Abstract

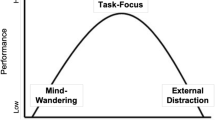

According to motivational intensity theory, energy investment in goal pursuit is determined by the motivation to avoid wasting energy. Two experiments tested this hypothesis by manipulating the difficulty of an isometric hand grip task across four levels in a between-persons (Study 1) and a within-persons (Study 2) design. Supporting motivational intensity theory’s prediction, the results showed that invested energy—indicated by exerted grip force—was a function of task difficulty: The higher the difficulty, the higher the energy investment. However, the data also indicated that participants invested considerably more energy than required, questioning the primacy of energy conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These predictions only hold if task difficulty is fixed and known. A comprehensive discussion of all predictions of motivational intensity theory can be found in Richter (2013).

Participants' maximum force was assessed to assure that the requested force standards did not exceed participants' maximum force (i.e., to assure that task success was possible). It was also assessed to control for individual differences in maximum force in the statistical analysis of exerted force.

Bayesian t tests were conducted using a unit-information prior with known variance, the same prior that underlies the BIC calculation.

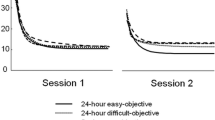

Classical null hypothesis significance testing resulted in F(1, 68) = 25.16, p < .001, MSE = 1,126.29 for the linear effect of task difficulty on peak force and F(1, 68) = 10.56, p = .002, MSE = 642,391.26 for the linear effect of task difficulty on FTI.

For both experiments, all analyses were also conducted controlling for participants' maximum force. Given that this did virtually not change the results, only the uncorrected analyses are reported.

The mean of the individual coefficients of variation was 25.41. The ICC [1, 1] was .64.

Classical null hypothesis significance testing resulted in F(1, 48) = 50.03, p < .001, MSE = 388.92 for the linear effect of task difficulty on peak force and F(1, 48) = 78.99, p < .001, MSE = 96,549.39 for the linear effect of task difficulty on FTI.

References

Backs, R. W., & Seljos, K. A. (1994). Metabolic and cardiorespiratory measures of mental effort: The effects of level of difficulty in a working memory task. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 16, 57–68.

Boska, M. (1994). ATP production rates as a function of force level in the human gastrocnemius/soleus using 31P MRS. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 32, 1–10. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910320102.

Brehm, J. W., & Self, E. A. (1989). The intensity of motivation. Annual Review of Psychology, 40, 109–131. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.000545.

Brener, J. (1987). Behavioural energetics: Some effects of uncertainty on the mobilization and distribution of energy. Psychophysiology, 24, 499–512.

Brener, J., & Mitchell, S. (1989). Changes in energy expenditure and work during response acquisition in rats. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Process, 15, 166–175.

Carroll, D., Turner, J. R., & Prasad, R. (1986). The effects of level of difficulty of mental arithmetic challenge on heart rate and oxygen consumption. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 4, 167–173.

Dixon, P. (2003). The p-value fallacy and how to avoid it. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 57, 189–202.

Eubanks, L., Wright, R. A., & Williams, B. J. (2002). Reward influences on the heart: Cardiovascular response as a function of incentive value at five levels of task demand. Motivation and Emotion, 26, 139–152. doi:10.1023/A:1019863318803.

Fagraeus, L., & Linnarsson, D. (1976). Autonomic origin of heart rate fluctuations at the onset of muscular exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 40, 679–682.

Fairclough, S. H., & Houston, K. (2004). A metabolic measure of mental effort. Biological Psychology, 66, 177–190. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2003.10.001.

Filion, R. D. L., Fowler, S. C., & Notterman, J. N. (1970). Effort expenditure during proportionally reinforced responding. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 22, 398–405. doi:10.1080/14640747008401913.

Gendolla, G. H. E., Richter, M., & Silvia, P. J. (2008). Self-focus and task difficulty effects on effort-related cardiovascular reactivity. Psychophysiology, 45, 653–662. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00655.x.

Gendolla, G. H. E., Wright, R. A., & Richter, M. (2012). Effort intensity: Some insights from the cardiovascular system. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), The oxford handbook on motivation (pp. 420–438). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Jeneson, J. A. L., Westerhoff, H. V., Brown, T. R., Van Echteld, C. J. A., & Berger, R. (1995). Quasi-linear relationship between Gibbs free energy of ATP hydrolysis and power output in human forearm muscle. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology, 37, C1474–C1484.

Johansson, T. (2011). Hail the impossible: p-Values, evidence, and likelihhod. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 52, 113–125. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9450.2010.00852.x.

Lay, B. S., Sparrow, W. A., Hughes, K. M., & O’Dwyer, N. J. (2002). Practice effects on coordination and control, metabolic energy expenditure, and muscle activation. Human Movement Science, 21, 807–830. doi:10.1016/S0167-9457(02)00166-5.

Masson, M. E. J. (2011). A tutorial on a practical Bayesian alternative to null-hypothesis. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 679–690. doi:10.3758/s13428-010-0049-5.

