Abstract

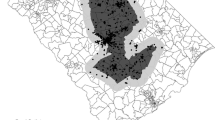

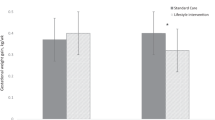

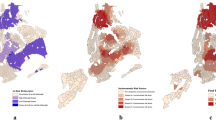

Objective To determine the risk of gestational diabetes (GDM) and preeclampsia associated with various community resources. Methods An ecological study was performed in Los Angeles and Orange counties in California. Fast food restaurants, supermarkets, grocery stores, gyms, health clubs and green space were identified using Google © Maps Extractor and through the Southern California Association of Government. California Birth Certificate data was used to identify cases of GDM and preeclampsia. Unadjusted and adjusted risk ratios were calculated using negative binomial regression. Results There were 9692 cases of GDM and 6288 cases of preeclampsia corresponding to incidences of 2.5 and 1.4 % respectively. The adjusted risk of GDM was reduced in zip codes with greater concentration of grocery stores [relative risk (RR) 0.95, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.92–0.99] and supermarkets (RR 0.94, 95 % CI 0.90–0.98). There were no significant relationships between preeclampsia and the concentration of fast food restaurants, grocery store, supermarkets or the amount of green space. Conclusion The distribution of community resources has a significant association with the risk of developing GDM but not preeclampsia.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hartling, L., et al. (2012). Screening and diagnosing gestational diabetes mellitus. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (Full Report), 210, 1–327.

Moyer, V. A., & U.S.P.S.T. Force. (2014). Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 160(6), 414–420.

Gynecologists A.C.o.O.a. (2013). Practice Bulletin No. 137: Gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 122(2 Pt 1), 406–416.

Walker, J. J. (2000). Pre-eclampsia. Lancet, 356(9237), 1260–1265.

Lisonkova, S., & Joseph, K. S. (2013). Incidence of preeclampsia: Risk factors and outcomes associated with early- versus late-onset disease. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 209(6), 544e1–544e12.

Ananth, C. V., Keyes, K. M., & Wapner, R. J. (2013). Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980–2010: Age–period–cohort analysis. BMJ, 347, f6564.

Duckitt, K., & Harrington, D. (2005). Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: Systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ, 330(7491), 565.

Eiriksdottir, V. H., et al. (2015). Pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders before and after a national economic collapse: A population based cohort study. PLoS ONE, 10(9), e0138534.

Solomon, C. G., et al. (1997). A prospective study of pregravid determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA, 278(13), 1078–1083.

James, P. A., et al. (2014). 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA, 311(5), 507–520.

Janevic, T., et al. (2010). Neighbourhood food environment and gestational diabetes in New York City. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 24(3), 249–254.

Vinikoor-Imler, L. C., et al. (2011). Neighborhood conditions are associated with maternal health behaviors and pregnancy outcomes. Social Science and Medicine, 73(9), 1302–1311.

Laurent, O., et al. (2013). Green spaces and pregnancy outcomes in Southern California. Health Place, 24, 190–195.

Lhila, A. (2011). Does access to fast food lead to super-sized pregnant women and whopper babies? Economics & Human Biology, 9(4), 364–380.

Fowles, E. R., et al. (2011). Eating at fast-food restaurants and dietary quality in low-income pregnant women. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 33(5), 630–651.

Messer, L. C., Vinikoor-Imler, L. C., & Laraia, B. A. (2012). Conceptualizing neighborhood space: Consistency and variation of associations for neighborhood factors and pregnancy health across multiple neighborhood units. Health Place, 18(4), 805–813.

Hutchinson, P. L., et al. (2012). Neighbourhood food environments and obesity in southeast Louisiana. Health Place, 18(4), 854–860.

Morland, K., Diez Roux, A. V., & Wing, S. (2006). Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(4), 333–339.

Mobley, L. R., et al. (2006). Environment, obesity, and cardiovascular disease risk in low-income women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(4), 327–332.

Richardson, A. S., et al. (2012). Are neighbourhood food resources distributed inequitably by income and race in the USA? Epidemiological findings across the urban spectrum. BMJ Open, 2(2), e000698.

Cheadle, A., et al. (1991). Community-level comparisons between the grocery store environment and individual dietary practices. Preventive Medicine, 20(2), 250–261.

Clarke, P., et al. (2010). Using Google Earth to conduct a neighborhood audit: reliability of a virtual audit instrument. Health Place, 16(6), 1224–1229.

Lefer, T. B., et al. (2008). Using Google Earth as an innovative tool for community mapping. Public Health Reports, 123(4), 474–480.

Acknowledgments

The source of the work is from the California Birth Certificate Database, Google Maps Extractor Software, Southern California Association of Government, Census 2010 and the American Community Survey. Funding was provided by Health Effect Institute (HEI 4787-RFA09-4110-3 WU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Young, C., Laurent, O., Chung, J.H. et al. Geographic Distribution of Healthy Resources and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Matern Child Health J 20, 1673–1679 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-1966-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-1966-4