Abstract

Recent advances in the Super Linguistics of pictures have laid the Super Semantic foundation for modelling the phenomena of narrative sequencing and co-reference in pictorial and mixed linguistic-pictorial discourses. We take up the question of how one arrives at the pragmatic interpretations of such discourses. In particular, we offer an analysis of: (i) the discourse composition problem: how to represent the joint meaning of a multi-picture discourse, (ii) observed differences in narrative sequencing in prima facie equivalent linguistic vs pictorial discourses, and (iii) the phenomenon of co-referencing across pictures. We extend Segmented Discourse Representation Theory to spell out a formal Super Pragmatics that applies to linguistic, pictorial and mixed discourses, while respecting the particular ‘genius’ of either medium and computing their distinctive pragmatic interpretations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

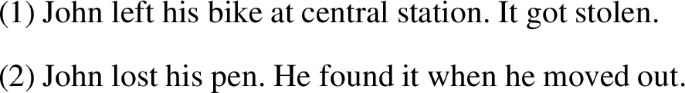

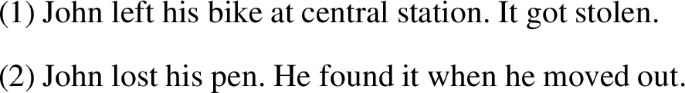

The interpretation of a discourse often goes beyond the meanings of its constituent sentences. For example, (1) below is understood as a narrative in which Tweetie fell because Dino pushed her. This causal information is not contributed by one of the individual sentences. Rather, it arises from interpreting the sentences jointly as a discourse.

The same phenomenon can be observed for pictorial discourses. For example, Abusch (2014) discusses (2), adapted from Masashi Tanaka’s silent manga Gon, which is a pictorial analogue of (1).

Building on the seminal work by Abusch (2013, 2014, 2020), we recently argued that pragmatic principles in Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT, Asher and Lascarides, 2003), originally conceived to predict the correct interpretation of linguistic narratives like (1), can be adjusted to deliver the right predictions for narrative sequencing in pictorial discourses (Altshuler & Schlöder, 2021). Underlying this analysis is the assumption that pictures can be assigned semantic contents that are suitable for SDRT logical forms. But this assumption is not a trivial matter, giving rise to what we will call the discourse composition problem:

For the pieces of information contained in linguistic discourses like (1), we can address (3) via composition principles that are phrased in the language of event semantics. That is, by associating each sentence with a main eventuality and letting the discursive meaning postulates specify relations between eventualities (Asher and Lascarides, 2003). But pictures do not denote, in any obvious sense, a main eventuality (Abusch, 2014). Hence, it’s not clear how to address (3) with respect to pictorial narratives. Whatever one’s solution to the discourse composition problems for linguistic and pictorial narratives, it better be generalizable to a common formal language, since mixed discourses are interpretable in the same way that ‘pure’ linguistic and ‘pure’ pictorial discourses are interpretable.

We must be able to compose linguistically given information with pictorially given information. But it is not at all clear what kinds of information are composed in the interpretation of (4). What is clear, however, is that (4) is interpreted the same as the two ‘pure’ examples in (1) and (2): Dino kicking Tweety caused her to fall.

Note that, as currently phrased, (3) is not about what the meaning postulates are. Rather, (3) is about the question on what kinds of content these postulates should operate and, concomitantly, in what formal language one should phrase the postulates. Whatever one’s solution to (3), it must satisfy the following constraint:

To appreciate the role of this constraint, first consider the linguistic discourse below, where (6a) causes (6c), and (6b) is offered as background information with no particular relevance to this causal relation.

Now compare (6) to (7):

Here, we infer that (7a) and (7b) jointly cause (7c). The content of (7a) alone is not what causes John to slip and fall. Rather, what causes this is the fact that (7a) and (7b) were simultaneously the case. In other words, (7a) and (7b) co-occur and this co-occurrence causes (7c). Note that it is not merely the conjunction of (7a) and (7b) that is the cause of (7c). The fact that the states described in (7a) and (7b) occur in spatio-temporal overlap is not part of the content of either sentence and hence not part of their conjunction, but only part of their composition. This overlap is pivotal for the interpretation of (7a) and (7b) as the cause of (7c).

It is, therefore, incumbent on a theory of narrative semantics to assign a meaning to the composition of (7a) and (7b) that contains the interpretation of their contents as describing overlapping states. Moreover, their composition must be such that it can, then, be composed with further linguistically given contents like (7c). That is, the meaning postulates for the composition of narratives operate equally on sentence meanings and on narrative meanings. Thus, the composition of (7a) and (7b), i.e. a narrative meaning, must be of the same type of content as the meaning of a sentence.

When we combine the insight from (3) and (5), we can rephrase the discourse composition problem as follows:

To see how (8) manifests in pictorial discourse, consider the following variant of (7):

The interpretation of (9) is the same as (7). That is, (9a) does not by itself cause (9c), but it is the fact that (9a) and (9b) co-occur—that is, the narrative arising from the composition of (9a) and (9b)—that causes (9c).Footnote 1 But what is their composition? Again, one important constraint is that the meaning of the composition of two pictures can then be composed further with another picture. Thus, regardless of the medium, a solution to (8) must have the following property:

SDRT shows how (10) is respected for linguistic discourse, but no one (to the best of our knowledge) has shown this for pictorial discourse. Worse, there are mixed media discourses like (11):

The interpretation is the same as before, but now the cause of (11c) is a composition of linguistic information and a picture. We must answer the question of what this composition even is (in what language it could be stated) and how it can compose further with linguistically or pictorially given information. Given (8) and (10), the interpretation of (4) and (11) must be derived by meaning postulates that compose meanings that can encompass both linguistically and pictorially given information. Rooth and Abusch (2019) have made important strides in solving the problem of combining linguistic and pictorial information; in particular, they have proposed an account of cross-medium anaphora. What is not provided, however, is a worked out account of discourse composition that is adequate to explain examples like (11). The challenge is to phrase narrative meaning postulates that explain how the composition of (11a) and (11b) can further compose with (11c) to vindicate the intuitive causal meaning, also resolving the anaphora in (11c).

The pictorial sequence below, in (12), gives rise to another analytical challenge that does not apply to its linguistic counterpart in (7). To appreciate this challenge, note that anaphora resolution is necessary to derive the causal reading in (7), i.e. he in (7c) is understood to pick out John. But what about in (9)? As first observed by Abusch (2013), there is no obvious analogue to anaphora in pictures. Note that it is not necessary to interpret the two stick figures in (9a) and (9c) to be co-referential. The sequence (9) could be continued as in (12) with a depiction of the figure with the phone helping up the figure that slipped, cementing the non-co-referential reading.

This is not possible in (7) as shown in (13).

As argued by Maier and Bimpikou’s (2019), co-reference in pictures is purely pragmatic, as opposed to the partially syntactic, and more constrained, process of resolving anaphora and other linguistic means to establish co-reference. Nevertheless, there are reasons to believe that tools from linguistic theorizing can be brought to bear here. Rooth and Abusch (2019) propose an analysis of pictures in which any depiction of a referent can act as a binder. They motivate this idea with mixed media discourses, using linguistic anaphora as a test. In (11c) the anaphor he refers to the stick figure in (11a), indicating that the depiction is a binder. However, it would be too hasty to conclude that pictorial co-referencing is established by a familiar kind of pragmatics to establish co-reference between indefinites. If depictions are binders that are broadly akin to indefinites, the content of (9) roughly corresponds to the following discourse.

Compared to the interpretation of (9), it is substantially more difficult (and less natural) to interpret (14) so that the man from (14a) and (14c) are the same.

By probing such analogies and disanalogies, we can get a clearer picture of how co-reference in pictorial narratives functions. First, consider the Partee sequence in (15).Footnote 2 Such examples demonstrate that anaphoric reference does not involve contextually entailed antecedents, but rather require explicit binders, as in (16).

In contrast, referencing by description does not have this requirement, as seen in (17).Footnote 3

Now, the following is (arguably) a pictorial analogue of referring to contextually entailed referents.

