Abstract

The twenty-first century started with many downsizing applications. This important trend in the engine technology has been constantly developed. There are questions about limits and on the other hand new solutions in the face of new materials, tribological discovery, lubrication oils, turbo- or supercharging, new control electronic system of the engine run, higher accuracy in designing, etc. Some of parameters of thermodynamics of working cycle and thermal load according to the downsizing engine parameters were considered in this article. The downsizing impacts on fuel economy and emission were analysed, too. The investigations were carried out with own measured data (i.e. pressure inside inlet manifold, temperature of engine wall) as well as data from references (for example material properties) and at the end the simulations were done. The essential achievements of the work are (a) downsizing factor (DSF) was defined first time in this article (nobody before), (b) because of possibility of exceeding thermal load in piston (as an example engine part) the changes of DSF has to be restricted to almost 0.95 giving changes of 0.85 for base cylinder diameter and 0.90 ratio of base volume for stroke, (c) the main goal of downsizing to reduce CO2 emission was results of all tests but it show only 10% benefit, and (d) it is possible to optimise the downsizing technology. So, the next research work will be focused on changes of super- and turbocharging as well as lean mixture combustion for better optimisation of downsizing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The engine technology named downsizing occupies a significant position in the worldwide idea of reducing carbon dioxide emission as well as saving up fuels. It saves manufacturing costs per power unit, too.

The idea of downsizing the engine (which means reducing main dimensions of the engine) reducing the swept volume with mainly the same or higher torque and power of the engine has been well known since the 1990s [1–3]. However, there are numerous limitations of this technology and they might be overcome only when new advanced solutions are available [4, 5].

In gasoline engines, essential limitations are as follows: knocking, thermal and mechanical loads of the engine components, response time of turbocharging as well as reliability and durability of the engine parts [6].

In case of diesel engines, the most important limitations of applying the technology of downsizing are thermal loads and consequently the right type of cooling as well as the emission of particulate matter and nitrogen oxides which are in contradiction with the idea of reducing CO2 [7, 8].

The main task for engineers working on downsizing is to control ignition and combustion process, e.g. the controlled homogeneous auto-ignition supercharged engine (CHAISE), to control timing and lift of valves—the variable valve timing (VVT), to control recovering energy—the exhaust gas recirculation (EGR), variable and mixed charging—the VS or variable supercharging and turbocharging (VST), to change compression ratio—the variable compression ratio (VCR), to control the procedure START/STOP, switching off cylinders (the dynamic downsizing), emission reduction, e.g. the gasoline direct injection (GDI). There are also so called indirect interventions, e.g. applying alcohol fuels to gasoline engines taking into consideration higher resistance against knocking and larger speed of fuel burning which improves thermal efficiency [9].

Reducing dimensions of the combustion chamber with simultaneous growth of mean effective pressure definitely influences thermodynamics of combustion process as well as it puts into consideration the thermal load of the engine components.

By that project, I would like to join the discussion about limitations of downsizing from the thermodynamic standpoint. The conclusions which are in accordance with the title of the article have been presented after the author’s own research based on multi-variants computer simulation, carried out at the Division of Motor Vehicles and Internal Combustion Engines, the Wroclaw University of Technology (Poland).

Thermal load of combustion engine

Thermal load which is an ambiguous notion is referred both with heat transfer and the temperature or its gradients. According to Prof. Wisniewski [10], overall thermal load of the engine is usually understood as a stream of heat in the selected conditions of the engine operation following the formula (1) mentioned below:

where Q is the heat transfer, Q HV is fuel heating value, B o is dose of fuel in time unit and ξ is the coefficient of heat utilisation in combustion chamber.

Local thermal loads, relating to individual parts of the engine, characterise heat exchange on their surfaces as well as heat penetration into metal depth. They depend on

-

heat conductivity,

-

geometry of the combustion chamber and the relation of dimensions,

-

velocity of combustion gases inside the chamber,

-

course of the burning process.

The analysis of thermal loads in the engine as the whole object as well as in its separate components is based on different kinds of heat exchange conditions such as conduction, convection, radiation and diffusion [4, 10–12].

