Abstract

In the 1930s Otto Selz developed a novel approach to the psychology of perception which he called “synthetic psychology of wholes”. This “synthetic psychology” is based on a phenomenological description of the structural relationships between elementary items (tones, colors, smells, etc.) building up integral wholes. The present article deals with Selz’s account of spatial cognition within this general framework. Selz Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 114, 351–362 (1930a) argues that his approach to spatial cognition delivers answers to the long-discussed question of the epistemological status of the laws of geometry. More specifically he tries to derive (a subset of) the Euclidean axioms from the structural laws valid for phenomenal space. After a brief description of the discussion of the status of geometry in the 1920s/1930 (section 2), the present article explains Selz’s understanding of “phenomenology” (section 3). Section 4 then deals with Selz’s attempt to derive the Euclidean laws from the structural phenomenological laws of space. Selz’s attempted derivation suffers from some formal shortcomings, which however can be repaired. The question arises, though, whether the necessary improvements do not rely upon more intricate geometric intuitions and thus render Selz’s attempt to base geometry upon the phenomenology of spatial cognition circular.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Selz (1881–1943) originally studied law and later philosophy and psychology in Munich under Theodor Lipps and in Bonn under Oswald Külpe. Being of Jewish descent, he was deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp where he was killed in 1943. A collection of his basic writings on the psychology of perception and thinking (Selz 1991) has been edited by Alexandre Métraux and Theo Herrmann, who also give a brief account of his life and work in the introduction to their edition. An extensive historiographic study of Selz’s psychology has been provided by Seebohm (1970) in his PhD dissertation. Today Selz is mainly remembered for his impact upon Popper’s philosophy of science and epistemology (ter Hark 2003). Furthermore, he is seen as a forerunner of the “cognitive revolution” (van Strien and Faas 2004) because of his contribution to “Denkpsychologie”.

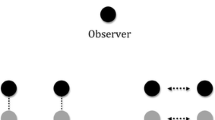

In the first section of his article from 1934 Selz explains the differences between his psychology of wholes and the gestalt psychology of the Berlin school (represented by Wolfgang Köhler) and that of the Leipzig school (represented by Felix Krueger) by means of their different analyses of the circle shape.

Cf., the first pages of Einstein’s address to the Prussian Academy of Science from 1921 where he deals with “axiomatics”. His views as explained there are obviously inspired by Hilbert’s work.

In his talk about “Geometry and experience” (cited in the previous footnote) Einstein (1921, 6) explicitly explains: “[…] we may consider it [namely: the thus interpreted geometry] as just the most ancient branch of physics.”

This talk belongs to a series of lectures, which Hilbert held at the University of Göttingen in the winter term 1922/23 and which have been recorded and worked out by his then assistant Wilhelm Ackerman.

Selz (1934, 378, fn. 1), too, cites this sentence; however, he is not aware that, if taken in isolation, it is not an appropriate statement of Hilbert’s view on geometry; cf. the following paragraph of the main text.

The principle at issue is equivalent to the axiom of parallels. Hilbert (1922, 89) suggests that Gauss, who had measured the sum of the angles of a large triangle determined by the peaks of three mountains of the Harz, did so in order to empirically check the validity of that axiom. As is shown by Breitenberger (1984), however, this interpretation of Gauss’s geodesic research is untenable. Nevertheless, it seems that Gauss held views on the epistemological status of geometry similar to those of Hilbert. In a letter to the astronomer Olbers he wrote: “Perhaps in another life we reach at other insights into the nature of space, which are inaccessible for us now. Until then one would have to rank geometry not together with arithmetic, which is purely a priori, but for instance together with mechanics” (Gauss 1900, 177).

As the inventory of Selz’s literary estate indicates he took sixteen pages of excerpts from Carnap’s PhD thesis from 1922, which deals with this debate (Selz 2013, card D II 1). The intensiveness of the discussion is testified by the bibliography of Carnap’s dissertation, which comprises no less than 275 titles, most of them from the two first decades of the 20th, the rest from the second half of the nineteenth century.

