Abstract

A number of investigators have studied biblical inerrancy (i.e., the belief that the Bible is inspired by God, free from error, and should be interpreted literally). However, there has been little research on the relationship between biblical inerrancy and mental health outcomes. The purpose of this study is to address this gap in the literature. This is accomplished by estimating a latent variable model that was designed to empirically evaluate the following relationships: (1) Blacks, people with less education, and conservative Christians are more likely to have a strong belief in biblical inerrancy; (2) people with a strong belief in biblical inerrancy are more likely to experience demonic spiritual struggles when they are faced with stressful events; (3) individuals who experience demonic spiritual struggles are more likely to feel that the sacred aspects of their lives have been threatened; and (4) greater sacred loss is associated with more depressive symptoms. Data from a recent nationwide survey (N = 2332) provide support for each of these relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

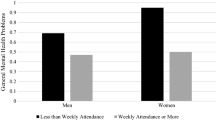

Five types of spiritual struggles are included in the shortened measure that was developed by Exline et al. (2014): divine (“I felt angry at God”), demonic (“I felt as though the devil was trying to turn me away from good), interpersonal (“I was frustrated or annoyed by the actions of religious/spiritual people”), moral struggle (“I worried my actions were morally or spiritually wrong”), and ultimate-meaning (“I felt as though my life had no deep meaning”). We examined the bivariate correlation between belief in biblical inerrancy and each type of spiritual struggles in order to see whether strong biblical inerrancy beliefs are more likely to be associated with demonic struggles. The following correlations were observed: biblical inerrancy and divine struggles (r = .031; ns.), interpersonal struggles (r = −.039; ns.), demonic struggles (r = .238; p < .001), moral struggles (r = .091; p < .001), and struggles involving ultimate-meaning (r = −.023; ns.). These data support our decision to focus specifically on demonic struggles in Fig. 1.

References

Allen, G. E., & Want, K. T. (2014). Examining religious commitment, perfectionism, scrupulosity, and well-being among LDS individuals. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6, 257–264.

Association of Religion Data Archives. (2017). Quick facts. http://www.thearda.com/QuickStats/qs_102_p.asp

Atkinson, W. W. (1908). Mystic Christianity. New York: The Perfect Library.

Barna, G. (2006). The state of the church, 2006. Ventura: The Barna Group.

Bartkowski, J. P., & Hempel, L. M. (2009). Sex and gender traditionalism among conservative Protestants: Does the difference make a difference? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 48, 805–816.

Boyd, G. A., & Eddy, P. R. (2009). Across the spectrum: Understanding issues in evangelical theology. Grand Rapids: Baker Academics.

DeShon, R. P. (1998). A cautionary note on measurement error correlations in structural equation models. Psychological Methods, 3, 412–423.

Disabato, D. J., Kashdan, T. B., Short, J. L., & Jarden, A. (2017). What predicts positive life events that influence the course of depression? A longitudinal examination of gratitude and meaning in life. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41, 444–458.

du Toit, M., & du Toit, S. (2001). Interactive LISREL: User’s guide. Lincolnwood: Scientific Software International.

Ehrman, B. D. (2008). God’s problem: How the bible fails to answer our most important question - why we suffer. New York: Harper Collins.

Ellison, C. G., & McFarland, M. J. (2011). Religion and gambling among U.S. adults: Exploring the role of traditions, beliefs, practices, and networks. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50, 82–102.

Esselmont, C., & Bierman, A. (2014). Marital formation and infidelity: An examination of the multiple roles of religious factors. Sociology of Religion, 75, 463–487.

Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Grubbs, J. B., & Yah, A. M. (2014). The religious and spiritual struggles scale: Development and initial validation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6, 208–222.

Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. (1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. Kalamazoo: John E. Fetzer Institute.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Gruen, R. J., & DeLongis, A. (1986). Appraisal coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 571–579.

