Abstract

In recent past the concept of the ‘network’ or ‘network organization’ has emerged as one of the most prominent concepts for thinking, understanding and conceptualizing the coordination of ‘productive activities’. In the literature on network organizations, ‘trust’ is commonly understood to be the main coordinating mechanism of this organizational form. Highlighting the problematics involved in this prime focus on trust, this study combines practice-based theory (Schatzki in Social practices: a Wittgensteinian approach to human activity and the social, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2008) and a Foucauldian understanding of governing to contribute to a more differentiated understanding of the coordination of everyday activities in network organizations. By focusing on how the ‘network organization’ and its subjects are ‘produced’ in power-infused practices, this study provides insights into the complexity of mechanisms involved in such organizations. Empirically this is illustrated at the example of a consulting company which describes itself—internally and externally—as ‘network organization’. Based on an ethnographic participant observation and in-depth semi-structured interviews, the analysis of the case questions the centrality of trust as coordinating mechanism and provides deep insights into the constitution of this specific ‘network organization’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Castells (1996) argues that ‘networks are the fundamental stuff of which new organizations are and will be made’ (p. 168). One may or may not agree with the tremendous importance Castells ascribes to networks. However, networks do play a major role in contemporary civil society and the economic system (see also e.g. Powell 2001; Tilly 2001; Kornberger and Gudergan 2006). The body of research on social networks has grown extensively in the last three decades (Kilduff and Brass 2010; Carpenter et al. 2012) and ‘network’ as a concept is used in many different ways in diverse research contexts and disciplines. Within the social sciences, ‘networks’ have for example been approached as a context defining and shaping strategic alliances (e.g. Gulati 1998) or economic action more generally (e.g. Granovetter 1985; Lomi 1997). At the same time, networks have been approached as personal resources that can be drawn on to see and realize certain opportunities (e.g. Burt 1997), as potential sources of power (e.g. Krackhardt 1990) or as conduit-like instruments granting access to resources such as knowledge (e.g. Borgatti and Cross 2003). In this article, the term ‘network’ is used in the context of ‘network organizations’. Following the literature on network organizations (and organizational networks), but keeping in mind that the term ‘network’ is first and foremost an analytic convenience and ‘less a description of any particular form of association’ (DiMaggio 2001a, p. 237), ‘network organization’ shall here be understood as a specific organizational model distinguishable from other organizational forms such as hierarchy/bureaucracy and market through its emphasis on reciprocity and collaboration rather than authority or competition (e.g. Powell 1990).Footnote 1 From the theoretical perspective of this paper, it is ultimately the particular way of coordinating (productive) activities associated with ‘network organizations’ that is of interest, rather than the entities or properties that might or might not deserve the label ‘network’, ‘organization’, or ‘network organization’ according to any of the many definitions available. In this sense, the concept of network organization is also somewhat independent from the theoretical division often drawn between inter- and intra-organizational networks. As ‘new logic of organizing’ (Powell 2001, p. 35) that impacts how ‘work is organized, structured, and governed’ (ibid), it may not only transcend the theoretical borders commonly drawn around organizations. This ‘new’ logic of organizing may, as will be argued, actually call the suitability of distinctions such as employee/organization and intra-/interorganizational into question.

In the literature on network organizations (and organizational networks), networks are usually the explanandum (see also Carpenter et al. 2012) and conceptualized as the answer to certain demands, especially current environmental demands (e.g. Miles and Snow 1992; Sydow and Windeler 1998; Starkey et al. 2000; Sydow 2003; see also Dijksterhuis et al. 1999), such as the often mentioned need for greater flexibility. Thus, in contemporary management discourse ‘network organizations’ are often advocated as the most efficient managerial solution for coordinating productive activities (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005). Commonly assumed in such approaches is that networks consist of ‘actors who make contacts’ (Czarniawska 2004, p. 781). Thus, according to this perspective, actors come first, i.e. ‘there first have to be actors before networks can come into being’ (Lindberg and Czarniawska 2006, p. 294). This assumption is problematic, because it postulates and ascribes priority to presumably pre-existing entities (individuals or organizations). Further, ‘trust’ defined as a ‘type of expectation that alleviates the fear that one’s exchange partner will act opportunistically’ (Gambetta 1988, p. 217 cited in Bradach and Eccles 1993, p. 282)Footnote 2 is commonly seen as ‘control mechanism’ (Bradach and Eccles 1993) specific to and characteristic of the network form of organization.

The concept of trust played a major role in the theoretical development of the construct of the ‘network organization’ through contributing to possibilities of differentiating this form from other organizational forms (bureaucracy and market).Footnote 3 Coase’s (1937) work on ‘The Nature of the Firm’ is usually credited for initiating the debate on the relationship between different organizational forms, i.e. markets and, in Coase’s parlance, firms (bureaucracies/hierarchies) (see e.g. Bradach and Eccles 1993; Powell 1990; DiMaggio 2001b). By pointing to the existence of other mechanisms organizing transactions than price, namely, the ‘directions of an entrepreneur’, Coase introduced what should later be termed the ‘dichotomous view’ (Podolny and Page 1998) in which market and firm (bureaucracy) featured as ideal types of organizing productive activities. Williamson’s (1975) transaction cost economics developed this thought further and set the stage for the development of the ‘continuum view’ (ibid) in which the existence of other forms of organization than market and bureaucracy was acknowledged only as hybrids located on a continuum between the two ideal types (see e.g. Powell 1990; Bradach and Eccles 1993; Podolny and Page 1998; DiMaggio 2001b; Provan and Kenis 2008; Antivachis and Angelis 2015). Today, a large number of scholars (e.g. Ouchi 1980; Thompson 1993; Rhodes 1996; Podolny and Page 1998; Starkey et al. 2000; DiMaggio 2001b; Baudry and Chassagnon 2012; Castells 2004; Halinen and Törnroos 2005; Demil and Lecocq 2006; Cristofoli et al. 2014; Antivachis and Angelis 2015) share an alternative perspective from which the network form of organization is seen as an autonomous form of organization with its own logic (Powell 1990).Footnote 4 In this view, the ‘network logic’ and the ‘properties of the parts of the system’ (i.e. the network organization) is characterized by the kinds of interaction that take place among the parts of the system (Powell 1990, p. 301). And, it is argued, because those kinds of interactions are reciprocal, preferential and mutually supportive, they result in trust (ibid)—now commonly taken to be the central coordination mechanism specific to and characteristic of ‘network organizations’.Footnote 5

Contrary to this assertion, this paper argues that the prime focus on trust is ill-suited for understanding the coordination of everyday activities in network organizations and calls for a reconsideration of this assumption in research on network organizations.Footnote 6 Whether trust is a substitute for or complements other coordination mechanisms is an ongoing debate in the broader field of trust research (Skinner et al. 2014). With its emphasis on the (presumed) economic benefits of trust (in contrast to price or authority), the literature on network organizations tends to share the ‘substitution perspective’ (see also Costa and Bijlsma-Frankema 2007) and usually approaches trust as the coordination mechanism in network organizations. However, empirical findings do not substantiate the substitution view (Costa and Bijlsma-Frankema 2007; Skinner et al. 2014). Apart from that, trust as a single concept is unlikely to offer adequate explanations of such multi-faceted and complex configurations as (network) organizations (see also Grandori 1997)Footnote 7—ascribing an overly potent role to trust may even lead to a neglect of other important governance mechanisms. Relatedly, such a focus on trust can contribute to a disproportionately positive image of network organizations. Although there is an increasing number of studies in the broader area of trust research that challenges one-sided views on trust (Siebert et al. 2015), the ‘truism that trust is always, in and of itself, something which is good and desirable’ (Skinner et al. 2014, p. 218) seems still dominant—even more so in the literature on network organizations.Footnote 8 This bright picture of trust potentially veils less positive aspects about the coordination of everyday activities in network organizations.

