roots and racial inauthenticity. Color appeals were featured prominently in several recent races, including the Newark mayoral contest between Sharpe James and Corey Booker, the election between Earl Hilliard and Artur Davis for the 7th Congressional district in Alabama, and the mayoral election in Washington, DC between Sharon Pratt Kelley and Marion Barry; in each of these contests, the first candidate made references to their opponents’ fairer skin shade in order to call into question their racial authenticity and suggest an out-of-touch bourgeoisie background, thereby discrediting their ability to relate to the “people.”

The Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (TESS) administers a random internet sample, which is currently gathered through Knowledge Networks, a company that specializes in providing representative samples that are interviewed via WebTV. From the TESS website www.experimentcentral.org: “To achieve a representative sample, Knowledge Networks … uses a random RDD sample. When a person agrees to participate, they are provided with free Internet access (via WebTV) and are given the necessary hardware for as long as they remain in the sample. Most research to date comparing this kind of sample with telephone RDD samples suggest they are equally representative, and some suggest that the data obtained via WebTV/internet are somewhat more reliable than what is obtained by phone.”

I am very interested in whether and how respondents of different races and ethnicities respond to candidate skin color, and whether they follow the same pattern as whites. By restricting the study to non-Hispanic white respondents, the author does not mean to imply that the race and skin color of political candidates does not influence evaluations for black and Latino voters. To make an analysis of minority reactions feasible across a 16 cell design, however, required a very large oversample of Blacks and Latinos, which I was not able to obtain.

Candidate issue stances were modified versions of real candidate positions taken from campaign websites. Candidate platforms available upon request (Supplementary Material).

The candidates are purposefully not given an explicit party label, Democrat or Republican, for two major reasons. First, this label will mean different things in different regions, such that using a conservative/liberal platform dichotomy is more informative and easier to analyze. Second, prior studies have also avoided party labels because of their potential to “swamp” the results and given the fact that most real-world candidates do not explicitly mention their party on campaign ads (Berinsky and Mendelberg 2005). The conservative/liberal platform manipulation was effective. On average respondents did perceive a difference in the candidate platforms; on a scale from 1 to 7, with 1 being “extremely liberal” and 7 being “extremely conservative” the liberal candidate received an average rating that falls on the liberal side of the scale (3.5) and the conservative candidate received an average score more towards the conservative side of the scale (4.4).

It is possible that subjects see the light-skinned black candidate as biracial, racially ambiguous, or “less black” than the dark-skinned black. However, the manipulation check demonstrates that there is widespread agreement that the light-skinned candidate is black.

The questions were carefully designed and pretested in two pilot studies. Where possible, these questions are directly taken from, or closely resemble, survey items in the American National Election Studies (ANES). Survey questionnaire available upon request (Supplementary Material).

The racial predisposition question is asked separately and later in the survey module so as not to prime subjects or clue them into the nature of the study (Mendelberg 2008b).

Models have been tested with and without controls included; results do not depend on the inclusion of controls. Results without control variables are available from the author.

This measure is constructed as the difference between the ideological score subjects gave the candidate and the opponent on a standard 7-point ideology item. The measure goes from −6 to 6, such that a negative number indicates the subject rated the White1 candidate as more conservative and a positive number indicates they rated the opponent as more conservative; 0 = no difference.

Subjects were not significantly more likely to rate the dark-skinned black candidate as more hardworking or trustworthy when the light-skinned black condition was the baseline. Subjects were significantly less likely to rate the light-skinned black as intelligent and experienced compared to both the control and when the dark-skinned black was the baseline comparison group.

While these differences are statistically significant compared to the control, results for the dark-skinned black are not statistically significant when the light-skinned black condition is the baseline (except for intelligent).

The ideology measure was the traditional 7-point item from extremely conservative to extremely liberal. This was further collapsed so that respondents on the conservative side of the scale were coded as 1, moderates as 0, and liberals as −1. I have run the analysis using both versions of this measure and the results do not depend on whether the collapsed or original measure is used.

Interactions by age, region, urbanicity, education, and income did not have a clear or significant impact. Following Kuklinski and his colleagues, I examined an interaction for southern men and for respondents born before 1960 but there was no effect (1997).

