Abstract

In this study, we investigated whether parental smoking-specific communication is related to adolescents’ friendship-selection processes. Furthermore, we investigated whether adolescents and their best friends influence each other over time, and what role parents play in this process. In the present study we used data from the Family and Health project in which at baseline 428 full families participated. In this 2-year, three-wave longitudinal study data were available from fathers, mothers, early adolescents (aged M = 13.4 years, SD = .50), and middle adolescents (aged M = 15.2 years, SD = .60). The majority of the participating adolescents were of Dutch origin (>95%). There was an almost equal distribution of boys and girls, and adolescents with lower, middle, and higher educational levels were equally represented. Analyses were conducted by means of Structural Equation Modeling. Results demonstrate that a high quality of the smoking-specific communication is related to a lower likelihood of adolescent smoking, whereas the frequency is positively associated with adolescent smoking. Both the quality and frequency of parental smoking-specific communication were related to adolescents’ selective affiliation with (non-)smoking friends. The findings suggest that parental smoking-specific communication is associated with adolescent smoking directly but also indirectly by influencing the friends the adolescents will associate with.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Worldwide, tobacco use is considered as the second major cause of death and the fourth most common risk factor for diseases (World Health Organization 2007). For the development of effective smoking-prevention programs, it is essential to establish which factors are associated with smoking behavior. In the present study we focused on two important socialization factors in the direct environment of adolescents, namely parents and friends. Social influences are assumed to be one of the core concepts in extensive list of risk and protective factors (see Petraitis et al. 1995).

As primary socializing agents, parents can exert an important influence on their offspring’s smoking behavior. Recent studies on the role of parents in the development of adolescents’ smoking have concentrated on parents’ anti-smoking socialization practices (e.g., Chassin et al. 2005; Harakeh et al. 2005; Jackson and Henriksen 1997). Anti-smoking socialization practices reflect specific ways by which parents attempt to prevent smoking onset or smoking maintenance of their children, such as setting smoking-specific rules and giving rewards for not smoking. One important aspect of anti-smoking socialization is the communication about smoking-related issues. Through conversations, parents cannot only explain the house rules (Clark et al. 1999) but also can discuss reasons for not smoking, which is related to a lower risk of adolescent’s smoking (Chassin et al. 1998). Nevertheless, whether conversations are effective or not seems to depend on the quality of the parent–child communication. The quality of communication appears to be a protective factor, which indicates that parents who discuss smoking-related issues in a constructive and respectful manner with their children can prevent adolescents from smoking (Harakeh et al. 2005).

In contrast, some studies showed that the frequency of parental communication about smoking-specific topics was not related to adolescent’s smoking (den Exter Blokland et al. 2006; Ennett et al. 2001). Nevertheless, parental discussions about rules and reprisals seem to predict smoking escalation in youngsters who are already experimenting with smoking (Ennett et al. 2001). In addition, warnings about the harmful consequences of substance use seem to predict continued use for some adolescents who have already initiated use (Andrews et al. 1993). Because a relatively large number of adolescents experiment with smoking or already smoke regularly, the question arises if it is useful that parents talk frequently about smoking during the adolescent years.

At the same time, parents also influence their children through their own smoking. It has been shown that adolescents have a higher risk to start smoking or to continue smoking when one or both parents are smokers (see review by Mayhew et al. 2000). This can be explained by genetic factors (e.g., Brody et al. 2006) and by children modeling parental behaviors (Bandura 1977). However, the question arises how strong these effects of parental smoking are compared to the attempts by which parents actively try to prevent their children from smoking. Perhaps if parents who smoke apply smoking-specific socialization strategies in a successful way, they might simultaneously also diminish the impact of their own smoking. Overall, effective smoking-specific socialization practices seem to be related to lower rates of smoking among adolescents with non-smoking and smoking parents (Clark et al. 1999; den Exter Blokland et al. 2006; Harakeh et al. 2005; Jackson and Henriksen 1997).

Although parents are important socialization agents, peer relationships become increasingly important in the adolescent years, and peer influences are often considered one of the main sources for adolescents’ involvement in smoking (see reviews by Avenevoli and Merikangas 2003; Kobus 2003). Close friends particularly seem to serve as significant (role) models for adolescents: Comparing the impact of close friends and peer groups, it appears that the smoking of the closest friend is more strongly related to onset of smoking in youngsters (Urberg et al. 1997), suggesting that adolescents mainly observe, model, and imitate the smoking behavior of their best friends. However, recent findings suggest that the magnitude of peer influences on risk behaviors might be overestimated, because in many studies the effects of friendship-selection processes were not taken into account (e.g., Jaccard et al. 2005). As previously stated by Kandel (1978), homophily between friends at one point in time is not only the result of socialization processes, but also due to selection processes, which imply that adolescents select their friends on the basis of shared characteristics. It is known that both influence and selection processes contribute to homogeneity in peers with respect to smoking (Engels et al. 1997; Ennett and Bauman 1994; Fisher and Bauman 1988). These findings suggest that adolescents select their friends on the basis of comparable smoking attitudes and behaviors. In combination with reciprocal modeling influences, this process contributes to similarities in smoking behavior between adolescents and their friends.

