Abstract

Question

Do prophylactic anticonvulsants decrease the risk of seizure in patients with metastatic brain tumors compared with no treatment?

Target population

These recommendations apply to adults with solid brain metastases who have not experienced a seizure due to their metastatic brain disease.

Recommendation

Level 3 For adults with brain metastases who have not experienced a seizure due to their metastatic brain disease, routine prophylactic use of anticonvulsants is not recommended.

Only a single underpowered randomized controlled trial (RCT), which did not detect a difference in seizure occurrence, provides evidence for decision-making purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Rationale

Brain metastases are a common complication of systemic cancer, occurring in approximately 20–40% of patients. Since an intracranial mass lesion may predispose patients to seizure, the question has arisen as to whether prophylactic use of anticonvulsants may prevent seizures in this population. Previously published guidelines on this topic have included patients with both primary and secondary brain tumors [1, 2].

The objective of this guideline paper is to specifically address the role of anticonvulsant prophylaxis in adults with solid metastases to the brain. The rationale for this is that intracranial metastases from systemic cancer tend to be spherical and more contained when compared to primary brain tumors which are more infiltrative in nature. Given this difference in typical growth patterns, it is conventionally thought that brain metastases may be less likely to induce seizures than primary tumors.

Methods

Search strategy

The following electronic databases were searched from 1990 to September 2008: MEDLINE®, Embase®, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry, Cochrane Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects. A broad search strategy using a combination of subheadings and text words was employed. The search strategy is documented in the methodology paper for this guideline series by Robinson et al. [3] Reference lists of included studies were also reviewed.

Eligibility criteria

For inclusion in this systematic review the following criteria needed to be met:

-

Published in English with a publication date of 1990 forward.

-

Patients with brain metastases.

-

Fully-published peer-reviewed primary comparative studies (all comparative study designs for primary data collection included; e.g., RCT, non-randomized trials, cohort studies or case–control studies).

-

Study comparisons include the following:

-

anticonvulsant prophylaxis vs. none

-

Number of study participants with brain metastases ≥ 5 per study arm for at least two of the study arms.

-

Baseline information on study participants is provided by treatment group in studies evaluating interventions exclusively in patients with brain metastases. For studies with mixed populations (i.e., includes participants with conditions other than brain metastases), baseline information is provided for the intervention sub-groups of participants with brain metastases.

Study selection and quality assessment

Two independent reviewers evaluated citations using a priori criteria for relevance and documented decisions in standardized forms. Cases of disagreement were resolved by a third reviewer. The same methodology was used for full text screening of potentially relevant papers. Studies which met the eligibility criteria were data extracted by one reviewer and the extracted information was checked by a second reviewer. The PEDro scale [4, 5] was used to rate the quality of randomized trials. The quality of comparative studies using non-randomized designs was evaluated using eight items selected and modified from existing scales.

Evidence classification and recommendation levels

Both the quality of the evidence and the strength of the recommendations were graded according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS)/Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) criteria. These criteria are provided in the methodology paper for this guideline series.

Guideline development process

The AANS/CNS convened a multi-disciplinary panel of clinical experts to develop a series of practice guidelines on the management of brain metastases based on a systematic review of the literature conducted in collaboration with methodologists at the McMaster University Evidence-based Practice Center.

Scientific foundation

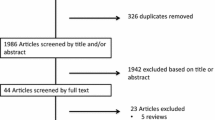

The literature search resulted in the identification of 16,966 citations of which 16,962 were eliminated at abstract review as not having relevance to the specific question. The remaining four studies were subject to full text screening, three of which were excluded because they lacked baseline patient data for brain metastases sub-group. Only one study [6] met the eligibility criteria and forms the basis of this report (see Fig. 1).

Clearly, the role of anticonvulsant use specifically in the management of brain metastases has been explored in a very limited number of controlled comparative trials, and therefore the class of evidence and hence the recommendations have limited applicability. Table 1 summarizes the only applicable study, in terms of class of evidence.

This study, by Forsyth et al. [6], is an RCT of anticonvulsants versus no anticonvulsants in 100 patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors (diagnosis <1 month from study entry). Patients were stratified for primary (n = 40) or metastatic (n = 60) pathology. Additional eligibility criteria were adequate hepatic, bone marrow and renal function. Excluded were patients with limited life expectancy (<4 weeks), known prior seizures, anticonvulsant allergy, substance abuse and pregnancy. Of patients with brain metastasis, 26 were treated with anticonvulsants, usually phenytoin (n = 25) or phenobarbital (n = 1) using oral loading and conventional maintenance dosing; 34 patients received no anticonvulsants. The primary outcome reported was seizure occurrence at 3 months post-randomization.

The trial was terminated early because the seizure rate in the no anticonvulsant arm was only 10%, which put the anticipated seizure rate of 20% outside the 95% confidence interval. In addition, mortality prior to the 3-month follow-up was much higher than anticipated (observed 30% vs. projected 15%). The authors of the trial noted that the combination of these two factors indicated that the power to detect a clinically important difference in seizure occurrence between the two groups would be less than 20% based on the planned-for accrual of 300 patients.