This is felicitous and the natural interpretation of this example is that the bishop in the second picture is the very bishop missing from the first picture. So, in an obvious (but perhaps inexact) sense, the interpretation of (18) involves co-reference. But not co-reference between two depicted referents, but rather between a depiction and something saliently absent from another picture. The absence of something is however not a binder, as seen in (19):

If the absence of the bishop in the picture were a binder, we would be able to bind the anaphor it to the missing bishop, but apparently we cannot. The only possible interpretation of the anaphor it is that the whole chessboard is under the couch. However, the visible background in the first picture appears to rule that out too.

The interpretation of (18) is that the chess set depicted in the first picture is incomplete and that the bishop depicted in the second picture is the missing piece. In this paper, we will develop an analysis in which both pictures make reference to the same, not depicted complete set. The existence of a completed set arises from interpreting the pictures in (18) as a coherent narrative. An important consequence of this analysis is that there is no immediate analogue between reference in pictorial and linguistic narrative in spite of our ability to refer across media. This is a puzzle for the study of reference in pictorial narratives.

One may object to this analysis by saying that co-reference across pictures is (loosely) akin to reference by description in linguistic narratives.Footnote 4 This hypothesis is prima facie supported by comparing (18) with (17). Applying the hypothesis to (18) and (19), we would say that the infelicity of (19) suggests that the bishop in the second picture of (18) refers to an entity without an explicit binder. While this analysis appears plausible for the examples just considered, there are some cases where it fails, namely in some longer narrative sequences where there is clear difference between linguistic reference by description and pictorial co-referencing.

Unlike anaphora, descriptions can refer across narrative segments that (in an intuitive sense made precise in Sect. 3) advance the narrative. First compare the following two examples of linguistic co-referencing.

The sentence Later he went dancing in (20) advances the narrative from John’s meal. Consequently, one can reference the burger only by description, but not anaphorically. While it may be possible, with some effort, to understand what the speaker of (20) is trying to convey, namely that the energy drink is what gave John energy for dancing, there is a strong sense that this is not a good way to convey this. There is no such sense when the burger is referred to descriptively, as in (21).

Now, when we consider pictorial versions of such examples, as in (22), we find that co-reference in pictures does not share this property of descriptive reference. That is, an intervening, narrative-advancing picture blocks pictorial co-reference.

Without such an intervening picture, as in (23), reference to the burger is however possible.Footnote 5

In sum, there are empirical differences between linguistic and pictorial narratives with respect to co-reference. The challenge is to explicate pragmatic principles that: (i) apply uniformly to both linguistic and pictorial narratives and (ii) explain how co-reference works in either medium and when we mix media. The aim of this paper is to develop a Super Pragmatics that achieves these goals, while also solving the discourse composition problem. We show how our proposal serves as a vital complement to the growing Super Semantics research on pictorial narratives.Footnote 6

The paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we overview PicDRT, a formal framework introduced by Maier and Bimpikou’s (2019) to deal with point of view in pictorial narrative, synthesizing Discourse Representation Theory (Kamp, 1981; Geurts, 1999) with possible world semantics for pictures (Greenberg, 2011; Abusch, 2013). While we will not have anything new to say about point of view, PicDRT will allow us to clarify a formal notion of picture content and the desiderata for having an adequate pragmatic account of co-reference in pictures and language. In Sect. 3, we review some relevant components of Segmented Discourse Representation Theory, with particular attention to the discourse composition problem, narrative sequencing and co-reference. This will set the stage for our novel contribution in Sect. 4, where we extend PicDRT to incorporate insights from SDRT and offer a Super Pragmatic proposal for how to compose pictorial and mixed discourses to obtain pragmatic interpretations that make the right prediction for co-reference within and across media. We conclude the paper in Sect. 5, summarizing our contribution and prospects for further research.

2 Motivating super pragmatics

2.1 Super semantics of pictures

2.1.1 T-schema for pictures

Greenberg (2011) and Abusch (2013) have shown that the notion of truth in a world—commonly used in possible world semantics of linguistic expressions—is helpful in thinking about the meaning of pictures. This is so, despite pictures not having a compositional structure—at least not obviously so. The T(ruth)-schema for pictures draws on the notion resemblance:

To appreciate (24), we must unpack what is meant by resemblance. For Abusch and Greenberg, this notion correlates to a projection function from a three-dimensional scene to two-dimensional plane; see Fig. 1. More precisely, a projection function \(\pi \) takes a world w and a viewpoint v and returns a picture p.Footnote 7 Hence, we could re-write the T-scheme above as in (25) below. In turn, propositional content of a picture can be defined as the set of worlds in which the picture is true from some viewpoint.

Scenes and viewpoints. Graphic from Greenberg (2013)

In the next section, we briefly outline Maier and Bimpikou’s (2019) proposal to build on the analysis above and model the dynamics of multipanel visual story-telling.Footnote 8

2.1.2 Co-reference: from DRT to PicDRT

Maier and Bimpikou’s (2019) introduce their framework, PicDRT, by first considering a DRT analysis of the linguistic discourse below, from Geurts (1999):

Applying a DRT construction algorithm to the first sentence in (27) results in the discourse representation structure (DRS) below, which adopts the standard box notation. (For simplicity, we ignore some parts of the linguistic content, including tense and gender marking.)

The so-called universe of the DRS includes the discourse referents (drefs) \(x_1\) and \(y_1\), which can be thought of as existentially quantified variables of first-order predicate logic. In DRT, they stand for the entities that the discourse is about. Below the universe, there is a set of conditions which express properties of, and relations between, the drefs. The truth conditions for the DRS in (28) are as follows: the DRS in (28) is true iff there is an assignment function (so-called embedding in DRT) that maps the drefs \(x_1\) and \(y_1\) to individuals in the domain of the model such that \(x_1\) is a policeman, \(y_1\) is a squirrel and \(x_1\) chased \(y_1\).

As shown below, in (29), the second sentence is interpreted in the context of the DRS in (28). Here, the pronouns are left unresolved. This is commonly represented with a condition that relates a dref introduced by a pronoun to a question mark, e.g, \(x_1 = ?\), which stands for the information that \(x_1\) needs to be resolved to some (accessible) dref in the universe of the DRS.

DRT does not provide an algorithm for how the resolution comes about. However this is not its aim. Its aim is to provide the semantic underpinnings—a point that we come back to below. Assuming some pragmatic algorithm for the resolution of underspecified conditions of the form \(x=?\), we arrive at the DRS below, which captures the intuitive truth conditions of the discourse.

The discourse could then continue with further information about the policeman or the squirrel using pronouns or other definites, or it could introduce new characters in the story by using indefinites.

Let us now consider a pictorial version of the discourse provided by Maier and Bimpikou (2019, 94):

To model the interpretation of this pictorial narrative, Maier and Bimpikou’s extend the DRS language with picture conditions, i.e. with the language of PicDRS. These conditions consist of a picture discourse referent \(p_i\), along with the actual picture. Moreover, following the insight of Abusch (2013) and Rooth and Abusch (2019), Maier and Bimpikou’s impose structure on pictures to identify drefs in the pictures. In particular, they assume that the PicDRS construction algorithm “manages to identify some regions of interest in a picture, viz. those regions that correspond to salient entities ... and label those regions with fresh discourse referents” (Maier and Bimpikou, 2019, 94). Given this assumption, Maier and Bimpikou’s represent the the first picture in the story as in (97), paraphrasing this PicDRS as: ‘there is a situation in the world that (from some viewpoint) looks like the picture, and in that situation there are two salient individuals, who look like the two regions labeled in the picture.’

