Abstract

Background Potential drug–drug interactions are important factors resulting in adverse drug reactions or therapeutic failure. Therefore, potential drug–drug interactions need to be identified to prevent the related risk and improve drug safety. Objective This study was designed to determine the prevalence of potential drug–drug interactions and investigate the association of potential drug–drug interactions with characteristics in outpatient prescriptions. Setting A large-scale general university hospital in Jinshan District of Shanghai, China. Method The retrospective study was conducted on data obtained from prescriptions containing two or more drugs, written for outpatients older than 18 years. They were screened for potential drug–drug interactions using Lexi-Interact in UpToDate, Stockley’s Drug Interactions and Medicine Specification in the order of priority. Main outcome measure Drug–drug interactions with C, D, X risk rating and clinical parameters recorded at the prescriptions. Results 16,120 prescriptions were screened for the presence of potential drug–drug interactions and 4882 (30.29%) prescriptions containing 6667 potential drug–drug interactions were identified. Among 6667 potential drug–drug interactions, 90.81% (6054/6667), 8.49% (566/6667), 0.70% (47/6667) potential drug–drug interactions belonged to the risk category of C, D and X, respectively. Male, old age and polypharmacy increased the likelihood of potential drug–drug interactions. The most frequently prescribed drugs responsible for potential drug–drug interactions included pioglitazone, dihydrocodeine, thalidomide, sotalol, amiodarone and amlodipine. The predominant potential adverse outcome of potential drug–drug interactions was the increased central nervous system suppression function with the mechanism of reinforced pharmacological effects. Conclusion This study showed that potentially significant drug–drug interactions in outpatients were prevalent in real-world practice. Considering the risk of potential clinical consequences related to potential drug–drug interactions, it is necessary to implement the computerized surveillance and warning systems with drug–drug interactions databases as well as develop the clinical guidelines regarding the widespread potential drug–drug interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impacts on practice

-

Drug–drug interactions are frequent in outpatients. Health professionals including physicians and pharmacists should raise awareness of the potential impact of drug–drug interactions.

-

It is important to incorporate the clinical pharmacists into the healthcare team to routinely screen the potential drug–drug interactions.

-

A computerized warning systems with smarter screening software may be beneficial in reducing the potential risk of drug–drug interactions.

-

Further research is needed to develop clinical guidelines regarding the widespread potential drug–drug interactions along with their potential adverse outcomes and management strategies.

Introduction

Potential drug–drug interactions (pDDIs) are defined as reactions likely to occur that may alter the effect or safety of two or more drugs concomitantly administered [1]. Drug–drug interactions (DDIs), which induce approximately 22% of drug withdrawal and adverse drug reactions-related hospital admissions, are one of the preventable drug related problems with the risk of deteriorating the therapeutic effect, causing adverse drug reactions and resulting in treatment failure or even death [2]. Therefore, it is of great significance to identify pDDIs to prevent the related risk and improve the clinical medication safety.

Several factors contribute to the occurrence of DDIs in populations, such as age, comorbidities, polypharmacy, nutritional status, and genetic constitution of an individual [3, 4]. Therefore, DDIs are of concern especially in elderly patients with comorbidities. It has been reported that the risk of adverse drug reactions resulting from DDIs increased 50% in people taking five medications, and 100% in those taking eight drugs [5].

DDIs are highly prevalent not only in outpatients but also in hospitalized patients especially in ICU [6, 7], oncology [8,9,10] and hematology [11, 12]. The prevalence of pDDIs varies from 16% to 96% in different studies [13,14,15,16]. Given the lack of investigation on the epidemiology of DDIs in the outpatients of Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University, the present study aimed to gain insight into the real-world prevalence of pDDIs in outpatient prescriptions and classify the severity of the interactions.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of pDDIs in outpatients by screening the prescriptions using Lexi-Interact in UpToDate, Stockley’s Drug Interactions and Medicine Specification in the order of priority. Besides, we investigated the association of pDDIs with variables in prescriptions.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University (IEC-2020-S05). As the study was conducted from prescription records, individual informed consent was not applicable.

