Abstract

Background Patients with advanced cancer commonly experience pain and it is least controlled in community settings. Community pharmacists in the UK already offer medicines optimisation consultations although not for this patient group. Objective To determine whether medicines consultations for patients with advanced cancer pain are feasible and acceptable. Setting Community-dwelling patients with advanced cancer pain were recruited from primary, secondary and tertiary care using purposive sampling in one UK city. Methods One face-to-face or two telephone delivered medicines optimisation consultations by pharmacists were tested. These were based on services currently delivered in UK community pharmacies. Feedback was obtained from patients and healthcare professionals involved to assess feasibility and acceptability. Main outcome measure Recruitment, acceptability and drug related problems. Results Twenty-three patients, (range 33–88 years) were recruited, 19 completed consultation(s) of whom 17 were receiving palliative care services. Five received face-to-face consultations and 14 by telephone during which 47 drug related problems were identified from 33 consultations (mean 2.5). Advice was provided for 34 drug related problems in 17 patients and referral to other healthcare professionals for 13 in 8 patients, 2 patients had none. Eleven patients returned questionnaires of which 8 (73%) would recommend the consultations to others. Conclusion The consultations were feasible as patients were recruited, retained, consultations delivered, and data collected. Patients found the 20–30 min intervention acceptable, found a self-perceived increase in medicines knowledge and most would recommend it to others. Community pharmacists were willing to carry out these services however they had confidence issues in accessing working knowledge. Most drug related problems were resolved by the pharmacists and even among patients receiving palliative care services there were still issues concerning analgesic management. Pharmacist-conducted medicines consultations demonstrate potential which now needs to be evaluated within a larger study in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impacts on practice

-

Pharmacist-delivered medicines consultations are feasible and acceptable to cancer patients and have the potential to benefit clinical care.

-

Even for patients under specialist palliative care services, unmet medicines-related needs can be identified by pharmacists.

-

Access to pharmacist care for patients with advanced cancer who are not able to visit the pharmacy in person should be improved.

Introduction

Over half of patients with advanced cancer will experience poorly controlled pain during their last year of life [1, 2]. Only 18% of patients at the end-of-life living in the community describe their pain as well controlled compared with 38% of patients in hospitals and 63% of patients in hospices [3]. Often, community-based patients feel they lack support with their medicines taking and accept experiencing pain [4].

Community Pharmacists are the healthcare professional seen most frequently by patients with cancer (along with community nurses) [5] and are often available in every locality without an appointment. Community pharmacies may be in or near family doctor practices or sometimes in shopping centres or supermarkets and could potentially be an accessible source of medicines support for patients with cancer pain. Medicines optimisation services are provided by community pharmacists in the UK, USA, Australia and New Zealand with the aim of helping patients get the most benefit possible from the medicines they have been prescribed [6,7,8,9,10]. In the UK the two most common are detailed in Table 1.

The World Health Organization Pain ladder provides stepwise guidance for adult pain management [11]. Severe pain can usually be controlled by regular dosing of simple pain killers, adjuncts and sustained-release pain medication with top-up or breakthrough doses in-between but patients need to understand their medicines to gain optimum benefit from them [12, 13]. Pharmacist medicines consultations have been shown to increase patient knowledge and have associated improvements in medicines adherence [14, 15].

Although community pharmacist medicines consultations are rarely carried out with patients experiencing cancer pain, several studies have investigated the contributions they could make [16,17,18,19]. Outcome measures included the quantity of Drug Related Problems (DRPs), recommendations made and an assessment of the appropriateness of recommendations [16,17,18,19,20]. A DRP can be defined as an event or circumstance involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interferes with desired health outcomes [21]. Patient’s perspectives are often difficult to obtain post-intervention from patients with advanced disease due to rapid deterioration and only one study included this [18, 22]. A recent systematic review showed that pharmacist educational interventions are potentially beneficial for patients with cancer pain but further research is needed in this area [23].