Though the idea of natural space is provided to us by perception, it is not “space as perceived,” cf. p. 9 below.

It is clear from the context that the term descriptive psychology is not used here in Brentano’s sense but rather refers just to psychology as an empirical discipline aiming at adequate descriptions and explanations of psychic phenomena.

Cf. Giorello and Sinigaglia (2007) for a succinct presentation of Husserl’s views on the perception and constitution of space as developed in his lectures on “Ding und Raum”.

There is no indication either that Selz has been accustomed with Husserl’s considerations in the posthumously article published 1939 by Eugen Fink in the Revue international de philosophie (1939), which considers the problem of the origin of geometry from a perspective quite different from that taken by Selz.

As is obvious from a letter (from 9 April 1922) to Hermann Weyl, Husserl considered Becker’s analysis of physical geometry as definitive. According to Husserl (1994, 293f), Becker had shown that Einstein’s theory when complemented with Weyl’s infinitesimal geometry is “the only possible and ultimately understandable one” and he asks the rhetorical question: “What will Einstein say to this when it is proven that nature postulates a relativistic structure because of a priori reasons of phenomenology rather than because of positivistic principles?”

Selz received his “Habilitation” in 1912 under Oswald Külpe, who had moved from Würzburg to Bonn in 1909.

As regards Husserl’s knowledge of Selz’s work it may be remarked here that he seems to have been acquainted at least with Selz’s contribution to the psychology of thinking. In July 1922 Karl Bühler, when leaving the Technical University of Dresden for a professorship in Vienna, asked Husserl to support Selz as his successor in Dresden (Husserl 1994, 45). He refers Husserl to Selz’s “new great book,” i.e., to the monograph from 1922. Already two days later Husserl (1994, 247) sent a letter to Selz asking him for a copy of the book and received it September 7th; cf. Schuhmann (1977, 183).

Stumpf has been the academic teacher of “nearly all of the founders or leading co-workers of Gestalt theory” (Ash 1998, 34). As will be shown in the present section, he also had a decisive impact upon Selz’s synthetic psychology of wholes, which Selz considered to provide an answer to the question how gestalts are built up by simpler items, a question left open, according to Selz, by the gestalt psychlogists; cf. section 1 above.

More detailed and comprehensive explanations were given by Stumpf in an extensive monograph on epistemology published posthumously in two volumes in 1939 and 1940; cf. Stumpf (1939/40). However, Stumpf’s monograph was probably unknown to Selz, who since 1939 lived as an emigrant under difficult conditions in Amsterdam.

Besides phenomenology Stumpf assumes two other neutral foundational disciplines, namely “eidology” (“Eidologie”) – concerned with such structures (“Gebilde”) as concepts and states of affairs – and “general relation theory” (“allgemeine Verhältnislehre”) – dealing with relational concepts such as similarity, identity, part (Stumpf 1906, 32ff, 37ff).

Such dependencies play an important role in Stumpf’s theory of space and space perception. Thus, for instance, spatial extension and color mutually depend on each other: neither can we represent extensionless color nor colorless extension. Stumpf (1873, ch. I, § 5) works out his account of such dependencies in his theory of psychological parts, which is the starting point for Husserl’s (1901, II/1, ch. III, §§ 2–4) celebrated investigation concerning parts and wholes.

Cf. Stumpf (1939, 173): “The analysis of the content of the senses in itself has still the last word to say.”

Stumpf refers to Dilthey’s Academy lecture from 1894, the very lecture which gave rise to the Dilthey-Ebbinghaus-controversy on the status of psychology and its proper methodological procedure; cf., e.g., Galliker (2010). Stumpf remarks however that he would like to have separated Dilthey’s notion of a “teleological connection of life”

(“teleologischen Lebenszusammenhanges”) from that of a structural law. On Husserl’s view upon the controversy cf. Husserl (1968, § 1).