Method

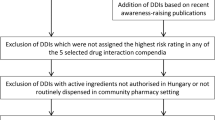

This cross-sectional retrospective study was conducted in the outpatients of Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University, which is a large-scale general hospital integrating medical service, education and research. The prescriptions for analysis were collected from June 1st to July 1st in 2019. The study subjects were all outpatients older than 18 years, treated with at least two drugs. The data included diagnosis, demographic data (such as age and gender), prescribed drugs with the exclusion of herbal medicines due to rare knowledge of drug–herbal interactions and the high compositional variability inherent to herbal drugs [17]. Compound preparations which contain multiple pharmacologically active ingredients were analyzed individually according to each ingredient.

pDDIs have been examined based on the Lexi-Interact in UpToDate and classified into five categories according to the clinical significance as A (no known interaction), B (no action needed), C (monitor therapy), D (consider therapy modification) and X (avoid combination). If the drugs were not included in Lexi-Interact, we referred to Stockley’s Drug Interactions and Medicine Specification. The priority of retrieving order was Lexi-Interact, Stockley’s Drug Interactions and Medicine Specification.

The data were recorded in a Microsoft Office Excel file. Descriptive statistics were applied to analyze the demographics of total outpatients, number of drugs, and pDDIs characteristics. The values were presented as numbers and percentages as appropriate. To investigate the potential risk factors of pDDIs, the logistic regression was performed to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of pDDIs based on the patient’s characteristics. Binary variables were defined for prescriptions exposing to at least one C-, D-, or X-interaction. The effect of gender on the occurrence of pDDIs was analyzed in the study. Categories for age were defined as follows: young (18–39), middle-aged (40–64), and elderly (≥ 65). Categories for number of drugs in each prescription were defined as 2–3, 4–6, and 7 or more. Another variable in the analysis was patient sex. A p value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All data analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software (version 18.0, IBM, USA).

Results

Population characteristics

A total of 16,120 prescriptions were evaluated for the presence of pDDIs. Clinical data of the study population was provided in Table 1. Male patients comprised 48.68% of the study population. Mean age of the patients was 57.30 ± 16.11 years, where 36.11% of the patient population were elderly individuals aged ≥ 65 years as well as young patients of age < 40 years and middle-aged patients (40–64) accounted for 16.67% and 47.22% respectively. The most commonly number of medications prescribed for each patient was no more than six, accounting for 94.89%.

Prevalence of pDDIs and factors associated with pDDIs

A total of 4882 prescriptions (30.29%) were identified with 6667 pDDIs. And pDDIs fell into category C, D, and X in a proportion of 90.81% (6054/6667), 8.49% (566/6667) and 0.70% (47/6667), respectively (Fig. 1).

The logistic regression showed that sex, age and number of prescribed medicines were independently associated with the occurrence of pDDIs (p < 0.01) (Table 1). Female patients had lower risk of developing pDDIs compared with the male patients (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.79–0.91). Middle-aged and elderly patients were found to have the risk of pDDIs increased by 2.03 (95% CI 1.82–2.26) and 2.22 (95% CI 1.98–2.49), respectively. The number of prescribed medicines was also a risk factor for the occurrence of pDDIs (p < 0.01).

Statistical analysis showed that 1201 prescriptions (24.6%) were identified with more than one pDDIs even up to 6 pDDIs per prescription, 761 (15.59%) prescriptions with 2 pDDIs per prescription and 341 (6.98%) prescriptions with 3 pDDIs per prescription (Table 2). The characteristics and distributions of those prescriptions were shown in Table 2.

Potential clinical consequences and mechanisms of pDDIs

Table 3 demonstrated the potential clinical consequences and related mechanisms of top 20 pDDIs in category D. The most frequent drug pairs of pDDIs with category D were pioglitazone-glimepiride (34 cases). The most frequent potential clinical consequence of the identified pDDIs was enhanced central nervous system suppression function. The predominant mechanism was reinforced pharmacological effects (57.64%).