For reasons unknown, women are more likely to support White2 in the control condition than men.

The same basic results obtain if I use party identification instead of political ideology. Republicans, like conservatives, are significantly less likely to vote for the dark-skinned black opponent. Though partisanship and ideology are not the same, I report results for ideology with the caveat that the same pattern of results obtains for partisanship.

For space considerations, these separate models are not reported. Full tables are available by request.

References

Allen, W., Telles, E., & Hunter, M. (2000). Skin color, income, and education: A comparison of African Americans and Mexican Americans. National Journal of Sociology, 12(1), 129–180.

Berinsky, A. J., & Mendelberg, T. (2005). The indirect effects of discredited stereotypes in judgments of Jewish Leaders. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 845–864.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2003). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. NBER working paper no. W9873. http://ssrn.com/abstract=428367.

Blair, I., Judd, C., & Chapleau, K. (2004). The influence of afrocentric facial features in criminal sentencing. Psychological Science, 15(10), 674–679.

Bowman, P., Muhammad, R., & Ifatunji, M. (2004). Skin tone, class, and racial attitudes among African Americans. In C. Herring, V. Keith, & H. Horton (Eds.), Skin deep: How race and complexion matter in the ‘color-blind’ era (pp. 128–158). Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Burton, L. M., Bonilla-Silva, E., Ray, V., Buckelew, R., & Freeman, E. H. (2010). Critical race theories, colorism, and the decade’s research on families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 440–459.

Butler, D. M., & Broockman, D. E. (2009). Who helps DeShawn register to vote? A field experiment on state legislators. Unpublished paper. https://harrisschool.uchicago.edu/programs/beyond/workshops/ampolpapers/fall09-butler.pdf.

Callaghan, K., & Terkildsen, N. (2002). Understanding the role of race in candidate evaluation. Political Decision Making, Deliberation and Participation, 6, 51–95.

Citrin, J., Green, D. P., & Sears, D. O. (1990). White reactions to black candidates: When does race matter? Public Opinion Quarterly, 54(1), 74–96.

Colleau, S. M., et al. (1990). Symbolic racism in candidate evaluation: An experiment. Political Behavior, 12(4), 1573–6687.

Dasgupta, N., Banaji, M. R., & Abelson, R. P. (1999). Group entitativity and group perception: Associations between physical features and psychological judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(5), 991–1003.

Dixon, T. L., & Maddox, K. B. (2005). Skin tone, crime news, and social reality judgments: Priming the stereotype of the dark and dangerous Black criminal. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(8), 1555–1570.

Eberhardt, J., Davies, P., Purdie-Vaughns, V., & Johnson, S. (2006). Looking deathworthy: Perceived stereotypicality of Black defendants predicts capital sentencing outcomes. Psychological Science, 17(5), 383–386.

Eberhardt, J. L., Goff, P. A., Purdie, V. J., & Davies, P. G. (2004). Seeing Black: Race, crime, and visual processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 876–893.

Figlio, D. N. (2005). Names, Expectations and the Black-White test score gap. NBER working paper series, Vol. w11195.

Friedman, S., Gregory, D. S., & Chris G. (2010). Cybersegregation in Boston and Dallas: Is Neil a more desirable tenant than Tyrone or Jorge? Unpublished paper. http://mumford.albany.edu/mumford/Cybersegregation/friedmansquiresgalvan.May2010.pdf.

Fryer, R. G. Jr., & Levitt, S. (2004). The causes and consequences of distinctively black names. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(3), 767–805.

Goldsmith, A. H., Hamilton, D., & Darity, W., Jr. (2007). From dark to light: Skin color and wages among African-Americans. Journal of Human Resources, 42(4), 701–738.

Gyimah-Brempong, K., & Price, G. N. (2006). Crime and punishment: And skin hue too? American Economic Review, 96(2), 246–250.

Harburg, E., Gleibermann, L., Roeper, P., Anthony Schork, M., & Schull, W. J. (1978). Skin color, ethnicity, and blood pressure I: Detroit Blacks. American Journal of Public Health, 68(12), 1177–1183.

