Abstract

Fertilizer N availability impacts photosynthesis and crop performance, although cause–effect relationships are not well established, especially for field-grown plants. Our objective was to determine the relationship between N supply and photosynthetic capacity estimated by leaf area index (LAI) and single leaf photosynthesis using genetically diverse field-grown maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids. We compared a high yield potential commercial hybrid (FR1064 x LH185) and an experimental hybrid (FR1064 x IHP) with low yield potential but exceptionally high grain protein concentration. Plant biomass and physiological traits were measured at tassel emergence (VT) and at the grain milk stage (R3) to assess the effects of N supply on photosynthetic source capacity and N uptake, and grain yield and grain N were measured at maturity. Grain yield of FR1064 x LH185 was much greater than FR1064 x IHP even though plant biomass and LAI were larger for FR1064 x IHP, and single leaf photosynthesis was similar for both hybrids. Although photosynthetic capacity was not related to hybrid differences in productivity, increasing N supply led to proportional increases in grain yield, plant biomass, LAI, photosynthesis, and Rubisco and PEP carboxylase activities for both hybrids. Thus, a positive relationship between photosynthetic capacity and yield was revealed by hybrid response to N supply, and the relationship was similar for hybrids with a marked difference in yield potential. For both hybrids the N response of single leaf CER and initial Rubisco activity was negative when expressed per unit of leaf N. In contrast, PEP carboxylase activity per unit leaf N increased in response to N availability, indicating that PEP carboxylase served as a reservoir for excess N accumulation in field-grown maize leaves. The correlation between CER and initial Rubisco activity was highly significant when expressed on a leaf area or a total leaf basis. The results suggest that regardless of genotypic yield potential, maize CER, and potentially grain yield, could be improved by increasing the partitioning of N into Rubisco.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Crop productivity results from the integration of multiple environmental and genetic processes throughout the life of the crop that differ in intensity and timing of action. To achieve high yield plants must establish optimal photosynthetic capacity and then maintain a high rate of photosynthesis during the grain filling period. N supply plays a major role in both processes by maximizing LAI and the biochemical components of the photosynthetic apparatus (Below et al. 2000; Below 2002).

A positive response of photosynthetic rate to leaf N concentration has been widely reported (Muchow and Sinclair 1994; Sinclair and Muchow 1995; Paponov and Engels 2003). Much of the N allocated to the photosynthetic apparatus of C4 plants such as maize is invested into biosynthesis of Rubisco, PEP carboxylase, and pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase (PPDK). Similar to C3 plants, the ultimate limitation to CO2 fixation in C4 plants is the activity of Rubisco (von Caemmerer et al. 1997; Edwards et al. 2001). However, alterations in N allocation to other components of the photosynthetic apparatus, such as the C4 enzymes, could indirectly impact the fixation of CO2 via Rubisco.

The supply of N has been shown to differentially impact the biosynthesis and accumulation of photosynthetic enzymes in young maize plants grown in hydroponic culture (Sugiyama et al. 1984; Sugiharto et al. 1990; Sugiharto and Sugiyama 1992; Suzuki et al. 1994). In particular, PEP carboxylase is especially responsive to recovery from N deficiency, with protein content increasing to a greater extent compared to Rubisco or PPDK. In contrast, in Amaranthus cruentus leaves, Rubisco and not PEP carboxylase or PPDK, was the photosynthetic enzyme most responsive to changes in N supply (Tazoe et al. 2006).

While high grain yield is clearly a function of photosynthetic capacity, yield is also dependent on environmental and genetic factors associated with the ability of the kernel sink to accumulate assimilates. Considerable genetic variability exists among maize hybrids for traits associated with the kernel’s ability to utilize assimilates, and many studies have used diverse genetic materials to assess C and N interactions impacting growth and development of the grain (Rizzi et al. 1996; Below et al. 2004; Uribelarrea et al. 2004, 2007; Wyss et al. 1991). Materials derived from the Illinois Protein Strains have been particularly useful in this context, and Illinois High Protein (IHP) (and its resulting hybrids) is particularly responsive to N supply in terms of plant N accumulation. The high kernel protein concentration of IHP, however, has been achieved primarily by decreasing kernel starch accumulation resulting in decreased kernel size and yield compared to conventional hybrids (Lohaus et al. 1998; Uribelarrea et al. 2004, Uribelarrea et al. 2007).

