Abstract

Evaluations are a potentially important tool for democratic governments: they provide a basis for accountability and policy learning. To contribute to these key functions, evaluations must be of sufficient methodological quality. However, this quality is threatened by both political influences and technical complexities. This article describes and explains the variance in the quality of ex-post legislative (EPL) evaluations conducted by the European Commission, which is a frontrunner in this realm. A number of potential political and technical explanations of evaluation quality are tested with a unique, self-constructed dataset of 153 EPL evaluations. The results show that the Commission’s EPL evaluations usually apply a robust methodology, while the clarity of their scope, the accuracy of their data and the foundations of their conclusions are problematic. The variance in this quality is mainly explained by the type of evaluator: EPL evaluations conducted by external actors are of higher quality than evaluations conducted internally by the Commission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Theoretically, evaluations fulfil two important functions in democratic political systems. Firstly, by providing information on the merit of government interventions, they enhance accountability to political principals (ultimately, the voters), which want to ascertain to what extent their agents managed to solve societal problems (Vedung 1997: 102–107). Secondly, evaluations can contribute to policy improvement. They provide a knowledge base for learning processes, particularly regarding how policies can be delivered as efficiently as possible (Mousmouti 2012: 198–199; Sanderson 2002: 3; Van Aeken 2011: 45; Vedung 1997: 102–111).

However, this twofold contribution of evaluations hinges on a key necessary condition: evaluation quality (Forss and Carlsson 1997: 481). Evaluative information only enhances accountability and learning if it is accurate and clear. When actors try to learn what policies work based on evaluations containing misleading data, the decisions that they make are unsubstantiated, which may lead to poor decision-making (Cooksy and Caracelli 2005: 31; Mayne and Schwartz 2005: 7; Sanderson 2002: 13). Furthermore, since evaluations claim to describe reality objectively, their credibility is thwarted if actors find out that they contain misleading information. When this happens, political principals are likely to distrust further evaluations, which damages accountability relations and reduces the potential for learning (Cooksy and Caracelli 2005: 31; Mayne and Schwartz 2005: 7).

Evaluation quality can be compromised by two sets of factors. A first potential threat is political influence. Because public policies are inherently value-related (Daviter 2015: 495), policy evaluations can be used strategically in the political arena (Vedung 1997: 111–113): they can become ‘ammunition in political battles’ (Schoenefeld and Jordan 2019: 377). For example, they may serve to shift blame between actors and to legitimize or criticize policies (Bovens et al. 2008: 319; Schoenefeld and Jordan 2019: 372; Weiss 1993: 94).

One way to deal with politically unwelcome evaluations is to not initiate them when negative outcomes are likely (Van Voorst and Mastenbroek 2017: 645). However, in some situations this may be impossible, for example because evaluation is made compulsory by legal requirements. When an evaluation with potentially negative outcomes must be conducted, governments have an incentive to manipulate their content, for example by selecting evaluation questions and methods that make convenient outcomes more likely (Chelimsky 2008: 404; House 2008: 418). In such cases, evaluation quality is compromised.

Secondly, evaluation quality may be thwarted by ‘technical’ factors, inherent to the methodological difficulties of evaluating public policies. A first technical explanation is evaluation capacity: organizations that have more/better resources and procedures in place regarding evaluations may be able to produce better reports, as such capacity allows for extra investments in every phase of the evaluation process (Forss and Carlsson 1997: 498; Nielsen et al. 2011: 325–327; Rossi et al. 2004: 414). The type of evaluator could also matter: external parties may produce better evaluations than internal ones, given the fact that they have more expertise (Vedung 1997: 117). A third technical explanation is complexity: for some policies it is more difficult to produce a high-quality evaluation than for others (Bussmann 2010: 281).

In sum, evaluation quality is important from the vantage point of democracy, but is threatened by political and technical factors. Despite this assertion, so far the policy literature has produced little large-scale empirical research on the quality of policy evaluations, and none on its antecedents. This study seeks to fill this gap in the literature. It does so for a single case: the European Union’s (EU’s) ex-post legislative (EPL) evaluations.

There are four reasons to select this case. First, the EU is considered a frontrunner in the field of legislative evaluation (OECD 2015: 30, 158–159). Second, the European Commission, which is the main executive institution of the EU and which therefore bears the primary responsibility for its policy evaluations, is a comparatively technocratic institution. This means it is relatively insulated from party politics and parliamentary control.Footnote 1 Third, the EPL evaluations conducted by the Commission (2015: 282–288) are tied to a firm set of quality criteria. Together, these three reasons make the EU’s EPL evaluations a most likely case to find high evaluation quality. This makes it suitable for a first large-scale explanatory study about the topic: if high evaluation quality cannot be found here, it is even less likely to be found elsewhere. The fourth reason to study this case is pragmatic: it has been proven possible to systematically collect evaluations published by the Commission (Mastenbroek et al. 2016), which stands in stark contrast to the difficulties in unearthing evaluations in other systems.

To summarize, this article aims to answer the following research question: how can the variance in the quality of the European Commission’s ex-post legislative evaluations be explained? This question is answered with the help of a unique, self-constructed dataset of 153 EPL evaluations conducted or outsourced by the Commission during 2000–2014. The results show that the Commission’s EPL evaluations do well in terms of applying a robust methodology, but that the clarity of their scope, the accuracy of their data and the foundations of their conclusions are problematic. The variance in this quality is mainly explained by the type of evaluator: EPL evaluations conducted by external actors are of higher quality than evaluations conducted internally by the Commission.

The main relevance of this study is that it advances our knowledge of evaluation quality and helps us to uncover the weight of political and technical influence on it. In addition, this study enhances our knowledge of the European Commission as a frontrunner in the realm of evaluation. Despite the theoretical importance of the topic, empirical research about the quality of the Commission’s EPL evaluations has so far been limited. An earlier descriptive study of the Commission’s whole system for EPL evaluations (Mastenbroek et al. 2016: 1340) and the reports from the RSB (2018: 11) and the European Court of Auditors (2018) showed the quality of the Commission’s EPL evaluations varies considerably, but a detailed, explanatory and (relatively) up-to-date academic analysis of this topic was lacking up until this point.

