Abstract

In the Dravidian languages, finite clauses cannot be coordinated, relative clauses cannot be finite, and relative clauses cannot be coordinated. I offer an explanation of these facts by making a typological claim about the Dravidian clausal left periphery: apart from a high ForceP, there is only one position in this domain. The coordination marker, the relativizer, and the elements that instantiate Mood—Mood being the realization of finiteness in Dravidian—must compete for this position.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

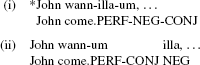

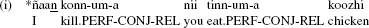

We illustrate only conjunction, but what we say about conjunction here is equally applicable to disjunction. The question particle -oo, which is homophonous with the disjunction marker, can be used in a finite clause, as we show later.

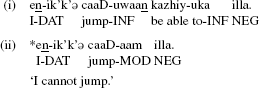

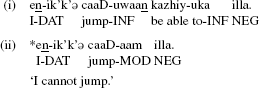

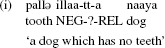

I am distinguishing ‘true’ modals, which belong to the syntactic class of ‘modal’, from verbal expressions which only have a modal meaning. In English, we can distinguish ‘can’ from ‘be able to’ (signifying ability), or ‘will’ from ‘be going to’ (signifying future eventuality). In Malayalam, -aam (a verbal suffix) is a true modal, signifying possibility/permission/ability; whereas kazhiy- ‘be able to’ is not a modal at all. The latter, but not the former, can occur as the complement of the finite negative element illa (see Sect. 5):

The future marker -um is a modal in Malayalam (Hany-Babu 1997).

A weaker claim would be that tense and aspect morphemes are homophonous in some cases, and that in contexts where ‘tense’ morphemes seem to appear in nonfinite verb forms, what we actually see are aspect morphemes. While such a solution will serve the case of conjunct verbs, it is insufficient to deal with the facts of Kannada negation. See also fn. 7. But let me also note that the issue of whether Dravidian has Tense or not is not crucial for us; what is crucial is the claim that finiteness is constituted by MoodP.

Recall that there is an agreement matrix on Tense in English in the indicative mood. Could this agreement matrix actually be on the head of MoodP, and not TP, even in English (as suggested by A & J:216–217, n. 21)? In other words, could the AgrP above TP of early minimalism actually be the MoodP?

Would there be any point in postulating an abstract TenseP in Dravidian, to bring it in line with the functional sequence of European clause structure? The question is discussed in A & J. One will have to say that its head, T0, is phonologically null, but can be marked for the feature [+Past/−Past]. But note that since the tense interpretation will be determined entirely by the perfective/imperfective—i.e., aspectual—choice (see A & J for details), T0 will in effect make no semantic contribution; or in other words, it will be doing no work. A & J also point out that a null functional head which is optionally marked for opposite values—[+Past/−Past]—may constitute a learning problem.

In fact, Anandan (1993) suggested that the coordination markers of Malayalam select only [-V] categories. This suggestion would of course have an immediate problem with the coordination of infinitival verb forms like in (3a)—unless one can maintain that infinitivals are nominal. See also fn. 15.

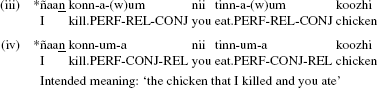

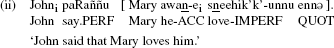

Changing the order of relativizer and conjunction marker does not ‘save’ the sentence:

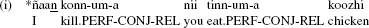

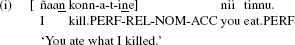

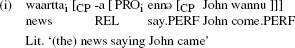

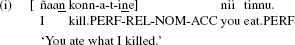

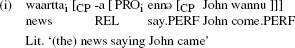

See Jayaseelan and Amritavalli (2005) for an account of the nominalization of relative clauses in Dravidian. Typical examples of this are free relatives; cf. (i). Note that the nominalized relative clause is case-marked.

Whether Dravidian has Adjective as a lexical category is a much-debated question. See Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2003) for a discussion of this question.

See A & J, Sect. 4 for a fuller treatment of illa.

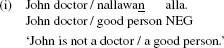

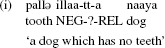

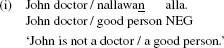

The language also has a copula of predication—commonly called the ‘equative’ copula—aaNə; it is negated by alla, cf. (i):

Since alla has all the properties of illa, we will not give it a separate treatment.

The negation of modals in Dravidian is a complicated question, which we will not go into here. See Hany-Babu (1997) for a preliminary discussion.

The head of MoodP that it incorporates is the head of indicative mood which is null.

