Abstract

The aim of this work was to study the effect of ceramics particles addition (SiO2, ZnO, TiO2) on the ultraviolet (UV) aging of poly(lactic acid) nonwovens fabricated using electrospinning method. The resistance to aging is a key factor for outdoor and medical applications (UV light sterilization). Nonwovens were placed in special chamber with UV light. Changes of physicochemical properties were recorded using differential scanning calorimetry and attenuated total reflection Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. The fibers’ morphology was studied by using scanning electron microscopy. Obtained results clearly showed that only PLA fibers with ZnO particles gained an increase in UV resistance. The paper presents a description of structural changes taking place under the influence of UV aging processes and describes the mechanisms of this process and the effect of ceramic addition on the lifetime of such materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Biodegradable and bio-based polymers have recently drawn more and more attention in several applications, including composites [1,2,3], packaging [4] and medicine [5]. Polyesters are considered to be one of the most important classes of biomaterials [6]. Poly(lactic acid) (PLA), linear polyester, is extensively tested in medicine and tissue engineering, due to its biodegradability, non-toxicity and biocompatibility [7, 8]. PLA is a thermoplastic relatively easy to process. In addition, its mechanical properties are similar to commonly used synthetic polymers. Physicochemical properties of PLA depend on a stereoisomeric form of polymer [9]. Lactic acid (LAc), a repetitive unit of PLA, consists of two optical isomers: D(−)LAc and L(+)LAc. Homochiral PLA is a semi-crystalline, isotactic polymer (PLLA and PDLA). Polymerization of D- and L-LAc mixture leads to the formation of heterochiral, atactic PLDLA with amorphous properties.

The PLA is susceptible to hydrolysis and under the conditions of the human body enzymatically decomposes into LAc, which occurs naturally in living organisms. In the citric acid cycle, LAc is converted into carbon dioxide and water [10]. Thanks to good mechanical properties that allow PLA to endure the stresses applied in a human body; it is commonly used in implants for bone fixation and absorbable surgical sutures [11].

In tissue engineering, PLA has been utilized as material for drug delivery microspheres [12, 13] and scaffolds [14, 15] for cell growth. It is required for scaffold to support regeneration of the tissue in the place of the defect and then degraded when the healing is completed. PLA could be easily made in various forms and shape, including microspheres and fibers with diameter that ranges from nanometers to micrometers. The main advantage of forming 2D and 3D fibrous scaffolds is a strong anisotropy of properties that allows to adapt material to specific requirements, a very high surface area, and the possibility of creating complex microstructures with specific pores and density [16]. Thanks to the ability to control the physicochemical properties of fibers; also through the degree of crystallinity, modifications of the volume and surface of the fibers, it is possible to modulate the biological response [17].

Here, we report the fabrication of PLA fibers modified with inorganic particles (ZnO, SiO2, TiO2) using the electrospinning method (ES). This technique involves electrostatic forces to generate polymer solution jets and induce the ejection through a spinneret. An electrical potential is applied between the tip of a needle and a grounded collector. In order for the polymer jet to be ejected, the electric field must overcome the surface tension of the drop. The fiber morphology is influenced by many parameters, especially concentration of the polymer, molecular weight, distance between tip and collector, solvent content, flow rate, applied voltage and temperature [18,19,20].

PLA exhibits disadvantages in some key aspects, such as hydrolysis and degradation under UV light exposure [21], what limits its applicability. The resistance to aging is a key factor for outdoor and medicine applications (packaging, stitches, bandage, sterilization). UV stability of PLA-based materials has attracted a lot of attention recently [21,22,23]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies in the literature regarding the influence of UV exposure on the properties of PLA nanocomposite fibers. We hypothesized that modification of fibers with inorganic particles (SiO2, ZnO and TiO2) can affect the stability of PLA. ZnO and TiO2 are effective absorbers of UV [24, 25] and are commonly used as UV-screen agents in sunblocks. Zhang reported that ZnO nanoparticles can stabilize poly(butylene succinate-co-butylene adipate) matrix and hinder the photodegradation of polymer [26].

