Abstract

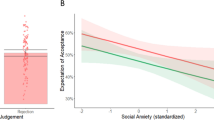

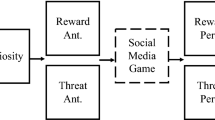

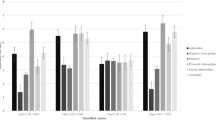

The present research aimed at answering the question why people differ in their way of attributing experienced social acceptance and rejection. Using a motivational approach, two scenario studies (Study 1, N = 280; Study 2, N = 232) and one study using actual social interactions (Study 3, N = 128) supported the hypothesis that dispositional social approach motives are associated with attributions following social acceptance (β = .16–.23, p < .001) but not social rejection (β = −.03 to −.06, p > .13), whereas dispositional social avoidance motives are associated with attributions following social rejection (β = .23–.29, p < .001) but not social acceptance (β = −.02 to −.08, p > .07). These studies demonstrate that social approach and avoidance motives are differentially predictive in social situations with positive compared to negative outcomes. Moreover, social motives play an important role in people’s attributions following their experiences of social acceptance or rejection. Taken together, the three studies suggest that people’s explanations of social acceptance and rejection differ as a function of what they generally want and fear in social interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The samples used for Studies 1 and 3 included younger and older adults because those studies were part of an overarching research project examining age differences between young and older adults with respect to social motives and diverse concomitants. The sample for Study 1 consisted of n = 171 younger (29 % men, age range 18–30 years, M = 24.30, SD = 3.42) and n = 109 older adults (58 % men, age range 60–84 years, M = 69.31, SD = 5.72).

The sample for Study 3 consisted of n = 63 younger (59 % men; age range 18–33 years, M = 23.65, SD = 3.56) and n = 65 older adults (52 % men; age range 61–85 years, M = 71.08, SD = 6.26).

There were no significant differences between attributions following the first and the second acceptance scenario (all ps > .34). Attributions following the rejection scenarios, however, differed significantly between the first and the second scenario [internal attribution first scenario: M = −0.21, SD = 1.46; internal attribution second scenario: M = 0.57, SD = 1.66, t(275) = −6.33, p < .001, d = −0.76; general attribution first scenario: M = −0.29, SD = 1.16; general attribution second scenario: M = 0.25, SD = 1.30, t(275) = −3.83, p < .001, d = −0.46].

We ran the same analyses separately for the attribution dimensions of stability and globality. The results concerning stability, globality, and generality did not differ systematically. We thus report the findings for the combined dimension of generality.

There were no significant differences between most attributions with regard to the order of acceptance and rejection interaction (1 = first position, 2 = second position) (all ps > .65). The attribution following the rejection interaction to internal causes however, significantly differed between the position of the acceptance and rejection interaction [first position of social rejection: M = −0.03, SD = 1.94; second position of social rejection: M = 0.70, SD = 1,74, t(125) = 2.06, p < .05, d = 0.37]. Therefore, we ran the analyses described in the results part of Study 3 controlling for the order of the acceptance and rejection condition. As these results did not differ systematically form the results without the control variable, we only report the findings without the control variables in the result section.

In contrast to Study 2, we assessed only feelings of acceptance after the manipulation and did not assess feelings of rejection. This decision was based on the high correlation of the two items in Study 2 (r = −.86, p < .001), indicating that they are the two poles of one scale. High values on the manipulation check indicate high feelings acceptance, whereas low values indicate high feelings of rejection.

In the second step of the regression analysis, we entered the interactions between social motives and each study. As only one of the sixteen interactions was statistically significant, these interactions will not be interpreted further.

References

Alden, L. (1986). Self-efficacy and causal attributions for social feedback. Journal of Research in Personality, 20, 460–473. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(86)90126-1.

Anderson, C. A., & Jennings, D. L. (1980). When experiences of failure promote expectations of success: The impact of attribution failure to ineffective strategies. Journal of Personality, 48, 393–407.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.117.3.497.

Brodt, S. E., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1981). Modifying shyness-related social behavior through symptom misattribution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 437–449. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.41.3.437.

