Abstract

In the policy sciences, the intractability of disputes in natural resource governance is commonly explained in terms of a “devil shift” between rival policy coalitions. In a devil shift, policy actors overestimate the power of their opponents and exaggerate the differences between their own and their opponents’ policy beliefs. While the devil shift is widely recognized in policy research, knowledge of its causes and solutions remains limited. Drawing insights from the advocacy coalition framework and social identity theory, we empirically explore beliefs and social identity as two potential drivers of the devil shift. Next, we investigate the potential of collaborative venues to decrease the devil shift over time. These assumptions are tested through statistical analyses of longitudinal survey data targeting actors involved in three policy subsystems within Swedish large carnivore management. Our evidence shows, first, that the devil shift is more pronounced if coalitions are defined by shared beliefs rather than by shared identity. Second, our study shows that participation in collaborative venues does not reduce the devil shift over time. We end by proposing methodological and theoretical steps to advance knowledge of the devil shift in contested policy subsystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Natural resource governance is a policy area where strong stakeholder groups and actor coalitions struggle for power and influence over public policymaking. Basic views of the value and use of resources (e.g., land, water, fish, and wildlife) diverge significantly between stakeholders, and disagreements are difficult to resolve with new knowledge and rational arguments, since rival coalitions interpret information about problems and solutions differently. There is a tendency to “talk past” one another instead of being open to the opposing coalition’s arguments and to productive dialogue. Conflicts over natural resources are therefore often described as complex, wicked, or intractable (Sotirov and Memmler 2012).

The policy science literature, particularly the advocacy coalition framework (ACF) literature, has long recognized that the intractability of some natural resource conflicts is driven by a “devil shift” between rival coalitions (Sabatier et al. 1987). Under the influence of devil shifts, actors misconceive their opponents in two ways: First, they overestimate the power of their opponents and, second, they exaggerate the differences between their own and their opponents’ values and beliefs, questioning their opponents’ motives (Sabatier et al. 1987). Actors in the same coalition are likely to misconceive members of the other coalition and develop a distorted view of the opposing side’s power and motives. The presence of devil shifts hampers the ability to negotiate, find compromises, and take collective action, with potentially negative impacts on policy making in terms of finding solutions seen as legitimate and acceptable by all parties (Fischer et al. 2016; Leach and Sabatier 2005).

A fundamental aspect of democracy is to resolve value conflicts among policy actors and the role of the policy sciences is both to understand these differences as well as to contribute to their solutions (c.f. Lasswell 1971). Advancing knowledge of the devil shift informs this broader objective. Although the devil shift concept is widely recognized in contemporary policy research on advocacy coalitions, it has been subject to limited theoretical elaboration and empirical investigation (Pierce et al. 2017). Recent specifications of the notion of advocacy coalitions, for example, pay little attention to the devil shift concept (Weible et al. 2019; Weible and Ingold 2018). This lack of research into the devil shift is inconsistent with the potential attributed to the phenomenon as a basis for informing a theory of advocacy coalitions within the ACF (Weible et al. 2009). In fact, notions of how and why the devil shift occurs are mostly assumed and not empirically investigated in the wider policy science literature. Some recent exceptions are found in research on policy narratives (Jones and McBeth 2010; Shanahan et al. 2011) exploring both the devil shift and its counterpart angel shift (e.g., Shanahan et al. 2013: Merry 2019; Wolf 2019). These studies have advanced our understanding of the existence and drivers of the devil shift.

Although empirical studies of the occurrence of the devil shift are rare, some previous ACF work does consider the matter (see Leong 2015; Fischer et al. 2016; Sabatier et al. 1987). Sabatier et al.’s (1987) seminal study of US land use policy gave empirical support to the proposition that stakeholders mistrust their opponents’ motives and behavior, while the idea of the misinterpretation of power was only partly supported. Both these assumptions were confirmed in a study of water policy coalitions in Indonesia (Leong 2015). Fischer et al. (2016) not only studied the existence of the devil shift but also specified how it relates to the type of policy process and actor, i.e., taking the step from describing the existence of devils shift to explaining why it occurs. Through a comparative study of nine different policy processes in Switzerland, involving a range of policy actors, they concluded that the phenomenon is more likely to emerge among interest groups and political parties than state actors (Fischer et al. 2016). The present study is inspired by these previous works to explore the factors influencing the devil shift in different contexts. Hereby we seek to extend the research agenda concerning drivers of the devil shift by considering explanatory factors other than actor types and the structural attributes of policy subsystems. Specifically, we investigate two alternative sources of the devil shift: actors’ policy beliefs and group identity.

Prior work identifies some overlap between how the devil shift is depicted in ACF research and how group dynamics are understood in psychological research and social identity theory (SIT) (Tajfel 1974, 1982; see Hornung et al. 2019). Closer integration between the two theoretical strands to further specify the theoretical underpinnings of behavior in policy science has been suggested (cf. Cairney and Weible 2017). Yet, while similarities do exist, the two approaches encompass different ideas about the formation of policy coalitions. Specifically, whereas the ACF assumes that coalition formation is driven by belief similarity (Henry 2011), i.e., actors’ tendency to seek coordination with other actors sharing the same policy beliefs, SIT suggests that actors align in groups, or policy coalitions, due to a sense of a shared group identity, i.e., a “subjective sense of togetherness, we-ness, or belongingness” (Turner 1982, p. 16). In other words, individuals seek coordination with actors with whom they identify in terms of various social categories such as profession, background, and interests. The primary difference between the two theoretical strands can be illustrated by contrasting a sense of belief similarity to a sense of shared group identity when describing the rationale for coalition formation and maintenance. Accordingly, we conceptually contrast belief similarity and social identity as two candidate drivers of the devil shift in conflictual policy areas.

