Abstract

Although the risk of flooding poses a serious threat to the Dutch public, citizens are not very inclined to engage in self-protective behaviors. Current risk communication tries to enhance these self-protective behaviors among citizens, but is nonetheless not very successful. The level of citizens engaging in self-protective actions remains rather low. Therefore, this research strives to determine the factors that might enhance or lessen the intention to engage in self-protection among citizens. The study was a 2 (flood risk: high vs low) × 2 (efficacy beliefs: high vs low) between subject experiment. It was conducted to test how varying levels of flood risk and efficacy beliefs influence two different self-protective behaviors, namely information seeking and the intention to engage in risk mitigating or preventive behaviors. Furthermore, the relationship between information seeking and the intention to take self-protective actions was discussed. Results showed that high levels of flood risk lead to higher levels of both information seeking and the intention to engage in self-protective behaviors than low levels of flood risk. For efficacy beliefs, the same trend occurred. Also, results showed that information seeking seems to coincide with the intention to take preventive actions and acted as a mediator between the levels of perceived risk and efficacy and the intention to take self-protective actions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Floods pose a common threat to many heavily populated coastal areas around the world (Maaskant et al. 2009). The Netherlands is situated in a delta area, partly below sea level, bordered by the North Sea, with several major rivers flowing through the country. In terms of the severity of the consequences, floods can be seen as the most serious natural hazard of the country. Although many high-quality precautionary measures are being taken against flooding, and flooding actually is a low-probability risk, no certainty exists about whether flooding may occur in the future when climatic conditions change (Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management 2006).

Influenced by European rules and regulations and with the catastrophic events in New Orleans after the hurricane Katrina as a warning sign, the Dutch government is re-inventing its role in preventing and mitigating calamities, like disastrous flooding. In this process, the notions about the role and responsibilities of individual citizens in taking risk-preparation activities also change. The government is aware that it cannot give the Dutch citizen a 100% calamity protection guarantee. The protection of the public is best served by encouraging additional self-protective measures and resilience (de Wit et al. 2008). Citizens are expected to proactively prepare themselves for flood risks to increase their personal safety (Grothmann and Reusswig 2006). These prevention actions undertaken by residents may also reduce economic damages of floods considerably (Fink et al. 1996).

To motivate citizens to adopt preventive behaviors, different governmental campaigns have been established in the Netherlands, like the ‘denk vooruit’ (think ahead) campaign (www.crisis.nl). Information regarding those risks can be reached via municipal and provincial Web sites and can easily be linked to the own residence by entering a postal code. The question is whether this campaign sufficiently motivates people to prepare for the risk of flooding. Several studies have shown that relatively few people inform themselves by visiting the ‘think ahead’ Web site, only few people indicate to take self-protective measures with regard to flooding, and the risk perception with regard to flooding in the Netherlands is generally low (Terpstra 2010; Gutteling et al. 2010). The lack of motivation to prepare for floods is not only observed in the Netherlands. But research in other European countries like Germany, Norway, Sweden, and the UK indicates that over 80% of all respondents had not undertaken activities to mitigate future losses or to prepare for flood emergencies (Krasovskaia 2005). Additional research in different regions in the Netherlands by Terpstra and Gutteling (2008) has pointed out that very few citizens engage in self-protective behaviors with regard to flood risks. They do not take precautionary actions, nor do they show signs of adaptive behaviors with regard to flood risks. These results seem surprising as floods do pose a serious threat to the Dutch population, and the government does strive to promote self-protective actions through campaigns.

2 Theory and hypotheses

The question in this study is how (flood risk) information can help to stimulate the adoption of self-protective behavior. In this paper, we take the position that the lack of adopting self-protective measures in the case of flood preparedness is due to at least two conditions. The first is that, as studies indicate, Dutch people do not seek flood risk information and without information seeking, there is no exposure. And without exposure, no effect is to be expected. So the determinants of risk information seeking with respect to flood risk are studied (Kahlor 2007; Ter Huurne and Gutteling 2008). This could fit well with the signaled policy change where individual citizens are asked to take more responsibility for flood risk preparation. This increased awareness of responsibility could become manifest in a more active risk information-seeking role of the citizen. This approach implies a focus on mass-mediated information. Given the urgency of the issue, and the size of the targeted audience (>10 million people), other risk communication approaches seem less obvious at the moment.