“What E. Husserl originally understood by ‘pure phenomenology’ was nothing else than Brentano’s descriptive or phenomenological psychology, especially the analysis of thought experiences [Denkerlebnisse].” In the printed text the first component Denk- of the composite noun Denkerlebnisse is highlighted by letter-spacing.

A similar criticism is put forward by Husserl’s modern interpreter Mulligan (1995, 168), who explains that “Husserl lost interest in describing the things and processes in the real world.” Therefore Mulligan, in his article on Husserl’s work on perception, restricts himself to the early works, which “are relatively free of the mysteries of Husserl’s transcendental and idealist turns.”

“Like the color of a visual perception, its location, too, is a sensory phenomenon.”

Thus, the entry “Phänomen” in Schmid’s (1798, 420) dictionary of Kantian terminology consists in nothing more than a reference to the article “Erscheinung”.

Kant is quite explicit about this: he mentions color as something which “belongs to sensation” and points to the spatial features of extension and form as something which remains “if we separate from the representation that which the understanding thinks about it […] as well as that which belongs to sensation” Kant (1902ff, III, 50) = (1998, 156).

In 1764 Lambert had published a comprehensive treatise New Organon by which he hoped more completely to achieve that what Aristotle and Bacon intended in their “Organa”. Lambert’s treatise comprises four parts the last of which is called “Phenomenology or The Doctrine of Appearance” (“Phänomenologie oder Lehre von dem Schein”) and contains the “theory of appearance and its influence upon the correctness and incorrectness of human cognition” (Lambert 1764, 645).

Two years later, in 1772, in a letter to Marcus Herz, the term “Die Phänomologie [sic] überhaupt” re-occurs as the heading of the first part in a sketch for a planned comprehensive work on Die Grenzen der Sinnlichkeit und Vernunft (Kant 1902ff, X, 129). Thus “phenomology” was intended to take that role in the planned work which later in the Critique of Pure Reason is taken over by the transcendental aesthetics.

In the English translation the German term “Sehding” is rendered as “visual object” and “Gesichtsempfindung” is translated simply by “perception”; cf. Hering (1942, 2).

That the “geometry of visibles” is non-Euclidean had been suggested already in 1764 by Thomas Reid, thus 60 years before the possibility of non-Euclidean geometries was recognized by the mathematicians Lobachevsky and Bolyai in the 1820s; cf., e.g., Daniels (1972).

The English rendering of the term Gewühl by swarm is not quite adequate since there are orderly swarms (e.g., of birds) while a “Gewühl” always lacks any structure. The term occurs only in the first edition of the Critique. A few pages later Kant (1902, IV, 89) = (1989, 239) speaks of the “unruly heaps” (“regellose Haufen”) which our representations would build if they “reproduced one another […] just as they fell together.” This passage again has not been taken over to the Critique’s second edition.

Selz thus seems to ascribe to Kant what Falkenstein (1995, 78f) calls the “heap thesis” according to which “sense dumps its deliverances on us all in a heap”. For a complete interpretation of Kant, this thesis has furthermore to be supplemented either by the hypothesis that space is an inborn mechanism for ordering the items of this heap (Falkenstein’s “form as mechanism”; 1995, 77–81) or an orderly pattern of “ready-made, empty containers” to be filled with them (Falkenstein’s “form as representation”). Falkenstein argues in his book that such an interpretation, while it fits for Kant’s dissertation (from 1770), misrepresents Kant’s position in the Critique. According to him (1995, 93), Kant, in his later works, considered the ordered “spatiotemporal sensory manifold” not to be the product of “any cognitive processing” but rather “to be originally received as the immediate effect of impression of the senses” [emphasis in the original]. Such a position would be much closer to that of Stumpf and Selz.

As has been explained in the previous section (cf. p. 9 above), Selz here follows his Berlin teacher Stumpf. On the difference between Stumpf’s view on sensation and perception and those of the neo-Kantians cf. Dewalque (2014).

Selz adds that psychology continued in that state “until the present time” (“jusqu’à l’époque áctuelle”). For Selz, it is a recent discovery of phenomenology due to the work of Hering and Stumpf that there are also necessary structural laws of constitution governing perception.