In this field experiment we determined the relationships between photosynthetic traits and N supply using maize hybrids with well-characterized differences in yield potential due to divergent sink capacity for N and C accumulation. We show that allocation of N to photosynthetic components and yield in response to N supply were remarkably similar for hybrids that differed greatly in kernel traits associated with yield and protein metabolism.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growing conditions

Field experiments were conducted at the Department of Crop Sciences Research and Education Center in Champaign, Illinois during the 2005 growing season, on plots that had previously been shown to be responsive to N fertilizer (Uribelarrea et al. 2004). Briefly, the soil was a Drummer silty clay loam with an average organic matter of 4.7% and a pH of 6.2. Plots were kept weed-free with both herbicides and hand cultivation, and the crop was irrigated when necessary. A standard commercial hybrid (FR1064 x LH185), and an experimental high protein hybrid (FR1064 x IHP), known to exhibit different N use and productivity characteristics (Uribelarrea et al. 2004, 2007) where grown under four levels of fertilizer N supply ranging from deficient to more than adequate (0, 56, 112, and 224 kg N ha−1). Hybrids were over seeded on 29 April 2005, and thinned to achieve a stand density of 70,000 plants ha−1. The fertilizer was hand applied in a diffuse band down the center of the row as ammonium sulfate and incorporated when the crop was between the V2 and V3 growth stages (Ritchie et al. 1997). Treatments consisted of a factorial combination of the two hybrids and four fertilizer rates and where arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications. Each experimental unit consisted of 4-row plots that were 5.3 m long by 3 m wide, and the two central rows were used for final yield determination and destructive plant samplings.

Crop measurements

Biomass and N accumulation

To assess biomass and N accumulation, whole shoots (all above-ground portions) were sampled at tassel emergence (VT), and physiological maturity (R6), when 50% of the plants exhibited a visible black layer at the base of the kernel. By R6, maize plants are considered to have attained their maximum biomass (Ritchie et al. 1997).

At each sampling time, four plants visually selected to represent the plot average, were cut at the soil surface and separated into stover (vegetative fraction), and grain fractions (only at R6 sampling). Grain fractions were placed into a forced-draft oven (75°C), while the fresh weight of the entire vegetative plant fraction was determined prior to shredding. An aliquot of the shredded material was weighed fresh and then oven-dried (75°C) to constant weight. The dry weight of the vegetative fraction was calculated using the fresh weight and the moisture level. All individual vegetative plant samples were ground in a Wiley mill to pass a 20 mesh screen, and analyzed for total N concentration [g kg−1] using a combustion technique (NA2000 N-Protein, Fisons Instruments). The total shoot N content [g N plant−1] was calculated by multiplying the dry weight by the N concentration and adding grain N content. Grain N content was calculated as the product of the grain dry weight by grain N concentration (determined by near infra-red reflectance, DickeyJohn Instalab-6000).

Gas exchange and biochemical measurements

Gas exchange, enzyme activities and enzyme abundances were determined for the 0, 56, and 224 kg N ha−1 N treatments. Steady state carbon dioxide exchange rate was measured with the Li-Cor 6400 (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE) using a light intensity of 1,900 μmol m−2 s−1 PAR, a constant 380 μmol mol−1 partial pressure of CO2 in the sample chamber, and ambient temperature. Measurements were taken between 10:00 and 14:00 h at tassel emergence (VT) and at the grain milk stage (R3). Individual leaf area was determined using the formula of McKee (1964) and Dwyer and Stewart (1986) as length x maximum width x 0.73.

Leaf discs (1.09 cm2) from the same section of the leaf used for CER were removed and immediately frozen in liquid N2 after removing the leaf chamber. Samples were stored at −80°C for subsequent enzyme assay and Western blot analysis. A separate set of leaf discs was oven dried (75°C) to constant weight and specific leaf weight [mg cm−2], N concentration (NA2000 N-Protein, Fisons Instruments) [g kg−1], and specific leaf N [mg N cm−2] were determined.

For the activity of PEP carboxylase, leaf discs were extracted in ice-cold 100 mM HEPES, pH7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1% (w/v) casein, 1% (w/v) PVP, 14 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100. PEP carboxylase was assayed spectrophotometrically at 30°C as described by Crafts-Brandner and Salvucci (2002). Assays were conducted at pH 8.0 under optimal conditions to provide an estimate of the maximum potential enzyme activity. Leaf tissue was also assayed for initial Rubisco activity as described in detail by Crafts-Brandner and Salvucci (2000). Rubisco activity was determined by incorporation of 14CO2 into acid-stable products at 30°C (Salvucci 1992), and each extract was assayed in duplicate.