As argued by Kandel (1996), research on the relative influence of peers and parents on adolescents’ drug use have inflated the importance of peers and underestimated the influence of parents. One of the aspects that should be taken into account when disentangling the relative impact of both social factors is the contribution of parents to children’s peer selection (see also Melby et al. 1993; Rowe et al. 1994). Previous research indicated that parents can function as managers of their offspring’s peer relationships, for example by acting as an advisor and consultant (Ladd and Pettit 2002). During day-to-day conversations parents are able to communicate with their offspring about peer relationships, such as how to initiate friendships, manage conflicts, maintain relationships, deflect teasing, and so on. In this way, parents are able to provide advice or solutions to problems in peer relationships, or listen to their child’s self-generated assessments and solutions. One of the topics that could also be discussed is this respect is substance use. Parents might advise their child about how to deal with peers who let themselves in with substance use, as specific cigarette use. Thus, besides giving anti-smoking messages, parents might express their feelings about smoking peers and advise their adolescent in manners to resist pressure to smoke. Additionally, one might expect that parents affect their child’s affiliation with (non-)smoking peers through these conversations. Parents who discuss smoking-related issues in a constructive and respectful manner might prevent their child not only from smoking but also from affiliating with smoking friends. Presumably, this possible effect of parents on adolescents’ friendships might reflect direct influences of the parental smoking-specific communication, but also indirect influences, by which parents affect peer affiliation through the adolescents’ behavior: Adolescents who do not smoke themselves, are more likely to select friends who also do not smoke. Investigating the impact of parents on adolescents’ friendships is important as previous research showed that imitation plays a major role in smoking (Harakeh et al. 2007) and that the risk for smoking increased dramatically as the number of smoking models in the adolescent’s environment increased (Taylor et al. 2004). When parents are able to prevent their child from affiliating with smoking friends, they take away an important source of smoking modeling and, accordingly, decrease the likelihood that their child will smoke in the future.

The Present Study

The impact of the smoking-specific communication might depend on the smoking status of the parents. Previous research on the effects of parental smoking on adolescents’ friendship-selection processes showed that adolescents with smoking parents are more likely to become affiliated with smoking friends than adolescents with non-smoking parents (Engels et al. 2004). The present study is the first to examine whether parental smoking-specific communication is related to adolescents’ friendship-selection processes, while controlling for parental smoking. Additionally, we investigated whether parental smoking-specific communication and parental smoking is still associated with adolescent’s smoking when the adolescent child is affiliated with the same best friend over a longer period of time.

In this longitudinal study, we investigated whether the quality and frequency of parental smoking-specific communication are related to adolescents’ friendship selection and influence processes, while controlling for possible confounding effects of adolescents’ sex and age (see Avenevoli and Merikangas 2003), and parental smoking. We hypothesized that (1) the quality of parental smoking-specific communication is negatively associated with adolescent’s smoking and best friend’s smoking, (2) the frequency of communication is positively associated with adolescent’s smoking and best friend’s smoking, and that (3) parental smoking is positively associated with adolescent’s smoking and best friend’s smoking. After examining these hypotheses we divided our sample in two groups: one group with adolescents who reported changing friendships during the measurement period, and a second group with adolescents who reported the same best friend at all three measurement moments. Testing our model for the group of adolescents with changing friendships allowed us to investigate our main hypothesis, namely, whether (4) parental smoking-specific communication and parental smoking are related to adolescents’ friendship-selection. The group of adolescents with stable friendships enabled us to explore whether adolescents and their best friends seem to influence each other over time, and what role parental smoking-specific communication and parental smoking play in these processes.

