Abstract

Although many studies report positive effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on customer attitudes, recent literature shows that the effectiveness of CSR initiatives critically varies among consumers, brands, and companies. Using 1375 customer responses about 93 brands in 18 industries, we examine how perceived CSR relates to customer attitudes and actual retention 2 years later, and specifically how this relationship may be contingent on brand characteristics. Our results indicate that perceived CSR can indeed compensate for the absence of a strong brand or smaller advertising budgets, but not for lack of innovativeness. Companies that simultaneously do good and innovate are rewarded with more positive customer attitudes and higher levels of customer retention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Recent economic and financial crises have sparked vigorous debates about the societal role of firms, with Porter and Kramer (2011) specifically declaring the need for a stronger focus on social value creation to generate trust in firms. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives are therefore significant elements of the corporate strategy of many multinational corporations, whose CEOs, such as Unilever’s Paul Polman, assert that businesses can be a positive force for good in the world and that this perspective is in the interests of all firms’ stakeholders (Stern 2010).

In management and marketing literature, extensive attention to CSR has yielded the following definition: CSR is a firm’s commitment to ensuring societal and stakeholder well-being through discretionary business practices and contributions of corporate resources (Du et al. 2011). As a broad concept, CSR can include business practices as diverse as cash donations to charity, equitable treatment of workers, and an environmentally friendly production policy. Although CSR chiefly benefits society, many firms additionally strive to “do better by doing good” and gain competitive advantages through CSR (Prout 2006; Luo and Du 2015).

While an extensive literature stream examining the effects of CSR on financial performance has predominantly found small positive returns to CSR efforts (for an overview over these studies, see Margolis et al. 2007; Orlitzky et al. 2003), research on consumers’ responses to CSR efforts is more limited (Ailawadi et al. 2014). A downside of current literature investigating consumers’ response to CSR initiatives is its focus on consumers’ attitudes and intentions rather than behavioral measures. A notable exception finds predominantly positive effects of perceived CSR on self-reported consumer share-of-wallet, except for activities related to environmental friendliness (Ailawadi et al. 2014). To the best of our knowledge, no studies so far have investigated the impact of CSR efforts on actual customer retention, although customer retention is a very important outcome variable for firms (e.g., Katsikeas et al. 2016). Furthermore, while the literature cautions that the effectiveness of CSR initiatives may differ between companies and brands (e.g., Du et al. 2011; Torelli et al. 2012), attention is lacking with respect to when doing good leads to increased loyalty. This neglect leads to the two central research questions that guide this study:

-

(1)

What is CSR’s effect on customer attitudes and retention?

-

(2)

Does CSR’s effect on customer attitudes and retention depend on brand characteristics?

In line with previous literature (e.g., Ailawadi et al. 2014; Lichtenstein et al. 2004), we expect perceived CSR to affect customer attitudes, with the effect on retention being largely mediated by customer attitudes. Building on this assumption, we mainly elaborate on the second research question in our discussion of theory and conceptual development.

We address our research questions through a longitudinal study of 1375 responses from customers of 93 firms in 18 industries for which we observe perceived CSR, customer attitudes, and customer retention 2 years after the initial study. We contribute to the existing literature on CSR in three ways. First, we investigate the moderating role of brand-level variables on the CSR–customer loyalty relationship. Second, we study a large number of brands in multiple industries, allowing us to reach more generalizable conclusions. So far, studies of consumers’ response to CSR have focused on either a single industry or market (e.g., Ailawadi et al. 2014; Du et al. 2011) or a single brand (e.g., Sen and Bhattacharya 2001). Finally, our study is the first to investigate customer retention as an outcome variable of perceived CSR.

