Abstract

Why do men score better than women do on tests of political knowledge? We consider the roots of the gender gap in political knowledge in late adolescence. Using a panel survey of high school seniors, we consider the differences between young men and young women in what they know about politics and how they learn over the course of a midterm election campaign. We find that even after controlling for differences in dispositions like political interest and efficacy, young women are still significantly less politically knowledgeable than young men. While campaigns neither widen nor close the gender gap in political knowledge, we find important gender differences in how young people respond to the campaign environment. While partisan conflict is more likely to promote learning among young men, young women are more likely to gain information in environments marked by consensus rather than conflict.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This survey was made possible with support from the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning & Engagement (CIRCLE) and the University of Colorado’s Innovative Seed Grant Program.

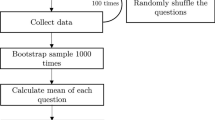

Specifically, pre-election interviews occurred from July 21 to October 8, 2006, and were conducted by Perceptive Market Research. Respondents were drawn from a database of about eight million students, provided by American Student Lists. The response rate for completed interviews in the pre-election survey was 43%. Because the survey window covers a somewhat long period, it is possible that we might see greater knowledge gains from those interviewed early in the panel than those interviewed later. If this is the case, then we could end up underestimating overall levels of campaign learning.

In comparison, 56% of the sample in the 2006 American National Election Study lived in states with a gubernatorial and Senate race, 19% resided in states with only a gubernatorial race, 22% saw only a Senate contest, and 3% lived in a state with no major state level contest.

The states retain sample sizes equivalent to each other in the second wave of the survey. The response rate for completed interviews in the post-election survey was 62%.

The items scale together well, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83. Principal components factor analysis based on polychoric correlations also reveals a single factor solution, with factor loadings ranging between 0.51 and 0.86.

We rely on a traditional survey-based measure of factual political knowledge, which is the best available but could underestimate students’ capabilities to gather political knowledge (Prior and Lupia 2008). This measure could also be seen as a tough test of knowledge for adolescents, who might not be concerned about issues like stem cell research. However, given a sample of young people on the cusp of adulthood, we are interested in how well they perform on a test of knowledge similar to what we would ask of an adult citizen.

We also considered the gender gap across all racial group memberships. In their research, Gimpel et al. (2003) find that the gender gap in knowledge is reversed among their sample of African American high schoolers, with females reporting higher political knowledge than males. In this sample, we find that females are less politically knowledgeable than males among white, Latino, and black subgroups, though this gender gap is greatest among whites and smallest among African Americans.

Female high school seniors are significantly less likely than male students to report the correct answer for each of the components of the political knowledge scale. We do not find, for instance, female students to be better able to identify the partisanship of the female candidate Hillary Clinton.

These items have similar wording to two of the four items that Niemi et al. (1991) argue to be good measures of internal political efficacy.

Except for the descriptive representation measure on state legislative composition, all measures are rescaled 0 to 1, allowing for direct comparison of the coefficients.

This could represent differing responsiveness to the kinds of media resources that these families can better provide, or perhaps indicates that young women benefit particularly from the open (rather than authoritative) climate for political discussion common in families of higher socioeconomic status (Saphir and Chaffee 2002).

As with the pre-election wave, the post-election knowledge items scale together well, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85. Principal components factor analysis based on polychoric correlations reveals a single factor solution, with factor loadings ranging between 0.59 and 0.90.

As shown in Table 1, the political dispositions that predict pre-election political knowledge do not change much over the course of the campaign. This holds among adolescents of both genders, where young men and young women are equally unlikely to report increasing attention to politics from before the election to after. As such, in explaining changes in levels of political learning, we focus on the socializing forces within a student’s context rather than these largely stable dispositions. We control for pre-election knowledge to help capture any differences in political dispositions by gender.

No women were general election candidates in the gubernatorial races in any of the states within this sample.

The effects of Senate campaign intensity are robust in models that exclude the measures of political talk.