So far so good. But now a difficult question arises: how should we model co-reference in (31)? As noted by Abusch (2013), since there are no pictorial analogues of pronouns (or any other co-reference markers)—at least not obviously so—it is unclear what mechanisms (if any) specify that a given object is the same across pictures. Put differently, there do not appear to be any constraints that prevent the viewer from representing two new objects in the second picture of (31) and saying that they look similar to the objects represented in the first picture. In light of this observation, Maier and Bimpikou (2019, 95) follow Abusch and assume that each picture in a sequence introduces new drefs (corresponding to salient regions):

Moreover, Maier and Bimpikou’s assume that “it is left to pragmatics to determine whether some [dref] are to be treated as coreferential” (Maier and Bimpikou, 2019, 95). Hence, as with the analysis of the linguistic discourse in DRT, the analysis of pictorial narrative in PicDRT assumes that there is some pragmatic algorithm that will deliver the correct results. Once that assumption is made, the pragmatically strengthened representation below emerges:

Maier and Bimpikou’s provide the following paraphrase, which is in accordance with our intuitions: ‘there’s a situation that looks like the first picture, with two agents, looking like the two labeled regions, and there is another situation that looks like the second picture, with these same two agents, now looking like the two labeled regions in the second picture.’

It is important to note that this paraphrase is quite similar to the one given for the linguistic discourse. This is a good result since we take the pictorial narrative to be an adequate translation of the linguistic narrative. Crucially, however, the derivations that lead to the two paraphrases are quite different. Abusch (2013) argues that in the linguistic case, co-reference is, in part, encoded in the linguistic structures (e.g. by way of pronouns), but in pictures, co-reference is purely pragmatic. An interpreter may or may not interpret the policeman in the second picture to be co-referential with the policeman in the first picture, whereas the interpretation of a pronoun in a linguistic discourse is more constrained (also see Maier and Bimpikou, 2019, 95). That is, in the linguistic case the DRT construction algorithm explicitly introduced conditions like \(x_2 = ?\) and \(y_2 = ?\) that prompt a pragmatic algorithm to find binders for \(x_2\) and \(y_2\), but for establishing co-reference across pictures, the algorithm must make do without this. Moreover, this algorithm must be different from the one we use to establish co-reference in linguistic discourse in the absence of explicit co-referential structure. As previewed in Sect. 1, sequences of indefinites are harder to read as co-referential as sequences of pictures. The following is less naturally read as being about a single policeman and squirrel than (31).

In Sect. 4, our goal will be to explicate how it is that an interpreter establishes identity between objects depicted in pictures. Luckily, there is some precedence. As previewed in Sect. 1, SDRT offers the necessary tools to analyze co-reference in natural language discourse. In Sect. 3, we will provide an overview of the tools that we will then extend to the pictorial domain. Before doing so, however, it will be worthwhile to consider narrative sequencing in pictorial narratives. This will allow us to introduce some further empirical generalizations, as well as further theoretical assumptions that will buttress our ultimate analysis.

2.2 Narrative sequencing

2.2.1 A Dowty-style super pragmatics

Consider the pair of pictorial narratives below, in (36) and (37), discussed by Abusch (2014). They illustrate that regardless of the order in which two pictures are presented, the cause-effect interpretation remains constant: Tweetie was pushed by Dino and, as result, she fell down the cliff.

Now consider the sequence of pictures in (38), taken from McCloud (1994) and discussed by Abusch , where it is possible to infer that an individual was wearing glasses while the sun was out. That is, it is possible to infer that the situations depicted in the two pictures temporally overlap.Footnote 9

Thus, all three possible temporal orderings (succession, regression, overlap) occur in the interpretation of pictorial discourses. Nevertheless, Abusch (2014) suggests that by default, we read pictures as depicting thing in successive temporal order. This assumption is also adopted by Maier and Bimpikou’s (2019): “a picture to the right or below (in Western comics and picture books) another corresponds to a state of affair that comes later. We model this by adding a DRS condition of the form \(p_1 < p_2\).” This idea is illustrated by the DRS of the now familiar police/squirrel discourse below, where the noted DRS condition has been added:

For Maier and Bimpikou’s , this additional temporal condition is a case of pragmatic strengthening, just like the other conditions (in which the drefs are equated). And, once again, it will be our goal in Sect. 4 to explicate how it is that the interpreter establishes particular temporal relationships between pictures (in addition to identity relationships between objects depicted in pictures). In this section, we consider the only Super Pragmatic proposal that we know of, proposed by Abusch (2014, 2020), which attempts to address this question.

Key to Abusch’s proposal is the hypothesis below:

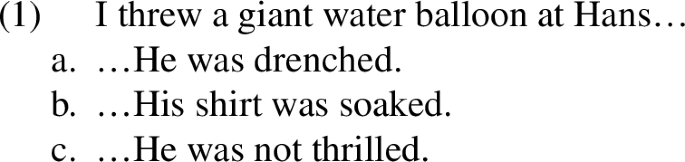

At first blush, (40) may seem wrong. After all, there are many pictures which we would linguistically paraphrase using an event description. Indeed, artists often use conventions like ‘movement lines’ to indicate a change-of-state, as in (41) below, which may be paraphrased as ‘Some dude in a light blue shirt threw a water balloon.’

In what sense, then, is this is a stative depiction of the world? According to Abusch , whatever change-of-state inferences are made by the viewer, those inferences are pragmatic. For example, in the picture above, we infer that the water-balloon moved from point x to point y. However, according to Abusch , the picture doesn’t semantically depict this. Abusch (2020, 11) makes the analogy to the linguistic sentence below, which presumably describes a moving comet and yet the proposition that the sentences denotes is linguistically stative.

Abusch ’s main evidence for the hypothesis in (40) comes from showing that pictures have the subinterval property, which is characteristic of statives (Bennett and Partee, 2004). She considers the model theoretic interpretation of the picture below,

and reasons as follows:

Suppose that in world w there is a scene with a black and a white cube that projects to the picture with respect to viewpoint v at time point t. If the cubes are static in an interval i that contains t, then the scene projects to the same picture with respect to v at any time point \(t'\) in i. So the proposition [denoted by (43)] is true of w, \(t'\) for every point \(t'\) in the interval i. And if one extends the truth definition to include truth with respect to intervals, then the proposition is true with respect to every subinterval of i. This pattern of truth is characteristic of stative propositions. (Abusch, 2020, 11)

But if (40) is correct, there is a puzzle. Many theories of narrative progression link it to eventive descriptions (e.g. Kamp and Rohrer, 1983; Lascarides and Asher, 1993). Here, narrative progression is realized by stative depictions, so we have a choice:Footnote 10

-

Say that aspect interacts differently with narrative progression depending on the medium.

-

Throw out the idea that aspect is relevant to narrative progression (and then do everything with common sense reasoning).

Abusch chooses the latter option, as it would be unsatisfying to have different pragmatic theories apply in different media. (We concur, the data on mixed media narratives alone seems to render this a non-starter.) To provide a uniform pragmatic analysis of narrative sequencing across media, Abusch adopts a version of Dowty’s (1986) influential analysis of narrative progression and extends it to pictorial discourse. The key idea is this. Like linguistic narratives, pictorial narratives are subject to fixed rules that force pictures to be understood in succession and common sense pragmatics can “extend” a state in time to infer temporal overlap.

Applying this analysis to (36) and (37) is straightforward, where we already observe eventuality sequencing. Causal reasoning does the rest: it determines the nature of the sequence, i.e., narrative progression vs narrative regression. Moreover, the overlapping interpretation in (38) is also expected to be possible. We can make the natural assumption that the sun was out before the individual wore glasses. Hence we have sequencing, which is compatible with the sun continuing to be out while the individual wore glasses. Assuming this interpretation is the most plausible one (given common sense reasoning), this is what is inferred. Note that although this overlapping interpretation is what one likely obtains when confronted with (38), other interpretations are (in principle) compatible with the information presented in (38), e.g. that the sun set before the individual put on glasses. The possibility to assign such interpretations as well appears to underwrite the role of common sense when interpreting (38).

Dowty’s analysis was originally motivated by narrative progression in linguistic narratives. The examples in (44), (45) and (46) illustrate temporal succession, temporal precedence and temporal overlap respectively.

Here we can infer by common sense reasoning that throwing a water balloon precedes Hans’s shirt getting wet; cooking is presented as an excuse for being late, and thus precedes the lateness; and that the sun being out temporally overlaps one putting on their sunglasses.

The parallel between these linguistic data (on the one hand) and the pictorial data above (on the other hand) led Abusch to conclude that narrative progression rules are the same across media, even if one medium lacks event descriptions. This entails that Abusch, like Dowty, denies the Aspect Hypothesis defended by Kamp and Rohrer (1983).