Lack of pharmacist confidence to provide services for patients with cancer has been identified as a barrier to service provision [24,25,26]. All previous studies either employed a specialist palliative care pharmacist or provided some sort of additional training, although the content and evidence-base of training was not always reported [16,17,18,19].

Aim

To evaluate pharmacist medicines consultations for patients with advanced cancer and to ascertain their feasibility and acceptability.

Ethics approval

Ethical permission was granted from Leeds West National Health Service and Bradford University Ethical Committee in October 2014 (14-YH-1126 141015). This study was part of the larger Improving the Management of Pain from Advanced Cancer in the Community (IMPACCT) study.

Method

Recruitment site identification

Research ready family doctor practices with practice pharmacistsFootnote 1 were identified and approached. Recruitment commenced in November 2015 and continued until March 2017.

The recruitment process was iterative responding to the levels of identification and recruitment of patients. New and refined recruitment methods were developed, and the local hospital and hospice were invited to be recruitment sites towards the end of the study.

Community pharmacist recruitment

The 10 pharmacies closest to the practices recruited were identified (four from national multiples and six independents) and contact was made with owners or head offices. Nine agreed to take part with one independent stating lack of interest. An interactive briefing session for the pharmacists was developed based on the specific needs of community pharmacists found in previous studies [24,25,26]. Information from a specialist nurse and a cancer support charity was delivered and role plays were carried out with a cancer survivor from our Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) group. Pharmacists and support staff representing all community pharmacies attended the training which was well received.

Patients who used one of the study pharmacies were offered either a telephone-based Medicine Use Review (MUR) or a face-to-face MUR (see Table 1).

Patients who did not use one of the study pharmacies were offered telephone consultations from the Research Pharmacist (RP) using the New Medicine Service (NMS) format allowing the same issues to be discussed over a series of two telephone consultations (see Table 1). Our earlier research showed that patients with advanced cancer were willing to try this [4].

Patient recruitment

In family doctor practices, searches using the study inclusion criteria (see Box 1) were conducted in electronic systems by practice pharmacists. Community pharmacists, district nurses and family doctors were asked to refer suitable patients to the GP practice, where the practice pharmacist screened them and confirmed suitability with their GP. Oncology research nurses at the local hospital were asked to conduct outpatient clinical records searches. The hospital outpatient pharmacy was asked to refer patients to the research nurses. Patients from primary and secondary care recruitment were then invited to take part by letter.

The hospice research nurse, together with the study RP undertook recruitment in the local hospice. Patients about to be discharged or attending outpatient clinics were introduced to the study by their nurse. Those who expressed interest were provided with written information and consented face-to-face by the RP.

All patients gave written consent.

Sample

As this was a proof-of-concept study a formal sample size was not required but we aimed to recruit 25 patients as this was adequate to assess whether it was possible to recruit and retain patients, whether the consultations were deliverable and acceptable to patients and healthcare professionals involved.

Medicines optimisation consultations

The length of each consultation was noted by the pharmacist and any recommendations made to the patient and/or the prescriber were documented contemporaneously, in line with usual practice for NMS and MUR. Consultation records used a study code and did not contain any patient identifiable information.

Patient and pharmacist feedback

Baseline and post-consultation follow-up patient questionnaires were developed based on validated pain measurement tools used in the IMPACCT study [27, 28]. Drafts were piloted with the study PPI group and feedback was obtained. The questionnaire included quantitative and qualitative questions about levels of pain (worst experienced in the last 24 h and at time of questionnaire completion on a 0–10 scale (0 = no pain to 10 = pain as bad as they could imagine). Self-reported knowledge information was also collected. The baseline questionnaire was posted before the consultation with a stamped addressed return envelope. The follow-up questionnaire was sent 2 weeks after the final consultation and included additional questions on self-perceived benefit from the consultation and whether the patient would recommend the medicines consultation to others. Questionnaires are available on request from the author.

Data analysis

Medicines consultation records were coded by the RP using the Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) classification which is a validated system developed by experts to document DRPs, their cause and action taken following their identification [21].

