Abstract

One version of the Humean Theory of Motivation holds that all actions can be causally explained by reference to a belief–desire pair. Some have argued that pretense presents counter-examples to this principle, as pretense is instead causally explained by a belief-like imagining and a desire-like imagining. We argue against this claim by denying imagination the power of motivation. Still, we allow imagination a role in guiding action as a script. We generalize the script concept to show how things besides imagination can occupy this same role in both pretense and non-pretense actions. The Humean Theory of Motivation should then be modified to cover this script role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

On our usage, ‘pretense’ refers to certain behaviors—typically bodily movements—that, we later argue, rise to the level of action. Imagination is a purely mental activity, either individual or collective, that accompanies much pretense.

A few clarifications: First, as is the case with causal accounts of other fundamental concepts, this causation must be “non-deviant” or “in the right sort of way”. Second, in subsequent uses of ‘action’ we drop the qualification ‘intentional’. ‘Action’ is to be understood as something of a philosopher’s term of art. We take actions to be the kinds of things that have explanations in both the causal and rationalization senses. Compare with Davidson (1963/2002).

Arguments for the Motivation-as-Desire Thesis are made by Hume (1978, Book II, Part III, Sect. III), Smith (1987; 1994, Chap. 4), and Mele (1989). As with much of action theory this thesis also traces back to Aristotle, who claimed that, “Intellect itself, however, moves nothing, but only the intellect which aims at an end and is practical.” NE, Book VI (W.D. Ross translation).

Stocker (1979) offers examples of this type: “Through spiritual or physical tiredness, through accidie, through weakness of body, through illness, through general apathy, through despair, through inability to concentrate, through a feeling of uselessness or futility, and so on, one may feel less and less motivated to seek what is good…More generally, something can be good and one can believe it to be good without being in a mood or having an interest or energy structure which inclines one to seek or even desire it.” (pp. 744, 745).

The most prominent and detailed defense of a Humean account of pretense is provided by Nichols and Stich (2003). Their main accomplishment, with regard to pretense, is the development of a cognitive architecture for imagination and pretense. Our aim is slightly different. While the work of Nichols and Stich is highly commendable for its contributions to uncovering the cognitive structures of the pretending mind, we feel that their account of the motivation for pretense (i.e., why pretenders do anything in the first place) stands in need of further development. We aim to do this by applying broader action-theoretic considerations to the special case of pretense.

Velleman (2000, p. 257).

Velleman (2000, p. 257).

Currie and Ravenscroft (2002, pp. 20–21).

Currie and Ravenscroft (2002, p. 8).

Currie and Ravenscroft (2002, p. 11).

Currie and Ravenscroft (2002, p. 125).

Velleman (2000, p. 259).

Technically, then, the child does not necessarily have a desire to pretend as such or under that description. Instead, the desire is better characterized as a desire to behave as if p (all the while knowing that not-p). Future occurrences of “a desire to pretend” should be read with this clarification in mind.

Richert and Lillard (2004).

See Perner et al. (1994).

See Lillard et al. (2000).

Leslie (1987) argues, to the contrary, that young children pretenders do possess a concept of pretense. He states, “Pretending oneself is thus a special case of the ability to understand pretense in others…In short, pretense is an early manifestation of what has been called theory of mind” (p. 416). Though this position is compatible with a Humean account of pretending, we do not think it is supported by the empirical evidence.

Indeed, Currie and Ravenscroft, Anti-Humeans themselves, express their reservations about Velleman’s argument in stating that, “In all sorts of situations we act skillfully and creatively on the basis of beliefs and desires that make little or no conscious impact on us.” (2002, p. 124).

Why the ‘typically’ qualification? Because there are some exceptions—the desires we are indifferent to, say, due to depression. Again, see Stocker (1979). Such exceptions are not intrinsically or essentially motivating, as they do not motivate at all. Other examples might include desires that the agent believes she cannot satisfy for either logical or practical reasons. Examples here include desires to square the circle or to travel to a distant galaxy. (We thank an anonymous referee for these possibilities.) But if these “desires” do not motivate her at all (or even dispose her to such motivation), then for that very reason we think they are better classified as wishes. Alternatively, one could argue that such desires, in spite of the agent’s beliefs, do motivate her to try to do something to satisfy them. But this issue is tangential to our central thesis. Our central thesis is that if a desire motivates, the motivation is intrinsic to the desire. Nothing about these desires that fail to motivate contradicts this assertion.

One might argue that the existence of such exceptions shows that desires in general are not intrinsically or essentially motivating. After all, if desires can fail to motivate, then it seems that there is something else (extrinsic to the desire) that bestows motivating power to them. But we find this form of argument unconvincing. When desires motivate, as they typically do, it is not in virtue of some additional feature. It is the desire itself that has intrinsic motivational powers. So we allow that there are some desires that are not intrinsically motivating, but desires typically are intrinsically motivating.

This account of desire-like imaginings is due to Walton (1990), though he writes of quasi-emotions rather than desire-like imaginings.

Currie and Ravenscroft (2002, p. 118).

Velleman (2000, p. 262).

We thank Jack Lyons for this way of putting the objection.

They are not sufficient for causing action as intention (the will, an executor, etc.) is needed as well. Plus there are cases of weakness of the will, depression and other psychological maladies, and lower-level physical implementation “defeaters”, each of which can thwart the actualizing of rational action even in cases where that action is willed. These other mental features that contribute to the causation of action in no way rationalize the action, however. The rationalization of action is exhausted by guider-motivator pairs.