In addition to lack of clarity concerning the drivers of the devil shift, knowledge of how to mitigate or reduce the potential negative effects of the devil shift is limited. The establishment and use of venues for collaboration—sometimes referred to as policy forums (Fischer and Leifeld 2015) where multiple actors, i.e., stakeholders with divergent interests and beliefs, participate and engage in dialogue to reach consensus and agreement on shared goals and solutions—have been suggested as one way to mitigate conflicts between opposing coalitions, specifically in natural resource governance (Carlsson and Berkes 2005; Koebele 2019; Lubell et al. 2009; Reed 2008). However, empirical evidence of the advantages of collaborative governance in general, and of the effects of participation in venues on the presence of the devil shift, in particular, is sparse (Ansell and Gash 2008; Lubell 2004, 2005; Weible et al. 2011). One likely reason for this lack of research is that assessments of collaboration require longitudinal data, which are both costly and challenging to collect. Using a longitudinal research design, this study connects research on policy coalitions with research on collaborative governance (Koebele 2019) to investigate collaborative approaches as means to cope with devil shifts. In addition to examining beliefs and social identity as potential drivers of devil shifts, our study also contributes insights into the prospects of collaborative venues to reduce their incidence over time.

Swedish large carnivore management is an appropriate case-study setting for studying the devil shift and the effects of collaboration. First, prior work has confirmed that this is a policy area that is highly contentious with strong stakeholder groups and rival coalitions holding contrasting beliefs concerning the value of the resources and how they should be managed effectively and fairly (Eriksson 2017; Matti and Sandström 2011, 2013; Sandström and Ericsson 2009). Second, the policy area incorporates several collaborative venues in the form of Wildlife Conservation Committees (WCCs) comprising interest organization representatives and regional politicians (Bill 2000/01:57, 2008/09:210, 2012/13:191). The collaborative system is formalized, the venues are authorized to make decisions, and the system has been in place since 2009. Third, even though the political culture in Sweden has undergone significant changes over the past decades, the country has a long tradition of consultative processes and involvement of concerned interest organizations in public policy making (Nohrstedt and Olofsson 2017). This implies that the prospects for collaborative institutions to mitigate conflicts and decrease the presence of devil shift are particularly favorable in this case.

Large carnivore management in Sweden is the part of wildlife management that focuses on bear, wolverine, lynx, wolf, and golden eagle. The contemporary management system was implemented to improve the low legitimacy of policies regarding these five species (Lundmark and Matti 2015). We collected longitudinal data about perceptions of identity, beliefs, and power among participants in these venues between 2013 and 2017, providing an excellent empirical basis for studying the drivers of the devil shift and examining the potential impacts of collaborative governance.

Drivers of the devil shift in contentious policy issues

The devil shift concept was originally developed within the ACF (Sabatier et al. 1987), which remains one of the most widely applied policy process frameworks (Nohrstedt and Olofsson 2017; Pierce et al. 2017; Weible et al. 2011). The ACF assumes that public policy is developed in policy subsystems, which include actors from various organizations concerned with a policy problem and that actively seek to influence public policy in that domain by translating their beliefs into policy. Some of these actors form advocacy coalitions that tend to be stable over time (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1999; Weible et al. 2019).

Advocacy coalition members include politicians (i.e., political representatives), civil servants, and interest group representatives who coordinate their efforts to gain influence and who share the same set of beliefs about the nature of policy problems and appropriate strategies for addressing them. Adopting the ACF terminology, these “policy core beliefs” (Jenkins-Smith et al. 2014) exist in several forms, ranging from more normative beliefs (e.g., actors’ views of economic development vs. ecological conservation) to understandings of the seriousness of the policy problem (e.g., to what extent large carnivores are or are not under threat), the main causes of the problem (e.g., gene degeneration or hunting), and the appropriate way to solve the problem (e.g., on what administrative level the issue should be managed, by whom and with what policy instruments) (Sabatier 1988; Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1999; see also Matti and Sandström 2011, 2013).Footnote 1 These policy core beliefs constitute the “glue” of coalitions; that is, they foster collaboration among subsystem actors and provide a filter through which actors perceive problems and interpret new information.

The devil shift is based on mechanisms originally elaborated on in social psychology research. The notion of opponents being deemed more powerful than they actually are is explained by a human tendency to value losses more than gains (Tversky and Kahneman 1974, 1991), which leads to the perception of the opposing side always winning and, consequently, being highly powerful. Furthermore, the overestimation of differences in beliefs stems from the fact that it is difficult to combine a positive outlook on oneself (and the coalition one belongs to) with a positive outlook on one’s opponents (see Aronson et al. 2005). The devil shift thus entails misperceptions regarding the rival coalition’s power, beliefs, and motives (Sabatier et al. 1987).

Subsystem actors’ belief systems thereby help reinforce and exaggerate the negative motives, behavior, and influence of their opponents (i.e., members of rival coalitions) in the policy process. Shared beliefs thus constitute a potential driver of the devil shift. On this basis, we hypothesize that:

H1

Coalition members who share similar beliefs and coordinate political behavior exaggerate the power of the opposing coalition’s members.

Hypothesis 1 is firmly grounded in the explanatory logic of the ACF and predicts that the devil shift is likely to be evident among policy actors representing opposing advocacy coalitions based on belief similarity and coordination. Here we measure the presence of the devil shift (H1) by comparing actors’ assessments of their own coalition’s (defined by shared beliefs) power with the assessments of power made by the opposing coalition, and vice versa.

