Abstract

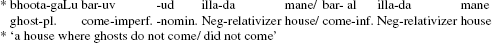

Finiteness cannot be identified with Tense. What is currently understood as Tense must be seen as a complex of features with two functions: event anchoring or finiteness, and temporality and tense interpretation; these features need not always occur together on one element. Finite negative clauses in Dravidian languages are matrix non-finite complements to a negative element. The non-finite clause can have a tense interpretation, but the constructs ‘selected tense’ or ‘dependent tense’ (Landau 2004) appear to be irrelevant to it. Finite negative clauses seem rather to separate tense interpretation and clausal anchoring. Dravidian anchors the clause to the world of the utterance by virtue of Mood: the anchors are a finite neg element, agreement, and modals. Neg and agreement select different verbal complements, in accordance with their polarity; consequently, affirmative and negative clauses look superficially very different.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In (3a), the watching goes on until the prisoners have died, and in (3b), the marching goes on until the marchers complete entering the mess hall; i.e., the events described in the embedded clauses are completed.

Lin (2006) modifies the rule for the interpretation of perfective aspect, to indicate past time.

Subsequently, Ritter and Wiltschko (2009) have analyzed these clauses as non-finite nominalized clauses that disallow location anchoring, and have possessive morphology as subject agreement. They now characterize the contexts where Halkomelem does not allow location marking as precisely those where English does not allow tense marking.

Observing that “the strongest piece of evidence” for this distinction in Chinese is the distribution of PRO and lexical subjects, Lin refers to alternative analyses that do not appeal to finiteness. Lexical subjects occur in control contexts where an adverbial intervenes between the matrix verb and embedded subject. This suggests that the absence of lexical subjects in these same contexts may be due to the Obviation Principle. Control into the possessor position of body-related nouns (‘tears’, ‘breast milk’) suggests the possibility of a semantic/pragmatic account of control into verb complements as well.

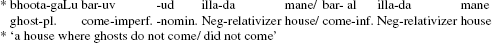

Non-finite negation appears on the stem of the verb, and is followed by an augment. Infinitive morphology does not appear on the negated verb, but on a dummy verb ‘be’.

The finite complementizer has the cognate forms ani, annɨ and ennə in Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam, sister Dravidian languages with a literary tradition (hence the nomenclature “major” Dravidian languages). The Dravidian finite complementizer is often referred to as the “quotative.”

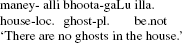

The proposal to specify neg illa with a covert tense feature in effect treats it as a “higher predicate” that selects a verbal complement. Our argument against it is consistent with evidence that neg illa is distinct from a negative existential predicate illa, illustrated in (i):

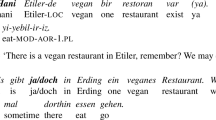

-

(i)

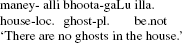

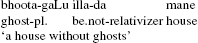

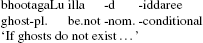

Negative existential illa has non-finite relative and conditional forms:

-

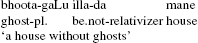

(ii)

-

(iii)

Neg illa has no non-finite forms.

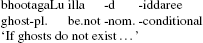

-

(iv)

-

(v)

These facts were first noted by Hany Babu (1996) for Malayalam.

-

(i)

Ritter and Wiltschko’s (2009) Parametric Substantiation Hypothesis allows functional categories not to be uniquely associated with the same substantive content across languages (INFL in English is INFLTENSE, in Halkomelem INFLLOCATION, and in Blackfoot INFLPERSON). It does not envisage multiple exponence of a functional category within a language. Note that these authors do not address the question of the finiteness of modals in English, i.e., the occurrence of INFLMODAL. This oversight also explains their belief that “the presence of an obligatory contrast of some sort” in INFL (i.e., a binary contrast of tense, location or person) is necessary for anchoring.

Krifka contends that NPs based on some are not polarity items. He attributes the scope differences of not … anyone, not … someone to “a paradigmatic effect induced by Grice’s principle of ambiguity avoidance” (the unambiguous form with anyone would be preferred for the wide-scope reading of not). But he concedes that “it may … be that this paradigmatic effect is so strong that it is virtually grammaticalized.”

This context “neutralizes” the gerund and the infinitive into a single non-finite category.

In speech, ille is often realized as le. Emphatic markers -ee or -ũũ on the verb may render ille more perspicuous: vara(v)-ee (i)lle, vara-(v)-ũũ ille.

Data such as (15)–(16) explain the Dravidianist Schiffman’s (1974) call for “an evaluation procedure to help ascertain when two sentences are equivalent except for one being positive, the other negative,” and his speculation that the ability to relate affirmative and negative sentences in this way is “perhaps an artifact of Western education and perhaps Aristotelian logic” (1974:9, quoted in Amritavalli 1977:9).

Cf. Ramadoss and Amritavalli (2007) for a discussion of Tamil clause structure.

Cf. Amritavalli (2004).

In the next section we see that Malayalam also has nominative subjects in gerunds, unexpected in a language where Tense licenses nominative case.