As shown in Table 4, the majority of pDDIs with category X were related to thalidomide with the potential clinical consequence of enhanced central nervous system suppression function through the mechanism of reinforced pharmacological effects. The most frequent interaction found in category X was the simultaneous administration of ebastine and thalidomide.

Discussion

This retrospective real-world study showed that among the 16,120 prescriptions screened by Lexi-Interact, 30.29% had at least one potentially DDI in the outpatient department of Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University with 90.81%, 8.49%, 0.70% pDDIs falling into the risk category of C, D and X, respectively. We identified that male, old age and polypharmacy increased the risk of pDDIs. The most frequent potential clinical consequence of category D and X pDDIs was enhanced central nervous system suppression function with the mechanism of reinforced pharmacological effects.

A cross-sectional study conducted by Mohammad Ismail et al. had showed that 22.3% of outpatients had pDDIs in a tertiary care hospital of Peshawar, Pakistan [14]. Janja Jazbar et al. conducted a retrospective nationwide study in Slovenia and reported 24.1% of the population was exposed to pDDIs with 9.3% D or X risk rating [18]. An institution-based cross-sectional study in Northwestern Ethiopia found that 34.5% of prescriptions with two or more medicines had at least one pDDIs [19]. The discrepancy among the prevalence of pDDIs in these studies may be attributable to the study design, drug prescribing pattern, screening system, criteria of pDDIs, and so on.

In our study, a higher percentage of pDDIs was found in male, which was in line with the previous findings [19, 20]. However, there are inconsistent results regarding the impact of gender on pDDIs. A cross-sectional study conducted in the Brazil found that being male was associated with a lower likelihood of pDDIs [21]. Besides, other studies found no significant difference in terms of sex [3, 22]. The cause of inconsistent results may be due to the study design and the longer lifespan in women [23].

In the present study, age was another variable associated with higher occurrence of pDDIs, specifically elderly aged over 65 compared to the young (18–39), which was in accordance with the previous study [19]. Due to concomitant ailments, the elderly patients take higher number of drugs at a time. Furthermore, they are more sensitive to pharmacokinetic effects.

As expected, the result of logistic regression analysis showed that polypharmacy (more than 3 medications per prescription) was a risk factor for the occurrence of pDDIs, which was in agreement with the pilot study of hospitalized pediatric patients conducted by Fabiola Medina-Barajas et al. [4]. Several studies had drawn a consistent conclusion that the increasing amount of medications was a risk factor for presenting drug interactions [24,25,26].

The results of the present study showed that a dominant proportion of identified pDDIs were found to be involved with the drugs of cardiovascular system, nervous system and endocrine system such as pioglitazone, propafenone, valproate, sotalol, amiodarone, warfarin, fluoxetine, clopidogrel, thalidomide, amlodipine, dihydrocodeine and codeine. Some previous studies showed inconsistent consequences. It was identified that levofloxacin, diclofenac, aspirin and clopidogrel were the dominant drugs for DDIs in outpatients [6], while Netsanet Diksis et al. had reported that aspirin, clopidogrel and enalapril were the three main drugs that caused pDDIs among hospitalized cardiac patients [27]. The reason for these contradictions may be due to variable drugs utilization pattern and the resources of drug information.

The most common interaction of category D and X in our study was pioglitazone + glimepiride, ebastine + thalidomide, respectively. Enhanced central nervous system suppression function was the most frequent clinical consequences of the identified pDDIs. However, the previous study found that the most common interactions in outpatient department were ibuprofen + levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin + diclofenac, aspirin + atenolol, and diclofenac + levofloxacin with the potential adverse outcomes such as seizures, bleeding, QT-interval prolongation, arrhythmias, tendon rupture, hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia and so on [14]. This inconsistency may be attributed to DDIs screening system and different drugs prescribing pattern.