Currie is explicit about this: “We might resist the idea that there are desire-like imaginings as well as belief-like ones by saying that imagining is a unitary state that incorporates elements both of belief and desire in it, in which case it would be better to speak of ‘imaginary besires’. But the belief-like and desire-like elements in imagination do seem to be separable” Currie (2002, pp. 204–205).

Nichols and Stich (2003, p. 37) (italics in original).

Lillard (2002, p. 188).

Our use of ‘script’ should be contrasted with its use in psychology (e.g., Abelson 1981) to refer to a stereotype for behavior. Our scripts, such as beliefs and imaginings, do not fit this definition. There are certainly things besides stereotypes that guide action, so obviously our usage is broader than this established use of ‘script’ from psychology. (Though we think that our use includes many stereotypes—see Sect. 4.3). Our scripts also should not be thought of as inflexible or pre-set.

As far as its motivation is concerned, we deny that there is a fundamental difference between the pretense of children and that of adults. Of course, adults will have different motives in virtue of having different concepts, ambitions, etc., but this is beside the point. This view contrasts with that of Velleman (2000), which argues that young children, but not adults, are motivated to pretend directly by their imagination (pp. 262–263). In contrast, we are offering a unified account of pretense.

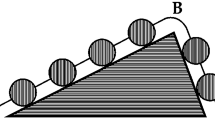

It is important to realize that the specific nature of the actor’s behaviors—the words she says, her entrance and exit, etc.—are not accounted for by beliefs. The script guides her to these words, entrances, and exits, without mediation by her beliefs. In this sense, they provide a model for action. Again, it would be old-fashioned Humean dogmatism to insist that the actor also has some belief to the effect that “The playwright wants me to enter now, then say such-and-such, and then exit”. Instead, the script guides straight away.

See, for example, Walton’s (1990) account of props as generators of fictional truths (pp. 35–43, in particular).

In this regard, our view resembles the role Sayre-McCord (1992) allows for external normative rules, or even the behavior of others, in guiding our actions. He writes: “Normative rules can figure as well, though, in explanations where their effects on a person’s behavior are unmediated by her beliefs about the rules. Sticking with the example of traffic laws, we might explain why a particular person is driving within the speed limit by noting that she is disposed to drive at roughly the same speed as those around her, and that those around her have slowed to 55 mph because they noticed what she did not—a new speed limit sign” (p. 61). We prefer to think of the driving behavior of others as the relevant script here, though there might be cases in which normative rules directly rationalize and causally explain action. Our view is a generalization of his point. Many external things, not just normative rules, can causally/rationally explain our actions without mediation by belief.

One might worry that the constituents of reasons-explanations must possess propositional content, and that these external scripts are not the kinds of things that can possess propositional content. We prefer to argue in the other direction, citing external scripts as evidence that the constituents of reasons-explanations need not bear propositional content. Of course, this is a significant and controversial claim, with obvious analogues in epistemology, that we will not defend here. But, note that our position should also be welcomed by those who hold that the non-propositional elements of imaginings can guide our pretense.

It is awkward, and perhaps inappropriate in some sense, to speak of knowledge as truth-directed given that it necessarily hits its target. But, please allow us this broader use. Truth-directed guiders either aim at or necessarily hit their targets.

References

Abelson, R. P. (1981). Psychological status of the script concept. American Psychologist, 36(7), 715–729.

Aristotle. Nicomachean ethics.

Clark, A. (2003). Natural-born cyborgs: Minds, technologies, and the future of human intelligence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), 7–19.

Currie, G. (2002). Imagination as motivation. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 102(3), 201–216.

Currie, G., & Ravenscroft, I. (2002). Recreative minds. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Davidson, D. (1963/2002). Actions, reasons, and causes. Reprinted in his Essays on actions and events (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Harris, P. (2000). The work of the imagination. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hume, D. (1978). A treatise of human nature (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Leslie, A. (1987). Pretense and representation: The origins of “theory of mind”. Psychological Review, 94(4), 412–426.

Lillard, A. (2002). Pretend play and cognitive development. In U. Goswami (Ed.), Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Lillard, A., Zeljo, A., Curenton, S., & Kaugers, A. (2000). Children’s understanding of the animacy constraint on pretense. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46, 21–44.

Lopes, D., & Kieran, M. (Eds.). (2003). Imagination, philosophy and the arts. London: Routledge.

Mele, A. (1989). Motivational internalism: The powers and limits of practical reasoning. Philosophia, 19, 417–436.

Nichols, S., & Stich, S. (2000). A cognitive theory of pretense. Cognition, 74, 115–147.

Nichols, S., & Stich, S. (2003). Mindreading. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Perner, J., Baker, S., & Hutton, D. (1994). Prelief: The conceptual origins of belief and pretence. In C. Lewis & P. Mitchell (Eds.), Children’s early understanding of mind. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Richert, R., & Lillard, A. (2004). Observers’ proficiency at identifying pretense acts based on behavioral cues. Cognitive Development, 19, 223–240.

Sayre-McCord, G. (1992). Normative explanations. Philosophical Perspectives, 6, 55–71.

Smith, M. (1987). The Humean theory of motivation. Mind, 96, 36–61.

Smith, M. (1994). The moral problem. Oxford: Blackwell.

Stocker, M. (1979). Desiring the bad: An essay in moral psychology. The Journal of Philosophy, 76, 738–753.

Velleman, D. (2000). The possibility of practical reason. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Walton, K. (1990). Mimesis as make-believe: On the foundations of the representational arts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wimmer, H., & Perner, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition, 13, 103–128.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dustin Stokes and an anonymous referee for very helpful comments on this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Funkhouser, E., Spaulding, S. Imagination and other scripts. Philos Stud 143, 291–314 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9348-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9348-z