The case of the EU

The European Union (EU) is frequently called a ‘regulatory state’ because of its reliance on legislation as its main policy instrument (Majone 1999: 1). Although the EU’s legislative output has decreased in recent years, it still produces dozens of regulations and directives annually (European Commission 2016: 2–3). This legislation aims to solve a wide range of societal problems. To improve the effectiveness of EU legislation in solving such problems, the European Commission, which is the main actor responsible for evaluation in the EU, has developed a ‘better regulation’ agenda since 2000. Since 2007,Footnote 2 a key element of this agenda has been the systematic production of ex-post legislative (EPL) evaluations: reports that retrospectively assess the effects of EU legislation (European Commission 2007: 3, 2015: 7, 2016: 2).

EPL evaluations are supposed to enhance both the Commission’s accountability towards citizens and its capacity to learn based on factual evidence (European Commission 2015: 259; Fitzpatrick 2012: 478–479; Huitema et al. 2011: 183). Arguably, the importance of evaluations for learning is especially pertinent for EU legislation, because such legislation has highly uncertain effects. In particular, directives produced by the EU are implemented differently by its twenty-eight member states, each of which has its own policy traditions, which makes it difficult to learn how such legislation works in practice (Fitzpatrick 2012: 480–481).

Theoretically, the Commission’s EPL evaluations can be used for policy improvement in several ways. First, the evidence produced by EPL evaluations is supposed to feed into the ex-ante evaluations (impact assessments) that the Commission must attach to all its major proposals for legislative amendments (European Commission 2015: 258, 2016: 3). Second, evidence provided by EPL evaluations can be used by the Commission to improve delegated acts or to develop guidelines for the practical implementation of legislation. Third, EPL evaluations can provide information to stakeholders about a particular piece of legislation and allow them to push for changes accordingly (European Commission 2015: 280).

The Commission’s system for EPL evaluation is designed to enhance quality in three main ways. Firstly, whereas EPL evaluations are primarily the responsibility of the Commission’s Directorates-General (DGs), its Secretariat-General (SG) has set quality standards that all DGs must observe (European Commission 2007: 22–24, 2015: 252–298). Secondly, DGs outsource most of their EPL evaluations to specialized consultants to boost their technical quality (European Commission 2015: 282–289; Van Voorst 2017: 33–34). In such cases, the consultants conduct most of the evaluation, while the responsible DG monitors the quality of their work (European Commission 2015: 337–414; Fitzpatrick 2012: 490–497). Thirdly, the Commission’s Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB) (2018: 11) annually judges the quality of a small number of EPL evaluations. These reports are often revised when the RSB’s (2018: 12) opinion is negative.

Conceptualizing evaluation quality

This article uses four criteria to assess the quality of the Commission’s EPL evaluations. These criteria have been derived from Mayne and Schwartz (2005: 304–305), who developed them based on the methodological standards used by countries and international organizations that are frontrunners in the field of policy evaluation. The selected criteria are suitable for our research because they relate to general methodological standards used in the social sciences, such as validity and reliability. Since evaluations are essentially a form of applied social research, a good evaluation should meet most of these methodological standards (Mayne and Schwartz 2005: 305). Other frameworks for evaluation quality focus more on ethical and/or usefulness aspects and are therefore less suitable for our study.

The first criterion is a well-defined scope: the purpose and the topic of an evaluation must be properly specified (Mayne and Schwartz 2005: 304). If this criterion is not met, it is less likely to be clear what an evaluation’s results are about and how broadly they can be applied. These issues, in turn, make it difficult to learn from an evaluation. In the context of this article, the criterion of a well-defined scope means that the Commission’s EPL evaluations should clearly specify which intended outcomes of which piece of legislation they study.

The second criterion is accurate data: the raw information presented by an evaluation must be valid and reliable (Mayne and Schwartz 2005: 305). Validity refers to the absence of systematic errors in research results (Adcock and Collier 2001: 531) and can be further split into two types. The first type is internal or content validity: the correct measurement of abstract concepts (Adcock and Collier 2001: 538). The second type is external validity: the degree to which results based on a sample represent a whole population (Adcock and Collier 2001: 529). Reliability concerns the absence of random errors (Adcock and Collier 2001: 531).

In the context of this article, validity and reliability mean that the Commission’s EPL evaluations should avoid systematic and random errors, respectively. If this is not the case, learning is more likely to occur based on false information. This, in turn, may lead to poor or unsubstantiated decision-making (Cooksy and Caracelli 2005: 31; Mayne and Schwartz 2005: 7). External validity also matters for the Commission’s EPL evaluations because they must often make some selection of member states or stakeholders (Fitzpatrick 2012: 490). For such evaluations to contribute to learning about an entire piece of legislation, the results for the selected countries or actors must correctly represent the situation in the whole EU.

The third criterion is robust methodologyFootnote 3: evaluations should use methods that fit their research objective (Mayne and Schwartz 2005: 305). In the context of EPL evaluations experimental methods are often impossible, as legislation is universal and therefore leaves no room for a control group (Bussmann 2010: 281; Coglianese 2012: 404). Furthermore, legislation usually comprises multiple interventions. Like ‘policy accumulation’ more broadly, this leads to attribution problems (Adam et al. 2018: 270), reducing the utility of experimental designs (Bussmann 2010: 281). Arguably, the utility of experiments for EPL evaluations is even lower, because EU legislation is known for its great complexity (as is explained in detail in the theoretical section below). This legal complexity is hard to capture in an experimental design (Fitzpatrick 2012: 480).

Conversely, methodologies that involve stakeholders are highly fitting when evaluating EU legislation, as there are many different actors involved in the implementation of such policies (like member states, local governments and interest groups) (Fitzpatrick 2012: 481, 489). Stakeholders who implement policies in their daily work presumably have the best view on how they function (Varvasovszky and Brugha 2000). Thus, considering the views of multiple stakeholders makes it more likely that the results of an EPL evaluation will be of high quality.