In the next section, we see examples of linguistic narrative that suggest reviving (some version of) this hypothesis. This prompts us to rethink Abusch’s Super Pragmatic approach.

2.2.2 Reviving the aspect hypothesis

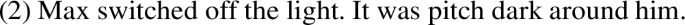

Altshuler (2021) provides the linguistic narrative in (48) to show that some event-state sequences (ESSs) cannot have a causal interpretation, despite what common sense pragmatics tells us. To the extent that this sequence could be interpreted, it could only mean that the speaker threw a water balloon at Hans when his shirt is already wet.Footnote 11

Such data suggests that the Aspect Hypothesis is operative here. To be convinced, compare (48) with (44) from the previous section. Based on common sense alone, both examples should lead us to infer a causal relation and in particular that the throwing of the water balloon precedes the wetness of the shirt. But while this is the natural interpretation of (44), this is not so for (48). When reading (48), one prefers an overlapping interpretation: that the shirt was already wet. The only salient difference between (48) and (44) is the aspect of the second sentence.

In light of this contrast, note that the overlapping interpretation is not possible in (49). The causal interpretation is the only one available, just like common sense pragmatics tells us.

Based on these data, we concluded in earlier work that there is a difference in the interpretation of linguistic and pictorial narratives (Altshuler and Schlöder, 2021). We observed that as far as common sense is concerned, the linguistic narrative (48) and the pictorial narrative (49) appear to confront us with the same information, yet we seem to interpret them differently. This puts pressure on the Dowty-style Super Pragmatics of narrative progression.

The following example, which we first discussed in Altshuler and Schlöder (2021), provides further evidence for such a conclusion with an even more striking contrast in (50) and (51).

The Aspect Hypothesis predicts that we should infer in (50) that the mouse being dead overlaps the event of it being bitten while wiggling its tail. But then there is no pragmatic context that could make this ESS felicitous because in any such context it would (absurdly) be the case that the mouse wiggles its tail while dead. That is, the Aspect Hypothesis makes the correct prediction for (50). But this is not what is predicted by common sense reasoning: that the mouse died because a cat bit into it (i.e. a causal interpretation on which the being-dead succeeds the biting). Unlike in the linguistic discourse (50), the causal interpretation is available (and indeed the only available one, lest the mouse be in two positions at the same time) in the pictorial narrative in (51).

These contrasts motivate a Super Pragmatic puzzle. As we put it in Altshuler and Schlöder (2021):

If Abusch’s Dowty-style analysis of pictorial narratives is correct and the examples in [(48) and (50)] do vindicate the Aspect Hypothesis for linguistic narratives, then different principles govern narrative sequencing in these media. This, however, would be unsatisfying. We know of no reason why our assessment of basically the same pieces of information should fundamentally vary with whether that information is presented linguistically or pictorially. But then how can it be that linguistic and visual narrative differ with respect to the availability of causal inferences?

We can also put the puzzle as follows. There seems to be a principle operative in the interpretation of pictorial discourse that leads us to, by default, interpret a sequence of pictures as depicting eventualities in succession. We have seen that there are exceptions to this principle that are in need of explanation. Our goal will be to give a more general, formal description of the process of interpreting pictures that explains both why usually pictures are read in succession and why sometimes this is not so.

In the next section, we show how a formal Super Pragmatic analysis can make the correct predictions if we adopt both Abusch’s Hypothesis in (40) and the Aspect Hypothesis in (47). This will allow us to exploit aspectual differences between linguistic and pictorial narrative to provide a single pragmatic algorithm. This algorithm will employ the formal tools of SDRT, which we outline in turn. Then, in Sect. 4, we extend these tools to offer a Super Pragmatics of co-reference in pictorial discourse and a solution to the discourse composition problem noted in Sect. 1.

3 The fundamentals of segmented DRT

SDRT is a formal theory of how one pragmatically enriches a discourse with coherence relations and how this leads to the pragmatic interpretation of a discourse (Lascarides and Asher, 1993; Asher and Lascarides, 1998, 2003; Asher and Vieu, 2005). The guiding idea is that discourses (consisting of clauses or, here, pictures) compose to narratives that convey more information than their parts—just like subclausal units compose to meaningful clauses that contain more information than the sum of their parts. We will say that clauses/pictures cohere with one another to form a narrative. In what follows we elucidate this idea by outlining how SDRT addresses the following three questions: (i) What are the coherence relations? (ii) What do they mean? (iii) How are they inferred? We end this section by showing how the answers to these questions allow us to improve on Abusch’s account of narrative sequencing in linguistic and pictorial narrative.

3.1 Coherence relations and narrative structure

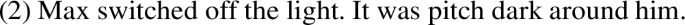

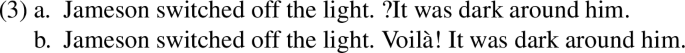

The first component of a formal theory of coherent narrative is a vocabulary of coherence relations that specify the different ways in which clauses can cohere with one another. For present purposes it is particularly important to note that the temporal sequencing of a narrative is a byproduct of establishing coherence relations.Footnote 12 The discourses below are cases in point.

In all three cases, the two clauses are linked by a cue phrase that indicates a coherence relation. Consider (52). The presence of because establishes that the pushing causes the falling. We indicate such causal relationships with the coherence relation Explanation. This is to say that (52) expresses a (short) narrative in which two events are reported (the pushing and the falling) and put in a particular relation: that one event causes the other. As causes must precede effects, we know that the pushing preceded the falling. Thus although in (52) the falling is described before the pushing, the fact that the two clauses relate by Explanation entails that the falling happened after the pushing.

Matters are similar in (53) and (54). In (53), the cue phrase so indicates that the falling caused the winning the race which is indicated by the coherence relation Result. In this case, the order of description matches the order of events, again due to the fact that causes must precede results. In (54) we see a third option for the order of events: overlap, as cued by the phrase while, which indicates the coherence relation Background. In this case, there is no causal relation. The falling was not caused by the being-away and the being-away was not caused by the falling. Instead, the being-away is presented as supplemental (‘backgrounded’) information. The relevance of this information may only become apparent once the discourse continues, e.g. as in (55):

This example is interesting for another reason as well. The clause in (55c) is marked (by the cue phrase so) to be the effect of some cause. But neither (55a) nor (55b) by themselves seem to properly describe this cause. It is both because Max fell and because John was, at the same time, away that he lied there alone. Thus, the proper way to structure (55) with coherence relations is to say that (55c) is an effect of the fact that Max fell and that John was away and the fact that these two temporally overlap (i.e. that they cohere by Background). That is:

In this structure, it is made explicit that the antecedent of the Result coherence relation encompasses the content of both (56a) and (56b) and that they cohere by Background.

There is more to say about the narrative structure induced by coherence relations. To wit, coherence relations fall into two broad classes: subordinating relations and coordinating ones.Footnote 13 The intuitive distinction is that subordinating relations add further information to an event that is already under discussion (e.g. by introducing a sub-event or adducing further properties of the event, its agents, themes or sub-events) whereas coordinating relations ‘move the narrative onward’ to a new event under discussion. Roughly put, coordinating relations move the narrative to a new scene whereas subordinating relations flesh out the current scene. (As we will discuss in due time, this distinction is especially evident in pictorial discourses.)

Of the relations seen so far, Explanation and Background are subordinating (they add an explanation or supplemental information) and Result is coordinating (it moves the narrative to a new event: the effect of the current one). Other subordinating relations include Elaboration (adducing a sub-event) and other coordinating ones include Narration (moving to a new event that is temporally close to the previous one) and Continuation (moving to a new event that is thematically related to the previous one).

It is customary to graph the coherence structure of a narrative by letting horizontal lines represent coordinating relations and vertical lines represent subordinating relations. The following toy examples illustrate this.

Contrast these structures with the tree representation of (56).

This structure makes explicit that the antecedent of the Result relation includes (56a), (56b) and the fact that they cohere by Background. The vertical/horizontal graphing expresses that Background is subordinating and Result is coordinating; the dashed lines indicate the complex antecedent of Result.