The main thrust of the review of A&J by Hany Babu and Madhavan (2002) is that tense-aspect homophony cannot suffice to motivate the reanalysis of tense as aspect in Malayalam. They however take no cognizance of the problems pointed out here and in A&J for the “Tensed” analysis of Malayalam.

We may speculate that in the history of Dravidian, agreement developed polarity when a neg illa developed, distinct from the neg -a of the negative conjugation. (The latter, I said, co-occurred with agreement in that conjugation; it was in complementary distribution with tense-aspect.) Then Malayalam exhibits a later stage in this development, wherein agreement is lost, and concomitantly, so is the polarity of the verbal tense-aspect morphology.

A&J remark (p. 197) that Jayaseelan had (in earlier work on Malayalam) indeed, for this reason, “misdiagnosed the category Tense in verb forms that are at best ambiguous between tensed and aspectual forms.”

References

Akmajian, Adrian. 1977. The complement structure of perception verbs in an autonomous syntax framework. In Formal syntax, eds. Peter Culicover, Thomas Wasow, and Adrian Akmajian, 427–460. New York: Academic Press.

Amritavalli, R. 1977. Negation in Kannada. Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby.

Amritavalli, R. 2000. Kannada clause structure. In Yearbook of South Asian languages, ed. Rajendra Singh, 11–30. New Delhi: Sage India.

Amritavalli, R. 2004. Some developments in the functional architecture of the Kannada clause. In Clause structure in South Asian languages, eds. Veneeta Dayal and Anoop Mahajan, Studies in natural language and linguistic theory, 13–38. Boston: Kluwer.

Amritavalli, R. 2010. Person checking in nominative and ergative languages. In Proceedings of GLOW in Asia VIII, 80–87. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press.

Amritavalli, R., and K. A. Jayaseelan. 2005. Finiteness and negation in Dravidian. In The Oxford handbook of comparative syntax, eds. Guglielmo Cinque and Richard S. Kayne, 178–220. New York: Oxford University Press.

Amritavalli, R., and K. A. Jayaseelan. 2007. Clause structure and early acquisition of split ergativity and negation. In GLOW in Asia VI: Parametric syntax and language acquisition. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Enç, Mürvet. 1987. Anchoring conditions for tense. Linguistic Inquiry 18(4): 633–657.

Hany Babu, M. T. 1996. The structure of Malayalam sentential negation. International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics 25(5): 1–15.

Hany Babu, M. T., and P. Madhavan 2002. The two lives of -unnu: A response to Amritavalli and Jayaseelan. CIEFL Occasional Papers in Linguistics 10.

Hariprasad, M. 1989. Negation in Telugu and English. M. litt thesis. CIEFL: Hyderabad.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 1984. Control in some sentential adjuncts of Malayalam. Berkeley Linguistics Society 10: 623–633.

Kayne, Richard S. 1991. Italian negative imperatives and clitic climbing. Ms., New York: CUNY.

Krifka, Manfred. 1995. The semantics and pragmatics of polarity items. Linguistic Analysis 25(3–4): 209–257.

Landau, Idan. 2004. The scale of finiteness and the calculus of control. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 22: 811–877.

Lin, Jo-wang. 2006. Time in a language without tense: The case of Chinese. Journal of Semantics 23: 1–53.

Lin, Jo-wang. 2010. A tenseless analysis of Mandarin Chinese revisited: A response to Sybesma 2007. Linguistic Inquiry 41(2): 305–329.

Menon, Mythili. 2011. Revisiting finiteness: The need for tense in Malayalam. Paper presented at FISAL: Tromsø.

Ramadoss, Deepti, and R. Amritavalli 2007. The Acquisition of functional categories in Tamil with special reference to negation. Nanzan Linguistics Special Issue 1: Papers from the Consortium Workshops on Linguistic Theory, 67–84. Graduate Program in Linguistic Science: Nanzan University.

Ritter, Elizabeth, and Martina Wiltschko. 2005. Anchoring events to utterances without tense. In Proceedings of the 24th West coast conference on formal linguistics, eds. John Alderete et al., 343–351. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. www.lingref.com, document #1240. Accessed 10 July 2013.

Ritter, Elizabeth, and Martina Wiltschko. 2009. Varieties of infl: Tense, location, and person. In Alternatives to cartography, ed. Jeroen van Craenenbroeck. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. http://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/000780/current.pdf. 31 August 2013.

Schiffman, H. F. 1974. Complex negation in Tamil: Semantic and syntactic aspects. Jaffna, Sri Lanka. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference of Tamil Studies.

Stowell, T. 1982. The tense of infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry 13: 561–570.

Stowell, T. 1995. The phrase structure of tense. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 277–291. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Zanuttini, Raffaella. 1991. Syntactic properties of sentential negation: A comparative study of Romance languages. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Amritavalli, R. Separating tense and finiteness: anchoring in Dravidian. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 32, 283–306 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9219-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-013-9219-3