Abstract

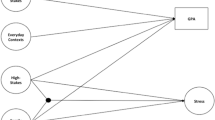

This study examines the relationship between perceived discrimination and self-reported proficiency in English and non-English languages among adolescent children of immigrants. Data from the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study was used. The average age of participants was 17.2 years; 1,494 were females and 1,332 were males. Among 2,826 participants, 61% reported Latin American and Caribbean national origin and 39% reported Asian national origin. Findings from probit regression analysis showed that adolescents who felt discriminated against by school peers were more likely to report speaking and reading English less than “very well”. On the other hand, adolescents who felt discriminated against by teachers and counselors at school or reported perceived societal discrimination were more likely to report speaking and reading English “very well.” The results suggest youth’s English, as opposed to non-English language, as the primary venue in which perceived discrimination influences youth’s linguistic adaptation. The findings further indicate that the direction and possible mechanisms of this influence vary depending on the source of perceived discrimination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Non-English language in this paper refers to the language, other than English, which a participant reports knowing, and speaking at home. The English versus non-English distinction appears to be less problematic than “native” versus “foreign” language distinction. Depending on the place of birth and parental nativity, some participants might consider English their “native” language. Depending on the length of stay in the United States, other participants might consider English their “foreign” language.

Portes and Hao (1998) defined a bilingual speaker as speaking English “very well” and speaking a non-English language “well” or “very well.” The present analysis extends this definition to bilingual proficiency and presents separate analyses for English or non-English languages. Because of the “parallel monolingualism”, or relative independence of two languages of bilingual adolescents (Caldas and Caron-Caldas 2002; Yeung et al. 2000), this strategy appears to be appropriate.

The results of the factor analysis indicated the one-dimensional structure of the perceived societal discrimination scale. The extracted Factor 1 was highly correlated with Item 1 (r = 0.78, p < 0.001), Item 2 (r = 0.79, p < 0.001) and Item 3 (r = 0.55, p < 0.001).

References

Alba, R., Logan, J., Lutz, A., & Stults, B. (2002). Only English by the third generation? Loss and preservation of the mother tongue among the grandchildren of contemporary immigrants. Demography, 39(3), 467–484.

Bean, F., & Stevens, G. (2003). America’s newcomers and the dynamics of diversity. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Caldas, S., & Caron-Caldas, S. (2002). A sociolinguistic analysis of the language preferences of adolescent bilinguals: Shifting allegiances and developing identities. Applied Linguistics, 23(4), 490–514.

Carhill, A., Suarez-Orozco, C., & Paez, M. (2008). Explaining English language proficiency among adolescent immigrant students. American Educational Research Journal, 45(4), 1155–1179.

Chiswick, B., & Miller, P. (1998). Language skills definition: A study of legalized aliens. International Migration Review, 32(4), 877–900.

Chiswick, B., & Miller, P. (2007). The economics of language: International analysis. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

CILS. (2005). The Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study. Center for Migration and Development. Retrieved from Internet on July 26th, 2005. WWW address: http://cmd.princeton.edu/cils.shtml.

Compas, B., Connor-Smith, J., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127.

Cummins, J. (1979). Cognitive/academic language proficiency, interdependence, the optimal age question and some other matters. Working paper on bilingualism, 19, 197–205.

Daykin, A., & Moffatt, P. (2002). Analyzing ordered responses: A review of the ordered probit model. Understanding Statistics, 1(3), 157–166.

Dornbusch, S. (1989). The sociology of adolescence. Annual Review of Sociology, 15, 233–259.

Edwards, J. (1985). Language, society, and identity. New York, NY: Basil Blackwell in association with Andre Deutsch.

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Felix, U. (2004). Performing beyond the comfort zone: Giving a voice to online communication. In R. Atkinson, C. McBeath, D. Jonas-Dwyer & R. Phillips (Eds), Beyond the comfort zone: Proceedings of the 21st ASCILITE Conference. Perth, Western Australia, 5–8 December: ASCILITE. Retrieved from Internet on May 14th, 2008. WWW address: http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/perth04/procs/contents.html.

Fisher, C., Wallace, S., & Fenton, R. (2000). Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29(6), 679–695.

Fishman, J. (1966). Language loyalty in the United States. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton.

Galindo, L. (1995). Language attitudes toward Spanish and English varieties: A Chicano perspective. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 17(1), 77–99.

Gans, H. (1977). Symbolic ethnicity: The future of ethnic groups and cultures in America. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2(1), 1–20.

Giles, H., Bourhis, R., & Taylor, D. (1977). Toward a theory of language in ethnic group relations. In H. Giles (Ed.), Language, ethnicity, and intergroup relations (pp. 307–348). London, UK: Academic Press.

Greene, M., Way, N., & Pahl, K. (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 218–238.