Derryberry, D., & Reed, M. A. (1994). Temperament and attention: Orienting toward and away from positive and negative signals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 1128–1139. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.66.6.1128.

Feather, N. T. (1969). Attribution of responsibility and valence of success and failure in relation to initial confidence and task performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13, 129–144. doi:10.1037/h0028071.

Feather, N. T., & Simon, J. G. (1971). Causal attributions for success and failure in relation to expectations of success based upon selective or manipulative control. Journal of Personality, 39, 527–541. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1971.tb00060.x.

Gable, S. L. (2006). Approach and avoidance social motives and goals. Journal of Personality, 74, 175–222. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00373.x.

Gable, S. L., & Berkman, E. T. (2008). Making connections and avoiding loneliness: Approach and avoidance social motives and goals. In A. J. Elliot (Ed.), Handbook of approach and avoidance motivation (pp. 204–216). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Gable, S. L., & Impett, E. A. (2012). Approach and avoidance motives and close relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6, 95–108. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00405.x.

Gable, S. L., & Poore, J. (2008). Which thoughts count? Algorithms for evaluating satisfaction in relationships. Psychological Science, 19, 1030–1036. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02195.x.

Gable, S. L., Reis, H. T., & Elliot, A. J. (2003). Evidence for bivariate systems: An empirical test of appetition and aversion across domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 349–372. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00580-9.

Gardner, W. L., Pickett, C. L., & Brewer, M. B. (2000). Social exclusion and selective memory: How the need to belong influences memory for social events. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 486–496. doi:10.1177/0146167200266007.

Gomez, A., & Gomez, R. (2002). Personality traits of the behavioural approach and inhibition systems: Associations with processing of emotional stimuli. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 1299–1316. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00119-2.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York, NY: Wiley. doi:10.1037/10628-000.

Higgins, T., & Tykocinski, O. (1992). Self-discrepancies and biographical memory: Personality and cognition at the level of psychological situation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 527–535.

Kinderman, P., & Bentall, P. (1996). A new measure of causal locus: The internal, personal and situational attributions questionnaire. Personal Individual Differences, 20, 261–264. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(95)00186-7.

McClelland, D. C. (1985). Human motivation. Annual review of psychology. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

Mehrabian, A. (1970). The development and validation of measures of affiliative tendency and sensitivity to rejection. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30, 417–428. doi:10.1177/001316447003000226.

Mehrabian, A. (1994). Evidence bearing on the affiliative tendency (MAFF) and sensitivity to rejection (MSR) scales. Current Psychology, 13, 97–117. doi:10.1007/BF02686794.

Mehrabian, A., & Ksionzky, S. (1974). A theory of affiliation. Lexington, MA: Health.

Metalsky, G. I., Halberstadt, L. J., & Abramson, L. Y. (1987). Vulnerability to depressive mood reactions: Toward a more powerful test of the diathesis–stress and causal mediation components of the reformulated theory of depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 386–393. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.2.386.

Mezulis, A. H., Abramson, L. Y., Hyde, J. S., & Hankin, B. L. (2004). Is there a universal positivity bias in attributions? A meta-analytic review of individual, developmental, and cultural differences in the self-serving attributional bias. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 711–747. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.711.

Miller, D. T., & Ross, M. (1975). Self-serving biases in the attribution of causality: Fact or fiction? Psychological Bulletin, 82, 213–225. doi:10.1037/h0076486.

Morris, S. J. (2007). Attributional biases in subclinical depression: A schema-based account. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 47, 32–47. doi:10.1002/cpp.

Nikitin, J., Burgermeister, L. C., & Freund, A. M. (2012). The role of age and social motivation in developmental transitions in young and old adulthood. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 1–14. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00366.

Nikitin, J., & Freund, A. M. (2008). The role of social approach and avoidance motives for subjective well-being and the successful transition to adulthood. Applied Psychology, 57, 90–111. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00356.x.

Nikitin, J., & Freund, A. M. (2010). When wanting and fearing go together: The effect of co-occurring social approach and avoidance motivation on behavior, affect, and cognition. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 783–804. doi:10.1002/ejsp.650.