2 Theoretical background

Although many studies find positive effects of CSR on customer responses such as customer commitment and general company evaluations (Lacey and Kennett-Hensel 2010; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001), recent literature also shows that CSR initiatives can have a dark side. For instance, CSR initiatives may negatively affect evaluations of luxury brands (Torelli et al. 2012) or of products in certain product categories (e.g., Luchs et al. 2010). Literature also cautions that the effectiveness of CSR critically depends on company characteristics and strategy. For instance, CSR efforts may pay off more solidly for a market challenger than for a market leader (Du et al. 2011). These countervailing effects might explain why many studies find no significant effect of CSR on firm performance (Kang et al. 2016). As a result, company or brand characteristics become critical differentiators between firms that can successfully engage in CSR and those that can at best expect no effect of their CSR efforts.

One line of reasoning posits that engaging in CSR as a strategy better suits successful companies. Consumers may have a lay theory that company resources are zero-sum, implying that resources that are invested in improving a company’s CSR record are diverted from strengthening a company’s market position and improving a company’s products and/or services (Newman et al. 2014). Therefore, consumers may perceive that less successful companies’ engagement in CSR comes at the expense of developing stronger corporate abilities (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006), and reason that only successful companies possess sufficient slack resources to invest in CSR (Kang et al. 2016). This line of reasoning is supported by literature cautioning that CSR efforts of less innovative companies may be interpreted as focusing on the wrong priorities (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006; Newman et al. 2014). Engaging in CSR may then reinforce company success and improve customer attitude and retention, particularly toward already successful companies.

A second line of reasoning emphasizes that successful companies have less to gain by engaging in CSR. Customers of successful companies already have positive attitudes and high retention rates, leaving less potential for CSR to further increase attitudes and create loyalty (Du et al. 2011; Henderson and Arora 2010). This argument suggests that engaging in CSR is a more worthwhile strategy for less solid, well known, and successful companies to build positive attitudes and loyalty. Such a perspective is in line with findings that the effect of CSR on performance is smaller for market leaders (Du et al. 2011), and that the additional effect from a cause-related marketing campaign is limited for companies that are already seen as ethical (Strahilevitz 2003). CSR can therefore compensate for companies’ weaknesses and is in particular effective for increasing attitudes and loyalty toward less successful companies.

3 Conceptual development

Prior research thus seems to suggest that the effect of CSR on performance depends on firms’ success in the market. We investigate how various indicators of brand success moderate the relationship between CSR and brand attitudes and retention.Footnote 1 As consumers may assess brand success according to various criteria, we consider four indicators of brand success from a marketing and consumer perspective. These indicators range from more attitudinal measures evaluating whether a customer likes a brand and is aware of a brand to more objective measures detailing whether a brand has a dominant market position or is a market leader in terms of potential for innovation.

Brand strength is customers’ subjective, attitudinal assessment of the brand (Henderson and Arora 2010). Previous literature suggests that customers identify with strong brands (Lam et al. 2010), implying positive attitudes and loyalty. For strong brands, therefore, a ceiling effect may limit the additional value of CSR activities.

Advertising reflects customers’ awareness of a brand. Higher levels of advertising increase customers’ brand awareness and may stimulate customers to become further informed about the brand, including its CSR policies. Advertising specifically related to CSR may improve consumer awareness of a brand’s CSR, thus enhancing the impact of CSR, although advertising featuring CSR may also backfire (Servaes and Tamayo 2013; Yoon et al. 2006).

Market leadership is a more objective measure of a brand’s market success, as market followers may have on the one hand more to gain from CSR (Du et al. 2011), but on the other hand may have more pressing priorities than CSR. Finally, we include innovativeness of the brand as an indicator of brand success. As pioneers in their field, innovative brands may have less to gain from engaging in CSR. However, they are also less likely to be blamed for focusing on the wrong priorities.

4 Research design

4.1 Data

We obtained the data for our study from two customer surveys and an expert survey. Furthermore, we collected secondary advertising data from AC Nielsen and determined market leadership on the basis of revenue data published in the firms’ annual statements.