The second condition is that existing flood risk information may not be effective in promoting self-protective behavior. There is no empirical evidence of the flood risk information’s efficacy. And neither is the information based on risk communication theory or best practices. The research question here is how the determinants of individual risk information seeking can be applied to make the information more effective in stimulating the adoption of self-protective measures.

2.1 Information seeking

The seeking of information has emerged as an important topic within risk communication over the past few years and can be described as a deliberate effort to acquire information in response to a need or gap in ones knowledge (Griffin et al. 1999; 2008; Case et al. 2005). Campaigns are often established under the assumption that all residents are susceptible to certain risks and threats faced by society and that they will more or less naturally seek for the provided information on the different risk topics (Sjoberg 2002). However, residents’ information seeking is not as straightforward as it might seem. Individuals do not always seek relevant risk information or may even avoid information (Miller 1987). This calls for an understanding of the factors that may influence the ways in which people respond to risk information and determine whether to attend to it or not.

The Framework for Risk Information Seeking (FRIS) (ter Huurne 2008; Kievik et al. 2009) focuses explicitly on the determinants of individual information seeking with respect to risk and safety. It proposes that three awareness factors may account for the perceived need for additional information in a risk setting. These factors are the perceived level of risk (‘is there a threat?’), personal involvement (‘is the threat relevant to me?’), and self-efficacy (‘am I able to deal with the threat?’). Perceived risk is seen here as the perception of the risk related to the event “flooding”. Personal involvement, sometimes labeled as personal risk, relates to the probability that a flood will have severe personal consequences (death, injury, property damage, or social disruption) (see e.g., Lindell and Perry 2000). Self-efficacy has been defined in several ways, but here we follow Bandura’s (1997) definition that states that it refers to one’s belief that one is able to execute a specific task successfully. In this case, this might refer to successfully deal with the threat of a flood by seeking information that will help to take adequate self-protective measures. Furthermore, FRIS states that, when risk and efficacy beliefs are made salient, risk perception and efficacy beliefs jointly affect subsequent action. Thus, the level of perceived risk and efficacy may be crucial factors in facilitating the information-seeking process. As the level of both these factors seem to be low among citizens with regard to flood risks (e.g., Terpstra and Gutteling 2008; Grothmann and Reusswig 2006), FRIS would predict a low level of information seeking among citizens, creating unfavorable conditions for effective risk communication.

2.2 The intention to take risk mitigating or preventive actions

Research contributed to our understanding why Dutch citizens do not engage in flood risk self-protective actions (e.g., Terpstra and Gutteling 2008). Firstly, the level of risk perception that citizens experience with regard to flood risks is low. As moderate to high levels of risk perception are seen as necessary conditions for individuals to take action, this might be one explanation for the lack of motivation to take precautionary measures among residents (Miceli et al. 2007). Secondly, citizens of areas prone to flooding seem to have low levels of both self-efficacy (‘am I able to deal with the threat?’) and response efficacy (‘is the advice that I get to deal with the threat useful in the sense that it will successfully help me to cope with the threat?’). That is, citizens do not know whether they are capable of executing actions that may reduce their vulnerability to flood risks (low level of self-efficacy), and they are uncertain that advised actions may be effective in mitigating the threat (low level of response efficacy) (Grothmann and Reusswig 2006). Research indicates, however, that for an individual to take precautionary measures, certain levels of self-efficacy and response efficacy are required (Rimal and Real 2003). The combination of elevated levels of risk perception, self-efficacy, and response efficacy would motivate people to adopt self-protective measures (Witte 1992; Smith et al. 2007).

One way to increase risk perception would be the use of fear appeal messages (Witte and Allen 2000; Kievik et al. 2009). The evaluation of a fear appeal initiates two appraisals of the message, which result in one of three outcomes (Witte 1992). First, individuals appraise the threat of an issue from a message. The more individuals believe they are susceptible to a serious threat, the more motivated they are to evaluate the efficacy of the recommended response. If the threat is perceived as irrelevant or insignificant, then there is no motivation to further process the message, and people will simply ignore the fear appeal. In contrast, when a threat is believed to be serious and relevant, individuals may become motivated to take some sort of action to reduce the induced level of fear (Witte and Allen 2000).