In this study, we contrast beliefs to social identity as an alternative plausible driver of the devil shift. Hornung, Bandelow, and Vogeler (2019) suggest that there are potential benefits in combining SIT with the ACF. They specifically identify similar grounds as well as the potential of SIT to contribute a more elaborated understanding of inter-coalitional relations and, by extension, the devil shift. In brief, SIT (Tajfel 1974, 1982) stresses that individuals cognitively identify themselves in relation to social groups and that these social groups are more important for the individual’s behavior and sense of self than are purely individual psychological processes, such as beliefs. It is thus the group identification, together with intergroup relations, that shape collective action (Turner 1982). The cognitive basis of this dynamic is established in four steps. Accordingly, the world is (1) categorized in social groups that provide a locus for (2) identification. Belonging to and identifying with a social group, the in-group, provides a basis for (3) social comparisons with other groups, i.e., the out-groups. These conditions result in a wish among actors to (4) distinguish the in-group from the out-group, which also enhances the self-esteem of group members (Brown and Ross 1982).

Social categorization into in- and out-groups leads to certain biases that affect perception and action. In-group bias means that self-esteem will only be enhanced if group members view the in-group as superior to other groups, which has the implication of treating out-group members unfairly. Out-group homogeneity is when in-group members view out-group members as more similar and homogenous than they really are fueling the perception that they are all alike (Aronson et al. 2005).

The in-group and out-group biases in SIT resemble the phenomenon described as the devil shift in ACF, i.e., the exaggeration of differences and power between opponents (cf. Sabatier et al. 1987). Categorization, identification, and the need to maintain a positive outlook on oneself and one’s group, in relation to the opposing group, could explain how and why the devil shift occurs. At the same time, the two frameworks are based on different assumptions concerning the basic constitution and attributes of coalitions. The ACF defines belief similarity as the primary driver of coordination, whereas SIT emphasizes shared group identity as the key to coalition formation. Thus, the two foundations for coalition–formation are distinct. However, whereas coalitions (as defined by the ACF) form based on shared beliefs among policy actors, those actors may develop a shared identity through time. Conversely, it is possible, in theory, that the gradual development of a shared identity among coalition members may also lead to greater belief consistency. In light of these arguments, we draw on SIT to elaborate and test an alternative hypothesis about the devil shift as driven by social group identification, here assessed by identification with the key interest groups in large carnivore management:

H2

Coalition members who share a social identity and coordinate political behavior exaggerate the power of the opposing coalition’s members.

The presence of a devil shift (H2) is measured by comparing actors’ assessments of the power of their own and opposing coalitions (defined by shared group identify) with the similar power assessments made by the opposing coalition.

Devil shift in collaborative governance

The presence of the devil shift solidifies coalition boundaries, complicates communication across coalitions, obstructs negotiations, and prevents cross-coalitional learning (Leach and Sabatier 2005). Therefore, the issue of how to mitigate these biased perceptions has been acknowledged in research concerning different types of management systems.

Empirical work has been undertaken to understand how participation in collaborative venues influences perceptions of other stakeholders in policymaking, including regarding attributes associated with power and effectiveness (Lubell et al. 2017; Mewhirter et al. 2019; Sabatier et al. 2005). By definition, these venues constitute collaborative institutions that provide “inclusive decision processes that bring together multiple stakeholders, help build networks and trust, and emphasize consensus decision procedures and voluntary compliance” (Henry et al. 2010, p. 288). In theory, these venues offer a potential solution to collective-action problems as they may help reduce transaction costs that prevent actors from overcoming differences and formulating and committing to mutually beneficial policies (cf. Carlsson and Berkes 2005). In turn, these institutions may also mitigate conflict by reducing the devil shift.

Several studies have hypothesized that the institutional setup of the policy subsystem—regarding the presence and exploitation of formalized and authorized collaborative venues, especially if the system has been in place for some time—is likely to influence the conditions for cross-coalitional learning (cf. Koebele 2019). Weible et al. (2011) and Lubell (2005) specifically address how the presence of collaborative forums affects the occurrence of the devil shift. Both studies examine the role of collaborative institutional settings in mitigating the effects of the devil shift or reducing the devil shift over time. Inspired by these works, we formulate the following hypothesis concerning the capacity of institutionalized collaboration to reduce devil shifts:

H3

Policy subsystems incorporating institutionalized venues for collaboration will experience a reduction in the devil shift over time.

In theory, hypothesis 3 points to the importance of repeated interactions and deliberations among opponents over time as a means of overcoming mutual misperceptions concerning trustworthiness, evil, and power. Hence, collaborative venues are assumed to counteract any tendency of beliefs (H1) or identity (H2) to reinforce the devil shift. We recognize here that the ACF acknowledges not only the presence of collaborative venues but also that the specific nature of those venues is important in shaping learning across belief systems. Specifically, Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1993) hypothesized that productive analytical debate across coalitions—and by extension a potential reduction in the devil shift—is more likely if the forum is (1) prestigious enough to motivate actors from different coalitions to participate and (2) dominated by professional norms (i.e., commitment to scientific norms based on shared theoretical and empirical presuppositions). Here, however, we are interested in the more basic question of whether the presence of an institutionalized collaborative forum with formal decision-making authority has any impact on the devil shift over time regardless of its more specific attributes. However, we note that, in the studied case, the collaborative venues fulfill at least the first criterion, i.e., the forum is prestigious enough to motivate participation, given its prominent position in the subsystem. However, we have no information about the second criterion regarding the norms guiding the interactions within these venues.