Methods

Procedure

For the present study we used data from the Family and Health project (Harakeh et al. 2005; van der Vorst et al. 2005). For this project the addresses of 5,602 families with at least two children (aged 13–16 years) were obtained from the records of 22 municipalities in the Netherlands. These families were invited by mail to participate in a longitudinal study concerning different socialization processes underlying various health behaviors in adolescence. Of the 981 families who were willing to participate, 216 families did not fulfill the inclusion criteria or could not be contacted due to a lack of information. Because of financial resources, we were restricted to include 428 families in the project. Therefore, we selected this number out of the 765 families, in the way that we obtained (1) approximately equal numbers of possible sibling sex dyads (i.e., boy–boy, boy–girl, girl–boy, girl–girl) and (2) equal numbers of adolescents from lower, middle, and higher educational levels. The latter was important to have variation in educational level in the final sample. Of each family a father, a mother, and two adolescent children participated. Data collection for the first wave (T1) took place between November 2002 and April 2003. Measurements for the second (T2) and third (T3) wave took place 1 and 2 years later, respectively. The families were visited by a trained interviewer. To maintain confidentiality, the interviewers asked the participants to sit apart from each other and not to discuss the questions while completing the questionnaires. A total of 416 families participated at T2 and 404 families participated at T3, resulting in a response rate of 94%. Attrition analyses revealed no differences between the families that participated three times and those that dropped out from the study.

Sample Characteristics

The majority of the participating adolescents were of Dutch origin (>95%). At T1 the age of the older adolescents ranged from 14 to 17 years, with a mean age of 15.2 (SD = .60) years. The age of the younger adolescents ranged from 13 to 15 years, with a mean age of 13.4 (SD = .50) years. There was an almost equal distribution of boys and girls: 52.8% of the older adolescents and 47.7% of the younger adolescents were boys at T1.

Measures

Quality of Communication

Quality of smoking-specific communication was assessed with six items (per parent). The items of this scale reflect a constructive and respectful way of communicating about smoking-related issues (e.g., “My father and I are able to talk easily about our opinions concerning smoking”). Adolescents were asked to report on a 5-point scale which answer applied for them, with responses ranging from 1 = “completely not true” to 5 = “completely true” (Harakeh et al. 2005). The scale scores were averaged. Cronbach’s alphas were .73 for adolescent report about their mother and .81 for adolescents about their fathers.

Frequency of Communication

Frequency of communication was assessed by averaging the scores of eight items referring to how often in the past 12 months parents talked with their child about smoking-related issues (e.g., “During the last 12 months, how many times did your father talk to you about how to resist peer pressure to use tobacco?”) on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “never” to 5 = “very often” (Ennett et al. 2001; see also Harakeh et al. 2005). Cronbach’s alphas were .87 (adolescent report about mother) and .90 (adolescent report about father).

Parental Smoking

To tap parental-smoking status, parents were asked to report on an 8-point scale which stage of smoking applied to them (de Vries et al. 2003). Response categories ranged from 1 = “I have never smoked” to 8 = “I smoke at least once a day”. Each parent was classified into one of the following groups with respect to their lifetime smoking status: never smoker, former smoker, or current smoker. Subsequently, six categories of parental smoking status were established: (1) both parents had never smoked, (2) one parent is a former smoker and the other had never smoked, (3) both parents are former smokers, (4) one parent is a current smoker and the other had never smoked, (5) one parent is a current smoker and the other is a former smoker, or (6) both parents are current smokers (Farkas et al. 1999).

Adolescent’s Smoking

To assess adolescents’ smoking behavior, respondents were asked to report on a 9-point scale which stage of smoking applied to them (de Vries et al. 2003). Responses ranged from 1 = “I never smoked, not even one puff”, to 9 = “I smoke at least once a day”. Because of the skewness of the distribution, this variable was transformed into a new variable ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = “I have never smoked, not even one puff”; 2 = “I tried smoking, I don’t smoke anymore”; 3 = “I stopped smoking, after smoking at least once a month”; 4 = “I smoke occasionally, but not every day”; 5 = “I smoke at least once a day”).

Best Friend’s Smoking

Respondents were asked whether they have a best friend, and if so, to write down the first name and the first letter of the family name of their best friend. Subsequently, they were asked to report on a 9-point scale which stage of smoking applied to their best friend. Responses ranged from 1 = “My best friend never smoked, not even one puff”, to 9 = “My best friend smokes at least once a day”. This variable was transformed into a new variable, similar to what was one for adolescent smoking.

Strategy of Analyses

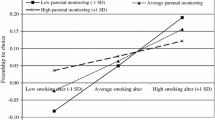

Our analyses proceeded as follows: Descriptive analyses were conducted to provide information about the prevalence of smoking in the sample. Correlations between the model variables were calculated to examine correspondence between mothers’ and fathers’ smoking-specific communication, as well as to examine whether the model variables were associated with each other. To examine whether the quality and frequency of communication and parental smoking were related to adolescent’s smoking and best friend’s smoking, Structural Equation Models were tested with the software package Mplus (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2006). In the proposed model (see Fig. 1), each latent variable was constructed by two reports: adolescents’ reports about their mother and those about their father. In testing the model, we utilized data of the adolescents who participated in all three waves and who reported to have a best friend in all three waves. After excluding the adolescents who did not fulfill these criteria, the sample size used for model testing was n = 305 (older adolescents) and n = 309 (younger adolescents). Subsequently, we applied Missing Value Analyses (MVA) with the EM-algorithm to estimate the remaining missing values in case of optimal utilization of the data. In our dataset only a small number of values were missing (<3%).