Information from the baseline and follow-up questionnaires was collated and analysed using Excel spreadsheets.

Feasibility

This will be assessed by whether it was possible to recruit and retain patients throughout the study and whether it was possible to train community pharmacists to deliver consultations.

Acceptability

A theoretical framework which was developed based on systematic reviews involving acceptability and inductive and deductive reasoning of reviews and literature is available [29]. The framework details acceptability before (prospective), during (concurrent) and after the intervention (retrospective). This was adapted to assess acceptability of the intervention. Three questions requiring likert responses were included in the questionnaires as a result:

-

1.

I feel I benefitted from the consultation.

-

2.

I was able to ask all the questions I wanted to.

-

3.

I would recommend a pharmacist pain medicines consultation to other people.

Data was also collected on whether the community pharmacists completed the consultations when they were requested to do so. The day after the scheduled consultation, the RP telephoned the community pharmacist and gathered unstructured feedback about the experience of providing the consultation.

Results

128 patients were identified for the study; 47 were confirmed as eligible by their healthcare professional and invited to take part. Twenty-three consented to participate and 19 received the medicines consultations of whom 17 were already receiving specialist palliative care services.Footnote 2 Four patients deteriorated or died before they had consultations. Patients were aged between 33 and 88 (average 64 years old). More detail about recruitment methods is available elsewhere [30].

Four community pharmacists were requested to deliver five consultations, of which all took place. Five patients had a face-to-face MUR from four different community pharmacists (3 independents and 1 multiple) and 14 had two NMS-type consultations from the RP. Five patients were unavailable at the second telephone consultation and required further phone calls. One patient had hearing difficulties and asked for his spouse to be involved in the telephone call to aid communication.

The mean duration of medicines consultations was 31 min for MUR (range 20–60 min) and for the NMS type consultations the mean total time for the two consultations was 18 min (range 9–29 min) per patient.

In total 47 DRPs were identified in 17 patients with a mean of 2.5 per patient (range 0–7, median 2) (see Table 2). Consultations were often multi-faceted (see Exemplar case studies-Box 2) and MURs averaged 1.2 DRPs per patient and the NMS-type averaged 3. Advice was given to 17 patients to resolve 34 DRPs and 13 (for 8 patients) were addressed by referral to other healthcare professionals: 6 to recommend prescribing of additional medication (for pain, constipation or dry mouth), 2 for a concomitant medicines query, 2 to recommend an alternative medicine (for constipation), 1 for an alternative dosage form and 2 to flag up important symptoms to the prescriber.

Full details of the PCNE classification can be found in “Appendix 1” [21].

Feedback from patients

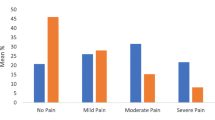

Eleven patients returned both baseline and post-consultation questionnaires. The answers to the three acceptability questions are shown in Table 3 along with other questions regarding pain and self-reported knowledge.

Pre-consultations, the mean pain score was 4.1 (range 0–8) and three patients felt they knew enough about their medicines compared with 4.0 and seven at follow-up. No other medicines education support was reported by patients during the intervention period.

Feedback from community pharmacists

At the follow-up phone call after the consultations three of the four community pharmacists reported having some challenges in carrying out the consultations. Two reported lack of confidence and three had difficulties in retaining knowledge when the consultations were so infrequent.

Difficulties with recruitment

Several methods of recruitment were used of which one (hospice) produced 18 of the 23 participants. Face to face recruitment methods were found to be more effective than by letter and recruitment was more successful where healthcare professionals were engaged in the study. Full details and evaluation of methods used are reported elsewhere [30].

Discussion

This study shows that even for patients receiving specialist palliative care, pharmacist-delivered medicines consultations were feasible and acceptable to patients and had the potential to benefit clinical care.

Feasibility

We found that identification of patients was more difficult than expected so additional methods were developed iteratively. Recruitment and attrition rates were in line with other similar studies [31, 32].