For quantification of PEP carboxylase and Rubisco, leaf discs were homogenized in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH7.5, and 0.1% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, and aliquots were then mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiled for 3 min as described by Feller et al. (1998). Samples representing equal amounts of leaf area were electrophoresed in 10% (w/v) SDS-PAGE gels according to the method of Chua (1980). Polypeptides were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose and were probed with a monospecific polyclonal antibody against maize PEP carboxylase on the N-terminal 25 amino acids of the Rubisco large subunit (provided by R. Houtz, University of Kentucky and M. Mulligan, University of California, Irving). Resulting blots were scanned using a Chemi Imager Ready reflective Scanner (Alpha Innotech Corp.) and analyzed using Alpha Ease (v 5.5) software.

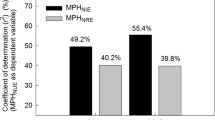

Statistical analysis

For each variable, the effects of fertilizer N rate and hybrid (and their interaction) were analyzed with the MIXED procedure in SAS (SAS Inst. 2000). All variables were checked for normality and in no instance there was need for data transformation. The hybrid and N rate factors were considered fixed, and replications as random factors. Means separation was done by using the PDIFF option within the MIXED procedure for biomass data in Table 2, and leaf data in Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5. Regression parameters in Fig. 1 were also fitted using the MIXED procedure considering N rate as a continuous variable. Only those effects which were significant at α = 0.05 are included and discussed in the results. Least square means for fixed effects were separated using appropriate standard errors at α = 0.05. Western blots were scanned and the values shown in Fig. 6 correspond to Integrated Density Values (IDV) averaged across the four scanned replications. However, only a single representative gel replicate is presented in Fig. 6.

Results

The significance level for all studied variables are shown in Table 1. Variation due to hybrid and/or N rate was observed for all parameters except specific leaf weight, while hybrid x N rate interactions were observed for shoot N content, grain N concentration, leaf area, and Rubisco activity expressed on a leaf area basis. Except for PEPc activity (leaf area basis), all parameters measurable over time exhibited significant changes due to growth stage (Table 1).

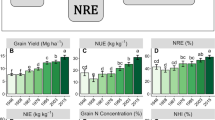

The hybrids differed with regard to yield components in a manner consistent with numerous reports on the Illinois High Protein strains (Rizzi et al. 1996; Below et al. 2004; Uribelarrea et al. 2004; Uribelarrea et al. 2007; Wyss et al. 1991). Nitrogen supply increased grain yield of both hybrids, with the commercial hybrid having a considerably higher yield due to increased kernel size and, to a lesser extent, greater kernel number (Fig. 1a,c,d). Compared to FR1064 x LH185, kernel number of FR1064 x IHP was much more responsive to N supply, especially with the first increment in N supply. Consistent with long-term selection pressure for grain protein in IHP, grain N concentration was significantly higher for FR1064 x IHP compared to FR1064 x LH185 at all N levels (Fig. 1b). However, due to compensatory responses in kernel size and number, the content of grain N per plant was only slightly higher for FR1064 x IHP compared to FR1064 x LH185 (1.76 and 1.65 g N plant−1, respectively).

At the VT growth stage the shoot biomass and LAI were higher for FR1064 x IHP compared to FR1064 x LH185 at all N levels (Table 2). For both hybrids, shoot biomass and LAI were moderately increased with N supply (Table 2), with almost all of the difference in LAI occurring in the leaves nearest the ear (data not shown). Plant height was the same for both hybrids and was unaffected by N. For both hybrids shoot N accumulation increased over the entire range of N fertilizer treatments (Table 2). The response of shoot N accumulation to N supply was much greater for FR1064 x IHP compared to FR1064 x LH185. Treatment effects measured at the VT growth stage were similar to those measured at the R3 growth stage (data not shown).

We selected the leaf above the ear for detailed analysis of growth parameters and photosynthesis because this leaf is generally representative of the whole canopy in terms of leaf area (r = 0.99, p < 0.001; Dwyer and Stewart 1986), and because it is active in supplying the ear with photoassimilates. The area of the leaf above the ear was greater for FR1064 x IHP compared to FR1064 x LH185 at N levels above 0 kg ha−1 (Fig. 2a). Specific leaf weight (mg cm−2) was not affected by N supply or by hybrid, although it did exhibit a marked increase (from 4.5 to 5.7 mg cm−2) between VT and R3 (Fig. 2b). Conversely, leaf N content (mg N leaf−1) increased with N supply (Fig. 2c). In general, the N response of leaf area and leaf N content was greater for FR1064 x IHP compared to FR1064 x LH185.