Our model was tested on the total group of adolescents (n = 614), which means we combined the sample of the older adolescents with the sample of the younger adolescents to enlarge our statistical power.Footnote 1 Analyses were adjusted for the non-independence of adolescents who were part of the same family. Additionally, we controlled for possible effects of adolescents’ sex and age. Mplus allows to compute standard errors and a chi-square test of model fit taking into account non-independence (complexity) of observations by using the TYPE = COMPLEX procedure in combination with the CLUSTER command (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2006). This procedure clusters the dependent respondents (i.e., adolescents from one family) and then corrects the standard errors of the parameter estimates for dependency leading to unbiased estimates. Because most variables were relatively skewed and the measurement levels of the smoking variables were categorical, the parameters in the model were estimated using the Weighted Least Square with adjusted Mean- and Variance (WLSMV), which is an estimation method specifically developed for ordered categorical dependent variables (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2006). The fit of the model was assessed by the following global fit indices: χ2, CFI (Comparative Fit Index, with a cutoff value of ≥.95), and RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, with a cutoff value of ≤.06) (e.g., Hu and Bentler 1999). Based on these fit indices we were able to test whether the data confirmed the theoretical model.

To disentangle friendship-selection processes from peer influences, we divided the sample into two groups based on whether adolescents had the same best friend across the three waves. The first group existed of adolescents with changing friendships during the three measurements (i.e., adolescents who reported a different friend at different waves) and the second group existed of adolescents with a stable friendship during the three measurements (i.e., adolescents who had the same friend at each wave). The group with changing friendships (n = 425) was utilized to determine whether adolescents select their friends on the basis of their comparable smoking status. Thus, we tested whether associations were found between adolescent’s smoking at T1 and best friend’s smoking at T2, and respectively T2 and T3, and additionally, whether parental smoking-specific communication is associated with adolescent’s smoking and best friend’s smoking. To examine whether best friend’s smoking is associated with adolescent’s smoking over time and vice versa, we tested the model on the group of adolescents with stable friendship (n = 189). In addition, we were able to determine whether parental behaviors are linked to child smoking when the impact of best friend’s smoking was taken into account. Longitudinal associations of parental smoking-specific communication and parental smoking on adolescent and best friend smoking were examined through adding pathways to the model (Fig. 1): We added paths between parental variables at T1 on the one hand, and adolescent’s smoking and best friend’s smoking at T2 on the other.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive findings for the model variables at baseline are presented in Table 1. These findings revealed that according to the adolescents the quality of communication was relatively high, and that parents did not talk very often about smoking-related issues. Supplementary findings concerning adolescent smoking demonstrated that during the measurement period the number of adolescents who never smoked decreased to 46.6% at T3, whereas the number daily smokers increased to 11.9%. For the best friends these percentages were, respectively, 39.7 and 17.8%. Further additional findings showed that in 21.3% of the cases both parents had never smoked, in 28% of the cases one parent was a former smoker and the other had never smoked, in 17.7% of the cases both parents were former smokers, in 10.8% of the cases one parent was a current smoker and the other had never smoked, in 11.7% of the cases one parent was a current smoker and the other was a former smoker, and in 10.5% of the cases both parents were current smokers.

Correlations Between Model Variables

The correlations between adolescent’s reports about their mother and their father for the quality of communication (r = .67, p < .01), as well as for the frequency of communication (r = .79, p < .01), indicated that adolescents experienced similarities in the smoking-specific communication with their mother and their father. Further, the correlation between parental smoking and adolescent smoking (r = .11, p < .01) suggests that adolescent smoking is positively associated with the smoking status of both parents. Correlations between adolescent smoking and best friend smoking were high (T1: r = .62, p < .01; T2: r = .64, p < .01; T3: r = .59, p < .01), indicating similarities in the smoking status of both youngsters (Table 2).