One may object here that Kant (1902ff, III, 116f) = (1998, 291) assumes that sensations (of the same kind) are ordered by their “degree” (“Grad”), which is an “intensive magnitude” (“intensive Größe”). Such orderings are, if not identical, so very similar to Selz’s increasements of degree of strength; cf. section 4.2 below. However, Kant does not state structural laws for intensive magnitudes.

However, it may happen – and does so in the case of Hilbert’s own system of Euclidean geometry because of his “axiom of completeness” (Hilbert 1899, 30, Axiom V.32) – that all models are isomorphic to each other. Such a theory is called categorical. Identifying isomorphic models, one may say that a categorical theory has a uniquely defined topic.

The notion of a “phenomenal continuum” is analyzed in more depth by Selz in his article posthumously published in 1949.

It is rather difficult to provide an adequate English translation for Selz’s German term. “Increases of number” would be misleading since Selz considers the notion of number to be derived from that of “Mengensteigerung”. Nor would “Increases of amount” fit since it would include increases in the quantity of continuous masses while Selz is thinking of the phenomenal growth of collections of discrete “units” (Selz 1941b). Hence I have borrowed the technical term cardinality from set theory here.

Strictly speaking, the expression cyclical series – as well as Selz’s zyklische Reihe – involve a contradictio in adjecto since the notion of a series normally is understood to comprise linearity.

Selz (1930a, 35) says that they are finite, thereby overlooking the possibility that such series may be dense and thus infinite.

This is not the case for the notion of relation as applied in situation theory: “There is no reason to suppose the argument places of an arbitrary relation are intrinsically ordered” (Barwise 1981, 180).

Hering’s methodological procedure markedly differs from that of his opponent Helmholtz, who, in the second volume of his Treatise of physiological Optics, prepares his treatment of color in §§ 19 and 20 by two paragraphs considering, respectively, the “Stimulation of the Organ of Vision” (§ 17) and the “Stimulation by Light” (§ 18), cf. Helmholtz (1856: II, 3–41) = (1924: II, 1–46). There is a whole series of further differences between Helmholtz and Hering on the issue of color as well as on other matters of visual perception, cf. Turner (1994).

Selz himself does not mention this obvious possibility. However, he (1930a, 355) observes that “[t]he perception of curved surfaces, e.g., the surfaces of spheres, requires a three-dimensional system of local qualities.”

Note that this center must lack a local tone since it is the point of indifference of any antagonistic series of increase composed of two directions opposite to each other. Selz explicitly says that the two characteristic tones of an antagonistic series simultaneously “drop out” at the point indifference. There is thus no local tone HERE and natural space has a punctual hole at its center.

It should be noted here that Selz, being not trained as a mathematician, probably tried to get expert advice for his geometrical endeavors. One card (1930a, A I 5 3) of his literary estate mentions “6 pages and 2 sheets” of handwritten notes from a conversation with Arthur Rosenthal, then professor at the University of Heidelberg and an expert in the axiomatics of geometry.

Affine geometry may be characterized as that part of Euclidean geometry which can be developed without the use of the notion of congruence.

Intuitively, a great circle of a sphere is a circle on it which has maximal circumference. Thus, on the sphere of local tones, the equator leading through FRONT, LEFT, BACK, and RIGHT back to FRONT is a great circle as is, e.g., the path leading from FRONT via TOP, BACK, and BOTTOM back to FRONT.