Perceived efficacy (composed of self-efficacy and response efficacy) determines whether people will become motivated to control the danger or control their fear about the threat. When people believe they are able to perform an effective recommended response against the threat (i.e., the advise is perceived as high with regard to self-efficacy [‘I can deal with the threat’] and response efficacy [‘the advice I get how to deal with the threat is useful’]), they are motivated to control the danger and consciously think about ways to remove or lessen the threat. Under these conditions, people carefully think about the recommended responses advocated in the persuasive message and adopt those as a means to control the danger. Alternatively, when people are uncertain about the effectiveness of recommended actions (i.e., the advise is perceived as low on self-efficacy and/or response efficacy), they are motivated to control their fear through denial, defensive avoidance, or reactance (Witte and Allen 2000).

Thus, the risk communication literature suggests that perceived threat contributes to the extent of a response to a fear appeal, whereas perceived efficacy (or lack thereof) contributes to the adaptive of maladaptive nature of the response. That is whether people will take adequate risk-mitigating actions or not. If no information with regard to the efficacy of the recommended response is provided, individuals will rely on past experiences and prior beliefs to determine perceived efficacy (Zaalberg et al. 2009). It thus seems that, for residents to engage in self-protective behaviors, two demands must be met. First of all, the level of aroused fear must be high. According to Witte and Allen’s (2000) Extended Parallel Processing model, the stronger the fear appeal, the greater the fear aroused, the greater the severity of the threat perceived, and the greater the susceptibility (personal risk) to the threat perceived. In this study, we assume that the stronger levels of fear appeal will lead to higher levels of perceived risk and personal involvement. Secondly, the level of perceived efficacy should be high as well. Not only is the ‘fear message’ of importance but also the (self and response) efficacy message that is attached to the fear appeal. When both self and response efficacy are strong, that is, when people are convinced, they can perform the behavior and the behavior is seen as successful in the mitigation of the risk, engaging in self-protective behavior will probably be the result. Furthermore, when both levels of perceived risk and (self and response) efficacy are high, individuals will seek for relevant information and take precautionary measures to protect themselves against risks like flooding.

2.3 Hypotheses

The aim of the current study is to determine the effect of levels of risk perception and efficacy beliefs on the actual information seeking and the risk information-seeking intention and the intention to take self-protective behaviors for flooding risk. With regard to the information seeking, the following hypotheses are formulated.

H1a

High levels of risk perception lead to higher levels of both the actual information seeking and the intention to seek information than low levels of risk perception.

H1b

High level of efficacy beliefs leads to higher levels of both the actual information seeking and the intention to seek information than low levels of efficacy beliefs.

With regard to the intention to take precautionary action, two hypotheses have also been established.

H2a

High levels of risk perception lead to higher levels of intention to take risk mitigating of preventive behaviors than low levels of risk perception.

H2b

High levels of efficacy beliefs lead to higher levels of intention to take risk mitigating of preventive behaviors than low levels of efficacy beliefs.

Furthermore, we aimed to understand how the seeking of information contributes to the adoption of risk mitigating and preventive behaviors. Since the assumption is that the same factors that predict the information-seeking process derived from FRIS (risk perception and efficacy beliefs) underlie the intention of citizens to engage in protective actions, we predict that information seeking predicts the intention to adopt self-protective measures.

H3

A high level of both actual information seeking and the intention to seek information leads to higher levels of intention to take risk mitigating of preventive behaviors than low levels of information seeking.

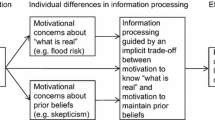

Finally, we wanted to test whether actual information seeking is a mediator (see Baron and Kenny 1986 p. 1176) between the independent variables risk perception and efficacy beliefs, and the dependent variable intention to take risk-mitigating or self-protective behavior (Fig. 1).

Since the aim of governmental campaigns is to enhance the self-protectiveness among citizens (Grothmann and Reusswig 2006), and the assumption is that the seeking of information is an essential link between the risk campaign and individual risk information processing (Griffin et al. 1999), information seeking is assumed to mediate the relationship between the provided stimuli and behavior. Testing will make clear whether seeking of risk information indeed adds upon providing stimuli alone or not. Therefore, the final hypothesis that has been established is as follows:

H4

Information seeking acts as a mediator between the independent variables risk perception and efficacy beliefs, and the intention of respondents to take risk-mitigating or self-protective actions.