From September to November 2010, a large Dutch market research agency distributed web-based surveys to a panel of Dutch customers as part of a yearly large-scale study of customer performance. Panel members were randomly selected and received around €2 for participation. For each industry, respondents answered questions about various firms they patronized. The questions were asked at the subsidiary—that is, brand—level, implying that if companies held multiple brands, the customer was questioned about only one of them. For example, one of the largest providers in the insurance market has multiple brands and uses a multi-brand strategy, but does not actively communicate those brands as being owned by one firm. The total sample of our first survey featured 8924 responses from 6649 participants, in reference to 95 brands in 18 industries, such as telecommunications, travel agencies, banks, department stores, and supermarkets. This response volume implies an average number of 1.34 brands evaluated per respondent, as respondents could evaluate a maximum of three brands in total.

For our second survey, we contacted customers from our first survey at the end of 2012 to inquire whether they were still a customer of the brand they answered questions about in the first survey. This approach yielded a sample of 1375 customer responses relating to 93 brands (two companies had ceased to exist) in 18 industries. Of the responses, 52.1% came from male respondents. Age was balanced across five preset age categories, indicating a good representation of customers of all ages. With respect to income, most respondents earned €30,000–€60,000 annually.

The expert survey was conducted in April 2011. After a pretest, we sent e-mail questionnaires to 1440 marketing and marketing intelligence employees selected from a list maintained by a scientific research center. Prior to filling out the questionnaires, managers chose industries for which they were most knowledgeable and comfortable about answering questions. The 244 questionnaires received represented a response rate of 16.9%. After eliminating incomplete questionnaires, we obtained a total of 158 usable surveys, which offered a minimum of 15 and a maximum of 59 responses per industry.

4.2 Measures

We used existing scales to measure most of the variables (Table 1). Our measure of perceived CSR, which we obtained for 34 of our 93 companies, is significantly correlated with the ASSET4 ratings from Datastream (r = .482, p < .01 for ASSET4 environmental, r = .501, p < .01 for ASSET4 social, and r = .397, p < .05 for the weighted overall ASSET4 rating).

We assessed innovativeness by asking the experts how often a brand introduces innovative products, services, and ideas (Verhoef and Leeflang 2009). Data about brands’ advertising expenditures came from ACNielsen. To ensure comparability in the level of brand advertising across industries, we calculated advertising ratios by dividing the advertising expenditures per brand by the total amount of advertising expenditures per industry.

We measured firms’ market position by their revenue ranking in the corresponding industries. We collected revenue information from firms’ annual reports (Ou et al., 2017). For firms that were not listed on the stock market and/or had multiple brands, we used industry reports to collect information about a brand’s market share. We then distinguished the market leader as the brand with the highest market share in an industry.

4.3 Reliability

Cronbach’s α values exceeded the critical threshold of .7 (Peterson 1994), and a rotated factor analysis of the items confirmed that separate factors represented each of the customer-level constructs. Therefore, the items were summed. Because we obtained substantial information from the first customer survey, we performed a common method bias test. In addition to the measures in Table 1, we included a measure of consumer confidence in the survey, which we used as a marker variable in a common method bias test (Lindell and Whitney 2001). This test showed no problematic results. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics of the variables, appendix A, the correlations. We standardized and mean-centered our variables prior to any further analysis.

4.4 Model development

We specify a multilevel regression model to test our hypotheses because the data set comprises three levels, such that customers are nested in brands and brands are nested in industries (Snijders and Bosker 2012). We use a random intercept model, specified mathematically as follows:

with β 0jk = β 00k + u 0jk

with γ 0jk = γ 00k + ϑ 0jk

where

- attitude ijk :

-

Attitude of customer i toward brand j in industry k;

- CSR ijk :

-

Perceived CSR by customer i of brand j in industry k;

- brandstrength ijk :

-

Strength of brand j in industry k according to customer i;

- advertising jk :

-

Advertising ratio of brand j in industry k;

- leader jk :

-

Dummy variable (1 = brand j in industry k is market leader);

- innovative jk :

-

Innovativeness of brand j in industry k;

- Gender ijk :

-

Gender of customer i (1 = male);

- Age ijk :

-

Age of customer i;

- Income ijk :

-

Income of customer i;

- retention ijk :

-

Dummy variable (1 = customer i of brand j in industry k stayed loyal).