Experimental

Materials

Poly(lactic acid) (PLA, IngeoTMBiopolymer 3251D) with molecular weight M = 70,000–120,000 g mol−1 was purchased from NatureWorks LLC, USA. Dichloromethane (DCM) and dimethylformamide (DMF) were obtained from Avantor Performance Materials Poland S.A., Gliwice, Poland. Ceramic particles: ZnO particles (1 μm), SiO2 nanaoparticles (12 nm) and TiO2 nanoparticles (100 nm) were purchased from Merck KGaA, Germany.

Preparation of PLA-based solutions for electrospinning process

PLA-based solutions for electrospinning process (ES) with concentrations 11, 13 or 15% (w/v) were prepared by dissolving polymer in binary-solvent system of DCM and DMF (2.5:1 v/v or 3:1 v/v). Solution was stirred for 24 h using magnetic stirrer at about 50 °C. Next, ceramic particles powder (ZnO, TiO2 or SiO2) was added and solution was ultrasonicated for 10 min. Next, PLA solution was stirred for another 24 h. The concentration of inorganic particles was 6 mass%, beyond that content solution retained its rheological properties.

Electrospinning process

PLA-based nonwoven was formulated through electrospinning process (ES) using apparatus constructed at Department of Biomaterials and Composites, AGH, Poland. The solution was sonicated for 10 min before injection into 10 mL syringe. A high voltage–power supply (0–25 kV) was used to generate an electric field between needle (0.7 mm) and cylindrical, rotating collector (width: 5 cm) covered with aluminum foil. The system was encased in a special chamber that allowed to perform ES process at constant temperature (50 °C) and humidity (10%). The spinning time of nonwovens was 1 h.

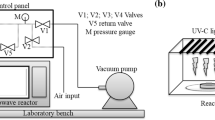

Aging test

The aging test was carried out by exposing PLA and PLA-composite nonwovens to UV light. Samples were placed into the chamber equipped with UV-C lamp (35 W cm−2). Air circulation was forced in the chamber (Fig. 1) to remove ozone, which was forming from oxygen by UV irradiation during aging test. The presence of ozone could accelerate degradation of PLA nonwoven. The equivalent of exposure time to UV radiation was calculated from the average exposure the Earth to Sun’s UV radiation (62 W m−2 [27, 28]). One hour in the aging chamber equals 5645 h of exposure to solar radiation, assuming that the Sun shines continuously and all UV irradiation reaches the Earth’s surface. The samples were exposed to UV light for 15 min, 1 and 4 h.

Characterization

Surface morphology of PLA nonwovens and composites fibers was studied using scanning electron microscope (SEM, Nova NanoSEM 200) with an accelerating voltage of 18 kV. Samples were mounted onto special holders and coated with conductive carbon layer prior to SEM analysis. Images analysis software (ImageJ) was applied to determine fiber’s diameters and distribution of fibers’ directions in nonwovens. For each material, 30 fibers were measured. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were taken using DSC1 (Mettler Toledo) in dynamic mode (atmosphere: nitrogen, 200 mL min−1, heating and cooling rates: 10 K min−1, temperature range: − 30–180 °C). Samples (6 mg) were sealed in aluminum pans and placed in the equipment sample chamber. Fourier-transform infrared spectra (ATR-FTIR) of PLA and composite nonwovens before and after different times of UV light aging were recorded using Tensor 27 equipment with ATR mode (diamond crystal), in range 4000–600 cm−1, at resolution 4 cm−1. For each sample, 64 scans were performed.

Results and discussion

Optimization of electrospinning parameters

Diameter, quality and direction of fiber arrangement can be controlled by parameters such as polymer concentration in solution, solvents, electrical field voltage, or collector rotation speed. The needle-collector gap influences jet flying time and evaporation of the solvents. Binary-solvent system (DCM and DMF) was used to fabricate PLA-based nonwovens. The SEM images were used to evaluate the quality (morphology and diameter) of obtained PLA fibers. All of the fibers had smooth and defect-free morphology. It was observed that ratio of solvent had a great influence on the fiber diameter (Fig. 2). Thinner fibers were obtained using ratio 2.5:1, regardless of the polymer concentrations. The other optimized parameter was gap between tip of needle and collector, and polymer concentration. As expected, the diameter of the fibers decreased with increasing needle-collector distance, as shown in Fig. 2a. This was due to the longer time that the solvents had to evaporate. Also, in most cases, increasing the polymer concentration resulted in obtaining fibers with increased diameters (Fig. 2b). Based on the SEM images, the following parameters were selected to obtain fibers modified with ceramic particles: concentrations of PLA—13%, gap between tip of needle and collector—5 cm, ratio of DCM and DMF—2.5 to 1.