Hakuta, K., & D’Andrea, D. (1992). Some properties of bilingual maintenance and loss in Mexican background high-school students. Applied Linguistics, 13, 72–99.

Hakuta, K., & Diaz, R. (1985). The relationship between degree of bilingualism and cognitive ability: A critical discussion and some new longitudinal data. In K. E. Nelson (Ed.), Children’s language (Vol. 5). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hamers, J., & Blanc, M. (2000). Bilinguality and bilingualism (2nd Ed. ed.). United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Hernandez, R. (1993). When an accent becomes an issue: Immigrants turn to speech classes to reduce sting of bias. The New York Times, March, 2, 1993.

Kessler, R., Mickelson, K., & Williams, M. (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40(3), 208–230.

Lippi-Green, R. (1997). English with an accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States. New York, NY: Routledge.

McKay, S. L., & Wong, S. C. (1996). Multiple discourses, multiple identities: Investment and agency in second-language learning among Chinese adolescent immigrant students. Harvard Educational Review, 66(3), 577–608.

Mesch, G., Turjeman, H., & Fishman, G. (2008). Perceived discrimination and the well-being of immigrant adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 592–604.

Mossakowski, K. (2003). Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(3), 318–331. (special issue on race, ethnicity, and mental health).

Mouw, T., & Xie, Y. (1999). Bilingualism and academic achievement of first- and second-generation Asian Americans: Accommodation with or without assimilation? American Sociological Review, 64(2), 232–252.

Norton Pierce, B. (1995). Social identity, investment, and language learning. TESOL Quarterly, 29(1), 9–31.

Okita, T. (2002). Invisible work: Bilingualism, language choice and childrearing in intermarried families. Vol. 12 of IMPACT: Studies in language and society. Philadelphia, USA: John Benjamins.

Peal, E., & Lambert, W. (1962). The relation of bilingualism to intelligence. Psychological Monographs, 76, 1–23.

Pease-Alvarez, L. (2002). Moving beyond linear trajectories of language shift and bilingual language socialization. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 24(2), 114–137.

Portes, A., & Hao, L. (1998). E Pluribus Unum: Bilingualism and loss of language in the second generation. Sociology of Education, 71(4), 269–294.

Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Portes, A., & Schauffler, R. (1994). Language and the second generation: Bilingualism yesterday and today. International Migration Review, 28(4), 640–661. (special issue on the new second generation).

Powers, S., & Sanchez, V. (1982). Correlates of self-esteem of Mexican American adolescents. Psychological Reports, 51, 771–774.

Romero, A., & Roberts, R. (1998). Perception of discrimination and ethnocultural variables in a diverse group of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 641–656.

Rumbaut, R. (1994). The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review, 28(4), 748–794. (special issue on the new second generation).

Rumbaut, R., Massey, D., & Bean, F. (2006). Linguistic life expectancies: Immigrant language retention in Southern California. Population and Development Review, 32(3), 447–460.

Sinclair, K. (1971). The influence of anxiety on several measures of performance. In E. Gaudry & C. D. Spielberger (Eds.), Anxiety and educational achievement (pp. 95–106). Sydney, Australia: Wiley.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (1981). Bilingualism or not: The education of minorities (L. Malmberg & D. Crane, Trans.). Multilingual Matters 7. England: Multilingual Matters.

Stevens, G. (1985). Nativity, intermarriage, and mother-tongue shift. American Sociological Review, 50(1), 74–83.

Stevens, G., & Ishizawa, H. (2007). Variation among siblings in the use of a non-English language. Journal of Family Issues, 28(8), 1008–1025.

Stolzenberg, R., & Tienda, M. (1997). English proficiency, education, and the conditional assimilation of Hispanic and Asian origin men. Social Science Research, 26, 25–51.

Suarez-Orozco, C., & Suarez-Orozco, M. (2001). Children of immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behavior. Social Science Information, 13, 65–93.

Tseng, V., & Fuligni, A. (2000). Parent-adolescent language use and relationships among immigrant families with East Asian, Filipino, and Latin American backgrounds. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62(2), 445–476.

Wong, C., Eccles, J., & Sameroff, A. (2003). The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality, 71(6), 1197–1232.

Xu, M. (1991). The impact of English-language proficiency on international graduate students: Perceived academic difficulty. Research in Higher Education, 32(5), 557–570.

Yeung, A., Marsh, H., & Suliman, R. (2000). Can two languages live in harmony: Analysis of the National Education Longitudinal Study of 1988 (NELS88) longitudinal data on the maintenance of home language. American Educational Research Journal, 37(4), 1001–1026.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Ross Stolzenberg, Woody Carter and Anthony Orum for their useful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Medvedeva, M. Perceived Discrimination and Linguistic Adaptation of Adolescent Children of Immigrants. J Youth Adolescence 39, 940–952 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9434-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9434-8