Actually, A & J distinguish three illas in Dravidian, only two of which incorporate Mood. The third illa (their illa 3) incorporates an existential verbal root and negation, and stays well within IP. (We illustrate this illa presently.)

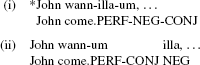

One might ask: what accounts for the grammaticality contrast between (21) and (22c)? (Their first conjuncts are repeated below.) Superficially, they show just a change of order between -um and illa.

The answer must be that the -um in (ii) is not in the C domain, but is generated in a lower position. I suggest that it is generated above the Aspect Phrase that hosts the perfective aspect. (The -um in (22a) and (22b) also must be in a lower position than the C domain.) But in (i), -um does not have that option, because it is above illa which is in the C domain. And the ‘narrow C domain’ of Dravidian cannot accommodate both these elements (as we argue below).

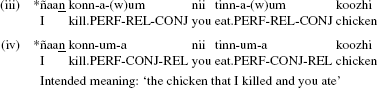

But why doesn’t a similar change of order between -um and -a rescue sentence (10), as was shown in fn. 10? We repeat the relevant sentences below as (iii) and (iv):

In (iv), if -um is generated above Aspect Phrase, it should not prevent the generation of -a in the C domain. The only solution I have at present is a morphological restriction: -a apparently needs to be directly affixed to an aspect head without any intervener; whereas illa, by contrast, is an independent word.

For some reason, negation by -aa is possible only when the verb is not a copula. If the relative clause is a copular clause, its negation is done by using illa 3, the nonfinite illa (see fn. 20); cf. (i):

Since this illa stays within IP, it does not ‘interfere’ with the appearance of the relativizer -a in C.

Since agreement is a reflex of indicative mood, and indicative mood and ‘true’ modals are in complementary distribution universally, the non-co-occurrence of Agreement and Modal is not surprising. What is peculiar to Dravidian is that Neg incorporates Mood.

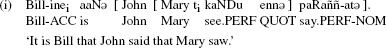

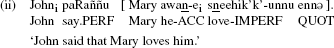

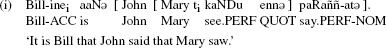

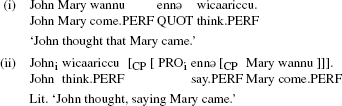

We need to note that ennə clauses also show some complement-like behavior. Thus they allow subextraction in the cleft construction (as shown at length in Jayaseelan and Amritavalli (2005)):

Also, pronominals in the ennə clause can be like in indirect speech:

The traditional analysis of ennə is that it is a ‘say’-verb which has been grammaticalized as a complementizer. But a complementizer needs a clause as its complement. In (28), or in the sentences of (31) (below), ennə does not have a clausal complement, just an NP complement.

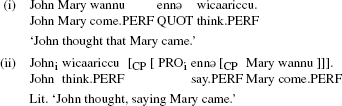

The analysis I am suggesting will give the sentence (i) the underlying structure shown in (ii).

Kaynean ‘roll-up’ (Kayne 1994), which moves the object argument to the left of the verb, will give us the surface word order. The point to note is that ‘ennə + object argument’ is itself a CP—more specifically, a nonfinite adjunct CP.

The structure of (30b) would be (i) (abstracting away from roll-up movements):

The Malayalam data lend support to Kayne’s (2010) claim that the category Noun does not project, and that all the elements which have traditionally been analyzed as nominal complements are relativization structures. If relativization structures are necessarily clausal, the Malayalam data support that claim too: a Malayalam noun takes either a straightforward relative clause, or an ‘ennə + -a’ structure—and we claimed that ennə together with its object argument is a CP.

A reviewer queries: are we saying that the Tense head still exists in C, but is collapsed with the Mood head? Or are we saying that in Dravidian, Tense is truly missing?

An answer to this question is already touched on in fn. 7. We can add the following: In languages which clearly have a Tense head, two functions are usually attributed to Tense, namely anchoring (which is the same as finiteness) and temporal interpretation. In Dravidian, temporal interpretation is completely determined by Aspect. And finiteness is dependent on the presence of Mood. Therefore it is difficult to imagine what function an ‘implicit’ Tense in C can have in Dravidian. The fact is that Tense is never projected in Dravidian. What happens to a feature of C—e.g., Focus—when it is not projected? It is simply not there!

The conditional clause is nonfinite as can be determined by our tests. Therefore -um is taking a nonfinite complement here, as we should now expect.

But there was a historical stage of English in which or was used as a question particle, a fact which argues that it was then a disjunction operator generated in ForceP; see Jayaseelan (2012).

In this function, it of course does not have the option of being generated in ForceP, for this would yield the wrong semantics. There is a residual question—why should it be generated in an operator position when it is not an operator but only a coordination marker? I have no good answer to this at present.