Harris, A. P. (2008). From color line to color chart?: Racism and colorism in the new century. Berkeley Journal of African-American Law and Policy, 10(1), 52–69.

Hersch, J. (2006). Skin-tone effects among African Americans: Perceptions and reality. American Economic Review, 96(2), 251–255.

Highton, B. (2004). White voters and African American candidates for congress. Political Behavior, 26(1), 1–25.

Hill, M. E. (2000). Color differences in the socioeconomic status of African American men: Results of a longitudinal study. Social Forces, 78(4), 1437–1460.

Hochschild, J., & Weaver, V. (2007). The skin color paradox and the American racial order. Social Forces, 86(2), 643–670.

Hollinger, D. A. (2003). Amalgamation and hypodescent: The question of ethnoracial mixture in the history of the United States. American Historical Review, 108(5), 1363–1390.

Hughes, M., & Hertel, B. (1990). The significance of color remains: A study of life chances, mate selection, and ethnic consciousness among Black Americans. Social Forces, 68(4), 1105–1120.

Hunter, M. (2007). The persistent problem of colorism: Skin tone, status, and inequality. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 237–254.

Hurwitz, J., & Peffley, M. (1997). Public perceptions of race and crime: The role of racial stereotypes. American Journal of Political Science, 41(2), 375–401.

Hutchings, V. L., Hanes W., Jr., & Andrea B. (2005). Heritage or hate? Race, gender, partisanship & the Georgia state flag controversy. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Washington, DC.

Hutchings, V. L., Valentino, N. A., Philpot, T. S., & White, I. K. (2004). The compassion strategy: Race and the gender gap in campaign 2000. Public Opinion Quarterly, 68(4), 512–541.

Iyengar, S. & Kyu, S. H. (2007). Natural disasters in Black and White: How racial cues influenced public response to Hurricane Katrina. Unpublished paper.

Johnson, J. J., Farrell, W. J., & Stoloff, J. (1998). The declining social and economic fortunes of African American males: A critical assessment of four perspectives. Review of Black Political Economy, 25(4), 17–40.

Jones, T. (2000). Shades of Brown: The law of skin color. Duke Law School, public law working paper no. 7.

Jones, C. E., & Clemons, M. L. (1993). A model of racial crossover voting: An assessment of the wilder victory. In G. Persons (Ed.), Dilemmas of black politics: Issues of leadership and strategy. New York: Harper Collins.

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 339–375.

Keith, V., & Herring, C. (1991). Skin tone and stratification in the Black Community. American Journal of Sociology, 97(3), 760–778.

King, E. B., Mendoza, S. A., Madera, J. M., Hebl, M. R., & Knight, J. L. (2006). What’s in a name? A multiracial investigation of the role of occupational stereotypes in selection decisions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(5), 1145–1159.

King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: Improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2), 347–361.

Klonoff, E. A., & Landrine, H. (2000). Is skin color a marker for racial discrimination? Explaining the skin color-hypertension relationship. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23(4), 329–338.

Krieger, N., Sidney, S., & Coakley, E. (1998). Racial discrimination and skin color in the CARDIA study: Implications for public health research. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 1308–1313.

Kuklinski, J. H., Cobb, M. D., & Gilens, M. (1997). Racial attitudes and the ‘New South’. Journal of Politics, 59(2), 323–349.

Leigh, A., & Susilo, T. (2009). Is voting skin-deep? Estimating the effect of candidate ballot photographs on election outcomes. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(1), 61–70.

Maddox, K. B., & Gray, S. (2002). Cognitive representations of Black Americans: Reexploring the role of skin tone. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(2), 250–259.

Massey, D. S., & Lundy, G. (2001). Use of Black english and racial discrimination in urban housing markets: New methods and findings. Urban Affairs Review, 36, 470–496.

McDermott, M. (1998). Race and gender cues in low-information elections. Political Research Quarterly, 51(4), 895–918.

Mendelberg, T. (2008a). Racial priming revived. Perspectives on Politics, 6(1), 109–123.

Mendelberg, T. (2008b). Racial priming: Issues in research design and interpretation. Perspectives on Politics, 6(1), 135–140.