The thermal conduction is observed within homogeneous substance (solid state) under the influence of temperature gradients. The quantity of heat Q, transferred in the definite direction, is formulated by Fourier’s law (2).

where λm is the thermal conductivity of medium; s is thickness of layer of medium; A is surface area of the barrier for heat transfer; T 1, T 2 are temperature on surfaces of studied barrier and τ is the time.

The thermal conductivity λm is an experimental factor which characterises this kind of heat exchange for solid substances (including metal) and it is related to temperature and pressure. For example AK12 (popular aluminium alloy used in engines) can be described as follows [13]:

The convection is the mechanism of heat exchange which dominates in liquids and gases. This is transportation of heat through moving particles which cause heat transfer by contacting each other or the barrier. The measure of convection can be the speed of movement of particles which is variable in the section of flow: from stormy in the central part, across laminar, until to achieve motionless layer on the surface of the barrier.

The convective heat transfer coefficient αk characterises the heat exchange by convection. This coefficient expresses the quantity of heat passed from gas or liquid to the unit of surface area of the solid barrier at the unit of difference of temperature between medium and the barrier (Newton’s law of cooling).

where αk is the convective heat transfer coefficient; A is surface area of the barrier for heat transfer; T 1, T 2 are temperature on surfaces of studied barrier and τ is the time.

The coefficient αk is an empirical value and can be expressed by criteria numbers as follows: Nusselt’s Nu, Prandtl’s Pr, Reynold’s Re.

An example of empirical qualification of coefficient αk in the combustion chamber within the engine is formula given by Woschni [14, 15].

where D is the cylinder diameter, w is average speed of air–fuel mixture in combustion chamber, p(φ i ) is temporary value of pressure inside combustion chamber, T(φ i ) is temporary value of temperature inside combustion chamber and φ i is the value of crank angle of turn of crankshaft in the working cycle of engine.

The thermal radiation is the type of heat transfer which depends on properties of absorbing irradiated surface, its emissivity and the transparency. In the combustion chamber, the following processes can be distinguished:

-

exchange of energy by radiation among the chamber element (walls),

-

emission of hot exhaust gases including the flame in the chamber,

-

emission of radiation of particulate matters as products of fuel burning in exhaust gases.

These phenomena are complex and in case of combustion chamber they depend on the chamber geometry, temperature changes as well as the oscillation of phenomena following the working cycle of the engine. The example of empirical formula defining emissivity of the flame is shown below (6) [16]:

where εf(φi) is the relative emissivity of the flame

where p(φi) is the temporary pressure inside combustion chamber, l p is average distance of flame in combustion chamber.

where V is the volume of burning space, A k is area of the combustion chamber

The heat diffusion expresses the quantity of thermal energy passed between mediums divided with barriers. The diffusion consists of the mentioned earlier forms of heat transfer and in case of the combustion engine it might include convection of air–fuel charge, radiation of exhaust gases, conduction in the barrier of the chamber walls, convection in coolant and convection and radiation to the ambient from the engine outside surfaces. It happens in the block of the engine. Shape and multi-layers of the barrier are of great importance in this case. It can be observed in the cylinder liner (fixed in the block), which consists of bas layer and anti-wear layer. The average value of cross section can be calculated as an average logarithmic of inner and external diameters—see (9) and (10) for Q, the heat transfer coefficient is created as supplementary and it depends on convection and conduction processes (11)

where A m average surface area of cross section of barrier, l length of the cylinder liner, r z external radius of the cylinder liner, r w inner radius of the cylinder liner, k z supplementary coefficient of the heat transfer, T 1, T 2 temperature on surfaces of the studied barrier, τ time, α1, α2 convective heat transfer coefficients for zones of 1 and 2 in relation to the barrier, s i thickness of layer, called ‘i’ within the barrier, λ i thermal conductivity of layer named ‘i’ within the barrier.

The specificity of the engine run is the reason why the heat transfer is an unsteady process which means that changes of temperature lead to the unbalanced heat relation between entry Q 1 and exit Q 2:

For the unit dimensions of the studied parts of the engine, the heat can be qualified according to the formula as shown below (13):

where c p is specific heat for constant pressure, dx, dy, dz are changes of unit dimensions of studied parts, ρ is density of material and dT is the changes of temperature in the changes of time of dτ

If the heat spreads into one dimension only (e.g. to the “x”), the formula (13) might be presented as Fourier’s equation for unsteady state (14).

and the expression (15) is called coefficient of thermal diffusion.