The only outcome reported specifically for the sub-group of patients with brain metastases was seizure incidence, and there was no significant difference between those who received anticonvulsant prophylaxis and those who did not (log rank test; P = 0.90).

Conclusions and discussion

It is very difficult to make recommendations regarding the role of anticonvulsant prophylaxis in patients with brain metastases based on sub-group data from one underpowered randomized trial. All of the studies evaluating prophylactic anticonvulsant use identified by this systematic review included patients with both primary and secondary tumors. Only one of these trials stratified by metastases versus primary pathology and presented baseline data for the brain metastases sub-group and, therefore, met the eligibility criteria for this systematic review.

Given the premise that brain metastases are probably less likely than primary brain tumors to cause seizures, it is noteworthy that previously published guidelines on the role of anticonvulsants in patients with brain tumors (either primary or secondary) have recommended against their prophylactic use [1, 2]. Although only the single aforementioned study met our search criteria, the rationale for making a Level 3 recommendation not to use routine prophylactic anticonvulsants is further explained by the fact that anticonvulsant use can have significant adverse effects, and by the lack of evidence suggesting any benefit from the prophylactic use of anticonvulsants for patients with brain metastases. The key conclusion from these guidelines, then, is that there is a lack of a clear and robust benefit from the routine prophylactic use of anticonvulsants.

Key issues for future investigation

Given the ubiquity of anticonvulsant use for prophylactic and active treatment of seizures associated with metastatic brain disease, the medical literature contains relatively few detailed reports specifically addressing their use. Future studies could be planned to allow better control, recording and analysis of anticonvulsant dosing and response to allow a more robust analysis of the risk to benefit ratio of various agents. A host of newer anticonvulsants are now available and in widespread use [7]. These often have a better safety profile than older agents and lower likelihood for significant drug interactions. Although patients with metastatic carcinoma may be prone to seizure, prophylactic anticonvulsant use is not recommended. Once a seizure has occurred, however, anticonvulsants are safe and effective, especially the newer agents. Unresolved questions which could be the subject of prospective studies include the prognosis for patients with a single peri-operative seizure versus multiple symptomatic seizures, with regards to long-term control, adverse effects of therapy and safety.

No ongoing or recently closed clinical trials on the prophylactic use of anticonvulsants for the management of brain metastases were found that met the eligibility criteria.

References

Perry J, Zinman L, Chambers A, Spithoff K, Lloyd N, Laperriere N (2006) The use of prophylactic anticonvulsants in patients with brain tumours—a systematic review. Curr Oncol 13(6):222–229

Glantz MJ, Cole BF, Forsyth PA, Recht LD, Wen PY, Chamberlain MC et al (2000) Practice parameter: anticonvulsant prophylaxis in patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 54(10):1886–1893

Robinson PD, Kalkanis SN, Linskey ME, Santaguida PL (2009) Methodology used to develop the AANS/CNS management of brain metastases evidence-based clinical practice parameter guidelines. J Neurooncol. doi:10.1007/s11060-009-0059-2

Centre for Evidence-Based Physiotherapy (2009) Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). http://www.pedro.org.au/. Last Accessed in Jan 2009

Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Moseley AM, Elkins M (2003) Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther 83(8):713–721

Forsyth PA, Weaver S, Fulton D, Brasher PM, Sutherland G, Stewart D et al (2003) Prophylactic anticonvulsants in patients with brain tumour. Can J Neurol Sci 30(2):106–112

Vajda FJ (2000) New antiepileptic drugs. J Clin Neurosci 7(2):88–101

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the McMaster Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC), Dr. Parminder Raina, (Director). Dr. Lina Santaguida (Co-Associate Director, Senior Scientist) led the EPC staff, which was responsible for managing the systematic review process, searching for and retrieving, reviewing, data abstraction of all articles, preparation of the tables and the formatting and editing of the final manuscripts.

Disclaimer of liability

The information in these guidelines reflects the current state of knowledge at the time of completion. The presentations are designed to provide an accurate review of the subject matter covered. These guidelines are disseminated with the understanding that the recommendations by the authors and consultants who have collaborated in their development are not meant to replace the individualized care and treatment advice from a patient’s physician(s). If medical advice or assistance is required, the services of a competent physician should be sought. The proposals contained in these guidelines may not be suitable for use in all circumstances. The choice to implement any particular recommendation contained in these guidelines must be made by a managing physician in light of the situation in each particular patient and on the basis of existing resources.

Disclosures

All panel members provided full disclosure of conflicts of interest, if any, prior to establishing the recommendations contained within these guidelines.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mikkelsen, T., Paleologos, N.A., Robinson, P.D. et al. The role of prophylactic anticonvulsants in the management of brain metastases: a systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Neurooncol 96, 97–102 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-009-0056-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-009-0056-5