Greeley, A., & Hout, M. (2006). The truth about conservative Christians: What they think and what they believe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hood, R. W., Hill, P. C., & Spilka, B. (2009). The psychology of religion: An empirical approach (4th ed.). New York: Guilford.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut points for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Psychological Methods, 1, 130–149.

Koenig, H. G., King, D. E., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Krause, N. (1987). Understanding the stress process: Linking social support with locus of control beliefs. Journal of Gerontology, 42, 589–593.

Krause, N. (2004). Stressors in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 59B, S287–S297.

Krumrei, E. J., Mahoney, A., & Pargament, K. I. (2009). Divorce and the divine: The role of spirituality in adjustment to divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 71, 373–383.

Krumrei, E. J., Mahoney, A., & Pargament, K. I. (2011). Spiritual stress and coping model of divorce: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 973–985.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford.

Murray, H. A. (1962). The personality and career of Satan. Journal of Social Issues, 18, 36–54.

Musu-Gillette, L., Robinson, J., MacFarland, J., Kewal-Ramanni, A., Zhang, A., & Wilkinson-Flicker, S. (2016). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups, 2016. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Pargament, K. I. (1997). The psychology of religious coping: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Guilford.

Pargament, K. I., & Mahoney, A. (2005). Sacred matters: Sanctification as a vital topic for the psychology of religion. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 15, 179–198.

Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Parez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37, 710–724.

Pargament, K. I., Magyar, G. M., Benore, E., & Mahoney, A. (2005a). Sacrilege: A study of sacred loss and desecration and their implications for health and well-being in a community sample. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 44, 59–78.

Pargament, K. I., Murray-Swannk, N. A., Magyar, G. M., & Ano, G. G. (2005b). Spiritual struggle: A phenomenon of interest to psychology and religion. In W. R. Miller & H. D. Delaney (Eds.), Judeo-Christian perspectives on psychology: Human nature, motivation, and change (pp. 245–268). New York: Guilford.

Park, C. L., Wortmann, J. H., & Edmondson, D. (2011). Religious struggle as a predictor of subsequent mental and physical well-being in advanced heart failure patients. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 34, 426–436.

Pearlin, L. I., Menaghan, E., Lieberman, M., & Mullan, J. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Sherkat, D. E. (2010). Religion and verbal ability. Social Science Research, 39, 2–13.

Sherkat, D. E. (2011). Religion and scientific literacy in the United States. Social Science Quarterly, 92, 1134–1150.

Sherkat, D. E., & Ellison, C. G. (1997). The cognitive structure of a moral crusade: Conservative Protestantism and opposition to pornography. Social Forces, 75, 957–980.

Sorotzkin, B. (1998). Understanding and treating perfectionism in religious adolescents. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 35, 87–95.

Stark, R. (2008). What Americans really believe. Waco: Baylor University Press.

Steensland, B., Park, J. Z., Regnerus, M. D., Robinson, L. S., Wilcox, W. B., & Woodberry, R. D. (2000). The measure of American religion: Toward improving the state of the art. Social Forces, 79, 291–318.

Stryker, S. (2001). Traditional symbolic interactionism, role theory, and structural symbolic interactionism: The road to identity theory. In J. H. Turner (Ed.), Handbook of sociological theory (pp. 211–231). New York: Plenum.

Taylor, R. J., & Chatters, L. M. (2010). Importance of religion and spirituality in the lives of African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites. Journal of Negro Education, 79, 280–294.

Thoits, P. A. (1991). Merging identify theory with stress research. Social Psychology Quarterly, 54, 101–112.

Udelman, D. L. (1982). Stress and immunity. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 37, 176–184.

Widaman, K. F. (2012). Exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology Volume 3 (pp. 361–389). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation (40077).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krause, N., Pargament, K.I. Biblical Inerrancy and Depressive Symptoms. Pastoral Psychol 67, 291–304 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-018-0815-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-018-0815-3