The CER and activities of PEP carboxylase and Rubisco expressed per unit leaf area were similar for both hybrids (Fig. 3). For both hybrids, the CER per unit leaf area increased with N supply and this was associated with increased PEP carboxylase and initial Rubisco activity. Closer inspection of the data, however, revealed that the relative increase in PEP carboxylase activity in response to N supply was much greater than that of CER and initial Rubisco activity. It was noteworthy that the measured values for initial Rubisco activity were quite similar to those of CER and the correlation coefficient for the two traits was 0.86 (p ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Effect of N fertilizer rate on the net photosynthetic rate (CER) (a), the activity of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPc) (b) and the Rubisco initial activity (c) per leaf area for the leaf above the ear for two maize hybrids grown in Champaign, IL in 2005. Measurements where taken at the VT and R3 growth stages. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean

Relationship between Rubisco initial activity and net photosynthesis measured on the leaf above the ear of two maize hybrids grown at varying N fertilizer rates in Champaign, IL in 2005. CER and Rubisco initial activity were measured on the same leaf for each treatment at the VT and R3 growth stages. Data are expressed as a rate per unit leaf area per second for treatment means. Vertical and horizontal bars represent the standard error of each mean. White and black symbols correspond to the high protein and the commercial hybrids correspondingly. Circles, triangles and squares represent values for plants grown at 0, 56, or 224 kg N ha−1

The differential N response of PEP carboxylase compared to CER and initial Rubisco activity was more clearly revealed when data were expressed per unit of leaf N (Fig. 5). Between VT and R3 there was a much larger relative decrease in CER and initial Rubisco activity compared to PEP carboxylase activity. Additionally, whereas CER and initial Rubisco activity declined or stayed constant with increasing N availability, there was a pronounced increase in PEP carboxylase activity in response to N treatment. This differential N response of PEP carboxylase and Rubisco activity was supported by Western blot analysis of enzyme abundance (Fig. 6). For both hybrids there was a more pronounced increase in abundance of PEP carboxylase (48% average increase) compared to Rubisco large subunit (29% increase) as N supply was increased from 0 to 224 kg ha−1.

Effect of N fertilizer rate on the net photosynthetic rate (CER) (a), the activity of PEP carboxylase (PEPc) (b) and the Rubisco initial activity (c), expressed per unit of leaf N, for two maize hybrids grown in Champaign, IL in 2005. Measurements where taken at the VT and R3 growth stages, on the leaf above the ear. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean

Western blots indicating the abundance of PEP carboxylase (PEPc) and the Rubisco large subunit extracted from 1.09 cm2 of leaf area sampled at the R3 growth stage from the leaf above the ear of two maize hybrids grown at 0, 56, or 224 kg N ha−1 in Champaign, IL in 2005. Numbers on top of each band indicate integrated density values

Discussion

Consistent with previous research with IHP hybrids (Uribelarrea et al. 2004, 2007), vegetative plant development and partitioning of dry matter and N to the kernels differed from that of the commercial hybrid. In particular, FR1064 x IHP had a significantly higher LAI at all N levels compared to FR1064 x LH185, although this apparent advantage in photosynthetic capacity was not associated with higher grain yield. This finding could be explained by kernel-specific traits associated with assimilate requirements for kernel initiation and development. On a per plant basis the kernel N content was only slightly higher for FR1064 x IHP compared to FR1064 x LH185. However, the high kernel N concentration (gN kg−1) of the IHP hybrid was associated with decreased kernel starch accumulation (data not shown, Uribelarrea et al. 2004) and decreased kernel number. This decrease in kernel starch accumulation led to lower individual kernel weight and lower grain yield.