According to Woschni’s definition [14, 15], heat load in the combustion engine requires qualification of temperature changes of air–fuel charge (T) at space with closed valves and for some assumptions, connected with air–fuel mixture:

-

air–fuel mixture is in thermal equilibrium at any time,

-

air–fuel mixture can be treated as perfect gas,

-

combustion chamber is closed space from thermodynamic standpoint (the same quantity of air–fuel mixture at any time).

The fundamental equation to calculate thermodynamics of perfect gas is as follows:

where p is the pressure of gas, V is volume of burning space, T is temperature of air–fuel mixture, b is current coefficient of change of moles number for air–fuel mixture, n 1 is total number of moles of air–fuel mixture at the beginning of compression cycle and MR is universal gas constant.

At any time of the engine run, expressed with crank angle of crankshaft (φ i ), temperature T can be marked according to the formula (17):

The universal gas constant is an independent index. Factor p(φ i ) specifies pressure course following pV-diagram, measured at the test stand in a laboratory. The remaining factors depend on constructional parameters of the engine, e.g. the swept volume V(φi) which is changed according to formula (18) and in which the compression ratio is of high importance as well as the clearance volume:

where V k is the clearance volume, ε is compression ratio, L is length of connecting rod and R is the crank radius.

The current values of changes of mole number of air–fuel mixture is the function of changes of quantity of fresh charge which is indirectly dependant on the filling ratio and that one depends on the swept volume:

where δ is the coefficient of changes of mole number of fresh charge, γ is molar coefficient of residual gases

where ηv is the charging ratio, V s is swept volume, p ot is ambient pressure, L t is theoretical quantity of mole of air, B o is dose of fuel in time unit, MR is universal gas constant and T ot is the ambient temperature.

The similar dependence (relations to cylinder diameter and stroke) can be observed for coefficients of heat convection and emissivity [13, 14, 17].

Therefore, it is obvious that the downsizing technology affects thermodynamic factors of the engine working cycles and its operational parameters.

Downsizing technology

In general meaning, downsizing technology should be understood as a process of reduction of any size in machinery to get expected result, e.g. mass reduction or better performance, etc. When referring to the combustion engine downsizing stands for reducing swept volume with mainly the same or higher torque and power of the engine for reduction of CO2 emission and fuel consumption as well as to save manufacturing costs per power unit. I recognise three typical downsizing forms: changing cylinder diameter only, changing piston stroke only and changing both of them. The project presented here is aimed at examining the influence of changes of the downsizing factor (DSF), understood as relation of cylinder diameter to piston stroke on basic operating parameters of the engine. To fulfil the goal of the project, the matrix of changes of the DSF was created (Table 1). Many simulations were carried out whilst estimating the changes of, e.g. maximum temperature of air–fuel mixture, convective heat transfer coefficient, mean effective pressure, specific fuel consumption, emission of carbon dioxide.

Research was referred to the real engine Fiat 1.1 dm3 with following parameters: V s = 1108 cm3; D = 70 mm; S = 72 mm; P e = 40 kW/5500 rpm; M o = 88 Nm/3500 rpm; ε = 9.6; pressure at the beginning of compression 1.15 MPa.

That engine, assembled in car Fiat Seicento Sporting, was theoretically examined in the downsizing technology according to data matrix described in Table 1.

In the numerical research, many indexes were simulated depending on the DSF as follows: pressure of turbocharging, reduction of compression ratio, changes of cooling system by heat transfer from hot chamber walls to the fresh air–fuel mixture at the beginning of working cycle, etc.

Results

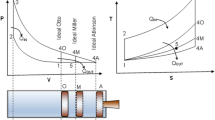

The research results of the downsizing simulation are presented in the relative scale which is the consequence of applying the same thermodynamic theory of combustion engine, the analysis of thermal loads, measuring techniques, etc (Fig. 1).