As observed by Polanyi (1985) the distinction between coordinating and subordinating relations is important for the interpretation of anaphora. When extending a narrative with a clause containing an anaphor, its only available attachment sites are in those segments that are accessible from the last segment in the narrative by traversing subordinating relations—but binders behind coordinating relations are inaccessible. For example, when one continues the discourses (57) or (59), one may resolve anaphora only to binders in the last segment. This is why the following discourse sounds odd.Footnote 14

In contrast, when continuing (58), one may resolve anaphora to binders in (58b) and (58c).

If one uses the notational convention that coordinating relations are graphed horizontally and subordinating ones are graphed vertically, then the accessible segments are exactly the segments on the right-most branch of the graphed narrative structure. Hence this constraint is known as the Right Frontier Constraint (Polanyi, 1985; see Hunter and Thompson, 2022 for recent discussion).Footnote 15

The right frontier constraint also governs which segments of the prior discourse are available to attach a new segment by a coherence relation. Consider the following variant of (60):

The only possible interpretation of (61) is that John had the dessert after he went dancing. It is not possible to interpret this discourse as (61d) continuing on (61b), in spite of this being what common sense would prefer. This is, again, due to the fact that (61b) is not on the right frontier of the discourse (61a,b,c). When continuing this discourse, anaphora can only attach to binders on the right frontier and new discourse segments can only cohere with segments on the right frontier.

So far, we have merely discussed coherence relations as a purely descriptive means to explicate the narrative structure of a discourse. We turn now to how they contribute to the pragmatic meaning of a discourse and afterwards to how one pragmatically infers narrative structure.

3.2 Coherence and meaning

Coherence relations are used to impose a narrative structure on clauses. The meaning of these clauses can be given in the form of DRSs (and later, when we discuss pictures, as PicDRSs). For example, (52a) and (52b) are interpreted as follows.Footnote 16

In the context of describing a narrative structure, we will also refer to the interpreted forms of individual clauses (i.e. DRSs) as elementary discourse units of a narrative narrative (in contrast to complex discourse units which are formed by connecting two discourse units by a coherence relation). Observe that these logical forms do not yet contain the information contributed by because, namely that \(e_2\) is the cause for \(e_1\) (and hence in particular that \(e_2\) precedes \(e_1\)). This information is obtained by composing the two DRSs to form a complex Explanation unit. Inspired by Montogovian semantics, the composition function is the meaning postulate assigned to the coherence relation Explanation. Meaning postulates map two DRSs to a new DRS that represents the information that the two clauses are connected by a particular relation. The following is the postulate for Explanation.

where \(K_1\) and \(K_2\) are DRSs, \(e_1\) and \(e_2\) are their respective main eventualities, \(\oplus \) is simple DRS composition (i.e. \(\langle U_1,C_1\rangle \oplus \langle U_2, C_2\rangle = \langle U_1\cup U_2, C_1\cup C_2\rangle \)), \(\prec \) is temporal precedence, and \(\textit{cause}_{e_2,e_1}(e)\) means that e is the eventuality that \(e_1\) causes \(e_2\). This eventuality e is introduced by the composition function and is the main eventuality of the DRS \(\llbracket \)Explanation\(\rrbracket (K_1,K_2)\). We can leave a theory of causality to the world model; for current purposes, cause eventualities are simply the eventualities expressed by the verb ‘cause’.

Now, when composing DRSs with \(\oplus \), one resolves (by the usual methods from DRT) conditions of the form \(x_2 = ?\). However, one must take care to respect the right frontier constraint and thus ?’s from \(K_2\) may only be bound to referents in \(K_1\) if they were introduced in a DRS on the right frontier. This constraint can be formalised by introducing additional DRT-conditions associating binders with the eventuality that introduced them. We elide this here for readability.

In (62), the main eventualities of the two clauses are \(e_1\) and \(e_2\), respectively, so interpreting (52) as Explanation(52a,52b) delivers the desired interpretation as the event described in the latter clause precedes and causes the event described in the former.

Note that it is important to introduce the cause eventuality e when computing the compositional meaning of Explanation. This is because by connecting two discourse units by Explanation, one forms a new, complex discourse unit that itself can cohere with other discourse units. But the compositional semantics of Explanation refer to the main eventualities of the discourse units it connects; so also complex discourse units must be assigned an eventuality. An example will help to clarify the point.

Here, John oversleeping caused him to miss his flight. But neither him oversleeping nor him missing his flight by themselves caused him to buy an alarm clock. Rather, that him oversleeping caused him missing the flight is what caused him to buy an alarm clock. This is represented in the annotated discourse structure: (63b) and (63c) cohere by Explanation and this complex segment coheres with (63a) by Explanation. To compute the compositional semantics of the latter Explanation relation, its second argument needs to have a main eventuality (as the meaning postulate for Explanation refers to the eventualities of both parts). By the semantics of Explanation given above, this is the eventuality that (63c) caused (63b). This yields the intuitive interpretation of the example.

The point is general: whenever we give the compositional semantics of a coherence relation, we need to make sure to specify the main eventuality of the complex discourse units formed by this coherence relation. This is because such complex units can be again composed further by composition functions referencing the main eventuality of their parts. We called this the discourse composition problem in Sect. 1.

With this in mind, we can analogously give meaning postulates for the coherence relations seen so far. Solving the the discourse composition problem by postulating eventuality arguments in complex discourse units is implicit in Asher and Lascarides (2003), but we make it an explicit part of the meaning postulates.

That is, in brief, Result is like Explanation with inverted causal-temporal order; Background contributes that two events (temporally) overlap; Elaboration that the second event is part of the first; Continuation contributes that the DRSs are about a common topic (see Asher and Lascarides, 2003 for details); and Narration is like Continuation and adds that the main eventualities occur in close succession.Footnote 17

Now we can define the notion of a segmented DRS (SDRS). The core idea is that all segments in a discourse are labelled (with lowercase Greek letters used as variables for labels) and that these labels are the arguments of coherence relations. So, for example, if \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) are labels for discourse segments, then we can formally state that they are related by Explanation as \(\textit{Explanation}(\alpha ,\beta )\). Crucially, relations between segments are themselves segments, so \(\textit{Explanation}(\alpha ,\beta )\) would receive its own label \(\gamma \) that then can be the argument of further discourse relations. In generality, we can define the notion of a segmented DRS as follows.

Definition 1

(SDRS) An SDRS is a triple \((\Pi ,\mathcal {F},L)\) where \(\Pi \) is a set of label variables, \(L \in \Pi \) and \(\mathcal {F}\) is a function with domain \(\Pi \) such that for any \(\pi \in \Pi \), either:

-

1.

\(\mathcal {F}(\pi ) = K\) for some DRS K.

-

2.

\(\mathcal {F}(\pi )\) is a conjunction of formulas of the form \(R(\alpha ,\beta )\), where \(\alpha ,\beta \in \Pi \) and R is a coherence relation.

\(\mathcal {F}\) induces a graph-structure on \(\Pi \). Say that an SDRS is well-formed if this structure is a tree like the ones described in the previous section (i.e. there is a unique root label \(\pi _0\) and the graph has no circles). If \(\mathcal {K}\) is a well-formed SDRS with root label \(\pi _0\), the semantic content of \(\mathcal {K}\) is \(\llbracket \pi _0\rrbracket \).

With these definitions, we have not only a mere descriptive labelling for how coherence relations structure a narrative, but a formal semantic theory of what a complex narrative means. With the compositional meaning postulates assigned to the coherence relations, we obtain narrative meanings that go well beyond the mere sum of their parts.