Model Findings

Total Group

To determine whether quality and frequency of parental communication and parental smoking are related to adolescent’s smoking and their best friend’s smoking, we tested a three-wave model (as depicted in Fig. 1). The model showed a relatively good fit to the data, the fit indices were: χ2 (df = 20, n = 614) = 34.74, CFI = 1.00, and RMSEA = .04. The factor loadings of the latent variables in the model were high, with λ = .86 for the adolescents’ report about their mothers and λ = .79 for the adolescents’ report about their fathers on the quality of communication variable, and with λ = .86 for the mothers and λ = .92 for the fathers on the frequency of communication variable. The model explained 75% of adolescent smoking and 61.6% of best friend smoking at T3. Smoking was relatively stable over time, for the adolescents (T1 → T2: β = .80, p < .001; T2 → T3: β = .74, p < .001) as well as for best friends (T1 → T2: β = .50, p < .001; T2 → T3: β = .55, p < .001). Standardized estimates for the cross-lagged paths showed significant associations between adolescent smoking at T1 and best friend smoking at T2 (β = .31, p < .001), and between adolescent smoking at T2 and best friend smoking at T3 (β = .21, p < .001). The association between best friend smoking at T1 and adolescent smoking at T2 was also significant (β = .09, p < .05), which implies a small link between best friend’s smoking and adolescent’s smoking. However, the cross-lagged path from best friend smoking at T2 to adolescent smoking at T3 was not significant. Further, parental smoking showed a small negative association with quality of communication (γ = −.16, p < .01). Parental smoking was not associated with frequency of communication. Quality and frequency of communication were positively associated with each other (β = .18, p < .001). The quality of communication showed a negative association with adolescent smoking at T1 (γ = −.49, p < .001). In contrast to the quality of communication, frequency was found to be positively associated with adolescent smoking (γ = .24, p < .001). Quality and frequency of communication were also associated with best friend smoking (respectively γ = −.37, p < .001 and γ = .20, p < .001). Finally, parental smoking showed no significant association with adolescent smoking, but a positive association with best friend smoking at T1 (γ = .11, p < .05). So, when associations between parental smoking-specific communication and adolescent smoking are taken into consideration, parental smoking was not found related to adolescent smoking (Table 3).

Group of Adolescents with Changing Friendships

To determine whether smoking-specific communication and parental smoking were related to adolescents’ smoking and friendship-selection processes, we tested the theoretical model for the group of adolescents with changing friendships. The model showed a relatively good fit to the data [χ2 (df = 20, n = 425) = 28.22, CFI = 1.00, and RMSEA = .03]. The factor loadings of the latent variables in the model were high, between λ = .80 and λ = .97. Cross-lagged paths showed significant associations between adolescent smoking and best friend smoking at respectively T1 and T2 (β = .40, p < .001), and at T2 and T3 (β = .31, p < .001). These findings indicate that adolescents select their friends on the basis of their comparable smoking behaviors. The quality of parental smoking-specific communication was negatively associated with adolescent smoking at T1 (γ = −.51, p < .001) and best friend smoking at T1 (γ = −.39, p < .001), whereas the frequency of parental smoking-specific communication showed a positive association with adolescent smoking at T1 (γ = .19, p < .001) and best friend smoking at T1 (γ = .15, p < .01). Parental smoking was positively associated with adolescent smoking at T1 (γ = .13, p < .05) and with best friend smoking (γ = .11, p < .05) (Table 3).

To examine longitudinal associations of parental smoking-specific communication and parental smoking on adolescents’ smoking and friendship-selection processes, we added pathways in the model from the smoking-specific communication variables and parental smoking at T1 on the one hand, and adolescent smoking and best friend smoking at T2 on the other. The model showed a good fit to the data [χ2 (df = 17, n = 425) = 18.25, CFI = 1.00, and RMSEA = .01] and explained 74% in adolescent smoking and 57.1% in best friend smoking at T3. The results were similar to those found in the model without these extra paths. However, the associations between frequency of smoking-specific communication and adolescent and best friend smoking at T1 were not significant in this model. Concerning the additional paths, we found a small but significant association between the quality of communication at T1 and adolescent smoking at T2 (γ = −.09, p < .05). The association between the quality of communication at T1 and best friend smoking at T2 was also significant (γ = −.13, p < .05). For the frequency of communication, we found a positive significant association with adolescent smoking at T2 (γ = .11, p < .01) and best friend smoking at T2 (γ = .13, p < .01). For parental smoking, no longitudinal association was found (Table 3).

Group of Adolescents with a Stable Friendship

The model was also tested for the group of adolescents who had a stable friendship, which might give some indication of whether adolescents and their stable best friend seem to influence each other over time, and what role parents play in this process. The model showed a good fit to the data [χ2 (df = 17, n = 189) = 21.9, CFI = 1.00, and RMSEA = .04]. The factor loadings of the latent variables in the model were moderately high, ranging from λ = .71 to λ = .94. Findings of these analyses are comparable with the findings of the total group (Table 3), but with one interesting exception concerning the cross-lagged paths. In contrast with the results for the total model, standardized estimates for the cross-lagged paths demonstrated no significant associations between adolescent smoking at T1 and best friend smoking at T2, and between adolescent smoking at T2 and best friend smoking at T3.