3 Method

3.1 Design and procedure

The study was a 2 (flood risk: high vs low) × 2 (efficacy: high vs low) between subjects experiment. Table 1 presents the main characteristics of the four conditions in the experiment. In September and October 2009, randomly chosen inhabitants of various low-lying parts of the Netherlands were invited by letter to participate in the study. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four groups by sending each respondent randomly one of four established invitation letters corresponding to one of the four conditions. These letters contained a Web site link, giving respondents access to the corresponding online questionnaire.

After entering the questionnaire, participants were told that they participated in a study exploring the thoughts and feelings of citizens with regard to flood risks.

3.1.1 Manipulation of flood risk

Two successive manipulations were used. At first, after respondents entered the correct webpage, they were asked to answer a few personal questions. They were told that these questions served to see in which amount respondents were vulnerable to flood risks. After answering these questions, respondents were told that the computer processed the information and that they had to wait for a few seconds. At this point, the computer froze for 10 s, while the picture of a turning hourglass showed on the screen. Hereafter, respondents received the information about their personal risk of flooding in the future, based on their given answer. We employed a procedure similar to Rimal (2001) to manipulate risk perception and also efficacy as will be discussed later. Without actually calculating a score, randomly half of the participants received feedback that their personal risk in case of a flood was high, whereas the other half of the respondents were told that their personal risk in case of a flood was low, regardless of their answers to the personal questions.

Respondents in the high-risk group were given the following message:

Based on the information you provided, the chance that a future flood will have negative consequences for you—“is in the top 10% of the population living in an area prone to flooding.” This means that you are vulnerable when a flood will occur. While this assessment is not 100% accurate, it is highly reliable. Possibly you’re not worried about the possibility of a flood in the future, but did you know that the chance of flooding in the Netherlands is fairly high!

Respondents in the low-risk group were given the following message:

Based on the information you provided, the chance that a future flood will have negative consequences for you—“is in the bottom 10% of the population living in an area prone to flooding.” This means that you are not vulnerable when a flood will occur. While this assessment is not 100% accurate, it is highly reliable. Possibly, you didn’t worry about the possibility of a flood in the future, and this is legitimate. The chance of flooding in the Netherlands is fairly small!

Secondly, after respondents read this message, a fear appeal was used. After respondents had received their ‘personal risk message’, they were asked to read a newspaper article about flood risks in the Netherlands and the way in which citizens can prepare themselves for a possible flood in the future (this will be discussed in further detail below). This article was accompanied by a picture. Half of the participants received the newspaper article accompanied by a fear appeal picture, whereas the other half received the same article to which a more neutral picture was added (“Appendix”).

3.1.2 Manipulation of efficacy

After respondents received feedback about their personal flood risk, they were asked to read a newspaper article about flood risks in the Netherlands, as already discussed earlier. This article discussed in detail the precaution measures the government takes against flooding and the way in which citizens can prepare themselves for a possible flood in the future. Two different newspaper articles were established. Half of the respondents read the article that was established on the current campaign against flood risks (the ‘denk vooruit’ campaign) and was supposed to create lower levels of both self-efficacy and response efficacy. The other half read an article was in principle the same as the first article, but several sentences were added to increase the perceived levels of self-efficacy and response efficacy. Basically, these sentences were variations on ‘you can easily perform this’ (aimed at boosting self-efficacy beliefs), and ‘this behavior is successful in mitigating the threat’ (boosting response efficacy).

3.2 Participants

A total of 726 respondents between 18 and 85 years of age participated in the study. Responses were collected in two different waves. The first wave accounted for 160 participants and functioned as a pilot test to find support for the different manipulations. The second wave accounted for the other participants and took place 1 month later. Since no significant differences in dependent variable were found between both waves, results will be based on the total group of participants. Distribution of respondents among conditions varied between 156 and 238. Slightly more men (59%) than women (41%) participated in the study (χ² (1) = 24.00, p < 0.01).

3.3 Measures

After respondents finished reading the stimulus material, they were asked to fill in a questionnaire measuring the following variables. The questionnaire was based on a previously validated questionnaire (Ter Huurne 2008). This questionnaire, unless otherwise stated, measured responses on five-point Likert-type scales, with extremes strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

3.3.1 Actual information seeking

To measure the actual information seeking, respondents were asked, after reading the newspaper article, to choose between one of four Web site links with an informative name. Two of these links were relevant to the topic of flood risks, scoring 1 (the URL’s refer to the existing Dutch Web sites www.thinkahead.nl/emergencykit and www.netherlandsliveswithwater.nl/preparation). The other two Web site links were irrelevant to the topic, scoring 0 (the URL’s refer to www.traveldestinations.nl/Maledives and www.carweek.nl/Porsche911turbo). Respondents choosing the Web site links with the topic of flood risks showed adaptive actual information seeking, whereas respondents choosing one of the other Web site links did not (they showed maladaptive information seeking).

