Abstract

Objectives

The first ever Pharmacy Workforce Census of pharmacists in Great Britain (GB) was conducted in 2002, and repeated in 2003. Both census surveys aimed to gather empirical data on the employment profile of pharmacists to aid the workforce planning process. The aim of this paper is to compare the work profile and employment destination of two graduate cohorts of pharmacists to explore what changes take place in employment practices and how quickly they occur.

Setting

GB-based pharmacists.

Methods

A two-page postal questionnaire was sent to 38,000 GB-registered pharmacists in August 2003, to provide various data on employment patterns, intentions to work abroad, and desire to practise pharmacy. The pharmacists were contacted using addresses stored on the Pharmaceutical Register, a statutory record of all pharmacists and␣pharmacy premises held by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (RPSGB). A sub-set of this large data set—pharmacists who qualified in 1992 and those who qualified in 1997—was selected for comparison.

Main outcome measure

Sector of employment and strength of desire to practice.

Results

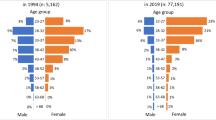

A response rate of 75% was achieved for the overall census, while the response rate from the two graduation cohorts was 62% and 58%. Larger proportions of women compared with men, even after only 5 years of working as a pharmacist, are either not working or work part-time. Among the women, these patterns increase significantly for those with a greater number of years on the Pharmaceutical Register. There is evidence that pharmacists move out of the two main sectors of practice (hospital and community) with increasing years on the Register, and some gender differences in job mobility are observed. The School of Pharmacy from which pharmacists graduate appears to have some effect on practice patterns although more research is needed to explore this further. Desire to practise pharmacy is weaker among those practitioners who work in the community sector of practice, and younger pharmacists are more likely to intend working abroad.

Conclusions

Part-time work patterns are implemented fairly quickly after qualifying, particularly among the women pharmacists. Given that female students account for over 60% of all intake onto pharmacy courses current supply problems will continue if work patterns continue along this trajectory. The ability of the profession to meet current, never mind extended roles, is thus called␣into question.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry. The Report of the Public Inquiry into children’s heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984–1995: Learning from Bristol. CM 5207(1). London: Crown Copyright, 2001

Kendall J, Sibbald B, Ashcroft D, Bradley F, Elvey R, Hassell K et al. Role and uptake of local pharmaceutical services contracts in commissioning community pharmacy services. Pharm J 2005; 274:454–457

Department of Health. A Vision for Pharmacy in the New NHS. 32646 1p 5k Jul 03 (RIC). London: DoH, 2003

Meadows S. Great to be grey: how can the NHS recruit and retain more staff? 1 85717 471 2. London: Kings Fund, 2002

Buchan J. (1998) Further flexing? Issues of employment contract flexibility in the UK nursing workforce. Health Services Manage Res 1998; 11:148–162

Hassell K. The impact of social change on professions—gender and pharmacy in the UK: an agenda for action. Int J Pharm Prac 2000; 8:1–9

Hassell K. Pharmacist work patterns 2003: summary of the 2003 pharmacy workforce census. London: RPSGB, 2004, p. 1-1

Hassell K, Shann P. The national workforce census: (1) Locum pharmacists and the pharmacy workforce in Britain. Pharm J 2003; 270:658–659

Shann P, Hassell K. The national workforce census: (2) Older pharmacists and the pharmacy workforce in Britain. Pharm J 2003; 270:833–834

Hassell K, Shann P. The national workforce census: (3) The part-time pharmacy workforce in Britain. Pharm J 2003; 271:58–59

Hassell K, Nichols L. The national workforce census: (4) Overseas pharmacists—does the globalisation of pharmacy affect workforce supply? Pharm J 2003; 271:183–185

Mullen R, Hassell K. The National Workforce Census: (5) The primary care workforce in Britain. Pharm J 2003; 271:326–327

Hassell K. The National Workforce Census: (6) The gendered nature of pharmacy employment in Britain. Pharm J 2003; 271(550):552

Willett V, Cooper C. Stress and job satisfaction in community pharmacy: a pilot study. Pharm J 1996; 256:94–98

Willett V, Cooper C, Noyce P. The impact of working long hours on employed community pharmacists. Pharm J 1997; 259:R43

Rajah T, Bates I, Davies J, Webb D, Fleming G. An occupational survey of hospital pharmacists in the South of England. Pharm J 2001; 266:723–726

Hassell K, Fisher R, Nichols L, Shann P. Contemporary workforce patterns and historical trends: the pharmacy labour market over the past 40 years. Pharm J 2002; 269:291–296

Bevan S, Hayday S, Callender C. Women professionals in the EC. London: The Law Society; 1993, p. 1–174

Hassell K, Symonds S. The pharmacy workforce. In: Harding G, Taylor K, editors. Pharmacy Practice. London: Taylor and Francis; 2001

Fisher C, Corrigan O, Henman M. Inter-branch mobility of male and female pharmacy graduates in the Republic of Ireland. J Soc Admin Phar 1987; 5(1):1–11

Fisher C, Corrigan O, Henman M. A study of community pharmacy practice: 1 Pharmacists’ work patterns. J Soc Admin Phar 1991; 8(1):15–24

Rees J, Clarke D. Employment, career progression and mobility of recently registered male and female pharmacists. Pharm J 1990; 245:R30

Elworthy P. Work pattern of women pharmacists graduating in 1953. Pharm J 1988; 2:11–16

Tweddell S, Wright D. Determining why community pharmacists choose to leave community pharmacy. Pharm J 2000; 265:R44

Boardman H, Blenkinsopp A, Jesson J, Wilson K. A pharmacy workforce survey in the West Midlands: (4) Morale and motivation. Pharm J 2001; 267:685–690

Boardman H, Blenkinsopp A, Jesson J, Wilson K. A pharmacy workforce survey in the West Midlands: (2) Changes made and planned for the future. Pharm J 2000; 264:105–108

Goldacre M, Lambert TW, Davidson JM. Loss of British-trained doctors from the medical workforce. Med Ed 2001; 35:337–344

Buchan J. Here to stay? International nurses in the UK. Edinburgh: Queen Margaret University College, 2002. p. 1–29

Seccombe I, Buchan J, Ball J. Nurse mobility in Europe: implications for the United Kingdom. Int Migration 1993; 31:125–148

Bellingham C. Facing the recruitment and retention crisis in pharmacy: looking abroad. Pharm J 2001; 267:45–46

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hassell, K. Destination, future intentions and views on practice of British-based pharmacists 5 and 10 years after qualifying. Pharm World Sci 28, 116–122 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-006-9007-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-006-9007-9