For these reasons, this study does not follow other studies on network organizations in assuming an exclusive or prime role of trust in the coordination of everyday activities in ‘network organizations’. Grounded in an empirical case of an organization which describes itself internally and externally as ‘network organization’, this study instead seeks to further problematize the role ascribed to trust and combines Schatzki’s (e.g. 2008) practice-based theory and a Foucauldian understanding of governingFootnote 9 to contribute to a more differentiated understanding of the coordination of everyday activities in ‘network organizations’ in order to enhance our understanding of the constitution of this way of organizing productive activities. By focusing on how the ‘network organization’ and its subjects are ‘produced’ in power-infused practices, this study provides insights into the complexity of mechanisms involved in such organizations. Drawing on Schatzki’s (e.g. 2008) sophisticated conceptualization of practices as nexuses of doings and sayings, organized by and linked through understandings, rules, and teleoaffective structures,Footnote 10 allows to provide a systematic exploration of the ‘integrative’ practices prevalent in the empirical organization and to account for the role of ‘affectivities’ (emotions, or moods) in organizing practices—an important point often overlooked by studies on governmentality. Additionally drawing on Weiskopf and Loacker’s (2006) Foucault-inspired work on ‘technologies of modulation’ allows to trace and depict the multiple ways in which the ‘appropriate individual’ (Alvesson and Willmott 2002) is produced in the networked economy and organization. Thus, in contrast to a ‘rationalist perspective’ on governance (Ezzamel and Reed 2008) which ‘highlights calculated intent and efficiency maximization’ (p. 599) when theorizing the coordination of productive activities, this study proceeds from what has been termed a governance as ‘governmentality perspective’ (Ezzamel and Reed 2008), or an ‘analytics of government’ (Dean 2010) that is ‘concerned with the specific conditions under which entities emerge, exist and change’ (p. 30). Such a perspective highlights how any stabilized form (be it actor or organization) is a contingent product of power-infused practices. The analysis thus brackets questions of economic efficiency of organizational forms and focusses instead on the practices producing ‘network organizations’.

2 The constitution of network organizations and their members: the organization of social practices and technologies of modulation

2.1 The constitutive force of social practices

The emphasis on practices instead of individuals (or structures) allows studies based on practice theories to readdress the constitution of phenomena such as organizations or individuals rather than granting such phenomena ontological primacy and treating them as given.Footnote 11 Although ‘practices’, as for example ‘control and coordination practices’ (Rometsch and Sydow 2006) have been referred to in the literature on networks, practices have regularly been described merely on the surface level in this stream of literature (e.g. Johnston and Lawrence 1993; Gombault 2006). Though these studies are undoubtedly of theoretical value, merely describing practices on a surface-level is not sufficient from perspectives adhering to a practice-based ontology (Rasche and Chia 2009; Nicolini 2012) and represents a rather ‘weak approach’ to practices (Nicolini 2012, p. 13). Despite the remarkable diversity of practice-based approaches (Miettinen et al. 2009; Nicolini 2012), their common emphasis on practices suggests ‘to get close’ (Rasche and Chia 2009), because exploring some phenomenon from this perspective means exploring the everyday doings and sayings which bring this phenomenon into being. Following this ‘strong programme’ (Nicolini 2012, p. 13) of practice-based theories, I understand practices as fundamental to the fabrication of the social and consider social reality as ‘fundamentally made up of practices’ (Feldman and Orlikowski 2011, p. 1241). Seen from this perspective, social practices are productive of the subjectivities and identities of actors in network organizations. It is through participation in practices that actors become who they are (May 2001; Schatzki 2008).

2.2 The organization of social practices

I mainly draw on Schatzki’s well-developed approach to social practices. In Schatzki’s work on social practices, ‘any practice opens a dense field of coexistence embracing its participants’ (2008, p. 186) and thereby automatically establishes orderings among these participants (ibid, p. 195). Thus, participants in a practice are not equal, but rather ‘separated, hierarchized and distributed’ (ibid, p. 196). Sociality or the hanging-togetherness (Zusammenhang) of social lives opened in a practice is ‘essentially an interrelating of lives within practices’ (ibid, p. 180) and to a large extent ‘organized around a range of subject positions’ (ibid, p. 198). Actions of practices, i.e. doings and sayings pertaining to specific practices are organized by understandings, rules and teleoaffective structures. The understanding of a practice linking its respective actions consists of the ability or know how to carry out, identify and prompt or respond to this specific practice (ibid, p. 91). For example, the understanding of explaining prompts a local to explain (respond) the way to a tourist asking (prompt) for directions to a place particularly difficult to find. The actions he performs while explaining the way to the tourist are identifiable as such by the tourist (ability to identify). While understandings mostly organize ‘dispersed practices’ (practices widely used across different sectors of social life such as explaining, examining, questioning), rules and teleoaffective structures usually link integrative practices (‘the more complex practices found in and constitutive of particular domains of life’ (ibid, p. 98)) as for example business practices. Rules are explicit formulations such as principles, precepts, or instructions that people refer to when carrying out a practice (ibid, p. 100). While rules governing behavior must be explicit, teleoaffective structures do not have to be. Teleoaffective structures refer to teleologies (hierarchized ends, purposes, projects, tasks etc.) and affectivities (emotions, moods) expressed by the actions of a practice. While the teleoaffective structure of some practices is rather concerned with teleology (e.g. the aim of business practices to generate monetary value), other teleoaffective structures are rather geared towards affectivities, e.g. rearing practices (ibid).

2.3 Technologies of modulation

Schatzki’s sophisticated account of the organization of practices allows a systematic analysis of integrative practices and highlights their affective aspects. But how can we understand the ways in which participants of nexuses of practices take on the subject positions opened up there within? I will draw on the concept of ‘technologies of modulation’, i.e. technologies of responsibilisation, contractualisation and employabilityFootnote 12 (Weiskopf and Loacker 2006) to explore the multiple ways in which the ‘appropriate individual’ (Alvesson and Willmott 2002) is produced in the networked economy and organization. Basically, technologies of modulation refer to the diverse ways in which subjects are constituted in power-infused practices in the context of the ‘post-disciplinary regime of work’ associated with the networked organization and society. One of the central insights highlighted by this concept is that the mode of organizational subjectification has shifted in post-disciplinary regimes of work (Weiskopf and Loacker 2006; Weiskopf and Munro 2012). In contrast to ‘disciplinary modes of subjectification’ where subjects could proceed in preset stages towards some more or less stable image as for example some image of an ideal type worker, ‘post-disciplinary regimes’ demand constant reinvention of the self along with imagined potential requirements. Deemphasizing education or traditional career progression in terms of enclosed career stages and highlighting flexibility and the continuous need to adapt to changing requirements instead, post-disciplinary modes of subjectification call for the continuous modulation of the self rather than a molding of selves towards more or less stable models (Weiskopf and Munro 2012).

The concept of the technologies of modulation is based on a Foucauldian understanding of governance, or better governmentality (see Ezzamel and Reed 2008 for a review of different understandings of governance). Governance understood in the sense of governmentality is ‘a form of power referring to the ‘conduct of conduct’ (Foucault 1980, p. 221)’ (cited in Du Gay 1996, p. 55) that is ‘intimately concerned with “subjectification”’ (ibid). Put differently, governmentality is an attempt to shape the field of possible actions (e.g. Dean 2010) and of possible ways of being. From a governmentality perspective, rationalities of power, as for example the ‘post-disciplinary’ or ‘projects-oriented justificatory’ regime (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005) associated with the network form of organization ‘involve the construction of specific ways for people to be’ (Du Gay 1996, p. 55). Technologies of modulation in turn permit to trace the processes of subject formation through which subjects take on these ways of being and highlight the forcefulness of such processes. It is through this understanding of ‘governance’ as governmentality that we can see how actors and network organizations are constituted through social practices and how this very process of constitution is what governs (network) organizations and their actors. I will explain the single technologies of modulation (responsibilisation, contractualisation and employability) on the example of the case study.