Young women are no more likely to talk about politics with their parents than young men are—this holds true for both pre-election rates of talk (t = 0.30, p < 0.38) and post-election rates of discussion with parents (t = −0.31, p < 0.38). Young women are less likely to discuss politics with their friends than young men are, which holds true both before the election (t = 1.84, p < 0.04) and after (t = 2.09, p < 0.02).

This range includes about 85% of the cases in the dataset.

We also find significant differences by gender at the very lowest levels of partisan diversity, specifically when the margin of victory separating the candidates in that county exceeds 72%. However, only about 2% of our overall sample experiences this high of a level of partisan homogeneity.

Or perhaps gender differences could be even more deeply rooted, in genetic tendencies or personality.

References

Atkeson, L. R. (2003). Not all cues are created equal: The conditional impact of female candidates on political engagement. Journal of Politics, 65, 1040–1061.

Atkeson, L. R., & Rapoport, R. B. (2003). The more things change the more they stay the same: Examining gender differences in political attitude expression, 1952–2000. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67, 495–521.

Banwart, M. C. (2007). Gender and young voters in 2004: The influence of perceived knowledge and interest. American Behavioral Scientist, 50, 1152–1168.

Basinger, S. J., & Lavine, H. (2005). Ambivalence, information, and electoral choice. American Political Science Review, 99, 169–184.

Bennett, L. L. M., & Bennett, S. E. (1989). Enduring gender differences in political interest: The impact of socialization and political dispositions. American Politics Research, 17, 105–122.

Bennett, S. E., Flickinger, R. S., & Rhine, S. L. (2000). Political talk over here, over there, over time. British Journal of Political Science, 30, 99–119.

Burns, N., Schlozman, K. L., & Verba, S. (2001). The private roots of public action: Gender, equality, and political participation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Campbell, D. E. (2006). Why we vote: How schools and communities shape our civic life. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Campbell, D. E., & Wolbrecht, C. (2006). See Jane run: Women politicians as role models for adolescents. Journal of Politics, 68(2), 233–247.

Carroll, S. (1994). Women as candidates in American politics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Coleman, J. J., & Manna, P. F. (2000). Congressional campaign spending and the quality of democracy. Journal of Politics, 62, 757–789.

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (2000). Gender and political knowledge. In S. Tolleson-Rinehart & J. J. Josephson (Eds.), Gender and American politics: Women, men, and the political process. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Djupe, P. A., Sokhey, A. E., & Gilbert, C. P. (2007). Present but not accounted for? Gender differences in civic resource acquisition. American Journal of Political Science, 51, 906–920.

Dolan, K. (2006). Symbolic mobilization? The impact of candidate sex in American elections. American Politics Research, 34, 687–704.

Dow, J. K. (2009). Gender differences in political knowledge: Distinguishing characteristics-based and returns-based differences. Political Behavior, 31, 117–136.

Gelman, A., & King, G. (1993). Why are American presidential election campaign polls so variable when votes are so predictable? British Journal of Political Science, 23, 409–451.

Gidengil, E., Giles, J., & Thomas, M. (2008). The gender gap in self-perceived understanding of politics in Canada and the United States. Politics & Gender, 4, 535–561.

Gimpel, J. G., Lay, J., Celeste, S., & Jason, E. (2003). Cultivating democracy: Civic environments and political socialization in America. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Greenstein, F. I. (1969). Children and politics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hooghe, M., & Stolle, D. (2004). Good girls go to the polling booth, bad boys go everywhere: Gender differences in anticipated political participation among American fourteen-year-olds. Women and Politics, 26, 1–23.

Howell, S. E., & Day, C. L. (2000). Complexities of the gender gap. Journal of Politics, 62, 858–872.

Huckfeldt, R. (2001). The social communication of political expertise. American Journal of Political Science, 45(2), 425–438.

Huckfeldt, R., Carmines, E. G., Mondak, J. J., & Zeemering, E. (2007). Information, activation, and electoral competition in the 2002 congressional elections. Journal of Politics, 69(3), 798–812.

Huckfeldt, R., & Sprague, J. (1995). Citizens, politics, and social communication: Information and influence in an election campaign. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jennings, M. K. (1983). Gender roles and inequalities in political participation: Results from an eight-nation study. Western Political Quarterly, 36(3), 364–385.