Although the hybrids differed greatly with regard to LAI and kernel N and C accumulation at a given level of N supply, the relative N response of the hybrids for grain yield or traits associated with photosynthetic metabolism was remarkably similar for both hybrids. We focused on traits associated with photosynthetic N use efficiency. Photosynthetic N use efficiency is determined in large part by specific leaf weight (SLW) and by the allocation of leaf N to photosynthetic enzymes (Poorter and Evans 1998; Evans and Poorter 2001). Specific leaf weight was constant across N treatments (Fig. 2b), whereas leaf N accumulation increased with N supply (Fig. 2c), indicating that investment in photosynthetic machinery per unit leaf area increased with N supply. As reported previously (Evans 1993; Ding et al. 2005), single leaf CER was not predictive of the yield difference measured between hybrids at any of the N levels. Measurements of CER were made on well-watered plants under saturating PAR, at optimal temperature, and well before the onset of monocarpic senescence. Considering these factors, and the observation that hybrid variation in kernel growth can be independent of assimilate supply (Jones and Simmons 1983; Borrás and Otegui 2001), it is not surprising that single leaf CER was not indicative of hybrid yield variation.

Single leaf CER was, however, associated with the N response of shoot biomass accumulation and LAI at the VT and R3 growth stages, and with the N response of grain yield. Furthermore, there was a striking relationship between CER and initial Rubisco activity measured on the same leaf. Under our sampling conditions that promoted full activation of Rubisco, its activity was numerically similar to the rate of CER when expressed on a leaf area or on a total leaf basis. There was a close relationship (r2 = 0.76, p ≤ 0.05) between CER and Rubisco initial activity measured in leaf samples from all combinations of N treatments, hybrids and growth stages. These results indicate that CER is regulated by the activity of Rubisco for leaves that vary significantly in N status, potentially through the activation status of Rubisco, a process that is regulated by Rubisco activase (Law and Crafts-Brandner 1999). We propose that there may be a close relationship between the critical level of fertilizer N required for optimal yield and the partitioning of N into Rubisco in maize leaves.

Previous studies have shown that PEP carboxylase synthesis/activity in leaves of N-starved maize seedlings responds to N supply to a greater degree than Rubisco or pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase (Sugiyama et al. 1984; Sugiharto et al. 1990; Sugiharto and Sugiyama 1992; Suzuki et al. 1994). These studies, however, were all conducted under controlled conditions in hydroponics in the greenhouse, and our results confirm and extend these reports for mature maize plants grown in a typical field setting. PEP carboxylase activity measured under conditions to indicate maximum enzyme potential was similar for both hybrids at both sampling times, and the activity increased for both hybrids with N supply. The relative increase in PEP carboxylase activity with increasing N supply, however, greatly exceeded that of CER and Rubisco initial activity. This differential response to N became quite apparent by expressing the activity per unit of leaf N (Fig. 5). Net photosynthesis and Rubisco activity per mg leaf N declined or stayed constant as the N supply increased, whereas PEP carboxylase activity increased progressively with N supply. Western blot analysis of Rubisco and PEP carboxylase abundances (Fig. 6) supported the enzyme activity data. Apparently there is a threshold level of leaf N for maximum partitioning into Rubisco. Leaf N accumulated in excess of this threshold did not increase Rubisco abundance, but continued to be partitioned into PEP carboxylase. Experiments by Mae al. (1983) indicated that Rubisco synthesis in rice (Oryza sativa L.) leaves occurs predominantly between emergence and full leaf expansion with little synthesis occurring after full leaf expansion. More recently, Imai et al. (2005) showed that the decline of Rubisco synthesis after full leaf expansion was closely associated with a decline in leaf N influx rather than decreased abundance of rbcS and rbcL mRNA’s. Thus, we hypothesize that the additional leaf N accumulating in maize leaves with increased N supply was preferentially partitioned to cells other than bundle sheath cells where Rubisco is synthesized.

Our results using field-grown maize support earlier reports using seedling plants, indicating that N partitioning into PEP carboxylase, but not Rubisco, continues at N levels that exceed the optimum for maximum growth (Sugiyama et al. 1984; Makino et al. 2003). The partitioning of N into PEP carboxylase did not provide a benefit to CER suggesting that this enzyme may function as a storage reservoir for excess leaf N. Interestingly, Tazoe et al. (2006) found that leaf N was preferentially partitioned in Rubisco rather than PEP carboxylase in the C4 dicot Amaranthus cruentus. Thus, the response to N of components in the photosynthetic apparatus of C4 plants may vary with the biochemical subtype (i.e. NADP-malic enzyme versus NAD-malic enzyme subtypes).