Methods

The case of large carnivore management

The present governance system for large carnivores in Sweden was introduced in 2009 based on the government’s desire to increase the legitimacy of carnivore policy and management practices through increased stakeholder participation and collaboration (Bill 2000/01:57, 2008/09:210, 2009:1474, 2012/13:191). It is a multi-level governance system in which authority over goals, objectives, and measures is divided between administrative levels, i.e., from the EU, via national and meta-regional levels, to the regional level, and between political forums, public authorities, and collaborative venues.

At the regional level, the governance system consists of 21 Wildlife Conservation Committees (WCCs), each with 14–16 committee members, organized under the county administrative boards and chaired by the county governor. The WCCs represent interest-based collaborative venues and should, according to the regulation, include representation of the following interests: forestry, nature conservation, agriculture, hunting/wildlife management, recreation/outdoor life, tourism/local business, traffic safety, and law enforcement. In some regions, representation of commercial fisheries, seasonal foraging, reindeer herding, and the Sámi Parliament is also obligatory. In addition, the county councils nominate political party representatives to the committees. All committee members are nominated by the concerned organizations but formally appointed by the county administrative board (Bill 2009:1474).

The mandate of the WCCs is formalized and concerns issues related to hunting arrangements and economic compensation (Regulation 2009:1474; SFS 2001:724). The WCCs also take part in the process of setting minimum levels and developing regional management plans (SOU 2012:22). Suggestions concerning regional flourishing levels must, however, coincide with national reference levels, and the final decisions are made by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Regulation 2009:1263). Furthermore, the regional management plans, developed and approved by WCCs, have to be aligned with national management plans (Bill 2012/13:191; Regulation 2009:1263, 2009:1474). The influence of WCCs on large carnivore management is thus conditioned by national-level authorities.

The WCCs are further organized into three larger management areas (i.e., north, central, and south) to enable a comprehensive overview of wildlife populations. Coordination councils, which include county governors in each management area, ensure coordination on important matters at this meta-regional level (Bill 2008/09:210). Since the three areas diverge in terms of contextual factors and specific policy problems, with likely impact on actor behavior and coordination patterns (cf. Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1999), they are considered here as separate policy subsystems.

Descriptive and statistical analysis of survey data

Data were collected via two surveys targeting WCC members, one administered in 2013 and the other in 2017. The surveys were sent to all ordinary members of the WCCs (about 305 individuals) and the combined response rate was 62 percent in 2013 and 71 percent in 2017. The survey covered all of Sweden’s 21 regions. These 21 regions are organized into three large carnivore management areas (SFS 2009:1263): the northern management area (including the regions of Jämtland, Västernorrland, Västerbotten, and Norrbotten), the central management area (including the regions of Stockholm, Uppsala, VästraGötaland, Värmland, Örebro, Västmanland, Dalarna, and Gävleborg), and the southern management area (including the regions of Södermanland, Östergötland, Jönköping, Kronoberg, Kalmar, Gotland, Blekinge, Skåne, and Halland). Since each management area is considered here as a separate policy subsystem, members of all WCCs included in each area will be analyzed collectively for both 2013 and 2017, i.e., each subsystem is analyzed as the aggregate of its individual WCCs.

Exploring coalitions based on belief similarity and social identity

In this study, the presence of devil shift is empirically measured by analyzing survey questions constructed to map coalitions and perceptions of power. The WCC members were presented with a list of interests and asked questions about: (a) which general interest they see as the most powerful influencer of large carnivore policies in Sweden; (b) which interests are aligned with their views of large carnivore policies; (c) which interests they seek to collaborate with regarding large carnivore policies; and (d) which interest they most identify with, aside from the interest they represent themselves. The respondents marked an “x” for yes, while an empty space indicated “no” in the survey. For this analysis, we coded responses into dummy variables for each question and each interest, with 1 for “yes” and 0 for “no.”

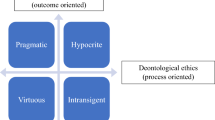

The method for defining coalitions is depicted in Fig. 1. First, coalitions of the two rival interests in Swedish large carnivore policy—i.e., hunting and nature conservation (cf. Matti and Sandström 2011, 2013)—were created by including respondents who either represented the specific interest (hunting or nature conservation) or responded that they both have a similar view and collaborate with the specific interest (shared beliefs and coordination following the ACF, configurations A + B in Fig. 1). Our way of defining coalitions, as including representatives of different interests, diverges slightly from how coalitions are commonly defined in the ACF literature, as based on measures of coordination and beliefs only. The reasons for doing so are related to, first, the interest-based design of the collaborative venues that are the focus of empirical investigation, with WCC members being nominated as representatives, and, second, to the design of survey questions, asking the WCC members about which interest (aside from the one they represent) they most identify with. Accordingly, the hunting coalitions within each of the three subsystems consist of respondents representing hunting in WCCs and of respondents sharing beliefs and collaborating with the hunting interest.

Representation of the methodological approach for identifying coalitions and the devil shift over time (t1–2). Subsystems modeled based on the ACF (upper right) include actors expressing shared beliefs (i.e., expression of similar views) with either the hunting or nature conservation interest in combination with collaboration with an interest (configuration A), and actors representing either interest (configuration B). Subsystems modeled based on SIT (lower right) include actors expressing identification with either the hunting or nature conservation interest in combination with collaboration with an interest (configuration C), and actors representing either interest (configuration B). Hypothesis testing (H1–3) is carried out by comparing how actors in the two coalitions view the power of the members of the other coalition and by contrasting the results across the two coalition structures (ACF and SIT, respectively)

In addition, following SIT, another set of coalitions was constructed using the same logic, but instead of similar views, we focused on responses regarding which interest the respondents identify the most with (along with coordination, configurations C + B in Fig. 1). For example, the nature conservation coalitions in the three subsystems were created by including respondents representing nature conservation as well as respondents identifying the most with and collaborating with the nature conservation interest (i.e., identification and coordination).