This is the first study to analyze the prevalence of pDDIs in the outpatients of Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University, which nearly covers all clinical departments. However, there were some limitations in our study. First, this was a retrospective study which failed to evaluate the real-life clinical consequences of pDDIs. Besides, as a single-center study, the treatment regimens and the patient profile may not be generalizable. Second, the information of each patient was restricted to only one prescription sheet. We did not obtain totality data such as herbal medicines, OTC drugs and vitamins taken by outpatients, which might contribute to the underestimation of pDDIs. Third, there are several available DDI databases with the disparities in the inclusion of pDDIs and the severity grading [28]. However, only one screening database was employed to estimate the prevalence of pDDIs. To improve the precision of the detection, it is suggested that two or more screening databases should be used to evaluate pDDIs.

Clinical guidelines are generally applicable to single disease. However, the cumulative impact from multiple clinical guidelines is rarely considered [29]. Hence, it is necessary to develop clinical guidelines regarding the widespread pDDIs along with their potential adverse outcomes and management strategies [14]. Furthermore, this study will raise awareness of the importance of implementing the computerized warning systems with smart DDI databases as well as incorporating the clinical pharmacists into the healthcare team to routinely screen the pDDIs.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the real-world prevalence of pDDIs in outpatients at a rate of 30.29% with the most common interaction of category C. Gender, age and polypharmacy were risk factors significantly related to the occurrence of pDDIs. Further, enhanced central nervous system suppression function was most frequently observed as potential clinical consequences of the pDDIs in our study. Therefore, it is necessary to implement appropriate strategies so as to avoid or reduce these relevant pDDIs, such as computer-based warning systems of pDDIs, serum concentration monitoring, regular follow-up and accelerated clinical guides.

References

Magro L, Moretti U, Leone R. Epidemiology and characteristics of adverse drug reactions caused by drug–drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2012;11:83–94.

Song YK, Oh JM. Nationwide prevalence of potential drug–drug interactions associated with non-anticancer agents in patients on oral anticancer agents in South Korea. Support Care Cancer. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520019052211.

Daggupati SJV, Saxena PUP, Kamath A, Chowta MN. Drug–drug interactions in patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy and the impact of an expert team intervention. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096019009496.

Medina-Barajas F, Vázquez-Méndez E, Pérez-Guerrero EE, Sánchez-López VA, Hernández-Cañaveral II, Gabriel A RO, et al. Pilot study: evaluation of potential drug-drug interactions in hospitalized pediatric patients. Pediatr Neonatol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedneo.2019.11.006.

Johnell K, Klarin I. The relationship between number of drugs and potential drug-drug interactions in the elderly: a study of over 600,000 elderly patients from the Swedish prescribed drug register. Drug Saf. 2007;30:911–8.

Ismail M, Khan F, Noor S, Haider I, Haq IU, Ali Z, et al. Potential drug–drug interactions in medical intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:1052–6.

Janković SM, Pejčić AV, Milosavljević MN, Opančina VD, Pešić NV, Nedeljković TT, et al. Risk factors for potential drug-drug interactions in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2018;43:1–6.

Tavousi F, Sadeghi A, Darakhshandeh A, Moghaddas A. Potential drug-drug interactions at a referral pediatric oncology ward in Iran: a cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2019;41:E146–51.

Nightingale G, Pizzi LT, Barlow A, Barlow B, Jacisin T, McGuire M, et al. The prevalence of major drug–drug interactions in older adults with cancer and the role of clinical decision support software. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9:526–33.

Tavakoli-Ardakani M, Kazemian K, Salamzadeh J, Mehdizadeh M. Potential of drug interactions among hospitalized cancer patients in a developing country. Iran J Pharm Res. 2013;12:175–82.

Fernández de Palencia Espinosa MÁ, Díaz Carrasco MS, Sánchez Salinas A, de la Rubia Nieto A, Miró AE. Potential drug–drug interactions in hospitalised haematological patients. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2016;23:443–53.

Ribed A, Romero-Jiménez RM, Escudero-Vilaplana V, IglesiasPeinado I, Herranz-Alonso A, Codina C, et al. Pharmaceutical care program for onco-hematologic outpatients: safety, efciency and patient satisfaction. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:280–8.

Al-Azayzih A, Alamoori R, Altawalbeh SM. Potentially inappropriate medications prescribing according to Beers criteria among elderly outpatients in Jordan: a cross sectional study. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2019;17:1439.