We estimate the attitude and retention models separately (Ailawadi et al. 2014). Likelihood ratio tests reveal (p < .01) that our model outperforms the intercept-only model and that our multilevel model outperforms an OLS/logistic regression model.

5 Impact of perceived CSR on customer attitudes and retention

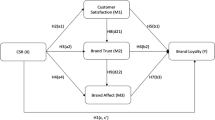

We present our results in Table 2 and give a visual overview of our framework and results in Fig. 1. As expected, perceived CSR relates positively and significantly to customer attitude (b = .333, p < .01). Brand strength positively affects attitude (b = .482, p < .01), while innovativeness, advertising, and market leadership do not affect customer attitudes.

As expected, customer attitude has a strong positive impact on actual retention (b = .434, p < .01), while perceived CSR does not (b = −.098, p > .1) (Table 3). Mediation tests for dichotomous outcomes (Kenny 2013) using a bootstrapping approach (5000 re-samples) with retention as the dependent variable, CSR as the independent variable, and attitude as the mediator show a positive mean indirect effect with the 95% confidence intervals not including zero (a × b = .113, 95% CI = .046 to .180). These results suggest that customer attitude mediates the effect of perceived CSR on customer retention (Ailawadi et al. 2014).

With regard to the moderating effects, we find significant interactions of CSR with brand strength (b = −.060; p < .01), advertising (b = −.049, p < .05), and innovativeness (b = .045. p < .05). The positive interaction effect between innovativeness and CSR contrasts with our theoretical expectations. No support is provided for a moderating effect of market leadership (b = −.05; p > .10). We also assessed interactions between CSR and the moderators in the retention model. Only the effect of perceived CSR on retention appears to be stronger for more innovative companies (b = .137, p < .1), although only at the 10% significance level.

We performed several additional analyses to confirm the robustness of the results in Table 2. First, we checked for industry-specific differences in our specified relationships via random coefficients models. The results remained similar. Only the relationship between perceived CSR and customer attitude shows industry-specific differences (p(LR-test) <.05); all other relationships do not (p(LR-test) >.1). We therefore prefer the more parsimonious random intercept model. Second, we added interactions between perceived CSR and the demographic control variables to investigate whether the impact of perceived CSR on attitudes and retention differed between demographic profiles and found that the attitude of older people was influenced more by perceived CSR (b = .056, p < .01) while all other results remained stable. Third, the highest VIF score is 2.04, indicating that multicollinearity was unlikely to be a problem (Hair et al. 2009).

6 Discussion

The main objective of this research was to investigate the effect of perceived CSR on customer attitude, in particular to what extent it is shaped by indicators of brand success, and its effect on retention. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to relate perceived CSR to customer attitudes and actual retention for such a large number of brands in multiple industries. As an important initial finding, we can reaffirm that CSR has a positive effect on customer attitude, which in turn predicts actual customer retention 2 years later. However, 2 years after our initial survey, we find no strong link between actual retention and perceived CSR and its interactions with brand characteristics, with the notable exception of innovative companies. This result relates to observations in the literature that CSR matters less for actual purchase behavior than quality considerations and price (Bhattacharya and Sen 2004).

As a second important contribution, we advance recent empirical findings that caution that CSR might not be a good strategy for all brands (Du et al. 2011; Luo and Bhattacharya 2009). We find that brands that do well on more attitudinal measures of brand success may benefit less from doing good. This result may be due to ceiling effects, implying that attitudes toward brands that are already positively evaluated and have high levels of brand awareness are less likely to improve through CSR. In particular, we find that perceived CSR makes a more notable difference for attitudes toward weaker brands. We therefore generalize to a between-firm level the assertion from prior work that a social cause attached to a product or service benefits an unknown brand more than a well-known brand (Arora and Henderson 2007).

Furthermore, we find that perceived CSR matters more for the attitude toward brands with lower advertising ratios. Intense advertising creates awareness of and familiarity with a brand, implying that brands that advertise less have more to gain from engaging in CSR. Interestingly, these results contrast with the earlier finding that good corporate social performance decreases firm-idiosyncratic risk to a greater extent for brands with higher advertising (Luo and Bhattacharya 2009). We can only speculate about the reasons for this divergence, the most obvious one being that Luo and Bhattacharya (2009) investigate firm-level effects using secondary data sources whereas we look at customer-level outcomes (e.g., Katsikeas et al. 2016).