The two measures used to measure coalition membership, based similar views and social identity, correlate to a value of 0.77 (Pearson’s correlation = 0.77 on average for all systems, p < 0.05). This means that while the two measures are related they do capture different empirical aspects. Using these measures, we obtain different, though slightly overlapping, patterns of coalition membership.

The survey explicitly asked respondents to indicate their perceptions of general interests instead of their perceptions of specificactors representing any given interest. However, there is a clear link between interests and actors that enables the analysis of coalitions in this study. The seats in the WCCs are directly connected to specific interests, or political parties, so we find it reasonable to assume that it was well known among WCC members which actor represented which interest.

Exploring the presence of devil shift

After constructing the coalitions for each subsystem and time period, devil shift presence was measured using the Chi square test (see Hair et al. 1998) for each of the three subsystems and for 2013 and 2017, respectively. Here we used survey responses regarding how powerful the coalition respondents perceived themselves and the opposing interest coalition to be. Only one of the two attributes of devil shifts is measured in this study, i.e., the “evilness” of opponents is omitted. By definition, differences in responses concerning perceived power, depending on coalition belonging, indicate devil shifts. These analyses were also performed for coalitions based on social identity. The strength of each approach, as a devil shift predictor, was examined by comparing the Chi square values, with larger values indicating a stronger devil shift.

Exploring possible changes in the devil shift

Changes in the devil shift over time are calculated using McNemar’s test. This analysis was performed using the results of the approach (i.e., similar beliefs or social identity) that had the highest Chi square values and was therefore a better indicator of the presence of devil shifts.

The data used for these tests were the respondents’ perceptions of the opposing coalitions’ power (see survey question concerning the most powerful influencer of large carnivore policies in Sweden) in 2013 and in 2017, respectively, divided by coalition belonging (i.e., hunting vs. nature conservation), for each of the three subsystems (i.e., north, central, and south). The test thus examined how powerful the hunting coalition respondents perceived the nature conservation coalition to be in 2013 and 2017, and how powerful the nature conservation coalition respondents perceived the hunting coalition to be in 2013 and 2017. This testing was performed for each subsystem, resulting in a total of three tests.

Results

The presence of a devil shift in Swedish large carnivore management

Actor composition for the hunting and nature conservation coalitions

Table 1 presents the actor composition for the hunting and nature conservation coalitions (based on shared beliefs) in 2013 and 2017. Here we can see that the hunting coalitions were populated by respondents representing several interests with political, hunting, agriculture and forestry representatives being prominent. The nature conservation coalitions included respondents representing mainly three interests: political, nature conservation and outdoor recreation.

Perceptions on the most power influencers of carnivore policies

Table 2 presents who the two coalitions (based on shared beliefs) perceived to be the most powerful influencer of carnivore policies in 2013 and 2017, for all three subsystems. In 2013, a large majority of the hunting coalition respondents, in each of the three subsystems, saw nature conservation as most powerful. The nature conservation coalition respondents perceived hunting, followed by reindeer herding, as the most powerful interests. In 2017, the results were largely the same, but with one significant difference. By that time, many respondents in both coalitions, and in all three subsystems, identified government agencies as one of the most powerful influencers of carnivore policies, which is a drastic change compared to 2013.

Assessing the devil shift based on beliefs versus identity

The results of variance analyses of each subsystem in 2013 (Table 3) indicate a difference in how the coalitions perceive their own and the opposing coalition’s power. Each coalition consistently perceives its own power to be lower than that of the opposing coalition, and this finding is significant across all three subsystems. The results remain robust (i.e., there are persistent significant differences in how the coalitions perceive their own and the opposing coalition’s power) when constructing the coalitions based on social identification rather than shared beliefs, though the Chi square values are lower in four of the six cases. This means that the construction of coalitions based on a combination of similar views (as a measure of shared beliefs) and coordination (configuration A + B, Fig. 1) results in a larger devil shift in four of the six cases, compared with coalition construction based on identity measures (configuration C + B, Fig. 1).

Results for 2017 are largely the same as for 2013 (Table 3). The results still indicate a significant difference in how the coalitions perceive their own and the opposing coalitions’ power for all three subsystems. When constructing coalitions based on social identification rather than shared beliefs, the results remain robust. The Chi square values are higher in three of the six cases than when constructing coalitions based on shared beliefs. This means that both ways of constructing coalitions resulted in a larger devil shift in three of the six cases.

Changes in the presence of a devil shift over time

Since constructing coalitions based on shared beliefs resulted in higher Chi square values in general (with higher values in seven of 12 tests, Table 3), we used these results to assess the devil shift and possible changes in it over time. For all subsystems, the result of McNamar’s test indicated no significant differenceFootnote 2 in the hunting coalition’s perception of the nature conservation coalition’s power between 2013 and 2017. The same can be said of the nature conservation coalition’s view of the hunting coalition’s power at the two time points, for each subsystem. Thus, no significant changes in perceptions of the other side, over time, were found for any of the six coalitions included in the analysis.