Impact of UV aging on fibers morphology

The morphology of the composite fiber was examined using SEM (Fig. 3). The pure PLA fibers exhibited smooth and defect-free surface, as shown in Fig. 3a. However, diameter distribution was wide, from 1.5 to 5.5 μm, with average diameter 2.91 μm (Fig. 4a). It was found that ceramic additives caused a reduction in average fiber diameter. For SiO2, TiO2 and ZnO, it was 2.12, 1.40 and 2.79 μm, respectively, as well as narrowing the distribution (Fig. 4b–d). Figure 3b, c shows that adding SiO2 and TiO2, in contrast to ZnO, changed the morphology significantly. In both cases, the fiber surface was wrinkled and defected.

The morphology of fibers after UV degradation was evaluated as well. Exposure of PLA fibers to irradiation for 10 min and 1 h did not significantly affect their morphology. After 4 h, broken and bent fibers were observed (Fig. 3a). A similar phenomenon occurred in composites with SiO2 and TiO2 (Fig. 3b, c). The PLA/ZnO fibers behaved differently under the UV exposure. Changes in morphology were much more significant. Fibers fused together and the original microstructure was completely destroyed after 4 h, as shown in Fig. 4d. In addition, the change in the distribution of the fiber alignment was also the most significant (Fig. 4d). Before the degradation, fibers were arranged almost parallel to each other, but after degradation crossed fibers appeared (Fig. 3d). However, broken fibers weren’t observed even after 4 h of UV exposure.

Fibers in PLA nonwoven were arranged parallel to the direction of the collector rotation in major part, as shown in Fig. 4a (y-axis). The aging process resulted with a slight change, the chart became a little wider, but in the range not exceeding 5% after 10 min of UV exposure. With longer aging time, the fibers broke during relaxing and changed the orientation, which is clearly visible on the graph for 4 h of UV exposure. This phenomenon was intensified even more in the case of composite fibers modified with TiO2 and SiO2 (Fig. 4b, c). Addition of ceramic particles did not promote receiving oriented nonwovens. They generate additional stresses in the fiber. When fiber broke under the UV radiation, it relaxed and changed its direction to a more favorable energetically. This effect is the most significant for PLA/SiO2 nonwoven.

The presence of ceramic particles led to larger deviations in the orientation of the nonwovens. This effect was most significant in the case of fibers with the addition of SiO2 particles. The spectrum of distribution of fibers collected on the collector during the ES process was the widest. The aging process also evidently led to a change in the direction of the fiber.

Impact of UV aging on fibers thermal properties

Figure 5 shows DSC curves of pure PLA fibers and fibers with ceramic particles addition. PLA is a crystalline polymer. For pure PLA, three phase transitions were clearly visible on the DSC curve (Fig. 5a): glass transition with recrystallization (63.0–69.3 °C), cold recrystallization (77.0–94.4 °C), recrystallization before melting and melting (159.1–172.5 °C). These transformations were very clear, followed by each other at certain intervals of temperature. This demonstrated that well-oriented and structurally homogeneous fibers formed the nonwoven layer.

The UV degradation induced structural changes in polymer, what is directly translated into thermal properties of PLA, which can be seen in Fig. 5a. The energy of phase transformations decreased with the aging time. A decrease in glass transition temperature (Tg) is due to the less need for fiber to go into a highly elastic state.

Ceramic’s additions have a significant impact on the degradation process under the UV radiation (Fig. 5b–d). It seems that TiO2 even accelerated the degradation of polymer structure. Addition of ceramic’s particles significantly reduced the temperatures of transformation processes and their energy. After 4 h in aging chamber, the transformations were almost invisible on the curve. Only ten degree separated melting from glass transition with recrystallization. Energy of melting decreased as the sample holding time in aging chamber increased. Similar situation was observed for fibers modified with SiO2. The exception here is ZnO; in this case, the drop is insignificant. The drop of melting energy after 4 h wasn’t that significant. This is consistent with SEM images; PLA/ZnO fibers were the least degraded. The exact values of phase transitions’ energies are shown in Fig. 6.