Nikitin, J., & Freund, A. M. (2011). Age and motivation predict gaze behavior for facial expressions. Psychology and Aging, 26, 695–700. doi:10.1037/a0023281.

Nikitin, J., Schoch, S., & Freund, A. M. (2014). The role of age and motivation for the experience of social acceptance and rejection. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1943–1950. doi:10.1037/a0036979.

Peterson, C., & Buchanan, G. M. (1995). Explanatory style: History and evolution of the field. In G. M. Buchanan & M. E. P. Seligman (Eds.), Explanatory style (pp. 1–20). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pickett, C. L., Gardner, W. L., & Knowles, M. (2004). Getting a cue: The need to belong and enhanced sensitivity to social cues. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1095–1107. doi:10.1177/0146167203262085.

Poppe, P., Stiensmeier-Pelster, J., & Pelster, A. (2005). Attributionsstilfragebogen für Erwachsene: ASF-E [Attributional pattern questionnaire for adults]. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Romero-Canyas, R., & Downey, G. (2012). What I see when I think it’s about me: People low in rejection-sensitivity downplay cues of rejection in self-relevant interpersonal situations. Emotion, 13, 104–117. doi:10.1037/a0029786.

Romero-Canyas, R., Downey, G., Berenson, K., Ayduk, O., & Kang, N. J. (2010). Rejection sensitivity and the rejection–hostility link in romantic relationships. Journal of Personality, 78, 119–148. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00611.x.

Sedikides, C., & Alicke, M. D. (2012). Self-enhancement and self-protection motives. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), Oxford handbook of motivation (pp. 303–322). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0017.

Sokolowski, K. (1986). Kognitionen und Emotionen in anschlussthematischen Situationen [Cognitions and emotions in affiliative situations]. Wuppertal: Bergische Universität.

Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. (1989). Attributional style and depressive mood reactions. Journal of Personality, 57, 581–599. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00564.x.

Strachman, A., & Gable, S. L. (2006). What you want (and do not want) affects what you see (and do not see): Avoidance social goals and social events. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 1446–1458. doi:10.1177/0146167206291007.

Weiner, B. (2000). Intrapersonal and interpersonal theories of motivation from an attributional perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 12, 1–14. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-1273-8_2.

Weiner, B., Frieze, I., Kukla, A., Reed, L., Rest, S., & Rosenbaum, R. M. (1987). Perceiving the causes of success and failure. In E. E. Jones, D. E. Kanouse, H. H. Kelley, R. E. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B. Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 95–120). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 100014_126868/1 (Project “Social Approach and Avoidance Motivation—The Role of Age”) from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PIs: Jana Nikitin and Alexandra M. Freund). We thank the Life-Management team for helpful discussions of the work reported in this article, and Mirjam Dönni, Christian Gross, and Mahmoud Hemmo for their help with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Acceptance condition (Study 2)

Imagine that you are invited to participate in a study in which you are to become acquainted with someone of same age and gender within 5 min. As your interaction partner does not initiate the conversation, you start by introducing yourself. After exchanging a few words, the conversation gets more and more lively. Your interaction partner maintains eye contact with you, listens attentively, and seems to show interest in you. It is easy to find common interests. The conversation is very spirited and your interaction partner seems to find the topics discussed interesting. At the end, your interaction partner says: “Wow, that went by fast!” You feel accepted.

Rejection condition (Study 2)

Imagine that you are invited to participate in a study in which you are to become acquainted with someone of same age and gender within 5 min. As your interaction partner does not initiate the conversation, you start by introducing yourself. After exchanging a few words, the conversation stops. Your interaction partner rarely looks at you, does not listen attentively to you, and seems to lack interest in you. You try to come up with new topics in order to find common ground, but the conversation continues to move slowly. Your interaction partner does not seem to find the topics discussed interesting. At the end, your interaction partner says: “Wow, that took forever!” You feel rejected.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schoch, S., Nikitin, J. & Freund, A.M. Why do(n’t) you like me? The role of social approach and avoidance motives in attributions following social acceptance and rejection. Motiv Emot 39, 680–692 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9482-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9482-1