3 Methodology

Understanding how phenomena is constituted in social practices necessitates to ‘get close’ (Rasche and Chia 2009). Consequently and in line with the suggestions made by practice-based scholars (e.g. Schatzki 2008, 2012; Nicolini 2009, 2012) an ethnographic participant observation was conducted within the framework of a case study. The participant observation was carried out in company ‘X’, an organization which describes itself both internally and externally as a ‘network organization’. The selection of the case followed the idea of theoretical sampling (Eisenhardt 1989), aiming at choosing what has been called an exemplary or key case (Thomas 2011). Since the ‘keyness’ of the research subject lies in its ‘capacity to exemplify the analytical object of the inquiry’ (Thomas 2011, p. 541), an organization which is described by its members as network organization was chosen. While this argument about the selection of the case may sound weak from an essentialist point of view, arguing that ‘properties’ or ‘characteristics’ of the organization should be presented as proof qualifying this entity as network organization, giving such ‘proof’ would be against the assumption ground of practice-based studies. Seeing organizations ‘through the practice lens’ (Orlikowski 2000) urges to focus on the emergence of such phenomena rather than on their presumable properties. From this perspective ‘organizations have neither nature nor essence; they are what people perceive them to be’ (Czarniawska-Joerges 1993, p. 9). Members of company X (henceforth: ‘Xler’) frequently contrasted ‘their’ way of organizing, working and being to the ways in which their customers (mostly medium-sized, well-established German companies) operated—sometimes they also referred to their previous employers to distinguish their company and themselves from other organizations and their members. In this context, they regularly portrayed these other companies as ‘rigid’, ‘bureaucratic’, ‘ineffective’, ‘hierarchical’ and ‘rule-governed’ while describing company X as being more or less the opposite and best described as network-like. By being network-like, members of this organization usually meant as little formal rules as possible, as little authoritative behavior and hierarchy as possible and an emphasis on flexibility, and individual ‘freedom’ and ‘responsibility’. During the research process it turned out that the value of this case may not lie in its ‘capacity to exemplify the analytical object of the inquiry’ (Thomas 2011, p. 541), but rather in its capacity to ‘falsify’ the assumption that trust is the main coordination mechanism in network organizations. As Flyvbjerg (2006) points out drawing on Popper’s (1959) ‘black swan’ example: ‘The case study is well suited for identifying “black swans” because of its in-depth approach: What appears to be “white” often turns out on a closer examination to be “black”’(p. 228).

Founded in 1996 as a spin-off of a research institute, the fast-growing German-based consulting company today employs more than 2500 people and achieved an annual turnover of more than a quarter billion in 2013. It provides consulting services in 11 countries, mainly in the automotive, mobile communications and aviation sectors. The respective subsidiaries of company X (divided either by country or sector) were often said to be more or ‘less X-like’, meaning more or less ‘network-like’. I conducted the participant observation as part-time employee over a period of 7 months in subsidiary ‘A’ of company X. Subsidiary A was not considered to be very ‘network-like’ by the members of company X (though possibly still more ‘network-like’ than other companies). However, this subsidiary cooperated very closely with subsidiary ‘B’ which was regularly cited as being very ‘network-like’. The two subsidiaries were in the same building, used the same rooms for breaks and work, had the same customers, cooperated in numerous projects and one of the directors of subsidiary B was also director of subsidiary A. This setting facilitated a comparison of how working and being in a ‘network’ organization should or should not be according to its members. While B was financially successful and had a good reputation in company X, this was not the case for subsidiary A.

The participant observation enabled to ‘get close’ (Rasche and Chia 2009) and beyond a ‘weak approach’ (Nicolini 2012) to practices (see also Schatzki 2008, 2012). During the participant observation (in total more than 530 h in 68 days spread over 7 months), fieldnotes were taken (in total 30 pages of single spaced, typed text) and informal interviews conducted. The participant observation included working at the company, participating at company events, assessment centers and leisure time activities (e.g. lunch breaks, cigarette breaks, going out for dinner, coffee or drinks, visiting the Christmas market, playing billiards). Members of the organization were informed about the study. In fact, writing a doctoral thesis on network organizations was listed as main job description in my employment contract with company X (for which I was allowed to spend 70 per cent of my working time). Thus, whenever I met new people at company X, I talked to them about the study (understanding how network organizations work on the example of company X) when explaining what I did at company X. Additionally, three semi-structured interviews (one with an employee of subsidiary A, two with members of subsidiary B), each lasting between one and 2 h were carried out to complement the impressions gained during the participant observation. The interviews were fully transcribed verbatim and coded with in vivo and constructed codes using the software ATLAS.ti (version 7.5.7). While the interviews were helpful for checking on the experiences made during the participant observation and crucial for making some of the emergent themes more explicit thus also augmenting my reflection on these matters, the direct experiences gathered by working in this company, participating at company functions, and meeting some of the company’s members in recreational time (as was common in this company) are indubitably at the core of the empirical base of this study. What Nicolini (2009) remarked regarding a specific interview technique holds true for the application of interviews in practice-based studies more generally: Interviews should be seen as an ‘addition to the toolbox of ethnographic participant observation’ rather than as ‘a shortcut for doing away with it’ (p. 199).

The analysis was an iterative process going back and forth between theory, field and empirical material. Since ‘empirical material never exists outside perspectives and interpretative repertoires’ (Alvesson and Kärreman 2007, p. 1266), I followed van Maanen, Sorensen and Mitchell’s (2007) suggestion and tried to give primacy to both theory and evidence during the analysis. Thus, rather than following a strictly deductive or inductive logic, I (inevitably) framed the experiences gained during the participant observation with theoretical concepts and ideas I was already familiar with (as for example ideas on network organizations) and tried to adopt and augment a reflexive stance towards these ideas (for example concerning the role of trust in such organizations) and my expectations about the empirical setting (which were at the beginning rather positive) and my interpretations of the experiences made during the participant observation (that have been quite ambivalent). The aim of the analysis is to provide deep insights into the constitution of this specific ‘network organization’ by focusing on the organization of working and related integrative practices in company X, pointing to the possible ways of being opened up by these practices, and carving out the various mechanisms involved in the processes of subject formation. The analysis is therefore structured around the main theoretical themes and concepts discussed above.

4 Analysis

4.1 Formal rules and regulations

Striking but rather unsurprising about the way work was organized in company X was the explicit avoidance of formal rules and regulations. In company X, rules were associated with bureaucracy (which was perceived as inefficient, useless and rigid) and thus perceived as inept for a network organization. This finding is in line with the widespread assertion that network organizations differ from more bureaucratic organizations by their little use of formal rules (see e.g. Bradach and Eccles 1993). However, referring to formal rules drawn from the institutional context (e.g. employment protection legislation) was on some occasions not only seen as inept, but even taken as assault by some of the organizational members. For example, when student assistants working at company X addressed their right to holiday entitlement, some of the organizational members felt that this claim was very ‘ingrate’, because, from their point of view, student assistants at company X already had so many benefits (e.g. good wages, flexible working hours, social events, etc.) which were seen as more than compensating legal or other formal rights. According to one of the interviewees, some Xler took such claims personal and reacted quite defensively (i.e. asked student assistants to refrain from making such claims or leave the company). Other occurrences at company X also made clear that referring to formal rules and regulations was only acceptable when a third party involved demanded certain formal procedures. Otherwise formal rules could not be referred to—referring to rules was simply not an option for a competent Xler and, as will be shown shortly, run counter to their understanding of desirable ways of being.