Significant differences were also noted in the case of recrystallization energy. Over time, the recrystallization energy decreases, with the exception of PLA/ZnO nonwoven. In this case, a slight increase in energy was observed. After 4 h, the energy value doubled. The opposite trend was noted for the composite fibers modified with TiO2 particles. After the initial increase, the transformation energy dropped significantly.

Melting of PLA/ZnO composite began at a slightly higher temperature compared to pure PLA and other composites. The energy also remained constant throughout the aging test. This can be explained by the greater proportion of the crystalline phase in the polymer. For this reason, no cold recrystallization was observed. ZnO nanoparticles may have acted as place of nucleation starting and promoted the crystallization of PLA.

The positive impact of ZnO particles on PLA stability was also demonstrated by the lack of a significant increase in glass transition energy. In fact, the value remains almost the same for 4 h of degradation. This may indicate improved stability of the composite fibers. In other cases, including pure PLA, the energy value increases several times. The most dynamic changes were observed for TiO2.

TiO2 particles are used as a material absorbing UV radiation in sunlight [29, 30]. Therefore, it was expected that this type of nanoparticles should provide the best protection against photodegradation. Even though the effectiveness of UV absorption of TiO2 is very high, TiO2 at the same time emits photoelectrons that can be involved in the production of peroxides and other reactive oxygen species (ROS—reactive oxygen species) [31].

Also, SiO2 did not improve the stability of the polymer against UV irradiation. Of all the ceramic particles tested, SiO2 is the most transparent to UV radiation. Phase transition energies also fell the fastest in this case. Also, the presence of SiO2 in the fibers promoted their degradation due to the possibility of UV radiation passing through the SiO2 grains (present on the surface and inside the fiber). In addition, the PLA/SiO2 nonwoven had the lowest cold crystallization energy. This may indicate a large amount of the crystalline phase.

Impact of UV aging on fibers chemical structure

The effect of UV aging on the chemical structure of PLA-based fibers was examined by the FITR-ATR method. ATR spectrum of PLA nonwoven is shown in Fig. 7. Typical bands of PLA can be found in the range 3000–2800 cm−1 (asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations in CH3, CH2 and CH groups), at 1382.0 cm−1 (symmetric bending vibration of C–H) and 866.1 cm−1 (stretching vibration of C–C). Another characteristic peak at 1750.8 cm−1 corresponded to C=O groups [32]. Bands at 1181.3 cm−1 and 1084.4 cm−1 can be assigned to C–O–C vibrations of ester groups [33]. After aging changes in spectra weren’t significant. There was no appearance of new peaks as the result of polymer degradation. Only decrease in some band intensity was observed (Fig. 7a).

The spectra of different composite nonwovens looked similarly to this made of pure PLA (Fig. 7b–d). The main bands of ceramic fillers could be overlapped and covered by the bands from the polymeric matrix. In addition, method (ATR) chosen to study the effect of photodegradation on composites chemical structure measures only a thin layer having direct contact with the crystal. The infrared analysis of PLA after UV aging test did not show any significant changes of the spectrum or formation of new bands. The characteristic bands of the PLA decreased their intensities, due to the photodegradation of the polymer structure (smaller graphs show peaks for C–H stretching vibrations in PLA chains). In the case of pure PLA fibers, the intensity of bands in the range 3000–2800 cm−1 clearly decreased after just 10 min of UV exposure. However, an intensity of whole spectra did not change in a significant way even after 4 h (Fig. 7a). For composites with ZnO, an intensity of the C–H stretching vibrations decreased more gradually over time. After 10 min, the change seems to be less rapid than in the case of pure PLA (Fig. 7b). Again, the decrease in peaks in this area was also observed for PLA composites with TiO2 and SiO2. However, in these cases, the changes are much more significant, and after 4 h of UV exposure, the bands almost completely disappeared. Polymer degradation is also indicated by gradual disappearance of peaks in the whole range of spectra (Fig. 7c, d).