Conclusion

In this work, we found, first, empirical evidence that the devil shift is more pronounced between opposing coalitions when they are defined by shared beliefs rather than shared identity. We consider this finding empirically robust, as it derives from a comparative assessment of three policy subsystems in Swedish large carnivore policy in two time periods.

The empirical results support the hypothesis (H1) based on the advocacy coalition framework (ACF), which predicts that coalition members who share similar beliefs and coordinate political behavior will exaggerate the power of the opposing coalition’s members. The second hypothesis (H2), building on social identity theory (SIT), predicting that coalition members who share a social identity and coordinate political behavior will exaggerate the power of the opposing coalition’s members, was not rejected but received less empirical support compared with H1.

By empirically investigating beliefs and identity as separate drivers of the devil shift, the objective of this study was to extend previous work on the devil shift that focused exclusively on structural factors and actor types as potential explanations (Fischer et al. 2016). Our work adds the important finding that the devil shift is also driven by the sociopsychological mechanisms that underpin advocacy coalitions. The results suggest that shared beliefs are a stronger predictor than is shared identity of the tendency of policy actors to exaggerate the power of their opponents, though our study does not specify why this would be the case. Further work is therefore encouraged to delve deeper into the underlying drivers and mechanisms of devil shifts.

Our second finding is that, contrary to the assumption advanced in collaborative governance research, participation in collaborative venues did not reduce the devil shift over time. Again, we consider this finding empirically robust as it holds for policy actors in two different coalitions across three policy subsystems. The results indicate that between 2013 and 2017, there were no changes in how the opponents within Swedish carnivore policy viewed each other in terms of power. Thus, we find no empirical support for the hypothesis (H3) that policy subsystems with institutionalized venues for collaboration will experience a reduction in the devil shift over time.

From this perspective, our results suggest that participation in the WCCs, as examples of institutionalized collaborative venues with formal decision-making authority, did not reduce actors’ exaggeration of the power of their opponents. This result is somewhat unexpected, as the investigated venues have at least one characteristic assumed to enhance cross-coalitional learning, i.e., being prestigious enough to attract concerned interest representation (cf. Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1993), and are situated within a consensus-based national context (Nohrstedt and Olofsson 2017). Again, our data do not allow us to explain why this was the case, though we speculate that this has at least three explanations. First, it might be that shared beliefs are so deeply rooted among policy actors that these beliefs are maintained despite repeated interactions with opponents in collaborative venues. Nevertheless, previous case studies of some of the WCCs included here have indicated small modifications in policy core beliefs (Lundmark et al. 2018) as well as signs of learning among committee members (Sandström and Lundmark 2016). Second, there may be something about the context, the institutional rules guiding interactions, and/or the process of the investigated collaborative venues that prevent them from reducing the devil shift over time. For instance, one common explanation holds that regular interactions will gradually build trust among actors, which in theory would reduce misperceptions and misrepresentations of other actors through time. One plausible scenario here is that the collaborative process did not enable trust-building activities but rather focused on other objectives or activities. A third explanation is methodological; that the five-year timeframe selected for this analysis was simply too short for changes in devil shift to take place. Time is critical for building trust and enabling constructive communication in collaborative settings (Lubell et al. 2009). Future studies of devil shift in various contexts, i.e., different countries, policy subsystems, and collaborative arrangements, are strongly encouraged to empirically examine these potential explanations.

This study contributes to the ACF literature on advocacy coalitions by enhancing our theoretical understanding of the drivers of the devil shift (see Fischer et al. 2016) and of the effects of collaborative governance arrangements in mitigating conflict in policy subsystems (see Koebele 2019; Lubell 2005; Weible et al. 2011). In addition, we also make methodological and empirical contributions. The study has elaborated a study design for advancing the understanding, identification, measurement, and analysis of the devil shift using longitudinal survey data. Although these data enabled us to empirically study devil shift across subsystems, several caveats apply. Since the data were analyzed at the subsystem level, the number of observations was small in some cases. This increases the risk of not rejecting the null hypothesis even if it is not true (i.e., Type II error, see Hair et al. 1998), so larger sample sizes are encouraged in future studies. In addition, a mixed method design, combining survey responses from a larger set of subsystem actors with interviews and/or document analysis, could enable a more detailed examination of the devil shift and its drivers.

Finally, the results provide empirically informed insights into conflicts and governance capacity in Swedish large carnivore management. The results of this work are both expected and unexpected in this context. While devil shifts among rival coalitions were anticipated, the absence of variation across policy subsystems is somewhat surprising since the presence of large carnivores, and related conflicts, differ between the three management areas (i.e., south, central, and north) (SEPA 2018). Moreover, as discussed above, the stability of the devil shift over time was not anticipated given the alleged importance of collaborative institutions. Both findings may be at least partially explained by the fact that large carnivore policy is still a highly centralized issue that might still be perceived as a national concern by involved policy actors. Although the institutional change reallocated power to regional collaboration venues (i.e., Wildlife Conservation Committees, WCCs), the overall institutional framework as well as the overall goals and rules establishing the conditions for regional wildlife management are nevertheless decided by national authorities (see “Methods”). Considering the national level as the primary policy level, with implications for coalition formation, the similarities across subsystems are less surprising. Furthermore, the centralized character of the system not only explains the increase in actors’ perceptions of government actors as the most powerful ones, but also the system’s inability to reduce devil shift between opposing coalitions. This interpretation of the results is partly supported by previous findings regarding the WCCs, that their members’ expectations, prior to their engagement, regarding their potential to influence policy were not met (Lundmark and Matti 2015; Nilsson 2018). Mandate and perceived influence over policymaking are important conditions for deliberative processes and cross-coalitional learning to evolve (cf. Koebele 2019), and in the case of WCCs this mandate is likely perceived as limited.