I wish to thank Miyamoto Yoichi for kindly providing the data, and for discussing the data.

About this marker, M. Yoichi says: “some people translate it as ‘and’; but I am not sure that is really the case.”

References

Amritavalli, R. 2003. Question and negative polarity in the disjunction phrase. Syntax 6(1): 1–18.

Amritavalli, R., and K. A. Jayaseelan. 2003. The genesis of syntactic categories and parametric variation. In Proceedings of the 4th GLOW in Asia 2003: Generative grammar in a broader perspective, ed. Hang-Jin Yoon, 19–41. The Korean Generative Grammar Circle.

Amritavalli, R., and K. A. Jayaseelan. 2005. Finiteness and negation in Dravidian. In The Oxford handbook of comparative syntax, eds. Guglielmo Cinque and Richard Kayne, 178–220. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anandan, K. N. 1985. Predicate nominals in English and Malayalam. M.Phil. dissertation, CIEFL, Hyderabad.

Anandan, K. N. 1993. Constraints on extraction from coordinate structures in English and Malayalam: An ECP approach. Ph.D. dissertation, CIEFL, Hyderabad.

Chomsky, Noam. 2004. Beyond explanatory adequacy. In Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures, ed. Adriana Belletti. Vol. 3, 104–131. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta, 133–166. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2009. Five notes on correlatives. In Universals and variation: Proceedings of GLOW in Asia VII, 2009, eds. Rajat Mohanty and Mythili Menon, 1–20. Hyderabad: The EFL University Press.

Hany-Babu, M. T. 1997. The syntax of functional categories. Ph.D. dissertation, CIEFL, Hyderabad.

Haraguchi, Tomoko, and Yuji Shuhama. 2011. On the cartography of modality in Japanese. Poster presented at GLOW in Asia workshop for young scholars, Mie University, Japan, 7–8 September 2011.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2001. Questions and question-word incorporating quantifiers in Malayalam. Syntax 4(2): 63–93.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2004. The serial verb construction in Malayalam. In Clause structure in South Asian languages, eds. Veneeta Dayal and Anoop Mahajan, 67–91. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2010. Stacking, stranding, and pied-piping: A proposal about word order. Syntax 13(4): 298–330.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2011. Comparative morphology of quantifiers. Lingua 121(2): 269–286.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2012. Question particles and disjunction. Linguistic Analysis 38(1–2): 35–51.

Jayaseelan, K. A., and R. Amritavalli. 2005. Scrambling in the cleft construction in Dravidian. In The free word order phenomenon: Its syntactic sources and diversity, eds. Joachim Sabel and Mamoru Saito, 137–161. New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kayne, Richard. 2010. Antisymmetry and the lexicon. In Comparisons and contrasts, 165–189. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keenan, Edward L. 1985. Relative clauses. In Complex constructions. Vol. 2 of Language typology and syntactic description, ed. Timothy Shopen, 141–170. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Murasugi, Keiko. 1991. Noun phrases in Japanese and English: A study in syntax: Learnablility and acquisition. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Connecticut.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1997. Notes on clause structure. In Elements of grammar: Handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 237–279. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Richards, Marc. 2007. On feature inheritance: An argument from the phase impenetrability condition. Linguistic Inquiry 38(3): 563–572.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar: Handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Sridhar, S. N. 1990. Kannada. London: Routledge.

Starke, Michal. 2009. Nanosyntax: A short primer to a new approach to language. In Nordlyd 36.1, special issue on nanosyntax, eds. Peter Svenonius, Gillian Ramchand, Michal Starke, and Knut Tarald Taraldsen, 1–6. Tromsø: CASTL. http://www.ub.uit.no/baser/nordlyd/.

Steever, Sanford B. 1988. The serial verb formation in the Dravidian languages. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Stowell, Timothy. 1982. The tense of infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry 13: 561–570.

Vergnaud, Jean-Roger. 1974. French relative clauses. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at LISSIM-V at Kangra (Himachal Pradesh, India) (May 2011), at a conference on Finiteness in South Asian Languages at the University of Tromsø (June 2011), and at a conference on Syntactic Cartography at the University of Geneva (June 2012). I wish to thank the audiences at the three venues for helpful feedback. Thanks to R. Amritavalli for discussions and comments during the writing of the paper. And I am thankful to Rajesh Bhatt, the official commentator for this paper for this volume, for the very insightful comments and feedback he provided, which have been of very great help to me.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jayaseelan, K.A. Coordination, relativization and finiteness in Dravidian. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 32, 191–211 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9222-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9222-8