The UV absorbers in the form of ceramic nanoparticles were added to slow down the UV degradation of poly(lactic acid). Only ZnO protected the polymer matrix against photodegradation.

Conclusions

The nanocomposite fibers based on poly(lactic acid) were produced successfully by an electrospinning method. The parameters of process (concentration of polymers, gap between needle and collector, ratio of solutions) were optimized to obtain defect-free microfibers. It turned out that the chosen method is very sensitive to changing process conditions. The diameter of the fibers can be easily controlled by increasing the distance between the needle and the collector. The longer solvent evaporation time results in smaller diameter fibers. The addition well dispersed ceramic powders to PLA-based solution completely changed nature of the produced fibers. Ceramic materials, known as UV absorbent, were incorporated into polymer matrix to slow down the aging process. Stability of PLA is a key aspect for using this biopolymer as packaging material and in tissue engineering. The protective effect was noticed only for ZnO particles. The addition of ZnO significantly increased the proportion of crystalline and amorphous phases in the fabricated PLA-based fibers and changed the mechanism of the photodegradation. Similar impact was noticed in the case of TiO2 and SiO2. These additives significantly changed the microstructure of the nonwovens and accelerated matrix degradation. They caused cracking and breaking of fibers.

References

Pozo Morales A, Güemes A, Fernandez-Lopez A, Carcelen Valero V, De La Rosa Llano S. Bamboo-polylactic acid (PLA) composite material for structural applications. Materials. 2017;10:1286.

Huang L, Zhang X, Xu M, Chen J, Shi Y, Huang C, et al. Preparation and mechanical properties of modified nanocellulose/PLA composites from cassava residue. AIP Adv. 2018;8:025116.

Murariu M, Dubois P. PLA composites: from production to properties. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;107:17–46.

Connolly M, Zhang Y, Brown DM, Ortuño N, Jordá-Beneyto M, Stone V, et al. Novel polylactic acid (PLA)-organoclay nanocomposite bio-packaging for the cosmetic industry; migration studies and in vitro assessment of the dermal toxicity of migration extracts. Polym Degrad Stab. 2019;168:108938.

Davachi SM, Kaffashi B. Polylactic acid in medicine. Polym Plast Technol Eng. 2015;54:944–67.

Manavitehrani I, Fathi A, Badr H, Daly S, Negahi Shirazi A, Dehghani F. Biomedical applications of biodegradable polyesters. Polymers. 2016;8:20.

Tajbakhsh S, Hajiali F. A comprehensive study on the fabrication and properties of biocomposites of poly(lactic acid)/ceramics for bone tissue engineering. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2017;70:897–912.

Santoro M, Shah SR, Walker JL, Mikos AG. Poly(lactic acid) nanofibrous scaffolds for tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;107:206–12.

Srisuwan Y, Baimark Y. Mechanical properties and heat resistance of stereocomplex polylactide/copolyester blend films prepared by in situ melt blending followed with compression molding. Heliyon. 2018;4:e01082.

Farah S, Anderson DG, Langer R. Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications—a comprehensive review. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;107:367–92.

da Silva D, Kaduri M, Poley M, Adir O, Krinsky N, Shainsky-Roitman J, et al. Biocompatibility, biodegradation and excretion of polylactic acid (PLA) in medical implants and theranostic systems. Chem Eng J. 2018;340:9–14.

Qi F, Wu J, Li H, Ma G. Recent research and development of PLGA/PLA microspheres/nanoparticles: a review in scientific and industrial aspects. Front Chem Sci Eng. 2019;13:14–27.

Shi X, Cui L, Sun H, Jiang N, Heng L, Zhuang X, et al. Promoting cell growth on porous PLA microspheres through simple degradation methods. Polym Degrad Stab. 2019;161:319–25.

Grémare A, Guduric V, Bareille R, Heroguez V, Latour S, L’heureux N, et al. Characterization of printed PLA scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: characterization of printed PLA scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2018;106:887–94.

Magiera A, Markowski J, Menaszek E, Pilch J, Blazewicz S. PLA-based hybrid and composite electrospun fibrous scaffolds as potential materials for tissue engineering. J Nanomater. 2017;2017:1–11.