Jennings, M. K. (1996). Political knowledge over time and across generations. Public Opinion Quarterly, 60, 228–252.

Jennings, M., Kent, N., & Richard, G. (1981). Generations and politics: A panel study of young adults and their parents. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jennings, M. K., & Niemi, R. G. (1974). The political character of adolescence: The influence of families and schools. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kenski, K. (2000). Women and political knowledge during the 2000 primaries. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 572, 26–28.

Kenski, K., & Jamieson, K. H. (2000). The gender gap in political knowledge: Are women less knowledgeable than men about politics? In K. H. Jamieson (Ed.), Everything you think you know about politics…and why you’re wrong. New York: Basic Books.

Koch, J. (1997). Candidate gender and women’s psychological engagement in politics. American Politics Quarterly, 25(1), 118–133.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2006). How voters decide: Information processing during election campaigns. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lawless, J. L. (2004). Politics of presence? Congresswomen and symbolic representation. Political Research Quarterly, 57, 81–99.

Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should blacks represent blacks and women represent women? A contingent “yes”. Journal of Politics, 61(3), 628–657.

McDevitt, M., & Ostrowski, A. (2009). The adolescent unbound: Unintentional influence of curricula on ideological conflict seeking. Political Communication, 26(1), 11–29.

McIntosh, H., Hart, D., & Youniss, J. (2007). The influence of family political discussion on youth civic development: Which parent qualities matter? PS: Political Science & Politics, 40(3), 495–499.

Mendez, J. M., & Osborn, T. (2010). Gender and the perception of knowledge in political discussion. Political Research Quarterly, 63(2), 269–279.

Miller, R., Wilford, R., & Donoghue, F. (1999). Personal dynamics as political participation. Political Research Quarterly, 52(2), 269–292.

Mondak, J. J. (1999). Reconsidering the measurement of political knowledge. Political Analysis, 8, 57–82.

Mondak, J. J., & Anderson, M. R. (2004). The knowledge gap: A reexamination of gender-based differences in political knowledge. Journal of Politics, 66, 492–512.

Niemi, R. G., Craig, S. C., & Mattei, F. (1991). Measuring internal political efficacy in the 1988 National Election Study. American Political Science Review, 85(4), 1407–1413.

Niemi, R. G., & Junn, J. (1998). Civic education: What makes students learn. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Norrander, B. (2008). The history of the gender gaps. In L. D. Whitaker (Ed.), Voting the gender gap. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Norrander, B., & Wilcox, C. (2008). The gender gap in ideology. Political Behavior, 30(4), 503–523.

Pacheco, J. S. (2008). Political socialization in context: The effect of political competition on youth voter turnout. Political Behavior, 30(4), 415–436.

Partin, R. W. (2001). Campaign intensity and voter information: A look at gubernatorial contests. American Politics Research, 29, 114–140.

Popkin, S. L., & Dimock, M. A. (1999). Political knowledge and citizen competence. In S. L. Elkin & S. Karol Edward (Eds.), Citizen competence and democratic institutions. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Prior, M., & Lupia, A. (2008). Money, time, and political knowledge: Distinguishing quick recall and political learning skills. American Journal of Political Science, 52(1), 169–183.

Reingold, B., & Harrell, J. (2010). The impact of descriptive representation on women’s political engagement: Does party matter? Political Research Quarterly, 63(2), 280–294.

Saphir, M. N., & Chaffee, S. H. (2002). Adolescents’ contributions to family communication patterns. Human Communication Research, 28(1), 86–108.

Sapiro, V., & Conover, P. J. (1997). The variable gender basis of electoral politics: Gender and context in the 1992 election. British Journal of Political Science, 27, 497–523.

Sears, D. O., & Valentino, N. A. (1997). Politics matters: Political events as catalysts for preadult socialization. American Political Science Review, 91, 45–65.