The fourth criterion is substantiated findings: an evaluation’s conclusions should be based on its underlying data (Mayne and Schwartz 2005: 305). This criterion matters because actors who seek to use an evaluation may not have time to read it entirely and may therefore rely on its conclusions only (Vedung 1997: 281). When such conclusions are not clearly related to their underlying data, decision makers may have insufficient details to fully learn how a policy works (Coglianese 2012: 62–63). Furthermore, if a conclusion is not clearly supported by underlying data, this may create distrust in the validity of evaluations’ findings, making them less useful for accountability or learning (Forss and Carlsson 1997: 481, 490).

Theoretical framework

Although much academic literature about policy evaluation exists, there is no comprehensive theory that explains variation in evaluation quality (Mastenbroek et al. 2016: 1343). Therefore, this article develops an explanatory model for evaluation quality based on broader theories about EU governance and policy evaluation. In this model, we consider two types of variables that may affect evaluation quality: political and technical explanations.

Political explanations

EPL evaluations can be perceived as strategic tools in the hands of decision makers. This idea is rooted in the theoretical view that evaluations are never entirely neutral: their results are always advantageous to some actors while being disadvantageous to others (Bovens et al. 2008: 319; Chelimsky 2008: 400; Daviter 2015: 495; Versluis et al. 2011: 213–214; Weiss 1993: 95–96). For example, evaluations can be used strategically to delay decisions, to shift responsibilities for mistakes or to provide a semblance of rationality (Vedung 1997: 111–113).

Political pressure is generally considered a threat to evaluation quality (Cooksy and Mark 2012: 82; Datta 2011: 281). Potentially, it has a negative effect on all four quality criteria described above (Mayne and Schwartz 2005: 314–316). Political influence may prevent a well-defined scope when an evaluation’s client prescribes vague or suggestive research questions to serve his own interests (Chelimsky 2008: 404; Vedung 1997: 93–94). Accurate data is difficult to collect when actors refuse to provide evaluators with information that could harm their political position (Chelimsky 2008: 404; Weiss 1993: 96) or this information gets distorted because stakeholders are selectively involved in the evaluation process (Bovens et al. 2008: 321; House 2008: 417). The criterion of robust methodology is not met when unwelcome parts of data are ignored (Chelimsky 2008: 401; House 2008: 418). Finally, political pressure may have a negative effect on substantiated findings when the conclusion of an evaluation is rewritten to include findings favourable to specific actors or to drop results unwelcome to them (Chelimsky 2008: 404; House 2008: 418).

Academic literature about political interests in the EU (e.g. Majone 1999: 12; Pollack 2008: 20–21; Versluis et al. 2011: 125) usually focuses on institutional interests, since negotiations about EU policies primarily take place between institutions rather than between parties. As was explained in the introduction, the Commission is the main institution involved in EPL evaluations in the EU. Therefore, this article focuses on the interests of this actor.

Previous research has shown that the Commission deals strategically with the initiation and use of both impact assessments (Poptcheva 2013: 4; Torriti 2010: 1065) and EPL evaluations (Van Voorst and Mastenbroek 2017: 653; Van Voorst and Zwaan 2018). Therefore, we can expect strategic considerations to influence the quality of the Commission’s EPL evaluations as well. Below, this general expectation is translated into specific hypotheses.

Arguably, the risk of strategic considerations affecting evaluation quality is especially high when an evaluation’s topic is politically controversial (Boswell 2008: 473–476). According to this logic, the sensitivity of a piece of legislation increases the stakes of the actors involved in the evaluation process, which in turn increases the chances that they will take note of the evaluation and will attempt to distort its results in some of the ways that were described above. This may reduce the quality of the evaluation.

Hypothesis 1

The more politicized the topic of an EPL evaluation, the lower the quality of that evaluation.

A second important strategic consideration is that evaluations with negative results can lead to demands to reduce the role of actors responsible for policy implementation (Vedung 1997: 102–108). In the context of the EU, EPL evaluations may be used by the European Parliament (EP), the Council and other stakeholders to scrutinize the Commission’s activities (Radaelli and Meuwese 2010: 138; Versluis et al. 2011: 208). Therefore, EPL evaluations with negative findings may lead such actors to call for the Commission’s competences to be reduced and/or for policies to be ‘repatriated’ to the national level. We thus expect that the Commission will particularly wish to influence the results of EPL evaluations when there is a risk that these results may lead to significant legislative amendments.

Involvement of the EP in decision-making decreases the chances of significant amendments and is therefore expected to have a positive effect on evaluation quality. The reason for this is that the EP provides an extra veto player that can block amendments (Häge 2007: 307). As a majority of EP members generally supports further European integration (Pollack 2008: 9), it can also be expected that the EP will usually oppose reducing the competences of supranational institutions like the Commission.

Hypothesis 2

Evaluations of pieces of legislation for which the European Parliament has veto powers are of higher quality than evaluations of pieces of legislation for which the European Parliament does not have veto powers.

The voting procedure in the Council is also expected to influence the chances of legislative amendments. If unanimity is required in the Council, it is significantly harder to change legislation, as it is difficult to make all member states agree on a proposal (Häge 2007: 308). Theoretically, this difficulty to amend legislation reduces the risk that negative evaluation results will threaten the Commission’s competences and therefore decreases the incentive for the Commission to distort evaluation results. We therefore expect the quality of an evaluation to be higher when the Council applies unanimity voting, as compared to when it applies qualified majority voting (QMV).

Hypothesis 3

Evaluations of pieces of legislation decided upon by unanimity in the Council are of higher quality than evaluations of pieces of legislation decided upon by qualified majority voting.