Conclusions

We analyzed the impact of N supply on the photosynthetic N use efficiency of maize hybrids with marked differences in yield potential and grain protein concentration. Despite the large genotypic differences in kernel traits, the relative response to increasing N supply for all other traits measured was similar for both hybrids. Single leaf CER, while not indicative of hybrid yield differences, was closely associated with the N response of shoot biomass at the VT and R3 growth stages, and with LAI and grain yield. Rubisco activity was highly correlated with CER over all N treatment:hybrid combinations, indicating that Rubisco activity regulated CER of leaves that varied widely in N content and in their abundance of Rubisco. In contrast, the N response of PEP carboxylase activity and abundance was much more robust compared to CER and Rubisco. The increased activity and abundance of PEP carboxylase at high N supply did not provide a benefit to CER, suggesting that PEP carboxylase may function as a vegetative storage protein at supra-optimal levels of leaf N. Because the activity of Rubisco regulated CER across all treatments, we hypothesize that Rubisco abundance and activity, and as a result CER, could be limited in maize leaves by processes that regulate the partitioning of leaf N to Rubisco synthesis.

References

Below FE (2002) Nitrogen metabolism and crop productivity. In: Pessarakli M (ed) Handbook of plant and crop physiology. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, Basel, pp 275–301

Below FE, Cazetta JO, Seebauer JR (2000) Carbon/nitrogen interactions during ear and kernel development of maize. In: CSSA Special Publication. Crop Science Society of America, Madison

Below FE, Seebauer JR, Uribelarrea M, Schneerman MC, Moose SP (2004) Physiological changes accompanying long-term selection for grain protein in maize. In: Janick J (ed) Plant Breeding Reviews. Wiley, New Jersey, pp 133–151

Borrás L, Otegui ME (2001) Maize kernel weight response to postflowering source-sink ratio. Crop Sci 41:1816–1822

Chua N-M (1980) Electrophoretic analysis of chloroplast proteins. Methods Enzymol 69:434–446 doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(80)69042-9

Crafts-Brandner SJ, Salvucci ME (2000) Rubisco activase constrains the photosynthetic potential of leaves at high temperature and CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:13430–13435 doi:10.1073/pnas.230451497

Crafts-Brandner SJ, Salvucci ME (2002) Sensitivity of photosynthesis in a C4 plant, maize, to heat stress. Plant Physiol 129:1773–1780 doi:10.1104/pp.002170

Ding L, Wang KJ, Jiang GM, Liu MZ, Niu SL, Gao LM (2005) Post-anthesis changes in photosynthetic traits of maize hybrids released in different years. Field Crops Res 93:108–115

Dwyer LM, Stewart DW (1986) Leaf area development in field-grown maize. Agron J 78:334–343

Edwards GE, Furbank RT, Hatch MD, Osmond CB (2001) What does it take to be C4? Lessons from the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 125:46–49 doi:10.1104/pp.125.1.46

Evans LT (1993) Leaf photosynthesis. In: Crop Evolution, Adaption and Yield. Cambridge University Press. pp.185–218.

Evans JR, Poorter H (2001) Photosynthetic acclimation of plants to growth irradiance: the relative importance of specific leaf area and nitrogen partitioning in maximizing carbon gain. Plant Cell Environ 25:755–767 doi:10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00724.x

Feller U, Crafts-Brandner SJ, Salvucci ME (1998) Moderately high temperature inhibit ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) activase-mediated activation of Rubisco. Plant Physiol 116:539–546 doi:10.1104/pp.116.2.539

Imai K, Suzuki Y, Makino A, Mae T (2005) Effects of nitrogen nutrition on the relationships between the levels of rbcS and rbcL mRNAs and the amount of ribulose 1·5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase synthesized in the eighth leaves of rice from emergence through senescence. Plant Cell Environ 28:1589–1600 doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01438.x

Jones RJ, Simmons SR (1983) Effect of altered source-sink ratio on growth of maize kernels. Crop Sci 23:129–134

Law RD, Crafts-Brandner SJ (1999) Inhibition and acclimation of photosynthesis to heat stress is closely correlated with activation of ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. Plant Physiol 120:173–181 doi:10.1104/pp.120.1.173

Lohaus G, Büker M, Hubmann M, Soave C, Heldt H-W (1998) Transport of amino acids with special emphasis on the synthesis and transport of asparagine in the Illinois Low Protein and Illinois High Protein strains of maize. Planta 205:181–188 doi:10.1007/s004250050310

Mae T, Makino A, Ohira K (1983) Changes in the amounts of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase synthesized and degraded during the life span of rice leaf (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Physiol 24:1079–1086