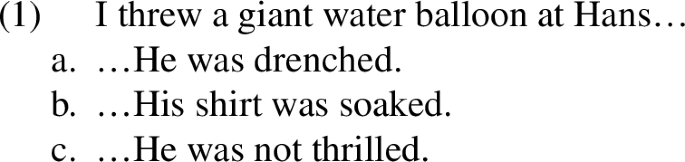

3.3 Inferring coherence relations

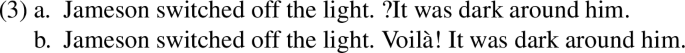

Many of the examples discussed in the previous sections, in particular (52)–(57), contain cue phrases that allow us to determine an associated coherence relation (e.g. because cuing Explanation and particularly cuing Elaboration). But in many cases we need to determine the correct coherence relation without explicit cuing. For example, dropping the cue because from (52) results in the example (64) which is still most naturally interpreted with Explanation.

The coherence relation makes (again) visible that the pushing happened before the falling, despite the falling being described earlier in the discourse. Note, however, that this interpretation of (64) is merely the most natural one, by which we roughly mean the interpretation produced as a first-glance assessment of the discourse. What is the most natural interpretation is subject to revision by further context. One can, for example, continue (64) with But this is not why he fell (cancelling the reading as Explanation) or extend (64b) with while he was on the ground to establish temporal succession.

Moreover, there is not always the most natural interpretation. The following example appears to be multiply ambiguous.

Depending on what is known about Amy and Lisa, it could be that Amy leaving caused Lisa to cry (Result) or that Lisa’s crying caused Amy to leave (Explanation) or that Amy left and Lisa cried for unrelated reasons (Continuation).

SDRT takes into account such facts about cancellation, revision and ambiguity to provide a model of how and why particular coherence relations are inferred. The idea is to formalize principles for pragmatic enrichment expressing the commonsense reasoning patterns leading to the ‘most natural’ interpretations. A guiding idea in phrasing these principles is that they should state the most plausible and most coherent interpretations given imperfect information. For example, if there is a salient way to read one event as causing another (e.g. that pushing someone might result in them falling), one interprets them as causally connected by assigning the relations Explanation or Result (Schlöder, 2018, ch. 7).

Asher and Lascarides (2003) formalize such principles in a default logic in which one can phrase defeasible conditionals \(p > q\) (paraphrased: ‘if p then normally q’). Their logic has the following properties that make it appropriate for the task at hand.

-

If p and \(p> q\), then infer q only if \(\lnot q\) is not the case (\(\lnot q\) defeats the conditional).

-

If p and \(p> q\), then infer q only if there are no r and s such that r, \(r > s\) and \(q,s\models \bot \) are the case (\(r> s\) clashes with \(p>q\)).

-

But more informative premisses win clashes, i.e. if p, \(p> q\), r and \(r>\lnot q\) all are the case and also \(p \models r\), but \(r\not \models p\), then infer q.

Phrasing the pragmatic principles using the conditional > ensures (i) that their conclusions can be overridden by additional information (defeating a conclusion); (ii) that when there are multiple conflicting principles in play, the interpretation remains ambiguous (no conclusions are drawn in clashes); and (iii) more detailed information can sway an ambiguity. See Asher and Lascarides (2003) and Lascarides and Asher (2009) for details on and further justification of this logic.

As an example for pragmatic enrichment, we can now formalize the principle that possible causes are typically interpreted as being causes as follows.Footnote 18

where the predicate cause describes a causal relation between two events and \(\Diamond \) is alethic possibility. These pragmatic principles are always to be read as universally closed, i.e. the formulae in (66) apply to all R, \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \). For example, (66a) applies when we are in a situation where we have \(R^?(\pi ,\lambda ) \wedge \Diamond \textit{cause}(e_\lambda ,e_\pi )\), where \(R^?\) is a placeholder indicating that \(\pi \) and \(\lambda \) are to be connected by some coherence relation. But it would also apply when we have a concrete coherence relation for R, e.g. \(\textit{Background}(\pi ,\lambda ) \wedge \Diamond \textit{cause}(e_\lambda ,e_\pi )\) to infer (ceteris paribus) that in addition to Background, the segments labelled by \(\lambda \) and \(\pi \) are connected by Explanation.Footnote 19 This is so in the following example, showing that it is possible to interpret two segments by assigning multiple relations.

The most natural interpretation here is that the speaker painted the barn because (previously) it was an ugly red, but also that the being an ugly red state overlapped the painting event (i.e. that the barn had no colours in between and the speaker painted over the ugly red). The temporal consequence of Explanation (that causes precede effects) is that the barn being red extends in time to sometime before the time index of the painting event.

However, not all coherence relations can be paired up. So, we can also include principles that constrain the possible interpretations. For example, the same two segments cannot be both connected by Explanation and Result, as causation ever only goes in one direction. In fact, there is something else wrong with pairing these two relations: Explanation is subordinating and Result is coordinating. But one cannot pair a subordinating with a coordinating relation, as it makes no sense for the same segment to add to a scene and also move to a new scene. Txurruka (2003) expresses this principle for pragmatic interpretation as in (68), where the predicates coord and subord describe a coherence relation to be coordinating and subordinating, respectively.

Like all other pragmatic principles, this is to be read as universally closed. That is, whenever we infer in the default logic that we have two segments, connected by two relations where one is coordinating and the other is not, the principle (68) leads to a contradiction.

Adopting this principle ensures that the principles for Explanation and Result clash.Footnote 20 That is, if there is equally good reason to believe that \(\alpha \) can cause \(\beta \) and that \(\beta \) can cause \(\alpha \) one infers neither Explanation nor Result. Arguably, this is the case in (65). Note however that it is not always desirable for certain principles to be clashing, as sometimes we want some principle to take precedence over another one. To achieve this, it is useful that more informative premisses win clashes. We exploit this when stating our principle for interpreting ESSs below.

Pragmatic principles are typically still not sufficient to determine the full coherence structure of a discourse. In SDRT, one proceeds as follows: consider all possible assignments of coherence relations that are compatible with the information inferred by the pragmatic principles. From these possible assignments, select the most coherent ones via a mechanism that grades coherence; this is known as the principle to maximise discourse coherence (Asher and Lascarides, 2003). The details would lead us afield here, but the intuitive idea is that consistent structures in which all anaphora are resolvable without violating the right frontier constraint are more coherent; and among these, structures that maximise the number of coherence relations (so the narrative is rich) while minimising the number of labels (so the structure is flat) are more coherent.

3.4 Narrative sequencing

We now proceed to show how we can build on the previous three sections to account for narrative sequencing in linguistic and pictorial narrative. This will serve as a preview of the next section, where we detail how our pragmatic principles are Super Pragmatic: they can apply regardless of the medium in which a narrative is interpreted, while nevertheless respecting the genius of each medium.

Our analysis begins with an appropriate pragmatic principle for the interpretation of eventive-stative sequences (ESSs). Note that there is no single coherence relation that is distinctively associated with ESSs (pace Asher and Lascarides, 2003 who associate ESSs with Background) and therefore, not surprisingly, there is no particular temporal order that is distinctively associated with ESSs (pace Kamp and Rohrer, 1983). The examples (45) and (46), repeated here with annotation, show that ESSs can at least support interpretations as temporal precedence and temporal overlap.

Although there is no particular coherence or temporal order that is distinctively associated with ESSs, inspection of the data reveals that the possible interpretations correspond to one of the subordinating relations (like Explanation and Background).Footnote 21 Reading an ESS as Result (a coordinating relation) sounds odd even if there is, in principle, a potential causal reading of the event and the state; recall (48) and (50), repeated below, where a causal reading is expected given world knowledge reasoning and yet it’s not available:Footnote 22

This leads us to suggest the following generalization, formalized as a pragmatic principle in SDRT.

Adding an axiom like (69b) to the generalization in (69a) ensures that the contribution of the aspectual information in (69a) takes precedence over any potential causal information. Specifically, (69a) says that ESSs are typically subordinating the state and (69b) says that causal information cannot by itself override this default. This is because the premiss of (69b) is more informative than just \(\Diamond \textit{cause}(e_\alpha ,e_\beta )\). In particular, then, (69b) wins clashes with the principle in (66) to infer Result.

