Abstract

This study tests the stability of a standard equation for aggregate US imports over the period 1975–2011. It finds evidence of significant parameter instability, though its dating varies with the equation specification and diagnostic. Nonetheless, the analysis finds a significant rise in the long-run income elasticity that is robust across most break dates and specifications. The increase in the long-run income elasticity is consistent with shifts in the composition of aggregate imports toward capital and consumer goods. There is further evidence that vertical specialization may be behind both the structural instability and the apparent rise in the income elasticity of aggregate US imports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Indeed, Bridgman (2012) documents a decline in the materials share of intermediate goods imports in the US and other industrialized economies.

They perform the same exercise for US exports but do not find any evidence of a parallel rise in the corresponding income elasticity.

As Hooper et al. (2000) note, this is an imperfect substitutes model that assumes price homogeneity. It is the workhorse specification for empirical estimates of trade equations and the basis of recent studies of US import behavior (e.g., Crane et al. 2007; Mann and Plück 2007; Chinn 2010) and parameter stability (e.g., Carone 1996 and Hooper et al.).

As reported in Appendix Table 6, the trace statistics indicate the existence of a single cointegrating vector. Single-equation error-correction tests based on four lags also rejected the null of no cointegration.

The DOLS is commonly cited as performing well relative to a number of alternative methods, particularly in small samples. Some evidence to that effect is provided by Montalvo (1995) and Stock and Watson (1993). The DOLS approach assumes there is a single cointegrating relationship, an assumption supported by the results of the Johansen tests reported in the “Appendix”.

The length of the window means that the rolling regressions begin with a subsample that covers 1975–1989 and so do not capture variability in the coefficient estimates in the early part of the sample period. However when the window is shortened to 10 years, there is little variation in the coefficient estimates for the subsamples ending between 1984 and 1988.

The Kejriwal-Perron test is one of the few available procedures for estimating break dates in equations with non-stationary regressors. To my knowledge, this is the first application to a trade equation.

Because this trimming excludes the first and last 15 % of the sample from the testing period, it effectively removes the 2008–09 trade collapse from consideration for structural instability.

The results are not presented in the interest of brevity but are available upon request.

However the CUSUM plots date the instability to around 2000 and the corresponding subsample estimates do not indicate a significant increase in the long-run income elasticity.

As before, these estimates are based on a DOLS with 2 leads and 4 lags. The relative price variables are constructed as the ratio of the import price index for each category to the GDP price index for goods. Though the estimates in Table 5 include the end-use categories for food, feed, and beverages and petroleum, some caution is in order in evaluating the associated results as the imperfect substitutes model is less apt to apply to these sectors.

The magnitude of the weighted-average income elasticity is notably lower than the estimates based on aggregate imports. This may suggest aggregation bias. See Cardarelli and Rebucci (2007) for a discussion of aggregation bias in the context of aggregate US trade.

One of the price elasticities in Table 5 is insignificant from zero and two are positive and significant. For this reason, the disaggregated estimates were not used to construct a weighted-average price elasticity. However, the long-run price elasticity estimates for capital and consumer goods imports are comparatively large, suggesting that the shift toward capital and consumer goods would not necessarily produce a lower price responsiveness for aggregate imports.

Furthermore, this issue is probably best tackled via a cross-sectional approach rather than the time-series methods used here. A cross-sectional approach can avoid complications arising from estimating the time-series effects of measures of global supply or variety that are collinear with demand (Chinn 2010) or smooth series with few inflection points (Gagnon 2007).

References

Aziz J, Li X (2008) China’s changing trade elasticities. China World Econ 16(3):1–21

Bridgman B (2012) The rise of vertical specialization trade. J Int Econ 86(1):133–140

Broda C, Weinstein D (2006) Globalization and the gains from variety. Q J Econ 121(2):541–585

Cardarelli R, Rebucci A (2007) Exchange rates and the adjustment of external imbalances. In: World economic outlook. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC, April, 81–120

Carone G (1996) Modelling the US demand for imports through cointegration and error correction. J Policy Model 18(1):1–48

Cheung C, Guichard S (2009) Understanding the world trade collapse. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 729, OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/220821574732

Chinn M (2005) Doomed to deficits? Aggregate US trade flows re-examined. Rev World Econ 141(3):460–485

Chinn M (2010) “Supply capacity, vertical specialization and trade costs: the implications for aggregate US Trade Flow Equations” prepared for the CESifo conference Trade Costs and International Trade Integration—Past, Present, and Future, June

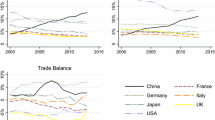

Crane L, Crowley M, Quayyam S (2007) Understanding the evolution of trade deficits: trade elasticities of industrialized countries. Economic Perspectives, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Q4

Escaith H, Lindenberg N, Miroudot S (2010) International supply chains and trade elasticity in times of global crisis. In: Cattaneo O et al (eds) Global value chains in a postcrisis world: a development perspective. World Bank Publications, Washington

Freund C (2009) The trade response to global downturns, Policy Research Working Paper 5015, The World Bank, August

Gagnon J (2007) Productive capacity, product varieties, and the elasticities approach to the trade balance. Rev Int Econ 15(4):639–659

Hooper P, Johnson K, Marquez J (2000) Trade elasticities for the G-7 countries. Princeton Studies in International Economics, No. 87, August

Johnson R, Noguera G (2012) Fragmentation and trade in value added over four decades, mimeo

Kejriwal M, Perron P (2010) Testing for multiple structural changes in cointegrated regression models. J Bus Econ Stat 28(4):503–522

Mann C, Plück K (2007) Understanding the US trade deficit: a disaggregated perspective. In: Clarida R (ed) G7 current account imbalances: sustainability and adjustment. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Montalvo J (1995) Comparing cointegrating regression estimators: some additional Monte Carlo results. Econ Lett 48:229–234

Stock J, Watson M (1993) A simple estimator of cointegrating vectors in higher order integrated systems. Econometrica 61(4):783–820

Takeuchi F (2011) The exact import price and its implications for the US external imbalance. Appl Econ Lett 18(17):1697–1703

Whelan K (2000) A guide to the use of chain aggregated GDP data. Federal Reserve Board

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I would like to thank the editor and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data Sources and Descriptions

Unless noted, all series are quarterly for the period 1975:1–2011:2

-

Real imports and real GDP in 2005 chain-weighted dollars from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), www.bea.gov

-

Import price indexes and GDP price indexes from BEA

-

Real imports excluding capital goods: capital goods were removed from the series for aggregate goods imports using the Tornqvist approximation following Chinn (2010) and the method outlined in Whelan (2000)

-

Broad CPI-based real exchange rate from the Federal Reserve Board, www.federalreserve.gov

-

Producer price index: quarterly series constructed as the average of the monthly series from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, www.bls.gov

-

Value added-to-exports ratio: quarterly series imputed from the annual series for world trade from Johnson and Noguera (2012), 1975:1–2009:4

-

Import shares (Table 1) calculated from nominal values from BEA

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ceglowski, J. Has Trade Become More Responsive to Income? Assessing the Evidence for US Imports. Open Econ Rev 25, 225–241 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-013-9281-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-013-9281-9