In Fig. 2, the line and the areas illustrate the changes of DSF in the range of 0% (lack of downsizing) in the left bottom corner of graph up to 50% (the strong downsizing) placed in the right upper corner. Together with the change of DSF, the increase of charging was analysed up to 44% which gave the same level of increasing pressure at the end of intake stroke and nearly 10% rise of pressure at the end of the compression. The compression ratio was reduced by about 18% and mechanical efficiency was improved by 4%. The fresh air–fuel mixture was about 40% less heated from the hot chamber walls. These downsizing interventions caused the growth of many parameters as follows: 4.4% for filling ratio, 18% for maximum pressure of the cycle with simultaneously the same temperature of the circulation (maximum value falls down about 1% only). The average effective pressure increased significantly—about 50%. The power of engine grew up by about 50%, too. Effective efficiency was improved by about 1.5% whilst the reduction of fuel consumption was observed at the same level.

The multi-case analysis was organised to report the possible optimisation of the downsizing technology. Only some results (as three-dimensional graphs) of study are introduced in this article.

There are the changes of power in function of changes of D* and S* (Fig. 3), the changes of specific fuel consumption versus D* and S* (Fig. 4), the changes of mean effective pressure (Fig. 5).

The graphs of thermal load factors versus DSF were also built as follows: the changes of convective heat transfer coefficient in relation to DSF (Fig. 6), the changes of heat flux through piston crown (Fig. 7) as well as the changes of emission of carbon dioxide in exhaust gases (Fig. 8).

In general revision of analysed thermal load parameters and engine operating indexes, the range of changes of diameter and stroke should be from 0.8 to 0.85.

Summary

In the global discussion of the reduction of CO2 emission as well as fuel consumption by combustion engines, concept of downsizing takes very important place.

The idea of engine modification with sustaining the engine operation performance or increasing power and torque in the same time is well known since the beginning of 1990s. There were technological solutions which are still developed to eliminate many technical limitations connected with downsizing.

The minimisation of size of engine with increasing break mean effective pressure has to be analysed from the thermal load’s point of view. So, there were researches carried out by the staff of the Wroclaw University of Technology in Poland. Some labs tests and multivariable simulations were organised to looking for downsizing optimum. All results were transformed to percentage scale to be relative for considered factors and parameters.

This project shows that in downsizing design, it is necessary to watch the thermal effects.

Based on the presented material, it is worth to consider downsizing from the range of 80–90% of bore and piston stroke changes, giving DSF equals 8:9. For these parameters effective power is essential higher than entry value up to 50%. The same result was estimated for heat flux through piston crown. The physical and chemical processes in the downsized engine were simulated for supercharging with 44% of increasing of pressure at the end of intake stroke, almost 10% rise of pressure at the end of compression, reduction of compression ratio of 18% to protect engine against knocking, etc. So, the thermal load of engine was recognised as well as operating engine indexes as dependent variables. For example the maximum temperature of charge during whole cycle was minimised of 1.5% and it gave reduction of total convective heat transfer coefficient αk of 6–8%. The results of supercharging and cooling were improving charging ratio of almost 5% and increasing pick of pressure of 18% as well as brake man effective pressure of 53%.

The main goal of downsizing to reduce CO2 emission was results of all tests but it show only 10% benefit.

So, the next research work will be focused on changes of super- and turbocharging as well as lean mixture combustion for better optimisation of downsizing.

Abbreviations

- A :

-

Surface area of the barrier for heat transfer

- A m :

-

Average surface area of cross section of barrier

- A k :

-

Area of the combustion chamber

- b :

-

Current coefficient of change of moles number for air–fuel mixture

- B o :

-

Dose of fuel in time unit

- c p :

-

Specific heat for constant pressure

- D :

-

Cylinder diameter

- D*:

-

Change of diameter D* = D downsizing/D start value

- dx, dy, dz :

-

Changes of unit dimensions of studied parts

- dT :

-

Temperature changes in the time interval dτ

- k z :

-

Supplementary coefficient of the heat transfer

- l :

-

Length of the cylinder liner

- l p :

-

Average distance of flame in combustion chamber

- L :

-

Length of connecting rod

- L t :

-

Theoretical quantity of mole of air

- M o :

-

Engine torque

- MR :

-

Universal gas constant

- n 1 :

-

Total number of moles of air–fuel mixture at the beginning of compression cycle

- p :

-

Pressure of gas

- p ot :

-

Ambient pressure

- P e :

-

Engine power

- p(φi):

-

Temporary pressure inside combustion chamber

- Q :

-

Heat transfer

- Q HV :

-

Fuel heating value

- R :

-

Crank radius

- r z :

-

External radius of the cylinder liner

- r w :