Maughan, R. J., & Gleeson, M. (2010). The biochemical basis of sports performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McClelland, D. C., Atkinson, J. W., Clark, R. A., & Lowell, E. L. (1953). The achievement motive. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Obrist, P. A. (1981). Cardiovascular psychophysiology: A perspective. New York, NY: Plenum.

Potma, E. J., Stienen, G. J. M., Barends, J. P. F., & Elzinga, G. (1994). Myofibrillar ATPase activity and mechanical performance of skinned fibres from rabbit psoas muscle. Journal of Physiology, 474, 303–317.

Prompers, J. J., Jeneson, J. A. L., Drost, M. R., Oomens, C. C. W., Strijkers, G. J., & Nicolay, K. (2006). Dynamic MRS and MRI of skeletal muscle function and biomechanics. NMR in Biomedicine, 19, 927–953. doi:10.1002/nbm.

Proske, U., & Gandevia, S. C. (2012). The proprioceptive senses: Their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiological Reviews, 92, 1651–1697. doi:10.1152/physrev.00048.2011.

Raftery, A. E. (1995). Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology, 25, 111–163. doi:10.2307/271063.

Richter, M. (2013). A closer look into the multi-layer structure of motivational intensity theory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7, 1–12. doi:10.1111/spc3.12007.

Richter, M., Friedrich, A., & Gendolla, G. H. E. (2008). Task difficulty effects on cardiac activity. Psychophysiology, 45, 869–875. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00688.x.

Richter, M., & Gendolla, G. H. E. (2009). The heart contracts to reward: Monetary incentives and preejection period. Psychophysiology, 46, 451–457. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00795.x451-457.

Rouder, J. N., Morey, R. D., Speckman, P. L., & Province, J. M. (2012). Default Bayes factors for ANOVA designs. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 56, 356–374. doi:10.1016/j.jmp.2012.08.001.

Rouder, J. N., Speckman, P. L., Sun, D., Morey, R. D., & Iverson, G. (2009). Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 16, 225–237. doi:10.3758/PBR.16.2.225.

Russ, D. W., Elliott, M. A., Vandenborne, K., Walter, G. A., & Binder-Macleod, S. A. (2002). Metabolic costs of isometric force generation and maintenance of human skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology—Endocrinology and Metabolism, 282, E448–E457. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00285.2001.

Scholey, A. B., Harper, S., & Kennedy, D. O. (2001). Cognitive demand and blood glucose. Physiology & Behavior, 73, 585–592.

Sherwood, A., Allen, M. T., Obrist, P. A., & Langer, A. W. (1986). Evaluation of beta-adrenergic influences on cardiovascular and metabolic adjustments to physical and psychological stress. Psychophysiology, 23, 89–104.

Sherwood, A., Brener, J., & Moncur, D. (1983). Information and states of motor readiness: Their effects on the covariation of heart rate and energy expenditure. Psychophysiology, 20, 513–529.

Sims, J., & Carroll, D. (1990). Cardiovascular and metabolic activity at rest and during psychological and physical challenge in normotensives and subjects with mildly elevated blood pressure. Psychophysiology, 27, 149–156.

Sparrow, W. A., & Newell, K. M. (1994). Energy expenditure and motor performance relationships in humans learning a motor task. Psychophysiology, 31, 338–346. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1994.tb02442.x.

Stienen, G. J., Kiers, J. L., Bottinelli, R., & Reggiani, C. (1996). Myofibrillar ATPase activity in skinned human skeletal muscle fibres: Fibre type and temperature dependence. Journal of Physiology, 493, 299–307.

Szentesi, P., Zaremba, R., van Mechelen, W., & Stienen, G. J. M. (2001). ATP utilization for calcium uptake and force production in different types of human skeletal muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology, 531, 393–403.

Turner, J. R., & Carroll, D. (1985). Heart rate and oxygen consumption during mental arithmetic, a video game, and graded exercise: Further evidence of metabolically-exaggerated cardiac adjustments? Psychophysiology, 22, 261–267.

Victor, R. G., Seals, D. R., Mark, A. L., & Kempf, J. (1987). Differential control of heart rate and sympathetic nerve activity during dynamic exercise. Insight from intraneural recordings in humans. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 79, 508–516. doi:10.1172/JCI112841.

Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2007). A practical solution to the pervasive problems of p values. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14, 779–804.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68–81. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1015.

Wright, R. A. (1996). Brehm’s theory of motivation as a model of effort and cardiovascular response. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 424–453). New York, NY: Guilford.

Wright, R. A. (2008). Refining the prediction of effort: Brehm’s distinction between potential motivation and motivation intensity. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 682–701. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00093.x.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a research Grant (10014_134586) from the Swiss National Science Foundation. I am grateful to Kerstin Brinkmann and Guido H. E. Gendolla for comments on an early version of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richter, M. Goal pursuit and energy conservation: energy investment increases with task demand but does not equal it. Motiv Emot 39, 25–33 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9429-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9429-y