4.2 Being a competent Xler and the technology of responsibilisation

In company X it was understood that a competent Xler does not need formal rules (e.g. employment protection legislation) to take care of him-/herself. A competent Xler is self-reliant. A successful, self-employed entrepreneur enthusiastic about working at company X. Becoming such a successful Xler was the main telos, the main aim, of working at company XFootnote 13 and largely organized the practices participants’ actions. Besides leading to an avoidance of formal rules and regulations, this telos organized work activities in various ways: How work was accomplished was irrelevant, what counted were results; Xler were responsible for their career; a call for leadership/guidance was considered inept. Generally speaking, Xler were assumed to be responsible for their own (private and professional) fate for they had the privilege to make use of the ‘freedom’ provided by the ‘playground’ (Spielwiese) that company X offered—on the condition that they acted ‘as if it (company X) was their company’. This emphasis on freedom and self-responsibility exemplifies what Weiskopf and Loacker (2006) term technology of responsibilisation. As one of the technologies of modulation which produce ‘the flexible and governable subject demanded by the post-disciplinary regime’ (ibid, p. 14), responsibilisation ‘creates individual units that are responsible for carrying out a task and reaching predefined goals’ (ibid, p. 15).Footnote 14 While some Xler did see this freedom to control one’s self (in a predefined way) as privilege, most were aware that ‘this isn’t something for everybody’. Some stated that they felt left alone and would appreciate some guidance or somebody who ‘cares’.

4.3 Affectivities of proud and fear

However, taking pride in being a self-reliant and successful Xler was the appropriate affectivity to be espoused in company X. Thus, Xler were (supposed to be) constantly in a good temper (as they were seen as responsible for their fate, being in a bad temper might signal some kind of personal failure, or worse mean that they actually do not fit to company X). At the beginning of the participant observation was an instance in which I was asked how I was and answered not so well. The consternated face of my interlocutor made me aware that this had been a faux pas. From then on I paid extra attention to espoused affectivities and it became clear that not being in a good temper was only allowed behind closed doors in the ‘backstage’ regions (Goffman 1959) of company X. Thus, by largely inhibiting the exhibition of negative affectivities in the public spaces of company X, the affectivity of proud impeded possibilities to openly voice critique about company X. I only came across one (!) story about an instance of openly voiced critique in subsidiary B during the participant observation. This story was about an Xler who had written ‘unfriendly’ mails and was labeled a ‘virus’ who ‘infects the others—especially the neophytes’ by the Xler who told me this story. I was not told what exactly the content of these ‘unfriendly’ mails were or whether the claims this person made were justified or not. I was only told that the ‘virus’ had left the company after an interlocution with one of the founders that had ‘not been unanimous’.

Since voicing critique about company X openly was inhibited by the affectivity of proud (to be displayed), it was usually ‘behind closed doors’ where the negative aspects of the telos of self-reliance and self-responsibility were discussed. This telos was also manifest in subsidiary A, despite the fact that subsidiary A was considered to be less X-like. Here, the ideal of a competent Xler became most problematic and other affectivities governing practices participants’ actions came to light. Subsidiary A was considered to be less X-like especially because of the autocratic and paternalistic leadership style of its team leader (called ‘Papa’ by employees of the subsidiary). In this context the discourse of being ‘free’ and the sole person responsible for one’s fate had little room for materialization. Rather, employees often felt suppressed and treated unfair. One of the interviewees stated that what structured her everyday activities in this subsidiary was the constant fear of being fired. This fear was shared by others at the subsidiary and from my experience working at this subsidiary, it seemed justified. The affectivity of fear (of being fired) did indeed structure a great deal of everyday activities. Employees in this subsidiary came to work when they were ill, executed projects in ways the team leader judged right but they strongly perceived as wrong, worked long hours and always worried about how to legitimize their work.Footnote 15 To reduce this conformity of members of subsidiary A with what they felt was expected of them to material concerns (e.g. worries about their economic independence) would ignore the ‘symbolic’ aspects (Collinson 2003) of such insecurities. The fear of being fired involved much more than a fear about losing one’s monthly income. Given that members of subsidiary A also strived for becoming competent Xler,Footnote 16 the fear of being fired involved an existential fear about not being able to achieve this goal. Connected to this, such worries also extended to a projected future in which they saw their employability (a point to be taken up shortly) in general at risk.

4.4 The telos of generating revenue

Besides the fear of being fired (subsidiary A) and in line with the aim of becoming a competent Xler (subsidiary A and B), generating revenue for company X by selling one’s consulting services to external customers was an important telos structuring work-related activities in company X. In case of subsidiary B those customers were usually medium-sized companies of the German automobile sector and customer relations were long-term oriented. The aims of the company (owners) and (other) Xler converge in that both subject positions aimed at generating revenue by selling ‘manpower’ to these customers. Thus, generating revenue was another important telos structuring working and being at this company. Typically, Xler were self-employed and usually they had cooperation agreements with company X only.Footnote 17 Every year, Xler negotiated target agreements with their ‘mentor’ specifying how much revenue should be generated next year, what the next steps will be (for example: write your first offer, sell so and so many ‘man-hours’ next year) and what they will do concerning ‘special topics’ (mainly participating at or organizing internal projects or events). Only aims were defined in such target agreements. How these aims were to be achieved remained open and under responsibility of the individual Xler. Achieving the target revenue was, as I was also told in the interviews, a very important goal.

Since customers also paid well for the execution of relatively simple tasks such as filling in Excel sheets with given data or crafting PowerPoints for presentations already designed (‘Folien malen’), achieving the target revenue was also possible for entrants who just finished their university degree. During their first days working at company X, entrants were usually send to their first ‘Nasentermin’, a meeting with the customer in which the customer could agree or disagree with the ‘consultant’ presented to him/her for the execution of an order already signed or to be signed shortly. While the ‘projects’ to be executed were relatively simple, the situation required persons with a certain appearance and the social skills necessary to work for the customer (e.g. good self-presentation, communication skills). This explains why being presentable to a customer was one of the main criteria for HR selection (besides being congenial and ‘intelligent’) and why professional expertise was less important in this process.

4.5 Working and employability

The telos of generating revenue structured what was considered appropriate work for a Xler. Though working in a rather unpretentious project was considered appropriate as long as sufficient revenue was generated, presenting this project as demanding was important for various reasons and different subject positions. Since Xler, including the entrants, aimed at becoming competent Xler, they needed to gain relevant capabilities. Such capabilities were gained and demonstrated through the projects in which one worked and recorded in a consultant profile (‘Beratersteckbrief’). The consultant profile, presented to customers searching for some service, is a materialization of what Weiskopf and Loacker (2006) term technology of ‘employability’, another technology of modulation producing the governable subject in post-disciplinary regimes. As the authors point out, the technology of employability has a double effect. First, it creates ‘new fields of visibility’ which introduce ‘objectifying effects’ (ibid, p. 16), i.e. rather than emphasizing education or traditional career progression in terms of enclosed career stages, consultant profiles highlighted project experience and competences (‘methods’). Second, employability reframes the comparatively high uncertainty accompanying short-term engagements as a challenge—one may even say as an opportunity—rather than a threat (ibid, p.16). Since becoming a successful Xler entailed having demonstrated certain competences (e.g. having implemented a process optimization during a project using the ‘method’ Six Sigma), working in projects rather than long-term engagements was understood as opportunity for increasing one’s employability rapidly. Projects conducted were recorded in one’s consultant profile, materializing one’s employability. However, one can never be ‘employable enough’ (Cremin 2010) in the post-disciplinary regime of work. Since employability is always concerned with beliefs about possible but fundamentally uncertain future requirements, the pursuit of maintaining or increasing one’s employability never ends (see also Weiskopf and Munro 2012). There is no definite or defined set of capabilities that makes one a competent Xler and employability is no reachable end state. Further, capabilities as for example being able to conduct a process optimization using the ‘method’ Six Sigma which are valued today may lose their attractiveness once a ‘better’ or simply more fashionable method appears. The same holds true for the products, branches and techniques one specialized in. Xler were encouraged to find new projects for themselves (‘just do what you fancy! Who prevents you from doing so? Just do it!’) and expected to take responsibility for the routes they chose. The image of the ideal type worker here is, if still present, flexible and not stable. The same holds true at the organizational level: As leading figures of company X as for example one of the founders emphasized in their speeches at company events, the overall company strategy was to have no strategy. Having a strategy was seen as mistake, because, so the argument runs, a strategy makes you inflexible to unforeseeable future requirements. As an HR responsible of subsidiary B put it:

It is possible that we may be doing completely different things tomorrow…we also always only say when we say what does company X do? Today we do this. What we will do tomorrow? No clue. (…) We want to invent. We continuously reinvent ourselves. We try things. Much of this doesn’t work out, some of this stays.

This ‘strategy of non-strategy’ forecloses any possibility for the development of a stable image of an ideal type worker and Xler were expected to be thrilled about the ‘opportunities’ offered by company X which demanded constant reinvention of itself and consequently also of its members. Uncertainties accompanying such constant reinvention are veiled under the positively connoted mantra of flexibility (Weiskopf and Loacker 2006).

Somewhat paradoxical about this never-ending quest for employability and the telos of generating revenue is that clients expect consultants already experienced in a certain domain while consultants usually aim at furthering their repertoire of capabilities. This is especially the case for entrants who, due to their early career stage, do not dispose of a wide range of project experience. Thus, to boost one’s reputation as competent Xler and one’s consultant profile, simple tasks (‘projects’) were presented as more complex and demanding. Since the partners and other Xler who had acquired the projects needed Xler to carry such projects out (they gained a commission), they also presented rather undemanding tasks in an attractive way. It was understood that claims about the complexity of one’s projects were not responded to by critical questions, but rather used as occasion for presenting one’s own project in a favorable way. During the participant observation, I regularly listened to such presentations (in form of informal talks between the colleagues) on Fridays when the consultants ‘came in’ (consultants often worked at the customers’ office from Monday till Thursday) and I admit that I was impressed by the presumable complexity of the projects even entrants carried out. I wondered how these people managed to execute such projects when they just came from university and did not have any noteworthy practical experience. It took me a while and a lot of conversations (including the interviews) to realize that projects were usually far less complex or demanding than they were presented.

4.6 Grounding neophytes and goal-orientation

Though presenting one’s work and self in such a way was generally considered appropriate, there were limits to how far one could go—and in the end the aim was not to appear as successful Xler but to become a successful Xler. One of the HR managers complained that as soon as entrants started working for company X, ‘they at one go feel like they are something special. Just because they signed here…but the fact that you now own three suits and ordered caviar doesn’t make you a hero’. To ‘ground’ the entrants and to show them ‘what they can’t yet do’ or that they ‘can’t anything, but that this isn’t so bad, because that’s why they’re here’, entrants were send to a ‘bootcamp’ organized by the company after having worked for approximately 6 months at company X. This 4 days bootcamp was located in a shutdown ore mine. The location was selected deliberately to ‘ground’ the participants (one big room with two cold showers, two toilets and three sinks where all 25–30 participants sleep on mattresses) and sharply contrasted with the luxurious hotels the consultants were used to in their daily working lives. In the bootcamp, participants were divided in three groups and each group was given the task to prepare a presentation on a defined topic to be evaluated by one of the founders (the one that appeared to be the most ‘legendary’ and charismatic)Footnote 18 at the last day.

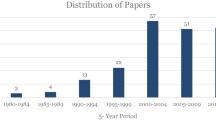

Besides ‘grounding’ the participants, another major aim of the bootcamp was to show them how to work and what goal-oriented working means in company X. Pressure was deliberately executed by two charts (see Fig. 1), fortified by the pending presentation to the founder and, as I was told in the interviews, made even worse by colleagues (who, as I was told by one of the organizers, ‘mauled’ each other after a while). After the presentation had been hold and the winner chosen, participants were encouraged to reflect on their experience at the workshop. In group discussions led by the organizers of the bootcamp, they came to the conclusion that all the pressure they experienced was in fact self-induced. As one of the organizers put it, the bootcamp has something ‘mind-augmenting’ and people notice that the ‘performance pressure is not extrinsic, but intrinsic and that’s how you see that you can put yourself under pressure and that you can make yourself incapable of action’. Because, in the end what counts is the presentation to the founder. All the rest (e.g. the charts) should be recognized as irrelevant. For example: worrying about scoring well at the chart on the left (see Fig. 1) is the wrong goal and only leads to unnecessary and distracting (‘self-induced’) pressure. The only thing that counts is the final presentation to the founder. Transferred to the usual work-setting: The only thing that counts is the final service provided to the customer.

Charts used at the bootcamp to depict the progress of the three groups. This figure was drawn by one of the bootcamp organizers. I rewrote the labels for reasons of readability and anonymized the name of the founder. The label of the axes of the chart on the left show progress in time as judged by the bootcamp organizers. The vertical axes which indicates the progress was deliberately left undefined by the organizers of the bootcamp. The lines represent the respective progress of the three groups. The bar chart on the right depicts the time already passed and still left until the presentation to the founder

4.7 Forms of employment and contractualisation

Structuring work by goal-orientation has been associated with the technology of contractualisation (Du Gay 1996), another technology of modulation (Weiskopf and Loacker 2006) which ‘enterprises up’ institutions or individuals. The technology of contractualisation consists in contractualising relationships (in the case of company X mainly traditional employment relationships) in such a way that a distinct performance is assigned to a specific unit (in this case the carrying out of a specific project to an individual Xler) who is then responsible for the carrying out and outcome of this assignment (Du Gay 1996). Literal contractualisation of the employment relationship in terms of self-employment was the norm and considered appropriate for a successful Xler. I regularly heard the claim that one needs to be self-employed to ‘be on par’ with one’s superiors and the partners. This talk about ‘being on par’ with ones superiors and partners resonates the discourse of the ‘projects-oriented justificatory regime’ (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005) in which hierarchy is rejected as a form of domination (p. 165). In line with the telos of becoming a successful Xler and the associated emphasis on self-reliance, being told what to do by another person was considered wrong. A competent Xler should be capable of making his or her own decisions. One of the interviewees compared having a superior with being a dog on the leash of his master. He preferred to put himself on the leash. Being self-employed was considered to enable Xler to do so and was thus the expected option to take in company X.

However, there were also some exceptions. While work relationships have been literally contractualised in the case of the ‘self-employed employees’, some Xler had regular employment contracts. But since employment contracts were also categorized as formal rules and regulations and thus considered inept for a network organization like company X, referring to such contracts was seen as unacceptable. Thus, a ‘reconstruction of social relations (…) in terms of “contract”’ (Weiskopf and Loacker 2006, p. 15) was also possible (and present) even if an Xler had a traditional employment contract. It seems that continuous performance measurement, another feature of the technology of contractualisation (Weiskopf and Loacker 2006), was even more present in these cases. In subsidiary A for example, which was considered less network-like, most of the employees had regular employment contracts. Still it was expected that employees ‘pay off’. Here, the team leader was responsible for acquiring and allocating projects and the employees were responsible for carrying these projects out. As in subsidiary B, turnover was generated mostly through ‘external projects’, i.e. consulting services provided to external customers. Contrary to subsidiary B, employees seldom had direct customer contact. Instead, the team leader judged the quality of a service (usually a PowerPoint presentation) before the customer did. One of the teloi of working in subsidiary A was thus to deliver results that were likely to be judged positively by the team leader (and later by the customer). In combination with the affectivity of fear of being fired which structured the working practices in this subsidiary, any task or project was perceived as a test. This state of permanent performance evaluation was perceived as highly stressful by the employees of subsidiary A, especially because the projects were usually ill-defined and the evaluation criteria opaque and alternating. For example, I was asked to make a short version of a presentation on a change management tool to be included in some presentation of the range of services of subsidiary A which the team leader had doomed to be completely useless and ‘crap’ some weeks earlier.