-

Inner radius of the cylinder liner

- s :

-

Thickness of layer of medium

- s i :

-

Thickness of layer, called ‘i’ within the barrier

- S :

-

Piston stroke

- S*:

-

Change of piston stoke, S* = S downsizing/S start value

- T :

-

Temperature of air–fuel mixture

- T 1, T 2 :

-

Temperature on surfaces of studied barrier

- T(φ i ) :

-

Temporary value of temperature inside combustion chamber

- V :

-

Volume of burning space

- V k :

-

Clearance volume

- V s :

-

Swept volume

- T ot :

-

Ambient temperature

- αk :

-

Convective heat transfer coefficient

- α1, α2 :

-

Convective heat transfer coefficients for zones of 1 and 2 in relation to the barrier

- γ:

-

Molar coefficient of the rest of exhaust gases

- δ:

-

Coefficient of changes of mole number of fresh charge

- ε:

-

Compression ratio

- εf(φ i ):

-

Relative emissivity of the flame

- ηv :

-

Charging ratio

- λ i :

-

Thermal conductivity of layer named ‘i’ within the barrier

- λm :

-

Thermal conductivity of medium

- ξ:

-

Coefficient of heat utilisation in combustion chamber

- ρ:

-

Density of material

- τ:

-

Time

- φ i :

-

Value of crankshaft angle of turn of crankshaft in the working cycle of engine

- w :

-

Average speed of air–fuel mixture in combustion chamber

- DSF:

-

Downsizing factor DSF = D*/S*

- rpm:

-

Revolution per minute

- CHAISE:

-

Controlled homogeneous auto-ignition supercharged engine

- VVT:

-

Variable valve timing

- EGR:

-

Exhaust gas recirculation

- VS or VST:

-

Variable super- and turbocharging

- VCR:

-

Variable compression ratio

- GDI:

-

Gasoline direct injection

References

Merker GP, Schwartz Ch, Teichmann R. Combustion engines development. Berlin: Springer; 2009.

Kuhlbach K, Mehring J, Bormann D, Friedfeld R. Zylinderkopf mit integriertem Abgaskrummer fur Downsizing-Konzept. Mag MTZ. 2009;69:286–93.

Smith A. Stroke of genius for gasoline downsizing. Ricardo Q Rev 2008;Q3.

Heywood JB. Internal combustion engine fundamentals. Singapore: McGraw-Hill; 1989.

Hiereth H, Prenninger P. Charging the internal combustion engine. New York: Springer; 2007.

Sroka ZJ. Thermodynamic cycle of combustion engine with hydrogen fuelling, JKONES 2007;14(3).

Andrade RDA, Faria EA, Silva AM, Araujo WC, Jaime GC. Heat of combustion of biofuels mixed with fossil diesel oil. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2011;106:469–74.

Robertis E, Moreira GF, Silva RA, Achete CA. Thermal behavior study of biodiesel standard reference materials. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2011;106:347–54.

Flierl R, Schmitt S, Kleiner G, Esch HJ, Dismon H. Univalve—a fully variable mechanical valve lift system for future internal combustion engines. Mag ATZ. 2011;04:34–9.

Wisniewski S. Thermal loads in combustion engines. Warsaw: Ed WKL; 1972.

Ambrozik A. An analysis of working cycles of four-stroke engines. Kielce: Kielce University of Technology; 2010.

Benson RA. The thermodynamics and gas dynamics of internal-combustion engines, vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1982.

Blair GP. Design and simulation of four-stroke engines. Warrendale: Ed SAE; 1996.

Grajnert J, Kwasniowski S, Sroka ZJ. Identification of heat transfer dynamic model for diesel engines. Proceedings of Motauto, vol 1. Sofia; 2000.

Guzzella L, Onder ChH. Introduction to modeling and control of internal combustion engine systems. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

Oppenheim AK, Kuhl AL, Packard AK, Hedrick JK, Johnson WP. Model and control of heat release in engines. Am J Engine Combust Flow Diagn SAE Pap. 1996;1157:15–23.

Ramos JI. Internal combustion engine modeling. New York: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation; 1989.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sroka, Z.J. Some aspects of thermal load and operating indexes after downsizing for internal combustion engine. J Therm Anal Calorim 110, 51–58 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-011-2064-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-011-2064-x