Abstract

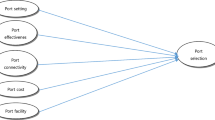

A novel Network-based Integrated Choice Evaluation (NICE) model is developed to enhance the multinomial logit preference (MNL) model that is widely employed in the existing port choice literature. The NICE model integrates the element of port service network with observational port attributes to identify important quality characteristics on which liner shipping companies base their port choices. An empirical study of the proposed model is conducted through the service schedules of three established liner shipping companies. Results show that port efficiency and scale economies are the more important dimensions influencing liner shipping companies’ selection of major Asian ports. Nevertheless, it is important for a competitive port to balance its efforts among all the dimensions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Lirn et al. (2003) have suggested that factor analysis would provide an alternative approach to narrow down the number of port attributes and improve the methodology of their paper.

By defining the set in terms origin–destination (O–D) pairs served by a port, our model is able to include transshipment routes in addition to direct shipping between point of supply and point of demand. If we define the sets as simply nodes served by a port, such treatment considers only the case of direct shipping (starting or ending at the port) and ignores the possibility of transshipment. Much of the existing port literature has documented that immense competitive pressure arises as each port seeks to attract transshipment traffic. The omission of transshipment route will lead to an under-estimation of the connectivity index, which can be easily verified through numerical computations.

This extra node is needed to account for the possibility of a direct shipping route starting from a common node and ending at the port itself (or vice versa) without going further to other exclusive nodes from port.

As an illustration, in the consolidated network depicted in Fig. 3, the Singapore and Hong Kong ports serve seven and three destinations respectively. Of these destinations, China is a common destination. (i.e., n SIN,HKG = 1). It follows that, including the port itself, n SIN = 7and n HKG = 3. Using the formulas in “Section 2.1”, a total of 48 O–D pairs are obtained.

The proximity of these supporting infrastructures (not included in this study) could be more important.

The total trade volume in a country comes from domestic imports and exports as well as transshipment. Ports located in centrality serve rich hinterland and benefit from larger domestic trade volume while those located in intermediacy at the intersection of major trading axes are able to capture additional transit cargo traffic to augment existing volume in home country.

Normalization is done such that the best performing port in the category is given the highest score of ten points. For example, the port with the deepest draught will score 10. The score for other ports are computed using the formula: (Depth of draught at port) divide by (Deepest draught of ports in sample) and multiply by 10. When dealing with ship turnaround time and port charges, a little more care is required to retain such scoring scheme. Ports with the lowest figures will be given the highest score of 10 and other ports are scored against the benchmark set by the best performing ports. In this way, we prevent the offsetting effect which will otherwise occur (for example, long turnaround time versus low port charges)

The factor scores for each individual port in Table 5 are estimated from [ξ 1 ξ 2 ... ξ c] = XR -1 A c where R is the sample correlation matrix.

While the main purpose of standardization (i.e., dividing the score in each observation by score of the best performer in the same dimension) is to avoid dominance of measures with bigger figures, we also convert the negative scores into positive ones for ease of interpretation.

The Ports of Kaohsiung and Jawaharlal Nehru are omitted in the Multiple Logistic regression analysis due to the unavailability of information on the ship turnaround time.

One of the most obvious factors determining a port’s ability to attract transshipment traffic is the geographical location of the port. Ports located in proximity to major trading axes, such as Singapore, Hong Kong and Kaohsiung, attract transshipment traffic (Sutcliffe and Ratcliffe 1995). Physical location also affects connectivity through its impact on the marginal cost of stopping at a port. As an example, for a voyage originating from Singapore heading towards Yokohama, the Hong Kong and Shanghai ports present lower marginal cost compared to the Busan port.

References

Baird AJ (1996) Containerisation and the decline of upstream urban ports in Europe. Marit Policy Manage 23(2):145–156. doi:10.1080/03088839600000071

Blonigen BA, Wilson W (2006) New measures of port efficiency using international trade data. NBER working paper no. 12052

Cullinane KPB, Khanna M (1999) Economies of scale in large container ships. J Transp Econ Policy 33(2):185–208

D’ Este GM, Meyric S (1992) Carrier selection in a RO/RO ferry trade: part 1. Decision factors and attitudes. Marit Policy Manage 19(2):115–126

Gilman S (1999) The size economies and network efficiency of larger container ships. Int J Marit Econ 1(1):39–59

Gilman S, Williams GE (1976) The economics of multi-port itineraries for large container Ships. J Transp Econ Policy 10(2):137–149

Hansen WG (1959) How accessibility shapes land use. J Am Inst Plann 25:73–76

Hayuth Y (1991) Load centering competition and modal integration. Coast Manage 19(3):297–311