Community pharmacists found it difficult to retain working knowledge regarding cancer and this could potentially be improved if the consultations were carried out more frequently. Creation of referral pathways to community pharmacy were not successful, therefore we also tested telephone provision of medicines consultations by one centralised RP. This was used successfully with a broad age range of patients.

We know from previous research that one in three patients are never referred to specialist palliative care services and we hypothesise that these patients may have greater need for a medicines consultation [4, 33]. Recruitment methods used were less successful in finding those who had not been referred to palliative care. Even though almost all our participants were receiving this; a mean of 2.5 DRPs per patient was found showing a need for extra support even in this group.

Acceptability to patients

All patients who had an NMS-type service (n = 14) agreed to the second consultation after having the first so we deduce that patients found them acceptable.

The majority of consultations were carried out via telephone. This method was acceptable for all patients who received it and some studies show this may even be preferable for some, especially those who are seriously ill [4, 34]. Telephone-based appointments are already used in many community pharmacies and family doctor practices with high levels of patient satisfaction [35,36,37].

Retrospective acceptability can be estimated by perceived effectiveness and self-efficacy. Most patients felt they benefitted from the consultations (which was also found elsewhere), were able to ask all the questions they wanted to and would recommend it to others [35]. There was an increase in patients who felt they knew enough about their medicines following the intervention indicating that knowledge was increased. Pain levels in this patient group can change rapidly due to the nature of the illness although average pain levels remained the same [22]. This may be due to a negation in the expected deterioration over time although on such a small sample it is difficult to draw any such conclusions. Patient evaluation is more likely to be obtained following a one-off intervention so this may have affected our response rates [38].

Acceptability to healthcare professionals

One community pharmacy (n = 10) declined to be involved but all 9 who agreed sent representatives to the voluntary training showing prospective acceptability was generally good. There were a mix of independent and multiple community pharmacies showing a willingness of both groups to take part.

Only one pharmacist (other than the RP) was asked to carry out more than one consultation and although they agreed, this is not enough to signify acceptability at this stage.

Potential to benefit clinical care

As in other studies the most common DRP identified was pain and several participants were not taking simple painkillers as recommended because they had not been prescribed [11, 17]. The next most identified DRP was constipation, again a finding in other studies [16, 17, 20]. Almost three quarters of DRPs concerned treatment effectiveness. Seventeen MRPs related to patients not understanding how and why to take medications after they had been prescribed. In some cases, medication was ineffective, and the patient required a stronger dose or a change in treatment.

Pharmacists were able to resolve the majority of DRPs with the patient; eight of the 19 patients were referred to nurses or GPs. Many of the referrals would have been prevented if the pharmacist conducting the consultations had been a prescriber with access to medical records. In several previous studies, the pharmacist was either a trained prescriber or was part of a palliative care team that could organise changes in prescribing [17,18,19,20, 39]. Acceptance of DRP recommendations by prescribers was unknown and future studies need to track this.

Limitations of the study

Most patients taking part already had access to palliative care professionals and associated medicines support. If patients had been recruited before referral to palliative care, there may have been an opportunity to educate at an earlier stage.

Patients receiving two consultations were hospice outpatients who had already been referred to palliative care and therefore are more likely to have greater need for symptom control; this may have affected the type and number of DRPs found compared with those who had not been referred. It may be that this group would have more DRPs than those not yet referred to palliative care or it may be that they would have already had more opportunity to get DRPs addressed. This would benefit from further testing across both patient groups.

Acceptability was measured before, during and after the consultations. The numbers of participants, pharmacists and healthcare professionals returning questionnaires was small and this may affect the validity of the results.

Conclusion

The consultations were feasible to deliver, and patients found them acceptable. Community pharmacists were willing to provide these services although found working knowledge to be problematic due to the infrequent nature of the consultations. Further evaluation of clinical and cost-effectiveness is now needed.

Pharmacist medicines consultations were able to identify a substantial number of DRPs in patients with advanced cancer pain. Problems with inadequate pain relief and associated side effects were most prevalent and the majority of these could be addressed by the pharmacist even in patients already receiving specialist palliative care.