The quality of the Commission’s EPL evaluations may also be affected by the presence of evaluation clauses in the evaluated legislation. Such clauses include legal obligations to evaluate the legislation in a certain way and at a certain moment in time (Summa and Toulemonde 2002: 410). These legal obligations may cause EPL evaluations to become ‘tick-the-box exercises’ which are only conducted because they are obligatory rather than as genuine efforts to learn about policies (Cooksy and Mark 2012: 82; Radaelli and Meuwese 2010: 146). When there is a lack of enthusiasm to evaluate, the quality of EPL evaluations may suffer. Evaluation clauses also prevent flexibility, as the timeframe of three to five years that they tend to prescribe may be too short to conduct a proper EPL evaluation.Footnote 4

Hypothesis 4

Evaluations of pieces of legislation containing an evaluation clause are of lower quality than evaluations of pieces of legislation containing no evaluation clause.

Technical explanations

Besides the political variables described above, evaluation quality may also be affected by ‘technical’ factors. Such factors are rooted in an apolitical or rationalistic perspective on policy evaluation. This view encompasses the idea that evaluations can produce objective knowledge when the correct procedures are followed and the right evaluators are involved in the process, regardless of political context (Bovens et al. 2008: 325).

Three specific technical factors may affect the quality of the Commission’s EPL evaluations. The first is evaluation capacity: the means and procedures meant to ensure that high-quality evaluations are ongoing practices within organizations (Nielsen et al. 2011: 325). Higher evaluation capacity can be expected to positively affect evaluation quality (Cooksy and Mark 2012: 81), as it allows for more investments in every stage of an evaluation process. For example, having a staff that is trained well in evaluation methods can lead to better data collection and analysis (accurate data and robust methodology) (Nielsen et al. 2011: 327). Furthermore, more evaluation capacity allows for extra investments in writing high-quality reports (Forss and Carlsson 1997: 498; Rossi et al. 2004: 414), which could lead to a more thorough description of the evaluated policy (well-defined scope) and to results being presented in a way that clearly links them to the underlying data (substantiated findings).

Within the Commission, the DGs are the main organizational units that conduct evaluations (Stern 2009: 71). Existing research (Van Voorst 2017: 33) shows that the capacity of these DGs to conduct EPL evaluations varies greatly: some DGs have clear procedures for EPL evaluations in place and invest much financial and human capital in them, while for other DGs less capacity is available. We expect that these capacity differences between DGs (partly) explain the variance in the quality of the Commission’s EPL evaluations.

Hypothesis 5

The higher the evaluation capacity of the DG that conducts an evaluation, the higher the quality of that evaluation.

A second technical factor that may affect evaluation quality is the type of evaluator. Although the Commission’s DGs outsource most of their EPL evaluations, they may also conduct them internally (European Commission 2015: 282–289). External evaluations can be expected to be of higher quality than internal ones, as they are generally conducted by more experienced evaluators (Vedung 1997: 117). Most DGs sign multi-annual framework contracts with specialized consultants, which allows these companies to gain expertise in evaluating EU legislation (Van Voorst 2017: 33–34), which may result in higher quality. Although DGs must also employ some evaluation experts internally, this is usually a small coordinating staff that has less experience with conducting full evaluations (Van Voorst 2017: 33).

Some academics (e.g. Vedung 1997: 117) suggest that external evaluators also produce better reports because they are more impartial than internal evaluators. Other literature disputes this claim, as the fact that consultants depend on policy makers for their future funding may give them an incentive not to be too critical (Conley-Tyler 2005: 7). All in all, we do not expect the difference in impartiality to affect the quality of EPL evaluations in the context of this article.

Hypothesis 6

External EPL evaluations are of higher quality than internal ones.

The third technical factor that may affect quality is legislative complexity. Legislation is often difficult to evaluate because it contains multiple overlapping interventions with different goals (Bussmann 2010: 281). This is especially the case in the context of the EU, where regulations and directives are based on extensive compromises between different member states and supranational institutions (Fitzpatrick 2012: 480–481; Häge 2007: 307–308). The implementation of EU legislation also typically involves a complex web of actors (Fitzpatrick 2012: 480; Steunenberg 2006: 294–295).

Such complexity can make it difficult to conduct high-quality EPL evaluations (Bussmann 2010: 281; Fitzpatrick 2012: 480–481). In particular, the fact that EU legislation often contains multiple goals and interventions can make it challenging to clearly delineate the topic of an EPL evaluation (well-defined scope). For complex legislation, it may also be more difficult to identify and gain access to all stakeholders and to find other appropriate sources of information (accurate data and robust methodology) (Bussmann 2010: 281; Fitzpatrick 2012: 480–481). Furthermore, for more complex legislation it may be harder to define when it should be considered successful, which makes it more difficult to draw conclusions from the available evidence (substantiated findings).

Hypothesis 7

The more complex the piece of legislation that is evaluated, the lower the quality of the evaluation.

Methods and data

Data collection

This research is based on a self-constructed dataset of 153 evaluations in which the Commission or an actor hired by the Commission retrospectively assessed the effectiveness of European regulations or directives. Our focus on effectiveness means that evaluations about process aspects or side effects of legislation only were left out. The Commission’s process evaluations often take the form of brief implementation reports, which we did not consider suitable to judge with the same criteria that we use for the effectiveness evaluations.

The dataset starts at January 2000 because of the lacking online availability of earlier EPL evaluations; it ends at December 2014 because not all evaluations from 2015 and later had been published online when we had completed our data collection. Three other types of EPL evaluations were discarded. Firstly, evaluations of legislation that only regulates the EU institutions or actors outside of the EU were left out, as the Commission’s better regulation agenda (and hence, its quality system) focuses on legislation that affects citizens and companies (European Commission 2007: 3, 2016: 2). Secondly, we discarded evaluation reports that merely summarize other evaluations. Thirdly, four EPL evaluations only available in French were left out because reading them would have required extensive knowledge of that language.

The evaluations were collected from various sources: the Commission’s search engine for evaluations,Footnote 5 the Commission’s multi-annual evaluation overview (2010), EU bookshop,Footnote 6 annexes to the Commission’s financial reports,Footnote 7 the Commission’s work programmes,Footnote 8 and lists of evaluations found on websites of the Commission’s DGs. The data collection was checked by using an existing dataset of evaluations from expertise centre Eureval, by running Google searches for evaluations of major legislation adopted between 1996 and 2010, by searching for background documents of legislation in Eur-lex,Footnote 9 and by discussions with the SG. For a further description of the dataset, see Mastenbroek et al. (2016: 1334–1335).