Interestingly, we find the opposite result when we turn to measures that more strongly reflect a brand’s position in the market, in particular a brand’s propensity to introduce innovative products and/or services. Perceived CSR does not compensate for lower innovativeness. Rather, innovativeness and CSR reinforce each other. Notably, innovativeness is the only moderator we examine that affects the impact of perceived CSR on both attitude and retention. Innovative companies can clearly benefit from engaging in CSR. This result is in line with literature cautioning that CSR efforts of less innovative companies may focus on the wrong priorities (Luo and Bhattacharya 2006; Newman et al. 2014).

Figure 2 depicts the joint effect of brand strength and innovativeness for the effectiveness of CSR. Figure 2a, reveals that weak brands enjoy the strongest increase in customer attitudes when they engage in CSR, whereas innovativeness makes less of a difference. However, regarding customer retention, brands that are not innovative do not benefit from engaging in CSR, regardless of their brand strength (Fig. 2b,).

Moderating effect of perceived CSR on attitude and retention (To obtain Fig. 2a, we varied the levels of brand strength, innovativeness, and perceived CSR (“high” one SD above the mean, “low” one SD below the mean), leaving the other variables at their mean)

We find no evidence that perceived CSR matters more for a market follower than for a market leader, a result that contrasts with findings in a two-brand setting (Du et al. 2011). An explanation for a significant negative interaction effect of brand strength and advertising, but not market leadership, with perceived CSR on attitude may be that the first two measures are more closely connected to how the firm is reflected in customers’ minds, whereas market leadership concerns a brand’s actual position in the market, which does not necessarily mean that people like the brand (Katsikeas et al. 2016). For example, Wal-Mart might have a high market share, but customers might feel less connection with that brand.

7 Limitations and further research

We note several limitations associated with this research. First, we gathered data only from the Netherlands, which makes generalizing the findings to other countries or cultural settings difficult. Second, the industries included are primarily service-oriented, such as telecommunications, banks, and insurance firms, or only partly service-oriented, such as department stores and supermarkets. Third, we used customer attitude and retention as our focal variables, but performance metrics such as total sales and profits might also be valuable to study. Fourth, we did not study actual CSR efforts and their relationships with CSR perceptions. Finally, we note that this study mainly presents initial findings on the moderating role of brand success indicators on the CSR brand attitude and retention relationship.

Further research could build upon our findings and develop and test theory. Specifically, research could focus on uncovering the underlying mechanisms for the occurrence of these moderating effects. For brand strength, we discussed the role of ceiling effects, whereas for innovative brands, the perceived focus on the right priorities may be an explanation. While empirical evidence is thus present for three of the studied brand success indicators, research should theorize and test why these moderating effects occur.

Notes

The robust stream of literature examining the effects of CSR on financial performance (e.g., Margolis et al. 2007) usually takes the company as unit of analysis. However, when examining the impact of CSR on customer attitudes and retention, one has to take into account that many companies adopt a multi-brand strategy (Keller 2014) and may not actively communicate that these brands belong to the same company. Given that customers form attitudes and are loyal to these brands, and not their parent companies, we adopt the customer’s perspective and take the brand as unit of analysis.

References

Aaker, D. A. (1996). Measuring brand equity across products and markets. California Management Review, 38, 102–120.

Ailawadi, K. L., Neslin, S. A., Luan, Y. J., & Taylor, G. A. (2014). Does retailer CSR enhance behavioral loyalty? A case for benefit segmentation. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 31, 156–167.

Arora, N., & Henderson, T. (2007). Embedded premium promotion: why it works and how to make it more effective. Marketing Science, 26, 514–531.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2004). Doing better at doing good: when, why and how customers respond to corporate social initiatives. California Management Review, 47, 9–24.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2007). Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 24(3), 224–241.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage: overcoming the trust barrier. Management Science, 57, 1528–1545.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Henderson, T., & Arora, N. (2010). Promoting brands across categories with a social cause: implementing effective embedded premium programs. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 41–60.