A linear order is Dedekind complete if it cannot be split up into two halves such that both the first one lacks a last and the second one a first element. Thus, e.g., each rational number either is smaller or greater than the square root of 2, which itself is “irrational”. This square root thus divides the rational numbers into two disjoint subsets one of which has no greatest and the other no smallest element. The smaller-greater-order of the rational numbers is thus not Dedekind complete though it is dense. The question whether the concept of Dedekind completeness makes sense for phenomenal continua is discussed by Brentano (1976, 3–59) in a treatise “Vom Kontinuierlichen” from 1914. It should be noted that Dedekind himself by no means considered it necessary that space (“der Raum”) is continuous (in his sense), cf. Dedekind (1872: 11) = (1996: 772) He points out that it would still have many of its usual properties even if it were not continuous. If one identifies space with the collection of all points which can be constructed by straightedge and compass, as Kant – according to Friedman (1996) – does, then that space (as seen from the viewpoint of modern mathematics) contains “holes” and would thus not be continuous; cf. Friedman (1985, 464).

References

Allesch, G. J. v. (1931). Zur nicht-euklidischen Struktur des phänomenalen Raumes. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Ash, M. G. (1998). Gestalt psychology in German culture 1890–1967. Holism and the quest for objectivity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barwise, J. (1981). The situation in logic. Stanford: CSLI.

Bauch, B. (1923). Wahrheit, Wert und Wirklichkeit. Leipzig: Meiner.

Becker, O. (1923). Beiträge zur phänomenologischen Begründung der Geometrie und ihrer physikalischen Anwendungen. Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung, VI, 381–560. – 2nd edition (as book). Tübingen: Niemeyer 1973.

Boring, E. G. (1942). Sensation and perception in the history of experimental psychology. New York: Appleton-Century.

Breitenberger, E. (1984). Gauss's geodesy and the axioms of parallels. Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 31, 273–289.

Brentano, F. (1907). Untersuchungen zur Sinnesphysiologie. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot. – Reprint (R. M. Chisholm & R. Fabian, Eds.). Hamburg: Meiner 1979.

Brentano, F. (1976). Philsophische Untersuchungen zu Raum, Zeit und Kontinuum (S. Körner & R.M. Chisholm, eds.). Hamburg: Meiner.

Carnap, R. (1922). Der Raum. Berlin: Reuther & Reichard.

Daniels, N. (1972). Thomas Reid's discovery of non-Euclidean geometry. Philosophy of Science, 39, 219–234.

Dedekind, R. (1872). Stetigkeit und Irrationalzahlen. Braunschweig: Vieweg. – Reprint. 10th ed. Braunschweig: Vieweg 1969.

Dedekind, R. (1996). Continuity and irrational numbers. In From Kant to Hilbert: A Scource book in the foundations of mathematics (pp. 765–778). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dewalque, A. (2014). La richesse du sensible: Stumpf contre les néokantiens. In F. Calori (Ed.), De la Sensibilité: Les Estéthique de Kant (pp. 261–284). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Dilthey, W. (1894). Ideen über eine beschreibende und zergliedernde Psychologie. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1309–1407.

Einstein, A. (1921). Geometrie und Erfahrung. Erweiterte Fassung des Festvortrages gehalten an der Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin am 27. Januar 1921. Berlin: Springer.

Falkenstein, L. (1995). Kant's intuitionism. A commentary on the transcendental aesthetic. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Friedman, M. (1985). Kant's theory of geometry. Philosophical Review, 94, 455–506.

Galliker, M. (2010). Die Dilthey-Ebbinghaus-Kontroverse. In U. Wolfradt, M. Kaiser-El Safti, & H. P. Brauns (Eds.), Hallesche Perspektiven auf die Geschichte der Psychologie (61–78). Lengerich: Pabst.

Gauss, C. F. (1900). Werke. Achter Band. Ed. by the Königliche Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. Leipzig: Teubner.

Giorello, G., & Sinigaglia, C. (2007). Space and movement. On Husserl's geometry of the visual field. In Rediscovering phenomenology. Phenomenological essays on mathematical beings, physical reality, perception and consciousness (pp. 103–123). Dordrecht: Springer.

Helmholtz, H. v. (1856). Handbuch der physiologischen Optik (3 Vols). Hamburg: Voss. – Reprint (p. 2003). Hildesheim: Olms.

Helmholtz, H. v. (1924). Treatise on Physiological Optics (J. P. C. Sothall Ed.). Rochester NY: Optical Society of America. – Reprint. New York: Dover 1962.