4.8 Trust-based working hours

Working goal-oriented in subsidiary A basically meant being responsible for achieving an unknown and changing goal, usually under time-pressure (one of the team leader’s favorite slogans was ‘diamonds are formed by high pressure’). How much time was spent for achieving this goal was largely irrelevant (this was also the case in subsidiary B)—as long as the deadline was met. Working hours were not recorded or reported. The absence of an attendance recorder or the like and the use of so-called trust-based working hours (Arbeit auf Vertrauensbasis) was presented in a positive light by the team leader and others. We will not control how much you work, so the argument goes, because we trust you. In practice, employees of subsidiary A worked way more than the 8 h specified in their employment contracts. Working ten to 12 h a day (on average) was not uncommon for some of the employees and, though they felt it was weird, some said to feel bad if they had not made ‘so much’ overtime in a certain time-span. Again, employees are free to lead themselves as long as they act in the interest of the company (technology of responsibilisation) and achieve a pre-specified goal (technology of contractualisation), i.e. ‘pay off’. The drawbacks accompanied by responsibilisation and contractualisation are hidden under the positively connoted veil of trust.

4.9 Related integrative practices

Contractualisation and responsibilisation redefine the subject positions available in working practices and shift risk and responsibility from the employer to the ‘employee’—or better to the ‘entrepreneur’. Simultaneously taking on this responsibility and risk makes Xler entrepreneurial selves actively seeking to increase their employability through their engagement in projects. This raises the question why Xler would stay at company X when they became successful entrepreneurs (a question also addressed by the charismatic founder in his speech at one of the company events). One possible answer to this question is that being a Xler was not limited to being a participant of the integrative working practices at company X,Footnote 19 but also entailed being a ‘cool’ and ‘fun’ person. Partying was central to this company and employees regularly aimed at being the ‘jester number one’ (‘Spaßmacher Nummer 1’) at company events and other occasions. As several Xler told me and as I noticed during one of the assessment centers, ‘would I like to have a beer with this person’ was one of the three questions decisive for the outcome of the recruitment process (the others being: does this person make company X more ‘intelligent’ and can she/he be send to the customer tomorrow). The importance of partying and drinking alcohol together was highlighted by virtually everybody in this company I talked to during the participant observation and in the interviews. ‘Work hard, play hard’ was a slogan.

As Costas (2012) points out in her exploration of the ‘friendship culture’ in a management consultancy, such a strong incorporation of traditionally non-work related practices associated with leisure time into the realms of the company can lead to a stronger ‘integration of the overall employee self’ (p. 393). Though traditionally non-work related practices such as partying and drinking alcohol together have conventionally been approached as ‘forms of subversion, resistance, and escape’ (Costas 2012, p. 393), such practices can actually be interwoven with and stabilize the nexus of practices productive of organizations and their members. The main telos of partying and drinking alcohol together at company X was to fulfill the expectations about being good at socializing or ‘networking’. Partying was also very often used to present one’s self and to leave a lasting impression. Indeed, stories about drunken men (all the stories I heard featured men in the star role) who did something which was considered to be funny were told quite frequently and in admiring voices in the company setting. The names of these persons were known widely afterwards in company X. One such story that I heard several times during the participant observation and then again in the interviews was about an Xler who belonged to the group of the ‘important people’. This Xler was very drunk at an inauguration party of a new office building and partied so hard that he wrecked the new building. To my surprise (I had only been working at company X for some weeks), this was perceived as very cool and funny. Pictures of the demolished rooms were sent to colleagues who were not present at the inauguration party and then shown to each other at the other offices. It were such stories, but also other occurrences which made it clear for everybody: If you cannot party and (are not willing to) drink, you are out (this was also stated explicitly several times). Another occurrence at a ‘Methods Slam’ organized by company X also exemplifies the importance of being a good party person: The one who won the ‘Methods Slam’ (he received a trophy) was the one who was the most drunk (which was highlighted and celebrated again at the plenary meeting the next day).

When partying, Xler aimed at socializing and leaving an impression. It seems plausible that this aim was shared by the (owners of the) company. One of the owners stated at a company event that the owners do not see such events as a cost, but rather as an investment and as a gratification for the work of the Xler. For sure there was an interest in stimulating exchange and creating a bond between Xler. Connected to this, there was another story circulating about the reason for conducting these luxury events which goes beyond the immediate slice of integrative practices of the company to the more private spheres of the people associated with the company. It was said that the company events originated in the wish to show one’s family and friends why one spends so much time at company X. Thus, an Xler was always invited to bring their partner or some friend(s) to these company events to show them how ‘cool’ company X is and how much fun it is to be there. While this also encouraged Xler to recruit their own families and friends (which happened quite frequently), it underscores the affectivity of proud about working at company X that Xler were expected to feel and display.

5 Discussion

Considering the foregoing analysis, it is plausible to question the centrality of trust as coordinating mechanism specific to and characteristic of ‘network organizations’. In the network organization analyzed, the idea of trust was explicitly used to replace more traditional forms of control in case of the ‘trust-based working time’. Here, the positively connoted idea of trust veiled the drawbacks (e.g. working longer hours than specified in employment contracts) of post-disciplinary regimes of work. Besides this, trust was not a central theme in company X. It thus seems that trust rather belongs to the ‘grammar’ of the ‘projects-oriented justificatory regime’ (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005) and is perpetuated in managerial literature than being the central mechanism specific to and characteristic of ‘network organizations’.

Starting from practices rather than actors or their (presumably trustful) relations, the analysis demonstrated that a multiplicity of mechanisms contribute to the constitution of company X and its members, suggesting that this very process of constitution is a governmental process.Footnote 20 Specifically, it has been demonstrated how technologies of modulation (Weiskopf and Loacker 2006) such as contractualisation and responsibilisation redefine the subject positions traditionally made available in working practices and shift risk and responsibility from the employer to the ‘employee’—or better to the ‘entrepreneur’. Simultaneously taking on this responsibility and risk makes Xler entrepreneurs, always striving to fulfill the Sisyphean undertaking of continuously increasing their employability through their engagement in projects. The analysis thus illustrated a shift in the mode of organizational subjectification in post-disciplinary regimes of work (Weiskopf and Munro 2012): In contrast to disciplinary modes of subjectification where employees could proceed in preset career stages towards some more or less stable image of an ideal type worker, post-disciplinary regimes demand constant reinvention of the self along with imagined potential requirements. Deemphasizing education or traditional career progression in terms of enclosed career stages and highlighting flexibility and the continuous need to adapt to changing requirements instead, calls for the continuous modulation of the self (post-disciplinary mode of organizational subjectification) rather than a ‘molding’ of employees towards more or less stable models of ‘ideal workers’ (disciplinary mode of organizational subjectification) (Weiskopf and Munro 2012). In company X, this shift in the mode of subjectification somewhat built on a shift in the employer–employee relationship: By taking on the responsibility that contractualisation postulated, Xler affirmed the entrepreneurial identity that engages in the never-ending quest for employability (see also du Gay1996, p. 180). Contractualised relationships differ from traditional employment contracts where tasks to be performed are specified, but where employees are not responsible for the economic reasonability of the outcome of these tasks. Through taking on the responsibility for the execution and outcome of a project, Xler affirmed an entrepreneurial identity and thusly also contributed to the telos of the integrative working practice of becoming a successful Xler.