To examine longitudinal associations of parental smoking-specific communication and parental smoking on adolescent’s smoking and best friend’s smoking, we added pathways in the model from the smoking-specific communication variables and parental smoking at T1 on the one hand, and adolescent smoking and best friend smoking at T2 on the other. The model showed a good fit to the data [χ2 (df = 14, n = 189) = 19.36, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA < .05] and explained 77.3% of adolescent smoking and 77.6% of best friend smoking at T3. This analysis enabled us to investigate whether parental smoking-specific communication and parental smoking are related to adolescent smoking, even when the associations between adolescent smoking and best friend smoking were taken into account. The results were similar to those found for the model without these additional pathways, except for the association between best friend smoking at T1 and adolescent smoking at T2, which was no longer significant. Further, no significant associations between the communication variables and parental smoking at T1, and adolescent smoking and best friend smoking at T2 were found.Footnote 2

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the quality and frequency of parental smoking-specific communication and parental smoking are associated with adolescents’ friendship-selection processes. Furthermore, we investigated whether adolescents and their best friends seem to influence each other over time, and what role parental smoking-specific communication and parental smoking play in these processes. The results show that a high quality of parental smoking-specific communication was related to a lower likelihood of adolescent smoking. The frequency of communication was found to be positively associated with adolescent smoking. To investigate the impact of parental smoking-specific communication on adolescents’ friendship-selection processes, we differentiated two groups: one group of adolescents who reported to have the same best friend over a period of two years, thus the group in which no selection processes occurred; and one group of adolescents with changing friendships over this same period. The latter group enabled us to investigate friendship-selection processes. In line with previous findings, we found evidence for friendship selection based on smoking, because adolescent’s smoking affected best friend’s smoking over time (Engels et al. 1997; Ennett and Bauman 1994). Moreover, our results demonstrated direct and indirect associations between the quality and frequency of parental smoking-specific communication and best friend’s smoking, which indicate that parents can affect their child’s friendship-selection processes (see also Brown et al. 1993). Thus, parents seem to be able to affect their child’s friendship-selection processes directly, but also indirectly: When parents succeed in their attempts to prevent their child from smoking, this subsequently will decrease the likelihood that their child will affiliate with smoking friends.

Additionally, the group of adolescents with stable friendships enabled us to examine whether adolescents and their best friends influence each other over time, and whether parents play a role in this. We tested whether parental smoking-specific communication is still related to their child’s smoking, even when their child affiliates with the same friend for a longer period of time. The findings suggest that parents do not appear to directly affect their child’s smoking over a period of one year. It is generally known that during adolescence a transformation of close relationships takes place; as friendships grow closer, the intensity and exclusivity of the parent–child relation decrease (e.g., Laursen and Bukowski 1997). This might explain why adolescents with stable friendships are no longer affected by their parents in terms of smoking. However, that no direct associations were found between parental smoking-specific communication and future adolescent smoking does not necessary imply that parents are not influential. The cross-sectional associations between parenting and adolescent smoking were strong, which might indicate that parents influence their children on the short term. Moreover, adolescents’ smoking behavior is quite stable over time. This could imply that parental smoking-specific communication indirectly affects adolescent smoking one year later, suggesting that when parents prevent their children from smoking during early adolescence, they increase the chance that their children remain non-smokers in the later years.

Smoking parents appear to be less constructive and supportive in their smoking-specific communication than non-smoking parents. This is probably because smoking parents may be more uncertain about their possibilities to prevent their child from smoking, because their advice does not match their actions (e.g., Jackson and Dickinson 2003). Furthermore, longitudinally we found no significant association between parental smoking and adolescent’s smoking when controlling for parental smoking-specific communication. Our interpretation is that what parents express through their smoking-specific communication has more impact on their child’s behavior than the direct effects of parental smoking. However, one should keep in mind that this does not imply that parental smoking does not play a role, because it does affect the quality (and credibility) of parental smoking-specific communication. Prevention programs, therefore, should focus not only on strengthening parents in their ways of communication, but also on smoking cessation among parents.

Findings from our study indicate some directions for future research. When parents do affect their children’s friendship-selection processes through smoking-specific communication, the question arises whether other parental practices affect these selection processes as well. An important aspect of parenting is monitoring and the extent to which parents have knowledge about their children’s behavior, friends, and whereabouts (Stattin and Kerr 2000). It would be interesting to examine whether monitoring and parental knowledge is indirectly related to a lower likelihood of adolescent smoking through the selection of non-smoking friends (see Engels et al. 2005). Mounts (2000) identified several ways parents can deal with adolescents’ peer relationships, including guiding, which is talking about the consequences of being friends with particular people. Another way is prohibiting, which is when parents forbid their child to associate with specific peers. Finally, supporting is a way in which parents encourage their child to undertake activities with peers they like and provide an environment at home where adolescents can have their friends over. It is important to keep in mind that during adolescence parents are challenged to find a balance between autonomy granting and exerting control. Focusing on several peer management skills might lead to an improved understanding of the parental role in adolescents’ friendship selection and could answer the question whether parents should function especially as friendship-formation gatekeepers or whether they should function mainly as advisors or consultants. Additionally, it would be interesting to take the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship into account.