Notes

Practice pharmacist refers to a role within family doctor or General Practitioner (GP) practices which aids with prescribing, audit, costing and sometimes performing clinical roles. They were involved in this study to allow electronic records to be checked to identify patients and assess eligibility criteria.

Specialist Palliative Care Services are received by patients who have been referred and usually involves access to multidisciplinary palliative care healthcare professionals to provide symptom control.

References

van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol/ESMO. 2007;18(9):1437–49.

Breivik H, Cherny N, Collett B, de Conno F, Filbet M, Foubert AJ, et al. Cancer-related pain: a pan-European survey of prevalence, treatment, and patient attitudes. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol/ESMO. 2009;20(8):1420–33.

ONS. National survey of bereaved people (VOICES): 2014. ONS, London. 2015. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthcaresystem/bulletins/nationalsurveyofbereavedpeoplevoices/2015-07-09. Accessed Nov 2017.

Edwards Z, Blenkinsopp A, Ziegler L, Bennett MI. How do patients with cancer pain view community pharmacy services? An interview study. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(4):507–18.

Bennett MI, Closs SJ, Chatwin J. Cancer pain management at home (I): do older patients experience less effective management than younger patients? Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(7):787–92.

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Guidelines for pharmacists providing home medicines review (HMR) services. 2011. https://www.ppaonline.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/PSA-Guidelines-for-Providing-Home-Medicines-Review-HMR-Services.pdf. Accessed 3rd April 2019.

Pharmaceutical Society of New Zealand Incorporated. Medicines use reviews (MUR). 2018. https://www.psnz.org.nz/Category?Action=View&Category_id=261. Accessed 29 March 2018.

Isetts B. Integrating medication therapy management (MTM) services provided by community pharmacists into a community-based accountable care organization (ACO). Pharm (Basel). 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy5040056.

PSNC. Medicines use review (MUR). London. 2017. http://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/advanced-services/murs/. Accessed 14 Nov 2017.

PSNC. NMS medicines list. In: Services and Commissioning. PSNC, London. 2017. http://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/advanced-services/nms/. Accessed 14 Nov 2017.

WHO. WHO’s cancer pain ladder for adults. In: Cancer. World Health Organisation. 2017. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/. Accessed 14 Nov 2017.

Paice JA. Cancer pain management and the opioid crisis in America: how to preserve hard-earned gains in improving the quality of cancer pain management. Cancer. 2018.

Valeberg BT, Miaskowski C, Hanestad BR, Bjordal K, Moum T, Rustøen T. Prevalence rates for and predictors of self-reported adherence of oncology outpatients with analgesic medications. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(7):627–36.

Lowe CJ, Raynor DK, Purvis J, Farrin A, Hudson J. Effects of a medicine review and education programme for older people in general practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50(2):172–5.

Department of Health. Understanding and appraising the new medicines service in the NHS in England. (2014) University of Nottingham. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/~pazmjb/nms/downloads/report/files/assets/common/downloads/108842%20A4%20Main%20Report.v4.pdf. Accessed 3 April 2019.

Needham DS, Wong IC, Campion PD, Hull, East Riding Pharmacy Developmnet G. Evaluation of the effectiveness of UK community pharmacists’ interventions in community palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002;16(3):219–25.

Atayee RS, Best BM, Daniels CE. Development of an ambulatory palliative care pharmacist practice. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(8):1077–82.

Jiwa M, Hughes J, O’Connor M, Tuffin P. Field testing a protocol to facilitate the involvement of pharmacists in community based palliative care. Aust Pharm. 2012;31(1):72–6.

Hussainy SY, Box M, Scholes S. Piloting the role of a pharmacist in a community palliative care multidisciplinary team: an Australian experience. BMC Palliat Care. 2011;10:16.

Wilson S, Wahler R, Brown J, Doloresco F, Monte SV. Impact of pharmacist intervention on clinical outcomes in the palliative care setting. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28(5):316–20.

Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe Foundation (PCNE). Classification for drug related problems V8.02. 2017. https://www.pcne.org/news/68/pcne-drp-classification-now-802. Accessed 3 April 2019.

Hackett J, Godfrey M, Bennett MI. Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study. Palliat Med. 2016;30(8):711–9.

Edwards Z, Ziegler L, Craigs C, Blenkinsopp A, Bennett MI. Pharmacist educational interventions for cancer pain management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Pharm Pract. 2019.

O’Connor M, Hewitt LY, Tuffin PH. Community pharmacists’ attitudes toward palliative care: an Australian nationwide survey. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(12):1575–81.

Hussainy SY, Beattie J, Nation RL, Dooley MJ, Fleming J, Wein S, et al. Palliative care for patients with cancer: what are the educational needs of community pharmacists? Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(2):177–84.

Savage I, Blenkinsopp A, Closs SJ, Bennett MI. ‘Like doing a jigsaw with half the parts missing’: community pharmacists and the management of cancer pain in the community. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(3):151–60.

Allsop MJ, Wright-Hughes A, Black K, Hartley S, Fletcher M, Ziegler LE, et al. Improving the management of pain from advanced cancer in the community: study protocol for a pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e021965.

Cleeland CS. Measurement of pain by subjective report. Advances in pain research and management. New York: Raven Press; 1989.

Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of health care interventions: a theoretical framework and proposed research agenda. Br J Health Psychol. 2015.

Edwards Z, Bennett M, Petty D, Blenkinsopp A. Evaluating the effectiveness of recruitment methods of patients with advanced cancer. Int J Pharm Pract (in press).

Sygna K, Johansen S, Ruland CM. Recruitment challenges in clinical research including cancer patients and their caregivers. A randomized controlled trial study and lessons learned. Trials. 2015;16:428.

Corner J, Halliday D, Haviland J, Douglas HR, Bath P, Clark D, et al. Exploring nursing outcomes for patients with advanced cancer following intervention by Macmillan specialist palliative care nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(6):561–74.

Ziegler LE, Craigs CL, West RM, Carder P, Hurlow A, Millares-Martin P, et al. Is palliative care support associated with better quality end-of-life care indicators for patients with advanced cancer? A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e018284.

Car J, Sheikh A. Telephone consultations. BMJ. 2003;326(7396):966–9.

Brant H, Atherton H, Ziebland S, McKinstry B, Campbell JL, Salisbury C. Using alternatives to face-to-face consultations: a survey of prevalence and attitudes in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(648):e460–6.

Moczygemba LR, Barner JC, Brown CM, Lawson KA, Gabrillo ER, Godley P, et al. Patient satisfaction with a pharmacist-provided telephone medication therapy management program. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2010;6(2):143–54.

Barbanel D, Eldridge S, Griffiths C. Can a self-management programme delivered by a community pharmacist improve asthma control? A randomised trial. Thorax. 2003;58(10):851–4.

White CD, Hardy JR, Gilshenan KS, Charles MA, Pinkerton CR. Randomised controlled trials of palliative care—a survey of the views of advanced cancer patients and their relatives. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(13):1820–8.

Wang Y, Huang H, Zeng Y, Wu J, Wang R, Ren B, et al. Pharmacist-led medication education in cancer pain control: a multicentre randomized controlled study in Guangzhou, China. J Int Med Res. 2013;41(5):1462–72.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the role of Dr Liz Breen who acted as mentor for the author.

Funding

The study was funded as part of the Improving the Management of Pain from Advanced Cancer in the CommuniTy (IMPACCT) study which was a National Institute of Health Research programme Grant of which this was part of the Medicines work stream (RP-PG-0610-10114).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to this research and publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Edwards, Z., Bennett, M.I. & Blenkinsopp, A. A community pharmacist medicines optimisation service for patients with advanced cancer pain: a proof of concept study. Int J Clin Pharm 41, 700–710 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-019-00820-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-019-00820-8