Moreover, the analysis highlighted the role of understandings, rules and teleoaffective structures in organizing integrative practices and structuring the practices participants’ actions. In case of company X, the teloi of becoming a successful Xler and of generating revenue were quite influential in structuring Xlers’ actions. These aims inhibited reference to formal rules and regulations (telos of becoming a competent Xler), structured what was considered appropriate work for an Xler (telos of generating revenue) and the manner in which this work was to be carried out (telos of becoming a competent Xler). Affectivities of proud and fear also played a central role in structuring the participants’ actions. Both affectivities worked against possible forms of resistance, thereby stabilizing the nexus of practices. While the affectivity of fear induced conformity through insecurities about existential material and symbolic concerns, the affectivity of proud largely inhibited the exhibition of negative affectivities in the public spaces of company X, making overt critique hardly possible for competent Xler or Xler aiming to become recognized as such. Apart from that, the analysis has shown how traditionally non-work related practices such as partying and drinking alcohol together which have conventionally been approached as ‘forms of subversion, resistance, and escape’ (Costas 2012, p. 393) can actually be interwoven with and stabilize the nexus of practices productive of organizations and their members.

6 Conclusion

Contrary to the widely shared assertion in the literature on network organizations and organizational networks, this paper argued that trust may not be the central coordination mechanism specific to and characteristic of ‘network organizations’. To contribute to a more differentiated understanding of the coordination of everyday activities in such organizations in order to enhance our understanding of the constitution of this way of organizing, this paper developed a practice-based understanding of governing ‘network organizations’ and gave deep insights into the complexity of mechanisms involved in the constitution of a specific network organization. In the specific case analyzed, trust played a rather marginal role in structuring practices participants’ actions. Trust was explicitly used to replace more traditional forms of control in case of the ‘trust-based working time’. Here, the positively connoted idea of trust veiled the drawbacks (e.g. working longer hours than specified in employment contracts) of post-disciplinary regimes of work. Besides this, trust was not a central theme in company X. Overall, my analysis suggests that trust rather belongs to the ‘grammar’ of the ‘projects-oriented justificatory regime’ (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005) and is perpetuated in managerial literature than being the central mechanism specific to and characteristic of ‘network organizations’.

To finish, I want to draw attention to some of the limitations and implications of this study and point to some potentially interesting routes yet to be explored. Though we may question the central role of trust in network organizations by a single in-depth case study, it is not possible to generalize on the specific coordination mechanisms on this basis. For example, the fierce refusal of formal rules and regulations prevalent in company X might be partly due to the company’s national context. The German context is marked by an extensive degree of formalization and this might lead to backlashes which might be less definite in other cases. Thus, the explanatory power of this study in terms of how specifically network organizations are governed is limited. Though generalizability has neither been my aim nor does this aim, in principle, seem achievable for me, I hope that some of the findings might be transferable to other cases and believe that a comparison with similar cases could lead to interesting insights into the rationality of such post-disciplinary regimes of work. As has been shown in this study, practice-based theories offer one perspective suitable for this undertaking for they do not presuppose how (network) organizations and their members are or function.

The flexibility that practice-based theories offer for exploring the outcome of diverse organizing attempts enables to meaningfully investigate assemblages that might not fall under established conceptual divisions such as intra-/interorganizational, or employee/organization. For example, in case of company X an employee was not necessarily classified as such by other Xler according to whether or not he/she hold an employment contract with company X. ‘Self-employed employees’ only held cooperation agreements with company X, but were treated and behaved like employees. On the other hand, a self-employed person in fact formally constitutes its own enterprise in Germany (and in this sense, company X is an Xler’s customer). Thus, seen in this light, a ‘self-employed employee’ is both an organization and an employee. Taken further, company X can in fact be theorized as both an intra- and interorganizational network. Such cases carry with them a kind of latent ambiguity and somewhat question the suitability of established distinctions and categories. In their influential review of the ‘network paradigm in organizational research’, Borgatti and Foster (2003) point to a ‘linguistic chaos’ in the research area of network organizations and organizational networks. While this claim is certainly comprehensible and some more ‘order’ (ibid) most probably desirable, it may very well be that we need different categories and distinctions to grasp current developments in attempts of organizing and ways of governing to see clearer.

Further, this study mainly problematized the centrality ascribed to trust as governance mechanism in the literature on network organizations, but left the presumed neutrality of ‘trust’ largely unquestioned. However, as this study hinted at in case of the trust-based working hours, ‘trust’, when explicitly appealed to in praxis, is itself a form of exercising power. As part of the ‘grammar’ of the ‘projects-oriented justificatory regime’ (Boltanski and Chiapello 2005), the very discourse of trust may be used deliberately to veil drawbacks of post-disciplinary regimes of work. As Skinner et al. put it, ‘the very language of trust may itself contain within it a sinister potential as deliberately engineered performative acts’ (p. 220). In line with Skinner et al.’s (2014) call for investigating the underexplored use of the ‘discourse of trust’, I suggest that future studies should focus on empirical cases of ‘network organizations’ in which this discourse is more consequential, to help us to see and understand the downsides of this concept—a concept that has been perpetuated and left unquestioned for too long in theoretical debates on the governance of network organizations.

Notes

These terms have been used in many different ways by several authors. There is no common definition (see also Antivachis and Angelis 2015).

Trust has been defined in different ways highlighting different facets of the phenomenon. I follow McEvily et al.’s (2003) suggestion to decide for one of the many definitions of trust and apply it consistently throughout this paper.

Podolny and Page (1998) for example argued that the ‘more trusting ethics is one of the defining elements of a network form of governance, and the network form of governance is therefore not reducible to a hybridization of market and hierarchical forms, which, in contrast, are premised on a more adversial posture’ (p. 61). In the same vein, McEvily et al. (2003) argue in their article on trust as organizing principle: ‘Organizational forms are the outcome of the workings of dominant organizing principles and, in theory, should have different characteristics depending on the underlying principle’.

Bradach and Eccles, however, state that this perspective, which, according to the authors ‘simply add[s] a category to the market and hierarchy dichotomy’ (1993, p. 277), is as misleading as the continuum view and argue instead for a shift away from ideal types (i.e. markets, bureaucracies/hierarchies and networks) to plural forms. Their major critique is that both, the continuum view and the perspective that proposes a three-fold typology are based on the flawed premise that ideal types are mutually exclusive. Certainly, Bradach and Eccles are right in pointing to the mixture of mechanisms associated with organizational forms in praxis. Stating that empirically an ideal type cannot be observed does, however, not make the concept of the network as an ideal type less useful.

Following Provan and Kenis (2008), some studies conceptualize trust as ‘structural property’ of network organizations that provides the ‘basis for collaboration’ (p. 238) in such organizations. Though these studies do not conceptualize trust explicitly as ‘control mechanism’ (Bradach and Eccles 1993), they implicitly assume coordinative effects of trust in network organizations (according to these studies, the ‘density’ of trust prevalent in a network determines the need for supplementary coordination mechanisms).

As also Grandori (1997) points out, networks (like firms and markets) employ a ‘wide range of coordination mechanisms’ (p. 32) in praxis.

See for example the longitudinal study on ‘achieving optimal trust’ in inter-organizational relationships by Stevens et al. (2015) for an interesting exception.

Schatzki (2008, pp. 83–87) also draws on the work of Foucault and Butler in his account of the constitution of individuals through practices.

Structures relating to hierarchized ends, purposes, projects etc. and/or emotions, moods.

