Abstract

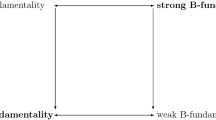

Some see concrete foundationalism as providing the central task for sparse ontology, that of identifying which concreta ground other concreta but aren’t themselves grounded by concreta. There is, however, potentially much more to sparse ontology. The thesis of abstract foundationalism, if true, provides an additional task: identifying which abstracta ground other abstracta but aren’t themselves grounded by abstracta. We focus on two abstract foundationalist theses—abstract atomism and abstract monism—that correspond to the concrete foundationalist theses of priority atomism and priority monism. We show that a consequence of an attractive package of views is that abstract reality has a particular mereological structure, one capable of underwriting both theses. We argue that, of abstract foundationalist theses formulated in mereological terms, abstract atomism is the most plausible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Fine (2012) claims that the notion of grounding is best regimented with a sentential connective, while Audi (2012) and Rosen (2010) instead go with a predicate understood as expressing a relation between facts. While we work with neither of these approaches in what follows, our discussion could be recast in such a way that it embraces either the sentential connective or the fact relation view. What’s important for us (as will become clear later) is that grounding isn’t a relation between entities of various ontological categories. Thanks to an anonymous referee for helpful discussion here.

For a general discussion of grounding that touches on these assumptions and related issues, see Trogdon (2013).

See Wang (2016) for discussion of further category-relative conceptions of fundamentality, conceptions that target objects, properties, relations, and states of affairs. Many claim that fundamental entities are modally free in that they are freely recombinable in some sense. Provided that some abstracta both exist necessarily and have all their intrinsic properties essentially, it’s unlikely that modal freedom is a useful diagnostic for a-fundamentality among abstracta.

Compare Goodman and Quine on nominalism, who claim that the thesis is “based on a philosophical intuition that cannot be justified by an appeal to anything more ultimate” (1947, 174).

Schaffer (2010a) does sketch an argument for foundationalism according to which any grounded entity is grounded by fundamental entities. While Schaffer doesn’t defend any particular foundationalist thesis (he instead defends a particular concrete foundationalist thesis), if foundationalism is true, then perhaps the ultimate task of sparse ontology is to establish which foundationalist thesis is the most plausible. See Trogdon (forthcoming) for critical discussion of Schaffer’s argument.

Just how existence and content grounding are related is an interesting question. Following Sider (2012, Ch. 8), perhaps any proposition that isn’t content grounded is such that its non-propositional constituents aren’t existence grounded. A natural thought is that thus-and-so is existence grounded just in case the proposition that thus-and-so exists is content grounded.

See Oppenheim and Putnam’s (1958) for a seminal articulation and defense of this picture. For more recent discussions, see Kim (1998, Ch. 1, 2002), Schaffer (2003), and Rueger and McGivern (2010). For an alternative approach, see Giberman (2015a) who characterizes the c-fundamental concreta in topological terms.

We assume that any complex concrete entity only has further concreta as proper parts, and any complex abstract entity only has further abstracta as proper parts.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for helpful discussion here.

On competing Platonist options, see Cowling (2017: 92–102, 177–187).

So, we deny that musical works, fictional entities, and directions are among the abstracta, provided that these types of entities are understood non-set-theoretically.

As we explain below, Lewis (1991) argues that set construction is to be analyzed in terms of composition and singleton formation. (His views on singleton formation are complex and we don’t have the space to engage with them here—see Lewis (1993) for further discussion.) There are other approaches to set construction, however. Fine’s (2010) approach, for example, is to take set construction as conceptually primitive. If it turns out that there isn’t a tight link between set construction and mereology, we should probably abandon the compositional approach to abstract foundationalism given a set-theoretic conception of abstracta.

Here and in what follows we use slightly different terminology than Lewis (e.g. he focuses on classes rather than sets, and he classifies the empty set as an individual while we do not).

It doesn’t follow from Lewis’ package of views that the empty set is simple—Lewis in fact suggests that the empty set is the cosmos! We agree that the empty set doesn’t have abstracta as proper parts, but we take the empty set to itself be abstract rather than concrete.