Operationalization of evaluation quality

The quality of each evaluation report was measured by coding it with the help of a standardized scorecard. This method has the advantage that it allows for studying a large number of evaluations in a short amount of time (Forss and Carlsson 1997: 483). Its disadvantage is that it is unfit to judge evaluation processes, which are usually not described in the reports. The scorecard method also does not allow for in-depth judgements of the content of individual evaluations. Therefore, this article focuses on characteristics of the reports that can be efficiently measured.

The criterion of a well-defined scope, firstly, was measured using two indicators. The first indicator is the presence of a clear problem definition: the report should mention its aim to measure the effectiveness of specific legislation before presenting its findings. The second indicator is the presence of a reconstruction of the legislation’s intervention logic: an overview of the steps through which the regulation or directive was intended to reach its goals. Such reconstructions matter because evaluations that seek to understand a policy’s effectiveness should first map how it was meant to work (Fitzpatrick 2012: 485; Stern 2009: 70).

Secondly, concerning accurate data, to check if an EPL evaluation measures effectiveness without too many errors, the various types of validity and reliability discussed in the theoretical section were measured. Content validity was assessed by checking the evaluations for the presence of a clear operationalization: a list of concrete indicators used to measure effectiveness. External validity was measured by using two indicators: a representative selection of member states and a representative selection of cases within these states. Unless all countries or cases were selected, the evaluation had to provide a clear explanation for the representativeness of its selection. Reliability was assessed by checking the replicability of the evaluations: do the reports provide their questionnaires, lists of respondents and the like, so that the research could be repeated?

The criterion of robust methodology, thirdly, was assessed by checking the evaluations for the presentation of at least some stakeholder opinions regarding legislative effectiveness. A second indicator was the use of triangulation: are the evaluation’s findings based on at least two different methods of data collection? Triangulation is a sign of methodological robustness because it allows for double-checking findings about effectiveness. The following methods were counted as substantially different when measuring triangulation: studying existing content, direct observations, surveys, focus groups and interviews.

The criterion of substantiated findings, fourthly, was assessed by checking if the reports clearly link their conclusions to their results. Specifically, the evaluations were required to (1) contain a conclusion that judges the legislation’s effectiveness and (2) provide clear sources or references to data presented earlier in the report in a majority of this conclusion’s paragraphs. Only paragraphs that answered research questions were included in this calculation: opening paragraphs and paragraphs that merely served to structure the conclusion were not counted.

Each indicator presented above was measured dichotomously, with evaluation reports that provided no information about a certain indicator automatically being coded as zero. Twenty cases were coded by both authors of this article to assess intercoder reliability, which was found to be sufficient.Footnote 10 Table 1 summarizes the indicators of the scorecard.

Operationalization of independent variables

Politicization (hypothesis 1) was measured by establishing whether or not the evaluated legislation was on the Council’s agenda as a B-point. B-points are usually issues which the Council’s civil servants move up to the political/ministerial level because of their sensitivity (Häge 2007: 303), which makes this an appropriate indicator for politicization. Involvement of the European Parliament (hypothesis 2) was measured by assessing the formal procedure used to enact the evaluated legislation as stated by Eur-lex (See Footnote 9). In case of the ordinary legislative procedure (former codecision and cooperation procedures), this involvement was considered high, while in case of the consultation and comitology procedures it was considered low (Häge 2007: 316). The voting procedure in the Council (hypothesis 3) was also measured dichotomously (QMV or unanimity) using Eur-lex. The presence of an evaluation clause (hypothesis 4) was measured dichotomously (yes/no) by searching each evaluated piece of legislation using specific keywords.Footnote 11

Evaluation capacity (hypothesis 5) was measured via interviews with the evaluation coordinators of seventeen DGs of the Commission, which were conducted in the context of another study related to this article (Van Voorst 2017: 29–31). Data were collected about twelve capacity indicators, but out of these only the presence of a dedicated (sub)unit for evaluations (yes/no) and the presence of evaluation guidelines (yes/no) could be established per DG per year and were therefore useful for this research (for details, see Van Voorst 2017). The type of evaluator (hypothesis 6), which could be either internal or external, was deduced from the title pages of the reports. The complexity of the evaluated legislation (hypothesis 7) was measured by its number of recitals. Such recitals are explanations listed at the beginning of legislative texts. Since more complex legislation usually requires more explanations, the number of recitals is often used as an indicator for legislative complexity (Kaeding 2006: 236).

Some of the indicators presented above were derived from the evaluated legislation. When multiple pieces of legislation were studied by one evaluation, the average score for these pieces of legislation was used to code continuous variables and the type of the majority of the pieces of legislation was used to code the categorical ones. For example, if an evaluation studied two pieces of legislation with an evaluation clause and one piece of legislation without such a clause, it was coded as containing a clause. In the rare case of a tie, we used the value of the most recent legislation. Table 2 summarizes the operationalization, which has partly been derived from Van Voorst and Mastenbroek (2017: 648–649).

Method of analysis

The data presented above were analysed using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. One assumption of this technique is that the dependent variable is continuous (Miles and Shevlin 2001: 62), which is not the case for evaluation quality as measured in this article. However, if the number of categories used to measure an ordinal variable is large enough (e.g. higher than seven) it can still be analysed with OLS regression if all other assumptions of this method are met (Miles and Shevlin 2001: 62). We carefully checked for these assumptions and found that none of them were violated by our data. We preferred OLS regression over regression methods tailored towards ordinal variables because its results are easier to interpret. The variables were entered in two blocks that match the two types of explanations described above.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Figure 1 depicts the variance in the quality of the 153 evaluations studied in this article. The average quality score is 5.6 on a nine-point scale; about 75% of the reports meet the majority (five or more) of the criteria. No reports received a score of zero and only five reports received a score of one or two. At the other end of the spectrum, two reportsFootnote 12 meet all of the criteria and sixteen reports meet all but one of them.