This consequence of the analysis is particularly important for ESSs in which one may see a plausible causal relation between the described event and the described state. Consider again (48) and (50) above. In these examples, a Result interpretation (water balloon causing wetness; biting causing death) seems highly plausible on the face of it, but the stativity of the second part of the sequence seems to conflict with such an interpretation. Formally, letting \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) label the eventive and the stative, respectively, we take this to mean that \(\Diamond \textit{cause}(\alpha ,\beta )\) is a premiss available for computing the interpretation of these examples. According to our pragmatic principle for Result in (66), this would normally allow us to infer \(\textit{Result}(\alpha ,\beta )\). However, according to our pragmatic principle for ESSs in (69), it follows from this that \(\textit{subord}(Result )\) which is not the case, as Result is coordinating. Thus, the two principles clash.

Due to the fact that more informative premisses win clashes and the antecedent of (69b) is more informative than the one of (66), we infer that whatever coherence relation joins \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) must be subordinating. This means that in the most natural interpretations of the ESSs in (48) and (50), the eventive coheres with the stative by a subordinating relation. Now also taking into account the principle in (68), which states that two segments cannot be connected by both subordinating and coordinating relations, it follows that in the most natural interpretations, Result is ruled out. When the second part of a sequence is another eventive, however, as in the alternatives ‘got wet’ and ‘died’, the principle (69) does not apply and nothing stands in the way of interpreting the sequences as Result.Footnote 23

Note that the foregoing does not mean that in an ESS the eventive and stative always have to cohere with a subordinating relation. As the principles in (69) are also phrased as default conditionals, they can be cancelled by defeating or clashing information. One salient way to do so is to add explicit cuing to the discourse that defeats the defaults in (69). For example, in the following modifications of (48) and (50):

These cases are naturally and unproblematically interpreted as Result, in particular as the wetness temporally succeeding the throwing and the death succeeding the bite. The explicit cuing with the phrases therefore and as a result, respectively, enforces this interpretation and simply cancels the application of (69).Footnote 24

Now, in contrast to Result, the coherence relations Explanation and Background are subordinating, so they are not in similar conflict with the principle (69). As a matter of fact, we agree with Asher and Lascaride’s (2003) observation that ESSs are typically read as Background (i.e. one typically uses a stative to describe the situation in which an event unfolds). A paradigm example is (71):

To infer Background in such and other examples, we use the following principle.Footnote 25

That is, when interpreting an ESS we first infer subordination by the principle (69) from which we may infer overlap by (72). This suffices to obtain the desired interpretations of (48) and (50) as Background (i.e. as event and state overlapping). This is because SDRT includes a general principle that the necessary consequences of a coherence relation are typically sufficient to infer it (see Lascarides and Asher, 2009, 145ff). The instance of this principle relevant for present purposes is the following one, stating that the necessary consequence of Background (i.e. overlapping eventualities) are typically sufficient.

Together with our principle for Explanation in (66), we can now also derive the correct interpretation of (67), repeated here.

This is an ESS, so by (69) we infer that the eventive coheres with the stative by subordination. As above, this rules out an interpretation as Result (the ugly red was not the result of the painting). Conversely, something being an ugly color is a possible reason to paint it, so the principle for Explanation in (66) allows us to infer Explanation. Finally, the principle in (72) applies as well, allowing us to infer overlap and from there, via (73), Background. Thus the most natural interpretation of (67), according to our pragmatic principles, is indeed Explanation and Background meaning that the ugliness of the previous coat of paint was the speaker’s reason to paint over it.

This is how our pragmatic principles vindicate Kamp and Rohrer’s Aspect Hypothesis in (47), repeated below:

We infer Background (and hence, temporal overlap) by a multi-step process that first applies (69), then (72) and finally (73). That these are distinct steps has a subtle but important upshot. When the inferences to Background or even overlap are cancelled (by defeat or clash), this need not mean that the inference to subordination is defeated as well.Footnote 26 This is the case in examples where the most natural reading is only Explanation and does not include Background (i.e. there is strict temporal precedence between cause and effect). Here is such an example:

Again, this is an ESS, so by the principle (69) we infer subordination. However, the principle (72) to infer overlap is defeated here, as commonsense knowledge entails that one cannot simultaneously be out jogging and taking a shower.Footnote 27 However, similar knowledge entails that exercising is a possible reason for later taking a shower. So the principle for Explanation in (66) licenses the interpretation as Explanation.

Note that it is important for the interpretation of (74) that (69) applies and subordination is inferred. Otherwise, interpretations with coordinating relations would compete with the inference towards Explanation here; e.g. the interpretation as Narration where one went jogging after the shower. To see this, compare (74) with an analogous eventive-eventive sequence.

In this case, the interpretations as Explanation (jogging being the reason for showering) and Narration (the speaker showering and then going jogging) are, arguably, equally natural. In (74), however, there appears to be a clear preference for the Explanation reading. This distinction is explained by the principle (69) applying to (74)—ruling out the coordinating relation Narration—but not to (75).

In sum, we have shown how to account for the pragmatics of narrative sequencing in linguistic discourse. We end this section by showing an important virtue of this analysis: without further modifications, we can explain why narrative sequencing in pictorial discourse differs from its linguistic counterpart. Recall that the pictorial narrative in (49), repeated below, is naturally interpreted as exemplifying Result, whereas the prima facie equivalent linguistic narrative in (48), also repeated below, is odd for some speakers precisely because it cannot be interpreted as exemplifying Result.

To explain this difference, we appeal to Abusch’s hypothesis in (40), repeated below.

According to this hypothesis, both segments of (49) are stative. This means that the principle in (69), stating that eventive-stative sequences typically subordinate the state, does not apply. Thus—since the first picture depicts a possible reason for the state in the second picture—nothing prevents us from applying the pragmatic principle in (66) for inferring Result. This prediction generalizes to all pictorial narratives: if a causal interpretation is plausible, then we predict that this will be the likely interpretation. If, on the hand, a causal interpretation is not plausible, as in (38), repeated below, then some other axiom (in this case (72)) will be at play and make the correct prediction (in this case that Background holds).

An anonymous reviewer points out to us that there is a salient alternative to our account. Once we take on board the assumption that the logical form of a discourse is obtained by principles of pragmatic enrichment, we could conceive of a principle that takes stative representations of information (sentences or pictures) and enriches them to eventive information from whence one could continue with the full power of the eventive/stative distinction also in pictorial discourses. This is prima facie appealing, but not obviously compatible with the formal assumptions of our framework. The principles of pragmatic enrichment can only add information to the formal surface features of its input, not remove or revise any of them (only information obtained from the surface features by default inference can be revised). This would require a radical revision to our formal framework. There is a second option to achieve this. Instead of revising the stative information, one may add to the stative term a new, eventive eventuality term and make the eventive one the main eventuality of the discourse segment. This would require a similarly radical revision, as it breaks with the principle that the main eventuality of an elementary discourse segment is determined by the grammar. We are hence reluctant to pursue either option.

Thus, once we make the assumptions that we do—inherited from SDRT—and agree with Abusch’s diagnosis of stativity, we are forced to treat pictures as statives for discourse interpretation. This is not to say, of course, that it is not possible to pragmatically read a stative as contributing eventive information. But this would happen at a later stage of the interpretive process than the determination of discourse structure.

In any case, it is not a disadvantage to have to treat pictures as immutably stative, but in fact an advantage. By using pragmatic principles that operate differently on statives vs eventives, one can replicate Abusch’s results for narrative sequencing in pictorial discourse, while also correctly predicting contrasts like (48) and (49). However, we note that this proposal assumes a Super Pragmatics in which coherence relations can be applied to pictorial discourses as much as to linguistic discourses. The goal of the next section is to flesh out this assumption and show how we could thereby address the aforementioned questions in Sect. 1 concerning co-reference in pictorial discourse, while also solving the discourse composition problem.