Ismail M, Noor S, Harram U, Haq I, Haider I, Khadim F, et al. Potential drug–drug interactions in outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:762.

Mistry M, Gor A, Ganguly B. Potential drug–drug interactions among prescribed drugs in paediatric outpatients department of a tertiary care teaching hospital. J Young Pharm. 2017;9:371–5.

Nusair MB, Al-Azzam SI, Arabyat RM, Amawi HA, Alzoubi KH, Rabah AA. The prevalence and severity of potential drug–drug interactions among polypharmacy patients in Jordan. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28:155–60.

Brantley SJ, Argikar AA, Lin YS, Nagar S, Paine MF. Herb–drug interactions: challenges and opportunities for improved predictions. Drug Metab Dispos. 2014;42:301–17.

Jazbar J, Locatelli I, Horvat N, Kos M. Clinically relevant potential drug-drug interactions among outpatients: a nationwide database study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2018;14:572–80.

Teni FS, Belachew SA, Gebresillassie BM, Birru EM, Wubishet BL, Tekleyes BH, et al. Pattern and appropriateness of medicines prescribed to outpatients at a university hospital in Northwestern Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:3729401.

Guthrie B, Makubate B, Hernandez-Santiago V, Dreischulte T. The rising tide of polypharmacy and drug–drug interactions: population database analysis 1995–2010. BMC Med. 2015;13:74.

Obreli Neto PR, Nobili A, Marusic S, Pilger D, Guidoni CM, Baldoni Ade O, et al. Prevalence and predictors of potential drug-drug interactions in the elderly: a cross-sectional study in the brazilian primary public health system. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012;15:344–54.

Shafiekhani M, Moosavi N, Firouzabadi D, Namazi S. Impact of clinical pharmacist’s interventions on potential drug-drug interactions in the cardiac care units of two university hospitals in Shiraz, South of Iran. J Res Pharm Pract. 2019;8:143–8.

Wastesson JW, Canudas-Romo V, Lindahl-Jacobsen R, Johnell K. Remaining life expectancy with and without polypharmacy: a register-based study of Swedes aged 65 years and older. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:31–5.

Santibáñez C, Roque J, Morales G, Corrales R. Characteristics of drug interactions in a pediatric intensive care unit. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2014;85:546–53.

van Leeuwen RW, Brundel DH, Neef C, van Gelder T, Mathijssen RH, Burger DM, et al. Prevalence of potential drug-drug interactions in cancer patients treated with oral anticancer drugs. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1071–8.

van Leeuwen RW, Swart EL, Boven E, Boom FA, Schuitenmaker MG, Hugtenburg JG. Potential drug interactions in cancer therapy: a prevalence study using an advanced screening method. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2334–41.

Diksis N, Melaku T, Assefa D, Tesfaye A. Potential drug–drug interactions and associated factors among hospitalized cardiac patients at Jimma University Medical Center. Southwest Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312119857353.

Benoist GE, van Oort IM, Smeenk S, Javad A, Somford DM, Burger DM, et al. Drug-drug interaction potential in men treated with enzalutamide: mind the gap. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:122–9.

Dumbreck S, Flynn A, Nairn M, Wilson M, Treweek S, Mercer SW, et al. Drug-disease and drug–drug interactions: systematic examination of recommendations in 12 UK national clinical guidelines. BMJ. 2015;350:h949.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful for the cooperation of staff and support of the hospital.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University (JYQN-LC-202010) to Weifang Ren, “Qi Hang” Project of Jinshan Hospital, Fudan University (2018-JSYYQH-05) and Fourth Training Program for the Outstanding Young Talents, Jinshan Health Commission (JSYQ201904) to Xiaoqun Lv, Key Construction Project on Clinical Pharmacy of Shanghai (2019-1229).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, W., Liu, Y., Zhang, J. et al. Prevalence of potential drug–drug interactions in outpatients of a general hospital in China: a retrospective investigation. Int J Clin Pharm 42, 1190–1196 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01068-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01068-3