Overall, this assessment of the 153 cases that focus on effectiveness provides a more positive picture than an earlier study of 216 EPL evaluations produced by the Commission between 2000 and 2012, where the average quality score was 4.1 on an eight-point scale, 43% of the reports met five or more out of eight criteria and two reports received a score of zero (Mastenbroek et al. 2016: 1340). This comparison suggests that the Commission’s EPL evaluations that assess effectiveness are of a somewhat higher quality than its ex-post evaluations of other aspects of legislation (like transposition, implementation or side effects).

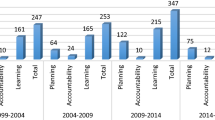

However, the quality of the evaluations does not seem to increase over time. As Fig. 2 depicts, it has remained fairly consistent throughout the years 2000–2014.

Table 3 presents the number of EPL evaluations with a positive score per aspect of quality. The table shows that there are large differences between the criteria. The vast majority of the evaluations apply stakeholder consultation and at least one other data collection method (about 76% has a positive score regarding both stakeholder consultation and triangulation), which means that the criterion of a robust methodology is generally met. The criterion of a well-defined scope is only partly met: although almost all of the Commission’s EPL evaluations include a clear problem definition (89%), only a minority of them goes beyond that by also presenting the intervention logic through which the evaluated legislation is supposed to achieve its aims (37%). Substantiated conclusions are present in a small majority of 57% of the reports, which means that more than four out of ten evaluations have no conclusion that can be clearly linked to its collected data.

Overall, the criterion of accurate data is met by the smallest proportion of EPL evaluations. Although 70% of the reports study all member states or clearly explain their selection of certain countries, only 42% of them are fully transparent about how they selected cases within these states. This shows that the external validity of many EPL evaluations is questionable. Some 64% of the EPL evaluations present a clear operationalization that shows how the legislation’s effectiveness was measured, which is important for their internal validity. However, few evaluations meet the standard set for reliability: only 31% of them present all the information that would be needed to repeat their underlying research. In particular, many EPL evaluations present either their interview guides, their questionnaires or their lists of respondents, but not all of this information together, making it impossible to check the data collection if required.

A recent study by the European Court of Auditors (2018) of EPL evaluations conducted by four DGsFootnote 13 presented mostly similar findings on justification of methods. According to the report, little more than half of the sampled evaluations comprehensively explained their chosen methodology, and little more than one-third of the evaluations justified their choice of methods (European Court of Auditors 2018: 24). At the same time, the great majority of reports (80%) were transparent on data limitations. In sum, the Court concluded that ‘while the methodology chosen is usually outlined, it is not detailed enough to allow for a good understanding of its strengths and weaknesses’ (ibid: 35).

Explanatory analysis

Having identified marked inter-report variance in quality, we now proceed with our explanatory analysis, the results of which are presented in Table 4. As the table shows, the model with the political factors only (model 1) is significant at the 0.05 level, but explains just 6% of the variance in the quality of the EPL evaluations. Furthermore, none of the individual independent variables included in this model turn out to be significant in the way the hypotheses predicted. The level of politicization of the evaluated legislation (hypothesis 1), the procedure through which it was enacted by the Council (hypothesis 3) and the presence of an evaluation clause in its text (hypothesis 4) do not explain the variance in the quality of subsequent EPL evaluations.

The voting procedure used in the EP does provide a significant explanation, but its effect is the opposite of what we expected based on our theoretical framework (hypothesis 2). On average, the quality of EPL evaluations of legislation enacted through the ordinary legislative procedure is about one point lower than the quality of EPL evaluations of legislation enacted through the consultation procedure. This effect remains significant no matter which of the other factors are included in the model. This result suggests that, contrary to our expectations, the Commission’s interest to protect its competences does not explain the variation in the quality of its EPL evaluations. However, it should be noted that the indicators used to measure this interest were fairly general proxies.

One possible reason for the fact that EPL evaluations of legislation enacted through the ordinary procedure are of relatively low quality could be that such legislation is more closely scrutinized by the EP than legislation enacted through the consultation procedure (Rasmussen and Toshkov 2010: 92). The Commission could therefore have an incentive not to provide the EP with EPL evaluations that can be used for the purpose of this scrutiny. However, more (qualitative) research about the mechanisms behind the Commission’s EPL evaluations would be needed to assess the plausibility of this hypothesis.

Table 4 shows that when the technical variables are added (model 2), the model as a whole is still significant at the 0.05 level and its explanatory power increases greatly to 0.34. This means that the model with all variables included explains about one-third of the variation in the quality of the EPL evaluations. Out of the added variables, only the type of evaluator is significant (in line with hypothesis 6). On average, external evaluations score almost two points higher than internal evaluations on the nine-point scale used in this article. Based on our theoretical framework, the most logical interpretation of this finding is that external evaluators produce EPL evaluations of higher quality because they have more specialized expertise than the Commission’s internal evaluators.

Four individual quality aspects correlate significantly with the type of evaluator.Footnote 14 These four criteria are listed here together with the proportion of external evaluations versus the proportion of internal evaluations that meets them: (1) a clear operationalization (77% vs. 18%), stakeholder consultation (87% vs. 73%), triangulation (98% vs. 58%) and substantiated conclusions (66% vs. 24%). For the other criteria, the difference between both types of evaluators is about 10% or less. Based on these findings, outsourcing evaluations to consultants seems to be particularly useful to produce reports that have high internal validity, a robust methodology and substantiated findings.

The other three technical variables included in the analysis provide no significant explanations. In other words, this article found no evidence that DGs with more evaluation capacity produce better EPL evaluations than other DGs (hypothesis 5), nor do the data show that legislative complexity negatively affects the quality of EPL evaluations (hypothesis 7).

Conclusion

This article aimed to describe and explain the variance in the quality of the European Commission’s ex-post evaluations that assess legislative effectiveness. To achieve this goal, a dataset of 153 ex-post legislative (EPL) evaluations was analysed with the help of OLS regression, to test hypotheses derived from a political and a technical view on EPL evaluations.