We take the possibility of concrete gunky objects seriously as well as “onion worlds”—roughly, worlds exhibiting infinitely descending qualitative complexity. Note, however, that the former requires no commitment to gunky properties, and, as Williams (2007) argues, neither does the latter.

Compare: a structure of concreta is junky just in case it’s an infinite collection of concreta each of which is a proper part of another. If there are junky structures of concreta then there is no fusion of all concreta, provided that any fusion of concreta is itself concrete. See Bohn (2009) for an argument that it’s possible that the concreta form a junky structure, and Giberman (2015b) for discussion of the idea that there are proper sub-collections of the concreta that form such structures.

According to Lewis, while mixed fusions are “forced upon us” by universalism (the thesis that composition is unrestricted), there is no principle that is both independently plausible and has the result that mixed fusions have singletons (1991, 8). The corresponding principle of unrestricted set-formation, for example, is false, as there is no set of all non-self-membered sets.

See Rosen (2015) for further discussion of the idea that mixed fusions in Lewis’ framework lack properties.

There is another reason to work with a view according to which grounding isn’t a relation in this context: in this case we don’t face the difficult question of what abstracta if any ground the grounding relation itself. It’s true that there is still the question of what makes it the case that particular abstracta ground other abstracta, but notice that this concerns content a-grounding rather than existence a-grounding. As we noted earlier, abstract foundationalist theses target the latter rather than the former.

Indeed, Schaffer (2010b) proposes to analyze the concepts of an integrated whole and a mere aggregate in terms of their grounding profiles—here the idea is that something is an integrated whole just in case it has proper parts and grounds them, and something is a mere aggregate just in case it has proper parts and is grounded by them.

See Craver (2007, Ch. 4) for relevant discussion.

If composition is “ontologically innocent” in Lewis’ (1991, Ch. 3) sense, then mixed fusions don’t ground the things that compose them. But with Lewis’ principle no fusion whatsoever grounds the things that compose it, and this begs the question against the abstract monist (as well as the priority monist).

References

Audi, P. (2012). Grounding: Toward a theory of the in-virtue-of relation. Journal of Philosophy, 109, 685–711.

Benacerraf, P. (1965). What numbers could not be. Philosophical Review, 74, 47–73.

Bliss, R. (2013). Viciousness and the structure of reality. Philosophical Studies, 166, 399–418.

Bohn, E. (2009). Must there be a top level? Philosophical Quarterly, 59, 193–201.

Burgess, J., & Rosen, R. (1997). A subject with no object: strategies for nominalistic interpretation of mathematics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cameron, R. (2008). Turtles all the way down: Regress, priority and fundamentality. Philosophical Quarterly, 58, 1–14.

Cowling, S. (2013). Ideological parsimony. Synthese, 190, 889–908.

Cowling, S. (2017). Abstract entities. London: Routledge.

Craver, C. (2007). Explaining the brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dixon, S. Forthcoming. Upward grounding. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research.

Donaldson, T. (2017). The (metaphysical) foundations of arithmetic? Noûs, 51, 775–801.

Eddon, M. (2010). Intrinsicality and hyperintensionality. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 82, 314–336.

Fine, K. (2010). Towards a theory of part. Journal of Philosophy, 107, 559–589.

Fine, K. (2012). A guide to ground. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Forrest, P. (2006). The operator theory of instantiation. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 84, 213–228.

Giberman, D. (2015a). A topological theory of fundamental concrete particulars. Philosophical Studies, 172, 2679–2704.

Giberman, D. (2015b). Junky non-worlds. Erkenntnis, 80, 437–443.

Goodman, N., & Quine, W. V. (1947). Steps toward a constructive nominalism. Journal of Symbolic Logic, 12, 105–122.

Incurvati, L. (2012). How to be a Minimalist about Sets. Philosophical Studies, 159, 69–87.

Kim, J. (1998). Mind in a physical world. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kim, J. (2002). The layered model: Metaphysical considerations. Philosophical Explorations, 5, 2–20.