3.3.2 Intention to seek information

Furthermore, levels of intention to seek relevant risk information were measured using a 3-item scale. Respondents were asked to indicate how likely they were to seek information in the future and to keep track of relevant risk information. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.89, indicating that the inter-item correlations were consistently positive and high. This alpha >0.70 allowed us to aggregate the 3 items into one new variable ‘intention to seek information’.

3.3.3 Intention to take precautionary measures

The motivation of respondents to take preventive actions was measured using an 8-item scale. Respondents were asked how likely they were to take preparation and precautionary measures and adhere to given instructions. This scale was very reliable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94). Consequently, the 8 items were aggregated to a new variable ‘Intention to take precautionary measures’.

3.3.4 Risk perception

Risk perception was measured using a 17-item scale. Respondents were asked to indicate how severe and dangerous flood risks are, how high the chance is that a flood will occur in the Netherlands in the future, and how much damage a flood risk will cause for citizens living in the affected area. Also, they had to indicate how risky they felt flood risks are for them personally and how likely they felt it would be that a future flood would cause problems for them personally. Also, this scale yielded very reliable results (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94), and items were aggregated to the variable ‘risk perception’.

3.3.5 Self-efficacy

Level of self-efficacy was measured using a very reliable nine-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96). Respondents were asked to indicate to what extent they thought they could prepare themselves for the possibility of a flood risk in the future.

3.3.6 Response efficacy

Response efficacy was measured using a very reliable ten-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95), measuring the extent to which respondents thought that different preparation and precautionary measures were effective in protecting oneself from negative consequences of a possible flood in the future.

3.3.7 Efficacy scale

The analysis with regard to efficacy beliefs will be conducted based on the combination of levels of self-efficacy and response efficacy. The combined nineteen-item scale of both variables also showed to be highly reliable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.97), and items were aggregated to a new variable ‘efficacy beliefs’.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptive statistics

Analysis of variances indicated no differences between the four conditions in either gender (F(3,722) = 1.34, p = 0.26) or age (F(3,722) = 0.53, p = 0.66). The manipulation check revealed with a similar analysis significant main effects for risk perception, self-efficacy, and response efficacy, all in the predicted directions, that is, risk perception (F(1,722) = 97.69, p < 0.01, η² = 0.27); self-efficacy (F(1,722) = 51.50, p < 0.01, η² = 0.17); and response efficacy (F(1,722) = 45.08, p < 0.01, η² = 0.16). This indicates that the conditions differed on these variables as intended. Furthermore, no strong correlations between level of risk perception and self-efficacy (r = 0.15) or between risk perception and response efficacy (r = 0.15) were found, indicating that the manipulations were relatively independent and only enhanced the targeted variable, without increasing the levels of the other variables. Therefore, we can conclude that the manipulations were successful. A positive and highly significant correlation was found between self-efficacy and response efficacy (r = 0.84). This supported our goal to measure the effect of level of combined efficacy, and consequently, we combined the two factors for further analyses.

Table 2 presents the correlations of the dependent and independent variables with corresponding mean scores and standard deviations. Table 3 presents the mean scores for the separate conditions for all dependent variables.

4.2 Information seeking

Hypotheses 1a and 1b were tested using an ANOVA (analysis of variance). The effect of flood risk and efficacy beliefs manipulations on information seeking was measured. As can be seen in Table 2, significant main effects of flood risk (F(1,722) = 58.27, p < 0.01, η² = 0.08) and efficacy beliefs (F(1,722) = 22.74, p < 0.01, η² = 0.04) on actual information seeking were found. No interaction effect between the two variables existed (F(1,722) = 1.56, p = 0.22). With regard to the intention to seek relevant risk information, again we found significant effects of flood risk (F(1,722) = 37.29, p < 0.01, η² = 0.06) and efficacy beliefs (F(1,722) = 68.45, p < 0.01, η² = 0.11). Again, no interaction effect was found (F(1,722) = 0.61, p = 0.43).