Kang, C., Germann, F., & Grewal, R. (2016). Washing your sins? Corporate social responsibility, corporate social irresponsibility and firm performance. Journal of Marketing, 80(2), 59–79.

Katsikeas, C. S., Morgan, N. A., Leonidou, L. C., & Hult, T. M. (2016). Assessing performance outcomes in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 80(2), 1–20.

Keller, K. L. (2014). Designing and implementing brand architecture strategies. Journal of Brand Management, 21(9), 702–715.

Kenny, D. A. (2013). Mediation with Dichotomous Outcomes. Retrieved January 19th 2015 from website: http://davidakenny.net/doc/dichmed.pdf.

Lacey, R., & Kennett-Hensel, P. A. (2010). Longitudinal effects of corporate social responsibility on customer relationships. Journal of Business Ethics, 97, 581–597.

Lam, S., Ahearne, M., Hu, Y., & Schillewaert, N. (2010). Resistance to brand switching when a radically new brand is introduced: a social identity theory perspective. Journal of Marketing, 74, 128–146.

Lichtenstein, D. R., Drumwright, M. E., & Braing, B. M. (2004). The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. Journal of Marketing, 68, 16–32.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 114–121.

Luchs, M. G., Naylor, R. W., Irwin, J. R., & Raghunathan, R. (2010). The sustainability liability: potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference. Journal of Marketing, 74, 18–31.

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70, 1–18.

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2009). The debate over doing good: corporate social performance, strategic marketing levers, and firm-idiosyncratic risk. Journal of Marketing, 73, 198–213.

Luo, X., & Du, S. (2015). Exploring the relationship between corporate social responsibility and firm innovation. Marketing Letters, 26, 703–714.

Margolis, J. D., Elfenbein, H. A., & Walsh, J. P. (2007). Does it pay to be good? A meta-analysis and redirection of research on the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48, 268–305.

Newman, G. E., Gorlin, M., & Dhar, R. (2014). When going green backfires: how firm intentions shape the evaluation of socially beneficial product enhancements. Journal of Consumer Research, 41, 823–839.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: a meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24, 403–441.

Ou, Y. C., Verhoef, P. C., & Wiesel, T. (2017). The effects of customer equity drivers on loyalty across services industries and firms. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, forthcoming.

Peterson, R. A. (1994). A meta-analysis of Cronbach's coefficient alpha. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 381–391.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value: how to reinvent capitalism—and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review, 89, 62–77.

Prout, J. (2006). Corporate responsibility in the global economy: a business case. Society and Business Review, 1, 184–191.

Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Customer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38, 225–244.

Servaes, H., & Tamayo, A. (2013). The impact of corporate social responsibility on firm value: the role of customer awareness. Management Science, 59, 1045–1061.

Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. (2012). Multilevel analysis (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Stern, S. (2010). The Outsider in a Hurry to Shake Up His Company. Financial Times, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/942c64a6-404a-11df-8d2300144feabdc0.html#axzz3n2awspSB.

Strahilevitz, M. (2003). The effects of prior impressions of a firm’s ethics on the success of a cause-related marketing campaign: do the good look better while the bad look worse? Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 11(1), 77–92.

Torelli, C. J., Basu-Monga, S., & Kaikati, A. (2012). Doing poorly by doing good: corporate social responsibility and brand concepts. Journal of Consumer Research, 38, 948–963.

Verhoef, P. C., & Leeflang, P. S. H. (2009). Understanding the marketing department’s influence within the firm. Journal of Marketing, 73, 14–37.

Yoon, Y., Gürhan-Canli, Z., & Schwarz, N. (2006). The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 377–390.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van Doorn, J., Onrust, M., Verhoef, P.C. et al. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer attitudes and retention—the moderating role of brand success indicators. Mark Lett 28, 607–619 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-017-9433-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-017-9433-6