Kment, B. (2014). Modality and explanatory reasoning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1983). New work for a theory of universals. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 61, 343–377.

Lewis, D. (1986a). On the plurality of worlds. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Lewis, D. (1986b). Against structural universals. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 64, 25–46.

Lewis, D. (1991). Parts of classes. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Lewis, D. (1993). Mathematics is magethology. Philosophy Mathermatica, 3, 3–23.

Lewis, D. (2002). Tensing the copula. Mind, 111, 1–13.

Melia, J. (1992). An alleged disanalogy between numbers and propositions. Analysis, 52, 46–48.

Melia, J. (2008). A world of concrete particulars. In D. Zimmerman (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaphysics (Vol. 4). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, E. (2014). Schaffer on the action of the whole. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 114, 365–370.

Nolan, D. (2014). Hyperintensional metaphysics. Philosophical Studies, 171, 149–160.

Nolan, D. Forthcoming. It’s a kind of magic: lewis, magic, and properties. Synthese.

O’Conaill, D., & Tahko, T. E. (2012). On the common sense argument for monism. In P. Goff (Ed.), Spinoza on monism. New York: Palgrave.

Oppenheim, P., & Putnam, H. (1958). Unity of science as a working hypothesis. In H. Feigl, M. Scriven, & G. Maxwell (Eds.), Minnesota studies in the philosophy of science (Vol. 2). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Paseau, A. (2009). Reducing arithmetic to set theory. In Ø. Linnebo & O. Bueno (Eds.), New waves in philosophy of mathematics. New York: Palgrave.

Rosen, G. (2010). Metaphysical dependence: grounding and reduction. In R. Hale & A. Hoffman (Eds.), Modality: Metaphysics, logic, and epistemology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosen, G. (2015). On the nature of certain philosophical entities. In B. Loewer & J. Schaffer (Eds.), A companion to David Lewis. Oxford: Blackwell.

Rueger, A., & McGivern, P. (2010). Hierarchies and levels of reality. Synthese, 176, 379–397.

Schaffer, J. (2003). Is there a fundamental level? Noûs, 37, 498–517.

Schaffer, J. (2009). Spacetime the one substance. Philosophical Studies, 145, 131–148.

Schaffer, J. (2010a). Monism: The priority of the whole. Philosophical Review, 119, 31–76.

Schaffer, J. (2010b). The internal relatedness of all things. Mind, 119, 341–376.

Schaffer, J. (2010c). The least discerning and most promiscuous truthmaker. The Philosophical Quarterly, 60, 307–324.

Schaffer, J. (2013). The action of the whole. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 87, 67–87.

Sider, T. (1996). Naturalness and arbitrariness. Philosophical Studies, 81, 283–301.

Sider, T. (2006). Bare particulars. Philosophical Perspectives, 20, 387–397.

Sider, T. (2012). Writing the book of the world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Trogdon, K. (2013). An introduction to grounding. In M. Hoeltje, B. Schnieder, & A. Steinberg (Eds.), Varieties of dependence. Munich: Philosophia Verlag.

Trogdon, K. (2017). Priority monism. Philosophy Compass, 12, 1–10.

Trogdon, K. Forthcoming. Inheritance arguments for fundamentality. In R. Bliss, & G. Priest (Eds.) Reality and its structure: Essays in fundamentality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wang, J. (2016). Fundamentality and modal freedom. Philosophical Perspectives, 30, 397–418.

Williams, R. (2007). The possibility of onions worlds: rebutting an argument for structural universals. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 85, 193–203.

Acknowledgements

We presented versions of this paper at conferences at the Jean Nicod Institute (May 2016) and Rutgers University (November, 2016)—thanks to our audience members for helpful feedback. And we wish to thank in particular Mark Balaguer, Ricki Bliss, Einar Bohn, Ben Caplan, Michael Della Rocca, Louis deRosset, Dan Giberman, Jonathan Schaffer, Ted Sider, Gideon Rosen, and anonymous referees for their help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Trogdon, K., Cowling, S. Prioritizing Platonism. Philos Stud 176, 2029–2042 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1109-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-018-1109-4