The descriptive results show that the quality of the Commission’s EPL evaluations varies considerably. The average quality score of the reports is 5.6 on a nine-point scale. Most of the evaluations present both stakeholder input and other data, which indicates that their methodology is based on a robust combination of sources. However, the evaluations perform less well regarding the clarity of their scope, the accuracy of their data and the foundations underpinning their conclusions. The worst aspect of the evaluations’ quality is their replicability: less than one-third of the reports contain all the material required to repeat their research.

The explanatory analysis shows that the type of evaluator is a significant explanation for the variation in quality. In other words, external evaluators produce considerably better EPL evaluations than the Commission’s internal services. This finding suggests that the expertise of specialized consultants is a key asset to enhance evaluation quality. None of the other factors that we studied were found to be significant in the way that we expected. The role of parliamentary involvement has an opposite effect from our hypothesis: a stronger role for the EP correlates with lower, not higher evaluation quality. This suggests that political factors can be important in explaining evaluation quality, but in a different way than we expected.

This article has three main limitations. Firstly, it does not prove why certain factors influence evaluation quality. For example, do external evaluators deliver more quality because they have more expertise (as our theoretical framework suggests) or because they are more independent than internal evaluators? A second limitation is that this article focuses on those quality indicators that could be efficiently measured. Therefore, criteria related to evaluation processes or the detailed content of reports were omitted. One way to address these limitations would be to conduct case studies on a number of specific evaluations, so their quality can be described and explained in greater depth. Third, this study was built on the assumption that evaluation quality is a necessary condition for learning and accountability. This assumption itself has not been scrutinized, which would be a fruitful first avenue of research, especially in the light of the claim that policy learning itself may be political (Mead 2015).

Additionally, our results raise the question of external validity: what are their implications for governance units beyond the EU? First, the quality of EPL evaluations is likely to be even less developed in the great majority of OECD countries, since most of them have weaker systems for conducting such evaluations than the EU (OECD 2015: 30, 141–211). Second, executives that are less technocratic than the European Commission are likely to have even lower evaluation quality, given the stronger political environment in which they operate. For this reason, states with a more politicized executive and a strong system for EPL evaluation, like the US, would be particularly interesting cases for follow-up research.

Finally, our study produces important policy recommendations. With an eye on learning and accountability, the limited quality of the EPL evaluations that we studied is worrying: doubts about evaluations’ quality may hinder their credibility and use, and ultimately the legitimacy of the Commission’s evaluation system. We therefore recommend the Commission to outsource its EPL evaluations even more rigorously than it does today. Although evaluations of EU legislation are inherently political, it might be possible to ensure greater quality control when external actors are involved. For similar reasons, it seems wise to strengthen the role of the Commission’s Regulatory Scrutiny Board (2018: 11–12), which could scrutinize the evaluations’ quality more strictly.

Notes

While the European Parliament (EP) has to appoint the whole Commission and can remove it from office, its individual members are proposed by the EU member states and cannot be sent home by the EP. Additionally, the Commissioners are to act in the common European interest, which further reduces the scope for (party-)politics.

We have included reports from both before and after 2007 in our dataset, since we see no reason why the fact that legislation is evaluated more systematically (i.e. on a larger scale) since that year should change the criteria used to assess the quality of these evaluations.

Mayne and Schwartz (2005: 305) label this aspect ‘sound analysis’, but we prefer the name ‘robust methodology’, as the former seems more related to the criterion of substantiated findings.

The Commission’s Regulatory Scrutiny Board stressed this point during informal discussion with us in May 2017.

SWD(2013)228 and SWD(2012)383.

Cohen’s Kappa was between 0.65 and 1.0 for each indicator, indicating a sufficient degree of intercoder reliability (Neuendorf 2002: 143).

‘evalu*’, ‘repo*’, ‘stud*’ and ‘research’. We also checked the last five articles of each directive or regulation, where evaluation clauses are most commonly found.

The Evaluation of the Measures under Regulation (EC) No 951/97 and the Fitness Check of the Operation and Effects of Information and Consultation Directives in the EU/EEA Countries.

DG Environment; DG Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs; DG Migration and Home Affairs; DG Health and Food Safety.

The correlations of the four listed aspects with the type of evaluator are, respectively, 0.50, 0.17, 0.55 and 0.35.

References

Adam, C., Steinebach, Y., & Knill, C. (2018). Neglected challenges to evidence-based policy-making: The problem of policy accumulation. Policy Sciences,51(3), 269–290.

Adcock, R., & Collier, D. (2001). Measurement validity: A shared standard for qualitative and quantitative research. The American Political Science Review,95(3), 529–546.

Boswell, C. (2008). The political functions of expert knowledge: Knowledge and legitimization in European Union immigration policy. Journal of European Public Policy,15(4), 471–488.

Bovens, M., ‘t Hart, P., & Kuipers, S. (2008). The politics of policy evaluation. In R. E. Goodin, M. Rein, & M. Moran (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public policy (pp. 320–335). Oxford: University Press.

Bussmann, W. (2010). Evaluation of legislation: Skating on thin ice. Evaluation,16(3), 279–293.

Chelimsky, E. (2008). A clash of cultures: Improving the “Fit” between evaluative independence and the political requirements of a democratic society. American Journal of Evaluation,29(4), 400–415.

Coglianese, C. (2012). Evaluating the performance of regulation and regulatory policy. Report to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development.

Conley-Tyler, M. (2005). A fundamental choice: Internal or external evaluation? Evaluation Journal of Australasia,4(1), 3–11.

Cooksy, L. J., & Caracelli, V. J. (2005). Quality, context and use. Issues in achieving the goals of meta-evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation,26(1), 31–42.

Cooksy, J. M., & Mark, M. M. (2012). Influences on evaluation quality. American Journal of Evaluation,33(1), 79–89.

Datta, L. (2011). Politics and evaluation: More than methodology. American Journal of Evaluation,32(2), 273–294.

Daviter, F. (2015). The political use of knowledge in the policy process. Policy Sciences,48(4), 491–505.