Sniderman, P. M., Glaser, J. M., & Griffin, R. (1991). Information and electoral choice. In P. M. Sniderman, R. A. Brody, & P. E. Tetlock (Eds.), Reasoning and choice: Explorations in political psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tedin, K. L. (1980). Assessing peer and parent influence on adolescent political attitudes. American Journal of Political Science, 24(1), 136–154.

Verba, S., Burns, N., & Schlozman, K. L. (1997). Knowing and caring about politics: Gender and political engagement. Journal of Politics, 59(4), 1051–1072.

Walsh, K. C. (2004). Talking about politics: Informal groups and social identity in American life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Question Wordings

Appendix: Question Wordings

Political knowledge (response options: Democrat, Republican, don’t know)

-

“Which party do you consider more liberal?”

-

“Which party would you say is more in favor of raising the minimum wage?”

-

“Which party is more in favor of stem-cell research?”

-

“Which party is more in favor of defining marriage as solely between a man and a woman?”

-

“Which party is more in favor of tax cuts to help stimulate the economy?”

-

“Which party controls the U.S. House of Representatives?”

-

“Which party controls the U.S. Senate?”

-

“What is the party affiliation of Hillary Clinton?”

-

“What is the party affiliation of Al Gore?”

-

“What is the party affiliation of Richard Cheney?”

Interest and attention to politics

-

Political interest (pre-election) “In general, how much interest do you have in politics?” 0—None, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1—A great deal

-

Attention to political news (pre-election) “How much attention do you pay to news about politics? Please use a 1 to 5 scale, with 1 meaning ‘none’ and 5 ‘a great deal.’”

-

Cognitive engagement with political news (pre-election) “When I hear news about politics, I try to figure out what is really going on.” Not like me, Somewhat like me, A lot like me

Efficacy

-

Internal efficacy (pre-election) Average of two items: “I feel confident that I can understand political issues.” and “When it comes to political knowledge, I feel better informed about issues than most people.” Not like me, Somewhat like me, A lot like me

Partisanship

-

Party identification (pre-election) “Which of the following best represents your beliefs in terms of a political party or a political stance? Green Party, Libertarian, Democrat, Republican, some other political stance, or would you say that you are not really political?” 1: Identifies with a party, 0: Does not name a party

-

Strength of partisanship (pre-election) “How strongly do you identify with this political party or political stance? Use a 1-to-10 scale with 1 meaning ‘weak identification’ and 10 meaning ‘strong identification.’” (Coded 0 for those not identifying with a party)

Resources

-

Parental education (pre-election) “Please indicate the highest level of education completed for your mother or father.” (some high school, high school, some college, college, attended graduate school)

-

Parental income (pre-election) “For statistical purposes we need to estimate your parents’ household income before taxes.” (less than $15,000, $15,000–$25,999, $26,000–$40,999, $41,000–$65,000, above $65,000)

-

Civic curricula (pre-election) Sum of three items: “Have you participated in student government?” “Did you participate in any service learning programs?” “Did you ever participate in activities such as mock elections or mock trials?”

Interpersonal political communication

-

Initiates political talk (pre-election) “Sometimes people get caught up in various conversations, but how often do you initiate conversations about politics?” 0—Never, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1—Frequently.

-

Tendency to challenge parents Average of three items: “How often do you express a political opinion to challenge a parent?” “How often do you express an opinion to provoke some response from parents?” “How often do you express an opinion to see if it might upset your parents?” 0—Never, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1—Frequently

-

Conflict avoidance “Discussions about politics sometimes make me feel uncomfortable.” Not like me, Somewhat like me, A lot like me

-

Listens to different views (pre-election) “How often do you listen to people talk about politics when you know that you already disagree with them?” 0—Never, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1—Frequently.

Frequency of political talk

-

Political talk with parents (pre-election and post-election) “How often do you talk about politics with your parents?” 0—Never, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1—Frequently

-

Political talk with friends (pre-election and post-election) “How often do you talk about politics with friends?” 0—Never, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1—Frequently

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wolak, J., McDevitt, M. The Roots of the Gender Gap in Political Knowledge in Adolescence. Polit Behav 33, 505–533 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9142-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-010-9142-9