Inspection of the mean scores in Table 3 learns that respondents in the high flood risk/high efficacy condition scored significantly higher on both actual information seeking (M = 0.96 indicates that 96% of the subjects choose the adaptive Web site link) and intention to seek information (M = 3.40) than the respondents in the other conditions. Furthermore, respondents in the low flood risk/low efficacy condition showed the least actual information seeking (M = 0.62, indicating that 62% of the subjects choose the adaptive Web site link, which is only slightly more that the 50% that would have been expected based on a random choice of the subjects) and intention to seek information (M = 2.35). This is in accordance with our hypotheses.

Furthermore, we looked at the relationship between actual information seeking and the intention to seek information to make sure that the intention to seek relevant risk information indeed corresponds with the actual behavior of citizens. Correlations were significant (r = 0.50) indicating that both concepts are related.

4.3 Intention to take risk-mitigating or preventive actions

With regard to the intention to take risk-mitigating or preventive actions, hypotheses 2a and 2b were tested with an analysis of variance. Results indicated significant main effects of both flood risk (F(1,722) = 31.21, p < 0.01, η² = 0.05) and efficacy beliefs (F(1,722) = 101.10, p < 0.01, η² = 0.13) on the intention to take self-protective measures. No interaction effect was found (F(1,722) = 0.29, p = 0.59).

Inspection of the mean scores in Table 3 indicates that respondents in the high flood risk/high efficacy condition showed significantly the most intention to take preventive actions (M = 3.86) compared with respondents in the other conditions, as expected. Respondents in the low flood risk/low efficacy condition showed a significantly lower intention to take preventive actions (M = 2.78) than in the other conditions. These results support our second set of hypotheses.

4.4 Relationship information seeking and intention to take preventive actions

With regard to the relationship between information seeking and the intention to take risk mitigating and preventive behavior, hypothesis 3 was formulated. Results show that the level of intended information seeking and the intention to take risk-mitigating or preventive actions correlated strongly and positively (r = 0.78). Furthermore, respondents showing actual information seeking by choosing the adaptive Web site link were significantly more willing to engage in risk-mitigating or preventive behaviors than respondents showing no actual risk information seeking (F(1,722) = 68.87, p < 0.01, η² = 0.03). These findings support the third hypothesis.

4.5 Mediation effect information seeking

A mediation analysis tested the hypothesis that actual information seeking mediates the relationship between risk perception and efficacy beliefs on the one hand and the intention of respondents to engage in self-protective behavior on the other hand (cf. Baron and Kenny 1986). The first regression analysis with the intention to take self-protective behavior as dependent variable and risk perception as the predictor yielded a significant relation (β = 0.45, p < 0.01). A second regression analysis, with the mediator (actual information seeking) as the dependent variable and risk perception as the predictor, showed that risk perception influenced actual information seeking significantly (β = 0.47, p < 0.01). Subsequently, following the procedure of Baron and Kenny (1986), a regression analysis with risk perception and actual information seeking as predictors and the intention to take self-protective behavior as the dependent revealed that the previously found relationship between risk perception and the intention to take self-protective behavior became less significant (β = 0.11, p < 0.05), whereas the mediator showed a highly significant relation (β = 0.73, p < 0.01), which indicated partial mediation of actual information seeking (Fig. 2). A Sobel test (Baron and Kenny 1986) confirmed that actual information seeking mediates the relation between risk perception and the intention of respondents to engage in self-protection (Z = 11.25, p < 0.01).

For efficacy beliefs as independent variable, the same analyses were conducted. The first regression analysis, with the intention to take self-protective behavior as dependent variable and efficacy beliefs as the predictor, yielded a significant relation (β = 0.71, p < 0.01). A second regression analysis, with the mediator (actual information seeking) as the dependent variable and efficacy beliefs as the predictor, showed that efficacy beliefs influenced actual information seeking significantly (β = 0.53, p < 0.01). The regression analysis with efficacy beliefs and actual information seeking as predictors and the intention to take self-protective behavior as the criterion revealed that the previously found relationship between efficacy beliefs and the intention to take self-protective behavior remained significant (β = 0.41, p < 0.01), whereas the mediator showed a highly significant relation (β = 0.56, p < 0.01), which indicated partial mediation of actual information seeking (Fig. 3). A Sobel test (Baron and Kenny 1986) confirmed that actual information seeking mediates the relation between risk perception and the intention of respondents to engage in self-protection (Z = 16.09, p < 0.01).