Messing, S., Ethan P., & Maria J. (2009). Bias in the flesh: Attack Ads in the 2008 presidential campaign. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Toronto, Canada.

Moskowitz, D., & Stroh, P. (1994). Psychological sources of electoral racism. Political Psychology, 15(2), 307–329.

Nance, C. E. (2005). Colorable claims: The continuing significance of color under title VII forty years after its passage. Berkeley Journal of Employment and Labor Law, 26, 435–474.

Nosek, B. A., Mahzarin R. B., & John T. J. (2009). The politics of intergroup attitudes. In J.T. Jost, A.C. Kay, & H. Torisdottir (Eds.), The social and psychological bases of ideology and system justification. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Nosek, B., et al. (2007). Pervasiveness and correlates of implicit attitudes and stereotypes. European Review of Social Psychology, 18, 36–88.

Pratto, F., Stallworth, L. M., & Sidanius, J. (1997). The gender gap: Differences in political attitudes and social dominance orientation. British Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 49–68.

Reeves, K. (1997). Voting hopes or fears? White voters, Black candidates & racial politics in America. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Ronquillo, J., Denson, T. F., Lickel, B., Zhong-Lin, L., Nandy, A., & Maddox, K. B. (2007). The effects of skin tone on race-related amygdala activity: An fMRI investigation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 2(1), 39–44.

Schuman, H., Steeh, C., Bobo, L., & Krysan, M. (1997). Racial attitudes in America: Trends and interpretations. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP.

Seltzer, R., & Smith, R. (1991). Color differences in the Afro-Am. Community and the differences they make. Journal of Black Studies, 21(3), 279–286.

Sigelman, C. K., Sigelman, L., Walkosz, B. J., & Nitz, M. (1995). Black candidates, White voters: Understanding racial bias in political perceptions. American Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 243–265.

Sniderman, P. M., & Carmines, E. G. (1997). Reaching beyond race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Strickland, R. A., & Whicker, M. L. (1992). Comparing the wilder and Gantt campaigns: A model for Black candidate success in statewide elections. PS: Political Science and Politics, 25(2), 204–212.

Terkildsen, N. (1993). When white voters evaluate Black candidates: The processing implications of candidate skin color, prejudice, and self-monitoring. American Journal of Political Science, 37(4), 1032–1053.

The National Election Studies (www.umich.edu/~nes). THE 2004 NATIONAL ELECTION STUDY [dataset]. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Center for Political Studies.

Tomz, M., Jason W., & King, G. (2001). Clarify: Software for interpreting and presenting statistical results. Version 2.0 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. http://gking.harvard.edu.

Uhlmann, E., Dasgupta, N., Elgueta, A., Greenwald, A. G., & Swanson, J. (2002). Subgroup prejudice based on skin color among Hispanics in the United States and Latin America. Social Cognition, 20(3), 198–226.

Wade, T. J., Romano, M., & Blue, L. (2004). The effect of African American skin color on hiring preferences. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(12), 2550–2558.

Yinger, J. (1995). Closed doors, opportunities lost: The continuing costs of housing discrimination. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Acknowledgments

Data collection for this experiment was made possible by the Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (NSF Grant 0094964, Diana C. Mutz and Arthur Lupia, principle investigators). I am grateful to the following scholars for giving very useful feedback at various stages of the design of this study: Mahzarin Banaji, Michael Dawson, David Ellwood, Don Green, Jim Glaser, Jennifer Hochschild, Vince Hutchings, Shanto Iyengar, Jeff Jenkins, Taeku Lee, Amy Lerman, Rose McDermott, Tali Mendelberg, Katherine Newman, Mark Peffley, Lynn Sanders, John Sides, and Sid Verba. I thank Ethan Haymovitz for creating the morphed images. Thanks to TESS co-PIs Diana Mutz and Arthur Lupia and Knowledge Networks staff for improving the final protocol prior to fielding and for careful execution of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weaver, V.M. The Electoral Consequences of Skin Color: The “Hidden” Side of Race in Politics. Polit Behav 34, 159–192 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9152-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9152-7