Keeping in mind the potentially destructive consequences of devil shifts in policymaking and management, improved knowledge of the phenomenon and how it can be mitigated in different contexts and institutional designs is needed in order to create more effective, legitimate, and sustainable governance systems and policies. Efforts to empirically examine the devil shift across contexts also have potential to inform theory of the evolution and mitigation of conflicts in contested policy subsystems. We hope that this work will inspire further studies to specify how the devil shift plays out and can be mitigated, in different contexts.

Notes

The ACF assumes that policy core beliefs are based on a deeper layer of more robust deep-core beliefs (Jenkins-Smith et al. 2014) and that policy core beliefs are further translated into more concrete, specific strategies and measures called secondary aspects (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith 1999; Weible and Sabatier 2009).

For the northern carnivore management area, the changes were so small over time that a McNemar’s test could not even be performed.

References

Ansell, C., & Gash, A. (2008). Collaborative governance in theory and practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(4), 543–571.

Aronson, E., Wilson, T. D., & Akert, A. M. (2005). Social psychology (5th ed.). New York: Prentice Hall.

Bill 2000/01:57. Sammanhållen rovdjurspolitik. Swedish Government.

Bill 2008/09:210. Ennyrovdjursförvaltning. Swedish Government.

Bill 2009:1474. Förordning om viltförvaltningsdelegationer. Swedish Government.

Bill 2012/13:191. En hållbar rovdjurspolitik. Swedish Government.

Brown, R. J., & Ross, G. F. (1982). The battle for acceptance: An investigation into the dynamics of intergroup behavior. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Social identity and intergroup relations (pp. 155–178). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cairney, P., & Weible, C. M. (2017). The new policy sciences: Combining the cognitive science of choice, multiple theories of context, and basic and applied analysis. Policy Sciences, 50(4), 619–627.

Carlsson, L., & Berkes, F. (2005). Co-management: Concepts and methodological implications. Journal of Environmental Management, 75, 65–76.

Eriksson, M. (2017). Changing attitudes to Swedish wolf policy: wolf return, rural areas, and political alienation. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Political Science, Umeå University, Sweden.

Fischer, M., Ingold, K., Sciarini, P., & Varone, F. (2016). Dealing with bad guys: Actor- and process-level determinants of the “devil shift” in policy making. Journal of Public Policy, 36(2), 309–334.

Fischer, M., & Leifeld, P. (2015). Policy forums: Why do they exist and what are they used for? Policy Sciences, 48(3), 363–382.

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). London, UK: Prentice Hall International.

Henry, A. D. (2011). Ideology, power, and the structure of policy networks. Policy Studies Journal, 39, 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00413.x.

Henry, A. D., Lubell, M., & McCoy, M. (2010). Belief systems and social capital as drivers of policy network structure: The case of California regional planning. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(3), 419–444.

Hornung, J., Bandelow, N. C., & Vogeler, C. S. (2019). Social identities in the policy process. Policy Sciences, 52(2), 211–231.

Jenkins-Smith, H. C., Nohrstedt, D., Weible, C. M., & Sabatier, P. A. (2014). The advocacy coalition framework: Foundations, evolution, and ongoing research. Theories of the Policy Process, 3, 183–224.

Jones, M. D., & McBeth, M. K. (2010). A narrative policy framework: Clear enough to be wrong? Policy Studies Journal, 38(2), 329–353.

Koebele, E. A. (2019). Integrating collaborative governance theory with the advocacy coalition framework. Journal of Public Policy, 39(1), 35–64.

Lasswell, H. D. (1971). A pre-view of policy sciences. Policy Sciences book series. New York: Elsevier.

Leach, W. D., & Sabatier, P. A. (2005). To trust an adversary: Integrating rational and psychological models of collaborative policymaking. American Political Science Review, 99(4), 491–503.

Leong, C. (2015). Persistently biased: The devil shift in water privatization in Jakarta. Review of Policy Research, 32(5), 600–621.

Lubell, M. (2004). Collaborative environmental institutions: All talk and no action? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 23(3), 549–573.

Lubell, M. (2005). Do watershed partnerships enhance beliefs conducive to collective action. In P. A. Sabatier, W. Focht, M. Lubell, Z. Trachtenberg, A. Vedlitz, & M. Matlock (Eds.), Swimming upstream: Collaborative approaches to watershed management (pp. 201–232). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Lubell, M., Leach, W. D., & Sabatier, P. A. (2009). Collaborative watershed partnerships in the epoch of sustainability. In D. A. Mazmanian & M. E. Kraft (Eds.), Toward sustainable communities: Transitions and transformations in environmental policy (pp. 255–288). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lubell, M., Mewhirter, J. M., Berardo, R., & Scholz, J. T. (2017). Transaction costs and the perceived effectiveness of complex institutional systems. Public Administration Review, 77(5), 668–680.

Lundmark, C., & Matti, S. (2015). Exploring the prospects for deliberative practices as a conflict-reducing and legitimacy-enhancing tool: The case of Swedish carnivore management. Wildlife Biology, 21(3), 147–156.

Lundmark, C., Matti, S., & Sandström, A. (2018). The transforming capacity of collaborative institutions: Belief change and coalition reformation in conflicted wildlife management. Journal of Environmental Management, 226, 226–240.

Matti, S., & Sandström, A. (2011). The rationale determining advocacy coalitions: Examining coordination networks and corresponding beliefs. Policy Studies Journal, 39(3), 385–410.