5 Discussion

This study contributes to the small body of literature available on the effect of risk perception and efficacy beliefs in the domain of risk communication and more in particular flood risk communication. This area is getting attention only recently (see e.g., Grothmann and Reusswig 2006; Zaalberg et al. 2009; Terpstra and Gutteling, 2008; Terpstra et al. 2009; Terpstra 2010). In our perspective, this study has scientific as well as societal or practical importance. It recognizes the need to enhance levels of risk perception and efficacy beliefs as well as the stimulation of individual active information seeking to increase the intention of citizens to adopt self-protective behaviors. The experiment with participants that actually live in flood-prone areas in the Netherlands indicates that flood risk communication can be effective in stimulating both information seeking and self-protective behavioral intentions. Results show that higher levels of induced risk perception and efficacy beliefs result in significantly higher levels of both information seeking and the intention to engage in self-protective behavior than lower levels. This is novel because, as far as we know, this has not been reported with respect to (flood) risk communication. The societal importance is related to the scarcity of evidence that individual flood self-protective behavior can be stimulated with relatively simple risk communication tools, which is important in the context of future climate change and sea level rising.

We also observe that respondents engaging in the gathering of relevant risk information are more intended to take preventive measures than low seekers. Furthermore, the seeking of information turned out to be a partial mediator between the independent variables risk perception and efficacy, and the intention to engage in preventive actions, indicating that enhancing information seeking might have positive impacts on the intention to take preventive actions among citizens. This too is a novel result. The study thus supports research efforts in the domain of risk information seeking (e.g., ter Huurne 2008), with the stimulation of self-protective behaviors in the population as a secondary goal. Therefore, the focus of flood risk communication research should not only be improving risk message effectiveness but it should also focus on the determinants of public risk information seeking. To date, only few studies have been reported on this topic, and many risk communication efforts aimed at stimulating self-protective behavior do not involve information-seeking processes. Therefore, additional research is needed here.

Based on previous risk information-seeking studies (ter Huurne 2008), one can assume that risk-awareness variables as risk perception (‘is there a threat?’), personal involvement (‘is the threat relevant to me?’), and self-efficacy (‘am I able to deal with the threat?’) are the triggers that can be used to stimulate the public’s motivation to seek risk information. In this experiment, we looked at risk perception and efficacy, assuming that personal involvement would be high because all of our participants lived in flood-prone areas. However, additional research must provide a better understanding of the role of personal involvement in this type of risk communication. Of course, governmental and other organizations can stimulate seeking risk information by providing the information by a multitude of channels and, e.g., to have it available 24/7 as is possible on the Internet.

However, the results of this study must be viewed in light of some limitations that need to be addressed. First of all, actual information-seeking behavior was measured using only one item. This seems not ideal in that the results of only one item can result in drawing biased conclusions about the information-seeking behavior among respondents. Therefore, using more items to measure information-seeking behavior seems advisable. Also, since our measure allowed respondents to make a rather effortless or costless choice, immediately after being confronted with the possibility to choose, this raises the question whether this type of response is representative of information-seeking processes outside an experimental reality. Additional research is needed here. Finally, taking preventive actions was measured by asking respondents about their intention to adopt recommendations. As the intention a person has to adopt certain behaviors does not always correspond to their actual behavior, this may give a slightly biased view of the preventive actions taken among respondents.

6 Conclusion

The results provide valuable implications for future risk communication efforts with respect to flood preparedness of the Dutch public and may have similar implications for other risk communication directed at preparative actions. First, to motivate the general public to engage in self-protective behavior, a certain level of risk awareness (or threat) is necessary in the communication effort to motivate receivers to actively engage in information seeking and to adopt self-protective recommendations. Furthermore, the results of this study suggest that risk messages aimed at promoting self-protective actions are effective under the conditions that the advised actions are perceived by the public as high on self-efficacy (Yes, you can do it) and high on response efficacy (Yes, it works). The preparation of such public service messages aimed at (flood) risk communication is thus of the utmost importance. The designers of these messages no longer can suffice to take their own perception of message effectiveness as the sole guideline. No, messages should be carefully crafted and designed along the lines of behavioral actions that are seen as efficacious by large numbers of people. Pretesting these message seems a must here, but most likely, the effort spend here will pay off at the end of the day.