Makino A, Sakuma H, Sudo E, Mae T (2003) Differences between maize and rice in N-use efficiency for photosynthesis and protein allocation. Plant Cell Physiol 44:952–956 doi:10.1093/pcp/pcg113

McKee GW (1964) A coefficient for computing leaf area in hybrid corn. Agron J 56:240–241

Muchow RC, Sinclair TR (1994) Nitrogen response of leaf photosynthesis and canopy radiation use efficiency in field-grown maize and sorghum. Crop Sci 34:721–727

Paponov IA, Engels C (2003) Effect of nitrogen supply on leaf traits related to photosynthesis during grain filling in two maize genotypes with different N efficiency. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 166:756–763 doi:10.1002/jpln.200320339

Poorter H, Evans JR (1998) Photosynthetic nitrogen-use efficiency of species that differ inherently in specific leaf area. Oecologia 116:26–37 doi:10.1007/s004420050560

Ritchie SW, Hanway JJ, Benson GO (1997) How a corn plant develops. In: Special Report N°48, pp. 20. Iowa State University of Science and Technology Cooperative Extension Service, Ames.

Rizzi E, Balconi C, Bosio D, Nembrini L, Morselli A, Motto M (1996) Accumulation and partitioning of nitrogen among plant parts in the high and low protein strains of maize. Maydica 41:325–332

Salvucci ME (1992) Subunit interactions of rubisco activase: polyethylene glycol promotes self-association, stimulates ATPase and activation activities, and enhances interactions with Rubisco. Arch Biochem Biophys 298:688–696 doi:10.1016/0003-9861(92)90467-B

SAS Institute (2000) SAS user's guide. SAS Inst., Cary

Sinclair TR, Muchow RC (1995) Effect of nitrogen supply on maize yield. I. Modeling physiological responses. Agron J 87:632–641

Sugiharto B, Miyata K, Nakamoto H, Sasakawa H, Sugiyama T (1990) Regulation of expression of carbon-assimilating enzymes by nitrogen in maize leaf. Plant Physiol 92:963–969

Sugiharto B, Sugiyama T (1992) Effects of nitrate and ammonium on gene expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase and nitrogen metabolism in maize leaf during recovery from nitrogen stress. Plant Physiol 98:1403–1408

Sugiyama T, Mizuno M, Hayashi M (1984) Partitioning of nitrogen among ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, and pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase as related to biomass productivity in maize seedlings. Plant Physiol 75:665–669

Suzuki I, Crétin C, Omata T, Sugiyama T (1994) Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of nitrogen-responding expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase gene in maize. Plant Physiol 105:1223–1229

Tazoe Y, Noguchi K, Terashima I (2006) Effects of growth Light and nitrogen nutrition on the organization of the photosynthetic apparatus in leaves of a C4 plant, Amaranthus cruentus. Plant Cell Environ 29:691–700 doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01453.x

Uribelarrea M, Below FE, Moose SP (2004) Grain composition and productivity of maize hybrids derived from the Illinois protein strains in response to variable nitrogen supply. Crop Sci 44:1593–1600

Uribelarrea M, Moose SP, Below FE (2007) Divergent selection for grain protein affects nitrogen use efficiency in maize hybrids. Field Crops Res 100:82–90 doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2006.05.008

von Caemmerer S, Millgate A, Farquhar GD, Furbank RT (1997) Reduction of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase by antisense RNA in the C4 plant Flaveria bidentis leads to reduced assimilation rates and increased carbon isotope discrimination. Plant Physiol 113:469–477

Wyss CS, Czyzewicz JR, Below FE (1991) Source-sink control of grain composition in maize strains divergently selected for protein-concentration. Crop Sci 31:761–766

Acknowledgments

This study is part of project 15-0390 of Agric. Exp. Stn., College of Agricultural, Consumer, and Environmental Sciences, Univ. of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The authors express their gratitude to Ignacio Dellepiane and Mark Harrison for technical assistance, and to Dr. Steven Moose for supplying the seed of FR1064 x IHP and to Dr. Archie Portis for providing the setup to determine the activity of Rubisco.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Len Wade.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Uribelarrea, M., Crafts-Brandner, S.J. & Below, F.E. Physiological N response of field-grown maize hybrids (Zea mays L.) with divergent yield potential and grain protein concentration. Plant Soil 316, 151–160 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-008-9767-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-008-9767-1