Hering, E. (1879). Der Raumsinn und die Bewegung des Auges. In L. Hermann (Ed.), Handbuch der Physiologie der Sinnesorgane. Erster Theil. Gesichtssinn (343–602). Leipzig: Vogel.

Hering, E. (1920). Grundzüge der Lehre vom Lichtsinn. Berlin: Springer.

Hering, E. (1942). Spatial sense and movements of the eye (C. A. Radde, Trans.). Baltimore: American Academy of Optometry. .

Hering, E. (1964). Outlines of a theory of the light sense. (L. M. Hurvich and D. Jameson, Trans.). Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Hilbert, D. (1899). Die Grundlagen der Geometrie. Leipzig: Teubner. – Centenary edition. Stuttgart: Teubner 1999.

Hilbert, D. (1922). Wissen und mathematisches Denken. Vorlesung von Prof. David Hilbert W.S. 1922/23. Ausgearbeitet von W. Ackermann. Göttingen: Mathematisches Seminar der Universität Göttingen.

Huntington, E. V. (1917). The continuum and other types of serial order. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Husserl, E. (1901). Logische Untersuchungen (Husserliana XVIII, XIX/1, 2). Halle an der Saale: Niemeyer.

Husserl, E. (1903/04). Bericht über deutsche Schriften zur Logik in den Jahren 1895–1899 (Husserliana XXII, 162–258). Archiv für systematische Philosophie, 113–132, 237–259, 393–408, 523–543, 101–125(1904).

Husserl, E. (1911). Philosophie als strenge Wissenschaft (Husserliana XXV, 3-62). Logos, I, 289–340.

Husserl, E. (1913). Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie (Husserliana III.1, 2). Halle a.d.S.: Niemeyer.

Husserl, E. (1939). Die Frage nach dem Ursprung der Geometrie als intentional-historisches Problem (Husserliana VI, pp, 365-386). Revue Internationale de Philosophie, 1, 203–225.

Husserl, E. (1968). Phänomenologische Psychologie (Husserliana IX). Vorlesungen Sommersemester 1925 (Husserliana IX). Dordrecht: Springer.

Husserl, E. (1970). Logical investigations. 2 vols. (J. N. Findlay, Trans.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Husserl, E. (1973). Ding und Raum (Husserlina XVI). Vorlesungen 1907. Dordrecht: Springer.

Husserl, E. (1994). Briefwechsel. Bd. 7. Wissenschaftlerkorrespondenz. Dordrecht: Kluwer/Springer.

Kant, I. (1902ff). Gesammelte Schriften. Ed. by the Prussian (later German) Academy of Science. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kant, I. (1998). Critique of pure reason. (P. Guyer and A. W. Wood, Trans.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kant, I. (2011). Metaphysical foundations of natural science. (M. Friedman, Trans.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Klatzky, R. (1998). Allocentric and egocentric spatial representations. Definitions, distinctions, and interconnections. In C. Freksa, C. Habel, & K. F. Wender (Eds.), Spatial knowledge. An interdisciplinary approach to representing and processing spatial knowledge (pp. 1–17). Berlin: Springer.

Lambert, J. H. (1764). Neues Organon. Leipzig: Wendler. – Reprint (G. Schenk, Ed.). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag 1990.

Lask, E. (1912). Die Lehre vom Urteil. Tübingen: Mohr.

Mulligan, K. (1995). Perception. In B. Smith & D. Woodruff Smith (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Husserl (pp. 168–238). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schapp, W. (1910). Beiträge zur Phänomenologie der Wahrnehmung. Göttingen: Kästner. – Reprint. 5th edition. Frankfurt a. M.: Klostermann 2013.

Schmid, C. C. E. (1798). Wörterbuch zum leichteren Gebrauch der Kantischen Schriften. Jena: Cröker. – Reprint (N. Hinske, Ed.). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Schuhmann, K. (1977). Husserl-Chronik: Denk- und Lebensweg Edmund Husserls. The Hague: Nijhoff.