4 Super pragmatics

The coherence relations, and their meaning postulates, are typically thought to be referencing domain-general cognitive principles for structuring information (e.g., Hobbs, 1985,1990; Kehler, 2002, 2019).Footnote 28 Indeed, the idea that discrete packets of information are related to complex structures, going beyond the sum of the packets, is not intrinsically tied to linguistic discourse. For example, Cumming et al. (2017) explore the role that coherence relations play in the interpretation of film. More recently, Newton-Haynes and Altshuler (2019) have explored the coherence structure of ballet mime, while Grosz et al. (2021) have motivated a semantics of emoji by first considering the sort of coherence relations that they allow when mixed with language. Building on this research programme, we suggest to use the same vocabulary of coherence relations in linguistic and pictorial discourse. However, the meaning postulates we described in the previous section contribute DRS conditions in the language of event semantics. It is not clear how to evaluate such conditions applied to non-linguistic information. We now show how to define the conditions contributed by the meaning postulates for pictorial discourse. The core idea is that the pictorial content of a PicDRS can take the place of a main eventuality.

4.1 Extending SDRT to pictures

We can maintain the received vocabulary of coherence relations and adapt the received definition of Segmented DRSs to a definition of Segmented PicDRSs by simply replacing DRSs with PicDRSs. However, the meaning postulates of the coherence relations cannot be straightforwardly applied to PicDRSs. In these postulates, the coherence relations are defined to contribute a meaning that depends on the eventualities of the DRSs that are composed. PicDRSs have no obvious main eventualities—there is, say, no main verb from which one could compute such an eventuality.

However, following Abusch’s insight that pictures are stative depictions of the world, one may treat the picture content of a PicDRS to be its main eventuality. To be more precise, a PicDRS contains a token of the picture that gave rise to the PicDRS. This token is the main eventuality of the PicDRS. If, at a different point in the narrative, the same picture occurs again and is parsed into a PicDRS, the main eventuality of that PicDRS will be a different token of that same picture. Also if some meaning postulate requires us to copy a PicDRS, the copy will be type- but not token-identical to the original. In particular, it will contain a new token of the same picture. This is in line with how main eventualities are treated in SDRT: the main eventualities of different SDRSs are always distinct tokens (Asher and Lascarides, 2003).

Thus, we need to define the logical vocabulary needed for stating the meaning postulates to apply to pictures. Note that if our goal were merely to represent the discourse structure of a pictorial discourse, this would not be needed. We could assemble PicDRSs by the methods surveyed in Sect. 3 and use DRS conditions like \(\textit{overlap}(p_1,p_2)\) or \(\textit{cause}_{p_1, p_2}(p)\), replacing eventuality terms with pictures, as demanded by the meaning postulates for the coherence relations. This is because DRT makes a principled distinction between the representation of a discourse and its evaluation. One can assemble DRSs, representations of discourses, without specifying how to evaluate DRS-conditions in a world model. But if one wants to compute meanings of narratives, as is our goal, one must define how to evaluate these conditions. This means we have to say how to evaluate in a model whether two pictures \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) overlap or whether a picture p is depicting a causal relationship between \(p_1\) and \(p_2\). We now turn to this task.

Recall that we have assumed to have a projection function \(\pi \) that takes a world and a viewpoint so that a picture p has semantic value 1 at a world w and a viewpoint v iff \(\pi (w,v)\) resembles p. Naturally, a viewpoint is not just a location, but a location at a time, so it makes sense to temporally order viewpoints. We can then explain the temporal predicates in the meaning postulates.

-

\(\llbracket p_1 \prec p_2\rrbracket ^{w,v} =1\) iff there are viewpoints \(v_1\), \(v_2\) such that \(v_1\) is before \(v_2\), \(\pi (w,v_1) = p_1\) and \(\pi (w,v_2) = p_2\) and \(p_1\) is not token-identical to \(p_2\).

-

\(\llbracket \textit{close}(p_1,p_2)\rrbracket ^{w,v}=1\) iff there are viewpoints \(v_1\), \(v_2\) such that \(v_1\) is temporally close to \(v_2\),Footnote 29\(\pi (w,v_1) = p_1\) and \(\pi (w,v_2) = p_2\).

-

\(\llbracket \textit{overlap}(p_1,p_2)\rrbracket ^{w,v}=1\) iff there are viewpoints \(v_1\), \(v_2\) such that \(v_1\) is simultaneous with \(v_2\), \(\pi (w,v_1) = p_1\) and \(\pi (w,v_2) = p_2\).

For the definition of temporal succession, we require that that the two argument pictures cannot be token-identical. This is for the following reason. Given a picture p, it is possible that there are two distinct viewpoints, at distinct times from which the world resembles p. According to the definition of \(\prec \) without the final conjunct, it would then follow that \(p\prec p\), which is absurd. Although it is possible for the world to resemble the same picture at different times, a single picture token cannot be interpreted in a narrative to represent a state that precedes itself. However, two tokens of the same picture can occur in a narrative. Consider the following sequence:

This can be interpreted as a simple narrative in which a person stands still, stumbles, and then stands still again. The first and third picture are the same, but the PicDRSs for these pictures will contain different tokens \(p_1\) and \(p_3\) of this picture. In the interpretation of the narrative, it will be the case that \(p_1 \prec p_3\) but it cannot be the case that \(p_1 \prec p_1\). The added clause requiring that the two arguments of \(\prec \) cannot be token-identical ensures that this is the case. We thank an anonymous reviewer for discussion on this point.

Now, note that the viewpoints \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) in these definitions may ‘look’ at very different parts of the world—all that matters when these viewpoints are taken. Recall our pictorial example for an overlapping interpretation.

Saying that these two depictions temporally overlap means that there is a way to view the world showing the first picture and that one could also, at the same time, view the world showing the second picture. There may be many viewpoints showing the first picture for which there is no simultaneous viewpoint showing the second (and vice versa). All that is required is that the temporal interval in which one could show the first picture overlaps with the interval in which one could show the second picture.

In addition, we define the predicate, part-of, as follows:

-

\(\llbracket \textit{part-of}(p_1,p_2)\rrbracket ^{w,v}=1\) iff \(p_1\) could be obtained from \(p_2\) by ‘zooming in’ or ‘altering perspective’.

For example, the following pictorial discourse, taken from Brian Selznick’s The Invention of Hugo Cabret, is interpreted with the coherence relation Elaboration.

Interpreting this as Elaboration entails that the part-of relation holds between the first and second picture (specifically that the second is part of the first). In this case, the part-of relation validates that the second picture is obtained from the first by ‘zooming in’. This establishes in particular a fact about co-reference: that the eye depicted in the second picture is the man’s eye depicted in the first picture. Note that ‘zooming in’ can reveal information that was not previously visible; here, this is a reflection in the man’s eye. The part-of relation entails that in the world perceived from the viewpoint of the first picture, the reflection is in the man’s eye as well (even if this is not visible from this viewpoint).

Another example for a part-of relation is the following pictorial discourse:

In this case, the part-of relation validates that the second picture is obtained from the first by ‘altering perspective’Footnote 30 rather than ‘zooming in’. This again establishes a co-referential fact: that these are the same mugs. Like ‘zooming in’, ‘altering perspective’ can reveal information that was not previously visible. Here, this is the artwork seen in the second picture. The part-of relation entails that in the world that is perceived from the viewpoint of the first picture, the depicted mug has the artwork and a handle (even if this is not visible from this viewpoint).

It is worth noting that the part-of relation between pictures is more narrow than the part-of relation between eventualities. For example, the event that John is eating is a part of the event that John has dinner. But not every depiction of John having dinner will contain as a part a depiction of him eating (because he may be depicted as engaged in other dinner activities, e.g. drinking). But this is as it should be. When we depict John having dinner (in a way where he is not depicted as actively eating) and then depict John as eating, these should not be interpreted as Elaboration, as the two depicted states do not in fact overlap.

Depictions of the world have less potential to be abstract than linguistic descriptions of the world. While we can linguistically describe the activity dinner in the abstract and elaborate with parts of the dinner, a depiction of dinner will by necessity display a particular activity. We can only pictorially elaborate on this particular activity, not on the abstract activity dinner. Despite this limitation, as seen in the examples above, a picture can still be said to elaborate on another and this can be an important part of their pragmatic interpretation (e.g. as related to co-reference).

When we display John having dinner and then display another dinner-related activity, the two pictures stand in another relation familiar from SDRT: Topic. When treating Topic relations, however, we face the composition problem. Recall the Narrative Compositionality Constraint that we derived from the Discourse Composition Problem in Sect. 1.