References

Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Freeman, New York

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 6:1173–1182

Case DO, Andrews JE, Johnson DE, Allard SL (2005) Avoiding versus seeking: the relationship of information seeking to avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. J Med Libr As 93:353–362

De Wit MS, van der Most H, Gutteling JM, Bockarjova M (2008) Governance of flood risks in the Netherlands: interdisciplinary research into and meaning of risk perception. In: Martorell S et al (eds) Safety, reliability and risk analysis: theories, methods and applications. Taylor & Francis group, London, pp 1585–1593

Fink A, Ulbrich U, Engel H (1996) Aspects of the January 1995 flood in Germany. Weather 51:34–39

Griffin RJ, Neuwirth K, Dunwoody S (1999) Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviours. Environ Res 80:230–245

Griffin RJ, Yang Z, ter Huurne EFJ, Boerner F, Ortiz S, Dunwoody S (2008) After the flood: anger, attribution, and the seeking of information. Sci Commun 29:285–315

Grothmann T, Reusswig F (2006) People at risk of flooding: why some residents take precautionary action while others do not. Nat Hazards 38:101–120

Gutteling JM, Baan M, Kievik M, Stone K (2010) Risicocommunicatie in de ogen van de burger: ‘Geen paniek!’. In: van der Most H, de Wit S, Broekhans B, Roos W (eds) Kijk op waterveiligheid. Eburon, Delft

Kahlor LA (2007) An augmented risk information seeking model: the case of global warming. Media Psychol 10:414–435

Kievik M, Ter Huurne EFJ, Gutteling JM (2009) The action suited to the word. Use of the framework of risk information seeking to understand risk-related behaviors. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Risk Analysis, Baltimore, USA

Krasovskaia I (2005) Perception of flood hazard in countries of the north sea region of Europe (No. FLOWS WP2A–1). Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Oslo

Lindell MK, Perry RW (2000) Household adjustment to earthquake hazard: a review of research. Environment & Behavior 32:590–630

Maaskant B, Jonkman SN, Bouwer LM (2009) Future risk of flooding: an analysis of changes in potential loss of life in South Holland (the Netherlands). Environ Sci Policy 12:157–169

Miceli R, Sotgiu I, Settanni M (2007) Disaster preparedness and perception of flood risk: a study in an alpine valley in Italy. J Environ Psychol 28:164–173

Miller SM (1987) Monitoring and blunting: validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threat. J Pers Soc Psychol 52:345–353

Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Water Management. (2006) Kabinetsstandpunt Rampenbeheersing Overstromingen DGW/WV 2006/1306

Rimal RN (2001) Perceived risk and self efficacy as motivators: understanding Individuals’ long term use of health information. J Commun 51:634–654

Rimal RN, Real K (2003) Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change: use of the risk perception attitude (RPA) framework to understand health behaviors. Hum Commun Res 29:370–399

Sjoberg L (2002) Risk communication between experts and the public: perceptions and Intentions. Quest de Commun 2:19–35

Smith RA, Ferrara M, Witte K (2007) Social sides of health risks: stigma and collective efficacy. Health Commun 21:55–64

Ter Huurne EFJ (2008) Information seeking in a risky World. The theoretical and empirical development of FRIS: a framework of risk information seeking. Dissertation, University of Twente

Ter Huurne EFJ, Gutteling JM (2008) Information needs and risk perception as predictors of risk information seeking. J Risk Res 11:847–862

Terpstra T (2010) Flood preparedness. Thoughts, feelings and intentions of the Dutch public. Dissertation, University of Twente

Terpstra T, Gutteling JM (2008) Households’ perceived responsibilities in flood risk management in the Netherlands. Int J Water Resour 24:555–565

Terpstra T, Lindell MK, Gutteling JM (2009) Does communicating (flood) risk affect (flood) risk perceptions? Results of a quasi-experimental study. Risk Anal 29:1141–1155

Witte K (1992) Putting the fear back into fear appeals: the extended parallel process model. Commun Monogr 59:329–349

Witte K, Allen M (2000) A meta-analysis of fear appeals: implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behav 27:591–615

Zaalberg R, Midden C, Meijnders A, McCalley T (2009) Prevention, adaptation, and threat denial: flooding experiences in the Netherlands. Risk Anal 29:1759–1778

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Pictures manipulation

Appendix: Pictures manipulation

Fear appeal

No fear appeal

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kievik, M., Gutteling, J.M. Yes, we can: motivate Dutch citizens to engage in self-protective behavior with regard to flood risks. Nat Hazards 59, 1475–1490 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-011-9845-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-011-9845-1