European Commission. (2007). Responding to strategic needs: Reinforcing the use of evaluation [SEC(2007) 213]. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2010). Multi-annual overview (2002–2009) of evaluations and impact assessments. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/secretariat_general/evaluation/docs/multiannual_overview_en.pdf. Retrieved from July 10, 2015.

European Commission. (2015). Better regulation toolbox [SWD(2015) 111]. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2016). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council. Better regulation: Delivering better results for a stronger Union [COM(2016) 615 final]. Brussels: European Commission.

European Court of Auditors. (2018). Ex-post review of EU legislation: A well-established system, but incomplete [Special Report no 16]. Luxembourg: European Court of Auditors.

Fitzpatrick, T. (2012). Evaluating legislation: An alternative approach for evaluating EU internal market and services law. Evaluation,18(4), 477–499.

Forss, K., & Carlsson, J. (1997). The quest for quality—Or can evaluation findings be trusted? Evaluation,3(4), 481–501.

Häge, F. M. (2007). Committee decision-making in the council of the European Union. European Union Politics,8(3), 299–328.

House, E. R. (2008). Blowback: Consequences of evaluation for evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation,29(4), 416–426.

Huitema, D., Jordan, A., Massey, E., Rayner, T., Asselt, H., Haug, C., et al. (2011). The evaluation of climate policy: Theory and emerging practice in Europe. Policy Sciences,44(2), 179–198.

Kaeding, M. (2006). Determinants of transposition delay in the European Union. Journal of Public Policy,26(3), 229–253.

Majone, G. (1999). The regulatory state and its legitimacy problems. West European Politics,22(1), 1–24.

Mastenbroek, E., Van Voorst, S., & Meuwese, A. (2016). Closing the regulatory cycle? A meta-evaluation of ex-post legislative evaluations by the European Commission. Journal of European Public Policy,23(9), 1329–1348.

Mayne, J., & Schwartz, R. (2005). Assuring the quality of evaluative information. In R. Schwartz & J. Mayne (Eds.), Quality Matters: Seeking confidence in evaluating, auditing and performance reporting (pp. 1–17). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Mead, L. M. (2015). Only connect: Why government often ignores research. Policy Sciences,48(2), 257–272.

Miles, J., & Shevlin, M. (2001). Applying regression and correlation: A guide for students and researchers. London: Sage.

Mousmouti, M. (2012). Operationalising quality of legislation through the effectiveness test. Legisprudence,6(2), 191–205.

Neuendorf, K. (2002). The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Nielsen, S. B., Lemire, S., & Skov, M. (2011). Measuring evaluation capacity: Results and implications of a Danish study. American Journal of Evaluation,32(3), 324–344.

OECD. (2015). OECD regulatory policy outlook 2015. Paris: OECD Press.

Pollack, M. A. (2008). Member-state principals, supranational agents, and the EU budgetary process, 1970–2008. Paper prepared for presentation at the Conference on Public Finances in the European Union, sponsored by the European Commission Bureau of Economic Policy Advisors, Brussels, 3–4 April 2008.

Poptcheva, E. M. (2013). Library briefing. Policy and legislative evaluation in the EU. Brussels: European Parliament.

Radaelli, C. M., & Meuwese, A. C. M. (2010). Hard questions, hard solutions: Proceduralisation through impact assessment in the EU. West European Politics,33(1), 136–153.

Rasmussen, A., & Toshkov, D. (2010). The inter-institutional division of power and time allocation in the European Parliament. West European Politics,34(1), 71–96.

Regulatory Scrutiny Board. (2018). Regulatory scrutiny board—Annual report 2017. Brussels: European Commission.

Rossi, P. H., Lipsy, M. W., & Freeman, H. E. (2004). Evaluation: A systematic approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Sanderson, I. (2002). Evaluation, policy learning and evidence-based policy making. Public Administration,80(1), 1–22.

Schoenefeld, J. J., & Jordan, A. J. (2019). Environmental policy evaluation in the EU: Between learning, accountability, and political opportunities? Environmental Politics,28(2), 365–384.

Stern, E. (2009). Evaluation policy in the European Union and its institutions. In W. M. K. Trochim, M. M. Mark, & L. J. Cooksy (Eds.), Evaluation policy and evaluation practice: New directions for evaluation (pp. 67–85). San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

Steunenberg, B. (2006). Turning swift policymaking into deadlock and delay: National policy coordination and the transposition of EU directives. European Union Politics,7(3), 293–319.

Summa, H., & Toulemonde, J. (2002). Evaluation in the European Union: Addressing complexity and ambiguity. In J. Furubo, R. C. Rist, & R. Sandahl (Eds.), International atlas of evaluation (pp. 407–424). New Brunswick: Transaction.

Torriti, J. (2010). Impact assessment and the liberalization of the EU energy markets: Evidence-based policy-making or policy-based evidence-making? Journal of Common Market Studies,48(4), 1065–1081.

Van Aeken, K. (2011). From vision to reality: Ex-post evaluation of legislation. Legisprudence,5(1), 41–68.

Van Voorst, S. (2017). Evaluation capacity in the European Commission. Evaluation,23(1), 24–41.

Van Voorst, S., & Mastenbroek, E. (2017). Enforcement tool or strategic instrument? The initiation of ex-post legislative evaluations by the European Commission. European Union Politics,17(4), 640–657.

Van Voorst, S., & Zwaan, P. (2018). The (non-)use of ex-post legislative evaluations by the European Commission. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1449235.

Varvasovszky, Z., & Brugha, R. (2000). How to do (or not to do) a stakeholder analysis. Health Policy and Planning,15(3), 338–345.

Vedung, E. (1997). Public policy and program evaluation. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Versluis, E., Van Keulen, M., & Stephenson, P. (2011). Analyzing the European Union policy process. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan.

Weiss, C. H. (1993). Where politics and evaluation research meet. American Journal of Evaluation,14(1), 93–106.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van Voorst, S., Mastenbroek, E. Evaluations as a decent knowledge base? Describing and explaining the quality of the European Commission’s ex-post legislative evaluations. Policy Sci 52, 625–644 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-019-09358-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-019-09358-y