Matti, S., & Sandström, A. (2013). The defining elements of advocacy coalitions: Continuing the search for explanations to coordination and coalition structure. Review of Policy Research, 30(2), 240–257.

Merry, M. K. (2019). Angels versus devils: The portrayal of characters in the gun policy debate. Policy Studies Journal, 47(4), 882–904.

Mewhirter, J., Coleman, E. A., & Berardo, R. (2019). Participation and political influence in complex governance systems. Policy Studies Journal, 47(4), 1002–1025.

Nilsson, J. (2018). What Logics Drive the Decision-Making of Public Officials? Doctoral Disseration. Luleå: Luleå University of Technology.

Nohrstedt, D., & Olofsson, K. (2017). A review of applications of the advocacy coalition framework in Swedish policy processes. European Policy Analysis, 2(2), 18–42.

Pierce, J. J., Peterson, H. L., Jones, M. D., Garrard, S. P., & Vu, T. (2017). There and back again: A tale of the advocacy coalition framework. Policy Studies Journal, 45(S1), S13–S46.

Reed, M. S. (2008). Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation, 141(10), 2417–2431.

Regulation 2009:1263. Om förvaltning av björn, varg, järv, lo och kungsörn. Näringslivsdepartementet RSL.

Regulation 2009:1474. Om viltförvaltningsdelegationer. Miljö- och energidepartementet.

Sabatier, P. A. (1988). An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sciences, 21, 129–168.

Sabatier, P. A., Focht, W., Lubell, M., Trachtenberg, Z., Vedlitz, A., & Matlock, M. (Eds.). (2005). Swimming upstream: Collaborative approaches to watershed management. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sabatier, P. A., Hunter, S., & McLaughlin, S. (1987). The devil shift: Perceptions and misperceptions of opponents. Western Political Quarterly, 40, 449–476.

Sabatier, P. A., & Jenkins-Smith, H. C. (1993). Policy change and learning: An advocacy coalition approach. Boulder: Westview Press.

Sabatier, P. A., & Jenkins-Smith, H. C. (1999). The advocacy coalition framework: An assessment. In P. A. Sabatier (Ed.), Theoriesof the Policy process boulder (pp. 117–166). Boulder: Westview Press.

Sandström, C., & Eriksson, G. (2009). Om svenskars inställning till rovdjursfrågor. Rapport 2009:2. Umeå: Umeå universitet (in Swedish).

Sandström, A., & Lundmark, C. (2016). Network structure and perceived legitimacy in wildlife collaborative management. Review of Policy Research, 33(4), 442–462.

SEPA (2018) Rovdjuren i Sverige [Carnivores in Sweden]. Website. Retrieved October 30, 2018 from https://www.naturvardsverket.se/Sa-mar-miljon/Vaxter-och-djur/Rovdjur/.

SFS 2001:724. Viltskadeförordning. Swedish Ministry of Enterprise.

SFS 2009:1263. Förordning om förvaltning av björn, varg, järv, lo och kungsörn.Swedish Ministry of Enterprise.

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D., McBeth, M. K., & Lane, R. R. (2011). Policy narratives and policy processes. Policy Studies Journal, 39(3), 535–561.

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D., McBeth, M. K., & Lane, R. R. (2013). An angel on the wind: How heroic policy narratives shape policy realities. Policy Studies Journal, 41(3), 453–483.

Sotirov, M., & Memmler, M. (2012). The advocacy coalition framework in natural resource policy studies—Recent experiences and further prospects. Forest policy and economics, 16, 51–64.

SOU 2012:22. Mål för Rovdjuren. Swedish Ministry of the Environment.

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Information (International Social Science Council), 13(2), 65–93.

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social Identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Turner, J. C. (1982). Towards a cognitive redefinition of the social group. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Social identity and intergroup relations (pp. 15–40). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. science, 185(4157), 1124–1131.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference-dependent model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 1039–1061.

Weible, C. M., & Ingold, K. (2018). Why advocacy coalitions matter and practical insights about them. Policy & Politics, 46(2), 325–343.

Weible, C. M., Ingold, K., Nohrstedt, D., Henry, A. D., & Jenkins-Smith, H.-C. (2019). Sharpening advocacy coalitions. Policy Studies Journal,. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12360.

Weible, C. M., & Sabatier, P. A. (2009). Coalitions, science, and belief change: Comparing adversarial and collaborative policy subsystems. Policy Studies Journal, 37(2), 195–212.

Weible, C. M., Sabatier, P. A., Jenkins-Smith, H. C., Nohrstedt, D., Henry, A. D., & DeLeon, P. (2011). A quarter century of the advocacy coalition framework: Introduction to the special issue. Policy Studies Journal, 39, 349–360.

Weible, C. M., Sabatier, P. A., & McQueen, K. (2009). Themes and variations: Taking stock of the advocacy coalition framework. Policy Studies Journal, 37(1), 121–140.

Wolf, E. E. A. (2019). Dismissing the “vocal minority”: How policy conflict escalates when policymakers label resisting citizens. Policy Studies Journal. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12370.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Lulea University of Technology. This study is based on data collected through projects funded by Viltvårdsfonden, the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Grant No. NV-01337-15), and the Swedish research council FORMAS (Grant Nos. 2015-00996, 254-2014-586 and 2011-1363).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nilsson, J., Sandström, A. & Nohrstedt, D. Beliefs, social identity, and the view of opponents in Swedish carnivore management policy. Policy Sci 53, 453–472 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-020-09380-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-020-09380-5