Abstract

Preterm birth (PTB) is a leading cause of newborn deaths and morbidities. The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS) from the U.S., and the maternity experiences survey (MES) from Canada, which was modeled from PRAMS, were used to examine between-country differences in risk factors of preterm birth. The adjusted risk ratio and population attributable fraction (PAF) were calculated for modifiable and semi-modifiable risk factors of PTB, and all measures were compared between the U.S. and Canada. PTB was defined here as a live singleton birth between 28 and 37 completed weeks gestation (using the clinical gestational age estimate) where the baby was living with the mother at the time of the survey. The PTB risk was 7.6 % (SE = 0.2) in the U.S. and 4.9 % (SE = 0.3) in Canada. The a priori high risk category of factors was almost always more prevalent in the U.S. than Canada, suggesting broad social differences, but individually most of these differences were not associated with PTB. The underlying risk of PTB was generally higher in the U.S. in both the higher risk and referent categories, and the risk ratios for most risk factors were similar between the countries. The primary exception was for recurrence of PTB, where the risk ratio (RR) and PAF were much higher in Canada. We observed between-country differences in both the prevalence of risk factors and the adjusted RR. Further between-country comparisons may lead to important inferences as to the influence of modifiable risk factors contributing to PTB.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Callaghan, W. M., MacDorman, M. F., Rasmussen, S. A., Quin, C., & Lackritz, E. M. (2006). The contribution of preterm birth to infant mortality rates in the United States. Pediatrics, 118(4), 1566–1573. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0860.

Saigal, S., & Doyle, L. W. (2008). An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet, 371(9608), 261–269. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60136-1.

Kinney, M. V., Lawn, J. E., Howson, C. P., & Belizan, J. (2012). 15 million preterm births annually: What has changed this year? Reproductive Health, 9, 28. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-9-28.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2012). Perinatal health indicators for Canada 2011. Ottawa.

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Ventura, S. J., Osterman, M. J., Wilson, E. C., & Matthews, T. J. (2010). Births: Final data for. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2012, 1–72.

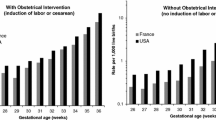

Joseph, K. S., Huang, L., Liu, S., Ananth, C. V., Allen, A. C., Sauve, R., et al. (2007). Reconciling the high rates of preterm and postterm birth in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 109(4), 813–822. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000255661.13792.c1.

Beck, S., Wojdyla, D., Say, L., Betran, A. P., Merialdi, M., Requejo, J. H., et al. (2010). The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: A systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88(1), 31–38. doi:10.2471/BLT.08.062554.

VanderWeele, T. J., Lantos, J. D., & Lauderdale, D. S. (2012). Rising preterm birth rates, 1989–2004: Changing demographics or changing obstetric practice? Social Science and Medicine, 74(2), 196–201. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.031.

Joseph, K. S., Kramer, M. S., Marcoux, S., Ohlsson, A., Wen, S. W., Allen, A., et al. (1998). Determinants of preterm birth rates in Canada from 1981 through 1983 and from 1992 through 1994. New England Journal of Medicine, 339(20), 1434–1439. doi:10.1056/NEJM199811123392004.

Rossignol, M., Moutquin, J. M., Boughrassa, F., Bedard, M. J., Chaillet, N., Charest, C., et al. (2013). Preventable obstetrical interventions: How many caesarean sections can be prevented in Canada? Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 35(5), 434–443.

Lawn, J. E., Gravett, M. G., Nunes, T. M., Rubens, C. E., & Stanton, C. (2010). Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (1 of 7): Definitions, description of the burden and opportunities to improve data. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 10(Suppl 1), S1. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S1.

Dzakpasu, S., Kaczorowski, J., Chalmers, B., Heaman, M., Duggan, J., & Neusy, E. (2008). The Canadian maternity experiences survey: Design and methods. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 30(3), 207–216.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2009). What mothers say: The Canadian maternity experiences survey. Ottawa.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). PRAMS model surveillance protocol, 2009 CATI version.

Shulman, H. B., Gilbert, B. C., & Lansky, A. (2006). The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS): Current methods and evaluation of 2001 response rates. Public Health Reports, 121(1), 74–83.

Tita, A. T. N., Landon, M. B., Spong, C. Y., et al. (2009). Timing of elective repeat Cesarean delivery at term and neonatal outcomes. The New England Journal of Medicine, 360, 111–120.

Rockhill, B., Newman, B., & Weinberg, C. (1998). Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. American Journal of Public Health, 88(1), 15–19.

Adams, M. M., Elam-Evans, L. D., Wilson, H. G., & Gilbertz, D. A. (2000). Rates of and factors associated with recurrence of preterm delivery. JAMA, 283(12), 1591–1596.

Ananth, C. V., & Vintzileos, A. M. (2006). Epidemiology of preterm birth and its clinical subtypes. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 19(12), 773–782. doi:10.1080/14767050600965882.

Mazaki-Tovi, S., Romero, R., Kusanovic, J. P., Erez, O., Pineles, B. L., Gotsch, F., et al. (2007). Recurrent preterm birth. Seminars in Perinatology, 31(3), 142–158. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2007.04.001.

Mercer, B. M., Goldenberg, R. L., Moawad, A. H., Meis, P. J., Iams, J. D., Das, A. F., et al. (1999). The preterm prediction study: Effect of gestational age and cause of preterm birth on subsequent obstetric outcome National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 181(5 Pt 1), 1216–1221.

Goldenberg, R. L., & Rouse, D. J. (1998). Prevention of premature birth. New England Journal of Medicine, 339(5), 313–320. doi:10.1056/NEJM199807303390506.

Galtier-Dereure, F., Boegner, C., & Bringer, J. (2000). Obesity and pregnancy: Complications and cost. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 71(5 Suppl), 1242S–1248S.

Kingston, D., Heaman, M., Fell, D., Dzakpasu, S., & Chalmers, B. (2012). Factors associated with perceived stress and stressful life events in pregnant women: Findings from the Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16(1), 158–168. doi:10.1007/s10995-010-0732-2.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the guidance of The PREterm Birth International Collaborative (PREBIC) Epidemiology workgroup for facilitating the relationship between the U.S. and Canadian collaborators. PREBIC is a nonprofit organization, supported by the WHO and the March of Dimes (www.prebic.net). We are also grateful to the PRAMS working group (http://www.cdc.gov/prams/PDF/WorkingGroup_7-2012.pdf ), and to the staff at the Prairie Regional Data Centre for the approval of this project and for making the data available for this project. J.V.G. is supported in part by a NIH training grant in reproductive, perinatal and pediatric epidemiology through Emory University (T32HD052460). A.M. is funded by a fellowship award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. S.T. is funded by a health scholar award from Alberta Innovates—Health Solutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garn, J.V., Nagulesapillai, T., Metcalfe, A. et al. International Comparison of Common Risk Factors of Preterm Birth Between the U.S. and Canada, Using PRAMS and MES (2005–2006). Matern Child Health J 19, 811–818 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1576-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1576-y