Armentano I, Bitinis N, Fortunati E, Mattioli S, Rescignano N, Verdejo R, et al. Multifunctional nanostructured PLA materials for packaging and tissue engineering. Prog Polym Sci. 2013;38:1720–47.

Granados-Hernández MV, Serrano-Bello J, Montesinos JJ, Alvarez-Gayosso C, Medina-Velázquez LA, Alvarez-Fregoso O, et al. In vitro and in vivo biological characterization of poly(lactic acid) fiber scaffolds synthesized by air jet spinning: in vitro and in vivo biological characterization of PLA. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jul 3]. Available from http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/jbm.b.34053.

Casasola R, Thomas NL, Trybala A, Georgiadou S. Electrospun poly lactic acid (PLA) fibres: effect of different solvent systems on fibre morphology and diameter. Polymer. 2014;55:4728–37.

Huang C, Thomas NL. Fabricating porous poly(lactic acid) fibres via electrospinning. Eur Polymer J. 2018;99:464–76.

Lasprilla-Botero J, Álvarez-Láinez M, Lagaron JM. The influence of electrospinning parameters and solvent selection on the morphology and diameter of polyimide nanofibers. Mater Today Commun. 2018;14:1–9.

Salač J, Šerá J, Jurča M, Verney V, Marek AA, Koutný M. Photodegradation and biodegradation of poly(lactic) acid containing orotic acid as a nucleation agent. Materials. 2019;12:481.

Gardette M, Thérias S, Gardette J-L, Murariu M, Dubois P. Photooxidation of polylactide/calcium sulphate composites. Polym Degrad Stab. 2011;96:616–23.

Janorkar AV, Metters AT, Hirt DE. Degradation of poly(L-lactide) films under ultraviolet-induced photografting and sterilization conditions. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;106:1042–7.

Reinosa JJ, Docio CMÁ, Ramírez VZ, Lozano JFF. Hierarchical nano ZnO-micro TiO2 composites: high UV protection yield lowering photodegradation in sunscreens. Ceram Int. 2018;44:2827–34.

Sullalti S, Totaro G, Askanian H, Celli A, Marchese P, Verney V, et al. Photodegradation of TiO2 composites based on polyesters. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem. 2016;321:275–83.

Zhang Y, Xu J, Guo B. Photodegradation behavior of poly(butylene succinate-co-butylene adipate)/ZnO nanocomposites. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2016;489:173–81.

Lean JL, Rottman GJ, Kyle HL, Woods TN, Hickey JR, Puga LC. Detection and parameterization of variations in solar mid- and near-ultraviolet radiation (200–400 nm). J Geophys Res Atmos. 1997;102:29939–56.

Rafieepour A, Ghamari F, Mohammadbeigi A, Asghari M. Seasonal variation in exposure level of types A and B ultraviolet radiation: an environmental skin carcinogen. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2015;5:129.

Mohr LC, Capelezzo AP, Baretta CRDM, Martins MAPM, Fiori MA, Mello JMM. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles applied as ultraviolet radiation blocker in the polylactic acid bidegradable polymer. Polym Test. 2019;77:105867.

Lv J, Yang J, Li X, Chai Z. Size dependent radiation-stability of ZnO and TiO2 particles. Dyes Pigments. 2019;164:87–90.

Fu L, Hamzeh M, Dodard S, Zhao YH, Sunahara GI. Effects of TiO2 nanoparticles on ROS production and growth inhibition using freshwater green algae pre-exposed to UV irradiation. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;39:1074–80.

Chieng BW, Azowa IN, Wan Md Zin WY, Hussein MZ. Effects of graphene nanopletelets on poly(lactic acid)/poly(ethylene glycol) polymer nanocomposites. AMR. 2014;1024:136–9.

Sibeko B, Choonara YE, du Toit LC, Modi G, Naidoo D, Khan RA, et al. Composite polylactic-methacrylic acid copolymer nanoparticles for the delivery of methotrexate. J Drug Deliv. 2012;2012:1–18.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Grant No 15.11.160.019 (Faculty of Materials Science and Ceramics, AGH University of Science and Technology).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kosowska, K., Szatkowski, P. Influence of ZnO, SiO2 and TiO2 on the aging process of PLA fibers produced by electrospinning method. J Therm Anal Calorim 140, 1769–1778 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08890-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-019-08890-6