Seebohm, H. B. (1970). Otto Selz: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Psychologie. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Heidelberg.

Selz, O. (1912). Husserls Phänomenologie und ihr Verhältnis zur psychologischen Fragestellung. Trial lecture (Probevorlesung) held at the Rheinische Friedrich-Universität Bonn. In Seebohm (1970: Appendix E, 73–87).

Selz, O. (1922). Zur Psychologie des produktiven Denkens und des Irrtums. Eine experimentelle Untersuchung. Bonn: Cohen.

Selz, O. (1929). Essai d'une nouvelle théorie psychologique de l'espace, du temps et de la forme. Journal de Psychologie Normale et Pathologique, 26, 337–353.

Selz, O. (1930a). Die psychologische Strukturanalyse des Ortskontinuums und die Grundlagen der Geometrie. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 114, 351–362.

Selz, O. (1930b). Die Struktur der Steigerungsreihen und die Theorie von Raum, Zeit und Gestalt. In K. Bühler (Ed.), Bericht über den XI. Kongress für experimentelle Psychologie in Wien (pp. 27–45). Leipzig: Fischer.

Selz, O. (1930c). Von der Systematik der Raumphänomene zur Gestalttheorie. Archiv für die Gesamte Psychologie, 77, 527–551.

Selz, O. (1934). Gestalten und Steigerungsphänomene. Archiv für die Gesamte Psychologie, 77, 319–394.

Selz, O. (1936). Le problèmes génétique de la totalité phenomenologique de la construction des touts et de formes. Journal de Psychologie Normale et Pathologique, 33, 88–113.

Selz, O. (1941a). Die Aufbauprinzipien der phänomenalen Welt. Acta Psychologica, 5, 7–35. – Reprint. Selz (1991, 173–194).

Selz, O. (1941b). Die phänomenalen Grundlagen des Zahlbegriffes. Nederlands Tijdskrift voor Psychologie, 9, 147–191.

Selz, O. (1949). Die Analyse des phänomenalen Kontinuums. Ein Beitrrag zur synthetischen Psychologie der Ganzen. Acta Psychologica, 6, 91–125.

Selz, O. (1991). Wahrnehmungsaufbau und Denkprozeß. (A. Métraux & T. Herrmann. Eds.). Bern: Huber.

Selz, O. (2013). Katalog des Nachlasses von Otto Selz. Retrieved from https://ub-madoc.bib.uni-mannheim.de/33331. Date of access 28–01–2019.

Spiegelberg, H. (1972). Phenomenology in Psychology and Psychiatry: A Historical Introduction. Evanston IL: Northwestern Universtity Press.

Stumpf, C. (1873). Über den psychologischen Ursprung der Raumvorstellung. Leipzig: Hirzel. – Reprint. Amsterdam: Bonset 1965.

Stumpf, C. (1883). Tonpsychologie. 2 Vols. Leipzig: Hirzel. – Reprint. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2013.

Stumpf, C. (1906). Zur Einteilung der Wissenschaften. Abhandlungen der königlich preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-historische Abhandlungen, 5, 1–94.

Stumpf, C. (1939/40). Erkenntnislehre. Leipzig: Barth. – Reprint. Lengerich: Pabst 2011.

ter Hark, M. (2003). Popper, Otto Selz and the rise of evolutionary epistemology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Turner, R. S. (1994). In the Eye’s Mind. Vision and the Helmholtz-Hering Controversy. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

van Strien, P. J., & Faas, E. (2004). How Otto Selz became a forerunner of the cognitive revolution. In T. C. Dalton & R. B. Evans (Eds.), The life cycle of psychological ideas (pp. 175–201). New York: Kluwer.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank two anonymous referees for their insightful comments and for their advice, which helped me to shape the final version of the present paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Robering, K. Otto Selz’s phenomenology of natural space. Phenom Cogn Sci 19, 97–121 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-019-09614-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-019-09614-9