Hayuth Y, Fleming DK (1994) Concepts of strategic commercial location: the case of container ports. Marit Policy Manage 21(3):187–193

International Institute for Management Development (2006) World competitiveness yearbook. International Institute for Management Development, Lausanne

Lattin J, Carroll DJ, Green PE (2003) Analyzing multivariate data. Duxbury applied series. Thomson Brooks, Belmont, pp 127–166

Lloyd’s Registered Fairplay (2007) Ports guide. Available via http://www.portguide.com/. Accessed between 07 March 2007 to 13 March 2007

Lee LH, Chew EP, Lee LS (2006) Multicommodity network flow model for Asia’s container ports. Marit Policy Manage 33(4):387–402

Lee SW, Song DW, Ducruet C (2008) A tale of Asia’s world ports: the spatial evolution in global hub port cities. Geoforum 39:372–385

Lirn TC, Thanopoulou HA, Beresford AKC (2003) Transshipment port selection and decision-making behavior: analysing the Taiwanese Case. Int J Logist Res Appl 6(4):229–244

Lirn TC, Thanopoulou HA, Beynon MJ, Beresford AKC (2004) An application of AHP on transshipment port selection: a global perspective. Marit Econ Logist 6:70–91

Malchow M, Kanafani A (2004) A disaggregate analysis of port selection. Trans Res Part E 40(4):317–337

Min H, Guo Z (2004) The location of hub-seaports in the global supply chain network using a cooperative competition strategy. Int J Integr Supply Chain 1(1):51–63

Murphy PR, Daley JM (1994) A comparative analysis of port selection factors. Trans J 34:15–21

National Magazine Co. (2006) Containerisation international yearbook. National Magazine Co., London

Nir AS, Lin K, Liang GS (2003) Port choice behavior—from the perspective of the shipper. Marit Policy Manage 30(2):165–173

Notteboom T, Winkelmans W (2001) Structural changes in logistics: how will port authorities face the challenges. Marit Policy Manage 28:71–89

Parola F, Musso E (2007) Market structures and competitive strategies: the carrier-stevedore arm-wrestling in northern European ports. Marit Policy Manage 34(3):259–278

Polo G, Diaz D (2006) A new generation of containerships: cause or effect of the economic development? J Marit Res 3(2):3–18

Porter ME (1980) Competitive strategy. Free Press, New York, p 41

Talley W (2006) An economic theory of the port. In: Cullinane K, Talley WK (eds) Research in transportation economics: port economics. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Taylor MAP, Sekhar SVC, D’Este GM (2006) Application of accessibility based methods for vulnerability analysis of strategic road networks. Netwo Spat Econ 6:267–291

Tiwari P, Itoh H, Doi M (2003) Shippers’ port and carrier selection behaviour in China: a discrete choice analysis. Marit Econ Logist 5:23–39

Tongzon JL (1995) Determinants of port performances and efficiency. Trans Res Part A 29(3):245–252

Sanchez RJ, Hoffmann J, Micco A, Pizzolitto GV, Sgut M, Wilmsmeilier G (2003) Port efficiency and international trade: port efficiency as a determinant of maritime transport costs. Marit Econ Logist 5:199–218

Schoner B, Wedley WC (1989) Ambiguous criteria weights in AHP: consequences and solutions. Decis Sci 20(3):462–475

Slack B (1985) Containerization, inter-port competition and port selection. Marit Policy Manage 12(4):293–303

Slack B (1993) Pawns in the game: ports in a global transportation system. Growth Change 24:579–588

Song DW, Yeo KT (2004) A competitive analysis of Chinese container ports using the analytical hierarchy process. Marit Econ Logist 6:34–52

Sutcliffe P, Ratcliffe B (1995) The battle for med hub role. Contain Int 28(7):95–99

Walter CK, Poist PF (2003) Desired attributes of an inland port: shipper vs carrier perspective. Trans J 42(5):42–55

Wang M (2005) The rise of container transport in East Asia. In: Lee TW, Cullinane K (eds) World shipping and port development. Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, pp 10–33

Wang TF, Cullinane KPB (2006a) The efficiency of European container terminals and implications for supply chain management. Marit Econ Logist 8:82–99

Wang Y, Cullinane KPB (2006b) Inter-port competition and measures of individual container port accessibility. Unpublished paper, University of Newcastle upon Tyne

Wilmsmerier G, Hoffman J, Sanchez RJ (2006) The impact of port characteristics on international maritime transport cost. Res Trans Econ 16:117–140

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their thanks to the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments to improve the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, L.C., Low, J.M.W. & Lam, S.W. Understanding Port Choice Behavior—A Network Perspective. Netw Spat Econ 11, 65–82 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11067-008-9081-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11067-008-9081-8