Future research should focus not only on the impact parents have on their children, but also on the effects of the children on their parents. Investigating bidirectional associations between parental practices and adolescent’s behavior allows ascertaining the actual effects of parents on their children, without ignoring the impact children have on their parents. Only a few studies have investigated the bidirectional relationships between parenting and adolescent’s problem behavior, and they clearly support the idea that parents do respond to the problem behavior of their offspring (see Lytton 1990; Stice and Barrera 1995). Recent research has shown that parents also respond to their children’s smoking behavior by increasing smoking-specific conversations (Huver et al. 2007). Finally, one might expect that parents react not only to their child’s behavior, but also to behavior of their child’s best friend: When parents notice that their child is associating with smoking friends they may adjust their parenting practices in order to prevent their child from smoking.

In the current analysis, we examined the quality of smoking-specific communication as a general construct. It would be interesting—and important for prevention—to explore more specific aspects of a highly qualitative parent–child discussion about smoking-related issues. For example, some studies have shown that rigidity in parent–child interactions is linked to externalizing behavioral problems (Hollenstein et al. 2004). Investigating parent–child discussions in an observational setting would allow for analyzing several parent–child communication characteristics, such as flexibility versus rigidity, which subsequently provides more insight into the relation between the parent–child communication and adolescent’s smoking. Another important implication for future research involves the individual characteristics of youngsters. It is plausible that individual differences play an important role in the associations between parental smoking-specific communication and adolescent’s smoking. For example, adolescents who are highly responsive to their parents’ viewpoint might comply with their parents’ advice concerning smoking, while adolescents who are not very responsive to their parents’ viewpoint might neglect their parents’ advice (Jackson 2002).

Another point of interest concerns socialization between adolescents and their best friends. Our findings demonstrated that best friends smoking was marginally related to individual smoking. Although this impact was small, it existed while taking into account the associations between parental smoking and parental smoking-specific communicating, implicating that friend’s smoking contribute to adolescent smoking beyond the impact of parents. Therefore, a next step for future research is to gain more insight into this socialization mechanism. For instance, it might be possible that friends who are older exert a stronger influence on adolescent smoking than a friend who is of the same age or younger. Additionally, sex constellation of the friendship pair might contribute to the strength of the socialization as well, as same-sex friends might exert more influence on each other than different-sex pairs. In short, it is interesting to examine which factors are responsible for the strength of friends’ smoking socialization.

The present study is the first to investigate the relationship between parental smoking-specific communication, smoking of adolescents, and smoking of adolescents’ best friend. Findings provide preliminary evidence that parents are able to affect not only their offspring’s smoking through their smoking-specific communication, but also the peers their child will associate with. However, our pattern of results might not be generalizable to the population as a whole because we used a selective sample of intact families. Therefore, it is necessary to replicate these findings in other samples, such as single-parent families, and specific ethnic groups. Additionally, although we controlled for adolescents’ age in our model, it is plausible that the influence of parents and friends on adolescent smoking might vary during the teenage years. A recent study from Steinberg and Monahan (2007) showed that middle adolescence is an especially significant period for the development of the capacity to resist peer influence. Therefore, it would be interesting to replicate these findings in large samples of different age groups. The fact that we had to combine the data of the younger and older adolescents also limited our ability to investigate whether siblings influence each other with respect to smoking and their selection of (non-)smoking friends (see Melby et al. 1993).

Some other limitations of this study should be addressed. Although we used self-reports of the adolescents and their parents, best friends’ smoking status was based on adolescents’ perceptions. These perceptions might differ from best friend’s actual smoking, as adolescents tend to project their own behavior on their friends (e.g., Bauman and Ennett 1996). However, in a previous study with the same sample as used in the present study, Harakeh et al. (2007) examined whether adolescents were accurate in their reports about their best friend’s smoking. Results of that study indicated a substantial agreement between adolescents’ reports and self-reports of the best friends. Another limitation is that adolescents were asked for information only about their best friend and not for information about other important friends. Therefore, we were not able to examine among the adolescents with changing friendships whether their best friends stay close friends and continued to influence them, or disappeared completely from the adolescent’s immediate environment during the measurement period.

