Abstract

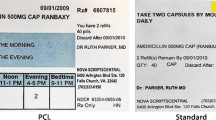

Background Recommendations call for the inclusion of both patient and provider input in the redesign of prescription labels. Pharmacist opinions on prescription warning labels are important because they are the health providers who would eventually distribute and explain the revised labels during medication counseling. They may be the first health provider to notice a patient’s misunderstanding on how to safely use their prescription medications. Objectives To explore the perspectives of patients and pharmacists on five newly designed PWLs, and examine if there were similarities and differences between patients’ and pharmacists’ perspectives. Setting Private room in Wisconsin. Methods A descriptive study using semi-structured 60-min face-to-face individual interviews with patients and pharmacists explored patients and pharmacists’ feedback on five newly designed PWLs. Patients who were 18 years and older, spoke English, and took a prescription medication and pharmacists who filled prescriptions in an ambulatory setting participated in the study. The patient and pharmacist perspectives on the words (content), picture and color (cosmetic appearance), and placement of warning instructions on the pill bottle (convenience) was based on a label redesign framework. Qualitative content analysis was done. Main outcome measure Patient and pharmacist perspectives on the newly designed PWLs. Results Twenty-one patients and eight pharmacists practicing in an academic medical center outpatient setting (n = 5) or retail pharmacy (n = 3) participated. All patients and pharmacists wanted the PWLs positioned on the front of the pill bottle but not the side of the bottle or warning instructions embedded into the main prescription label. Other similarities included participants preferring: (1) pictures closely depicting the instructions and (2) the use of yellow highlighting on the PWL to draw attention to it. There were differences in patient and pharmacist perspectives regarding the addition of ‘Warning’ to the instruction on the PWL with the patient preference to include the word ‘Warning’. Pharmacists thought some PWL pictures had racial stereotypes, but this feedback was never mentioned by patients. Conclusions Patients and pharmacists had different preferences for PWL design changes to improve understandability. Pharmacist preferences did not always correspond with patient preferences. However, patients and pharmacists generally agreed on the preferred location of the PWL on the pill bottle and the use of color for drawing patients’ attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Onder G, Landi F, Liperoti R, Fialova D, Gambassi G, Bernabei R. Impact of inappropriate drug use among hospitalized older adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(5–6):453–9.

Kheir N, Awaisu A, Radoui A, El Badawi A, Jean L, Dowse R. Development and evaluation of pictograms on medication labels for patients with limited literacy skills in a culturally diverse multiethnic population. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2014;10(5):720–30.

Royal S, Smeaton L, Avery AJ, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A. Interventions in primary care to reduce medication related adverse events and hospital admissions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(1):23–31.

Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, Thompson JA, Tilson HH, Neuberger M, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):887–94.

Bootman JL, Cronenwett LR, Bates DW, Califf RM, Cannon HE, Chater RW, et al. Preventing medication errors: quality chasm series. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, Institute of Medicines of the National Academies; 2006.

Kindig DA, Panzer AM, Nielsen-Bohlman L. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004.

Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, Middlebrooks M, Kennen E, Baker DW, et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):847–51.

Wolf MS, Davis TC, Tilson HH, Bass PF, Parker RM. Misunderstanding of prescription drug warning labels among patients with low literacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(11):1048–55.

Shiyanbola OO, Meyer BA, Locke MR, Wettergreen S. Perceptions of prescription warning labels within an underserved population. Pharm Pract. 2014;12(1):387.

Bailey SC, Navaratnam P, Black H, Russell AL, Wolf MS. Advancing best practices for prescription drug labeling. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(11):1222–36.

You WB, Grobman W, Davis T, Curtis LM, Bailey SC, Wolf M. Improving pregnancy drug warnings to promote patient comprehension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(4):318.e1–5.

Wolf MS, Davis TC, Curtis LM, Webb JA, Bailey SC, Shrank WH, et al. Effect of standardized, patient-centered label instructions to improve comprehension of prescription drug use. Med Care. 2011;49(1):96–100.

Hernandez LM. Standardizing medication labels: confusing patients less, workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008.

Wolf MS, Davis TC, Bass PF, Curtis LM, Lindquist LA, Webb JA, et al. Improving prescription drug warnings to promote patient comprehension. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(1):50–6.

Locke MR, Shiyanbola OO, Gripentrog E. Improving prescription auxiliary labels to increase patient understanding. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(3):267–74.

Shiyanbola OO, Smith PD, Mansukhani SG, Huang YM. Refining prescription warning labels using patient feedback: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0156881.

Zargarzadeh AH, Law AV. Design and test of preference for a new prescription medication label. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(2):252–9.

Schectman JM, Nadkarni MM, Voss JD. The association between diabetes metabolic control and drug adherence in an indigent population. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(6):1015–21.

Mohan A, Riley MB, Boyington D, Johnston P, Trochez K, Jennings C, et al. Development of a patient-centered bilingual prescription drug label. J Health Commun. 2013;18(sup1):49–61.

Weiss, BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):514–22.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Lee JY. Investigating the efficacy of an interactive warning for use in prescription labeling strategies. East Lansing: Michigan State University; 2013.

Bailey SC, et al. Developing multilingual prescription instructions for patients with limited english proficiency. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(1):81–7.

Andre AD, Wickens CD. When users want what’s not best for them. Ergonom Des Q Hum Fact Appl. 1995;3(4):10–4.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Wisconsin Research and Education Network for the coordination of all study activities and the recruitment of patients. We appreciate the advice and insights of Theo Raynor during the design of the project. The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the National Institute of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Graduate School through the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation [Grant Number MSN175988].

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shiyanbola, O.O., Smith, P.D., Huang, YM. et al. Pharmacists and patients feedback on empirically designed prescription warning labels: a qualitative study. Int J Clin Pharm 39, 187–195 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0421-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0421-3