Besides this potential, practice based theories enjoy a growing interest in organization studies and other fields (Miettinen et al. 2009) for the possibilities these theories offer for rethinking and resolving long-standing dualisms (e.g. actor/system, social/material, body/mind, theory/action) and for their exploratory and explanatory potential (Nicolini 2012).

Weiskopf and Loacker also point to competition and rivalry, and flexibility as further technologies of modulation.

It seems that this was the case for all subject positions, including subject positions that were actually quite far from this ideal like the student assistants, the ‘girls from the marketing department’ and the people working at the ‘backoffice’.

This emphasis on self-control also resonates with Baecker’s (2001) ‘indirect control’, which he constructs as a form of ‘management by ties’.

Complaining about the behavior of another Xler at a higher hierarchical level was, however, impossible. Not because there was no higher hierarchical level (as some might expect in network organizations), but because it was -again- simply not an option a competent Xler would take.

Since members of subsidiary B usually blamed their group leader for the negative aspects of their working lives, becoming a competent Xler could be sensibly constructed as a desirable goal despite the quite negative feelings members of subsidiary B had about their working lives.

Again, formal rules were avoided, because being such a ‘self-employed employee’ entails dispensing employee protection rights (which are comparatively extensive in Germany) and not contributing to or benefiting from social insurance. There may be some issues with the German Labor Law concerning this matter (Scheinselbständigkeit).

Though the company was actually founded by three persons, this founder was at times referred to as the founder.

Apart from that, increasing one’s employability is a never-ending task and company X usually always had projects. Further, and in contrast to other consultancies, there was no ‘up or out’ mentality. The network discourse allowed to imagine vertical growth instead of horizontal, hierarchical growth in which the top gets always thinner, leaving room for a few people only.

Approaching governance in network organizations from a practice-based perspective does not foreclose the possibility of trustful relationships between the members of an organization. Analytically, trust as a type of expectation or belief could for example also be approached as a ‘cognitive or intellectual life condition’ (Zustand) (Schatzki 2008, pp. 37–38) in empirical cases were trust seems more consequential than in company X.

References

Alvesson, M., & Kärreman, D. (2007). Constructing Mystery: Empirical Matters in Theory Development. The Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1265–1281.

Alvesson, M., & Willmott, H. (2002). Identity regulation as organizational control: Producing the appropriate individual. Journal of Management Studies, 39(5), 619–644.

Antivachis, N. A., & Angelis, V. A. (2015). Network organizations: The question of governance. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 175, 584–592.

Baecker, D. (2001). Managing corporations in networks. Thesis Eleven, 66(1), 80–98.

Baudry, B., & Chassagnon, V. (2012). The vertical network organization as a specific governance structure: what are the challenges for incomplete contracts theories and what are the theoretical implications for the boundaries of the (hub-) firm? Journal of Management and Governance, 16(2), 285–303.

Boltanski, L., & Chiapello, E. (2005). The new spirit of capitalism. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 18(3–4), 161–188.

Borgatti, S. P., & Cross, R. (2003). A relational view of information seeking and learning in social networks. Management Science, 49(4), 432–445.

Borgatti, S. P., & Foster, P. C. (2003). The network paradigm in organizational research: A review and typology. Journal of Management, 29(6), 991–1013.

Bradach, J. L., & Eccles, R. G. (1993). Price, authority and trust: From ideal types to plural forms. In G. Thompson, J. Frances, R. Levacic, & J. Mitchell (Eds.), Markets, hierarchies and networks: The coordination of social life (pp. 277–292). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Burt, R. S. (1997). The contingent value of social capital. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(2), 339–365.

Carpenter, M. A., Li, M., & Jiang, H. (2012). Social network research in organizational contexts: A systematic review of methodological issues and choices. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1328–1361.

Castells, M. (1996). The rise of the network society: Vol. 1: The information age: Economy, society, and culture (Vol. 1). Berkley: University of California Press.

Castells, M. (2004). The theory of the network society: Informationalism, networks, and the network society: A theoretical blueprint. In M. Castells (Ed.), The network society: A cross-cultural perspective (pp. 3–45). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405.

Collinson, D. L. (2003). Identities and insecurities: Selves at work. Organization, 10(3), 527–547.

Costa, A. C., & Bijlsma-Frankema, K. (2007). Trust and control interrelations: New perspectives on the trust control nexus. Group and Organization Management, 32(4), 392–406.

Costas, J. (2012). “We are all friends here”: Reinforcing paradoxes of normative control in a culture of friendship. Journal of Management Inquiry, 21(4), 377–395.

Cremin, C. (2010). Never employable enough: The (Im)possibility of satisfying the boss’s desire. Organization, 17(2), 131–149.

Cristofoli, D., Markovic, J., & Meneguzzo, M. (2014). Governance, management and performance in public networks: How to be successful in shared-governance networks. Journal of Management and Governance, 18(1), 77–93.

Czarniawska, B. (2004). On time, space, and action nets. Organization, 11(6), 773–791.

Czarniawska-Joerges, B. (1993). The three-dimensional organization: A constructionist view. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Davies, J. S. (2012). Network governance theory: A Gramscian critique. Environment and Planning A, 44(11), 2687–2704.

Dean, M. (2010). Governmentality: Power and rule in modern society (2nd ed.). London, Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage.

Demil, B., & Lecocq, X. (2006). Neither market nor hierarchy nor network: The emergence of bazaar governance. Organization Studies, 27(10), 1447–1466.

Dijksterhuis, M. S., van Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (1999). Where do new organizational forms come from? Management logics as a source of coevolution. Organization Science, 10(5), 569–582.

DiMaggio, P. (2001a). Conclusion: The futures of business organization and paradoxes of change. In P. DiMaggio (Ed.), The twenty-first-century firm: Changing economic organization in international perspective (pp. 210–244). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

DiMaggio, P. (2001b). Introduction: Making sense of the contemporary firm and prefiguring its future. In P. DiMaggio (Ed.), The twenty-first-century firm: Changing economic organization in international perspective (pp. 3–30). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Du Gay, P. (1996). Consumption and identity at work. London, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

Ezzamel, M., & Reed, M. (2008). Governance: A code of multiple colours. Human Relations, 61(5), 597–615.

Feldman, M. S., & Orlikowski, W. J. (2011). Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organization Science, 22(5), 1240–1253.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge. Brighton: Havester Wheatsheaf.

Gambetta, D. (1988). Can we trust trust? In D. Gambetta (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations (pp. 213–237). Oxford: Blackwell.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life (Anchor Books). New York, NY: Doubleday.

Gombault, A. (2006). Speaking organizational identity: An exploratory study of the louvre museum. In M. Kornberger & S. Gudergan (Eds.), Only connect: Neat words, networks and identities (Advances in organization studies, Vol. 20). [Lund], Abingdon: Liber; Distribution, Marston Book Services.

Grandori, A. (1997). Governance structures, coordination mechanisms and cognitive models. Journal of Management and Governance, 1(1), 29–47.

Grandori, A., & Soda, G. (1995). Inter-firm networks: Antecedents. Mechanisms and Forms. Organization Studies, 16(2), 183–214.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510.

Gulati, R. (1998). Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 19, 293–317.

Halinen, A., & Törnroos, J.-Å. (2005). Using case methods in the study of contemporary business networks. Special Section: Inter-organisational research in the Nordic countries, 58(9), 1285–1297.

Johnston, R., & Lawrence, P. R. (1993). Beyond vertical integration—The rise of the value-adding partnership. In G. Thompson, J. Frances, R. Levacic, & J. Mitchell (Eds.), Markets, hierarchies and networks: The coordination of social life (pp. 193–202). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Kilduff, M., & Brass, D. J. (2010). Organizational social network research: Core ideas and key debates. The Academy of Management Annals, 4(1), 317–357.