Finally, it is important to stress that we were not able to take genetic influences into account. Recently, scholars have emphasized the importance of encompassing both genetic and social influences in research designs, as this will provide more insight into the specific causes of particular behaviors (e.g., Rutter et al. 1997). For example, it might be possible that adolescents’ friendship-selection processes are influenced by genetic factors as previous research indicated that individuals create their own social environment based on their genetic propensities (e.g., Rose 2007). Thus, adolescents may select friends with a smoking status that fits their own due to specific genetically influenced characteristics, like for example sensation seeking (e.g., Zuckerman 2007). However, there is also evidence that a favorable social environment can dramatically reduce or even eliminate the adverse influence of genetic factors (e.g., Reiss and Neiderhiser 2000; Rose 2007). If parents communicate in a constructive and respectful manner with their offspring, this will create such a favorable environment which then could operate as a protective factor by which possible disadvantageous genetic influences can be suppressed.

In conclusion, the present findings suggest that parental smoking-specific communication affects adolescent’s smoking directly but also indirectly by influencing the friends the adolescents will associate with. Therefore, smoking prevention programs should focus on strengthening parents in the way they communicate about smoking-related issues. Parents who discuss smoking-related issues in a constructive and respectful manner will be more likely to influence their child’s smoking. In addition, parents who communicate in this way might also decrease the likelihood that their child will affiliate with smoking friends.

Notes

We tested the model for the total sample of early and middle adolescents separately to examine possible differences. Results of these analyses showed comparable findings. Unfortunately, due to small sample sizes relative to the number of paths to be estimated, we were not able to test the model for the subsamples of both age groups separately (i.e., the group of adolescents with a stable friendship and the group of adolescents with changing friendships during the measurement period).

The model findings of the separate groups of adolescents (i.e., the group of adolescents with a stable friendship and those with changing friendships) cannot be compared statistically.

References

Andrews, J. A., Hops, H., Ary, D., Tildesley, E., & Harris, J. (1993). Parental influences on early adolescent substance use: Specific and nonspecific effects. Journal of Early Adolescence, 13, 285–310.

Avenevoli, S., & Merikangas, K. R. (2003). Familial influences on adolescent smoking. Addiction, 98(Suppl. 1), 1–20.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Oxford: Prentice-Hall.

Bauman, K. E., & Ennett, S. T. (1996). On the importance of peer influence for adolescent drug use: Commonly neglected considerations. Addiction, 91, 185–198.

Brody, A. L., Mandelkern, M. A., Olmstead, R. E., Scheibal, D., Hahn, E., Shiraga, S., Zamora-Paja, E., Farahi, J., Saxena, S., London, E. D., & McCracken, J. T. (2006). Gene variants of brain dopamine pathways and smoking-induced dopamine release in the ventral caudate/nucleus accumbens. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 808–816.

Brown, B. B., Mounts, N., Lamborn, S. D., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting practices and peer group affiliation in adolescence. Child Development, 64, 467–482.

Chassin, L., Presson, C. C., Rose, J., Sherman, S. J., Davis, M. J., & Gonzalez, J. L. (2005). Parenting style and smoking-specific parenting practices as predictors of adolescent smoking onset. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 30, 333–344.

Chassin, L., Presson, C. C., Todd, M., Rose, J. S., & Sherman, S. J. (1998). Maternal socialization of adolescent smoking: The intergenerational transmission of parenting and smoking. Developmental Psychology, 34, 1189–1201.

Clark, P. I., Scarisbrick-Hauser, A., Gautam, S. P., & Wirk, S. J. (1999). Anti-tobacco socialization in homes of African-American and white parents, and smoking and nonsmoking parents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 24, 329–339.

den Exter Blokland, E. A. W., Hale, W. W., Meeus, W., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2006). Parental anti-smoking socialization: Associations between parental anti-smoking socialization practices and early adolescent smoking initiation. European Addiction Research, 12, 25–32.

de Vries, H., Engels, R. C. M. E., Kremers, S. P. J., Wetzels, J. J. L., & Mudde, A. N. (2003). Parents’ and friends’ smoking status as predictors of smoking onset: findings from six European Countries. Health Education Research, 18, 627–636.

Engels, R. C. M. E., Finkenauer, C., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2005). Illusions of parental control: Parenting and smoking onset in Dutch and Swedish adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35, 1912–1935.

Engels, R. C. M. E., Knibbe, R. A., Drop, M. J., & de Haan, J. T. (1997). Homogeneity of smoking behavior in peer groups: Influence or selection? Health Education & Behavior, 24, 801–811.

Engels, R. C. M. E., Vitaro, F., den Exter Blokland, E., de Kemp, R., & Scholte, R. H. J. (2004). Influence and selection processes in friendships and adolescent smoking behaviour: the role of parental smoking. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 531–544.

Ennett, S. T., & Bauman, K. E. (1994). The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity: The case of adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 653–663.

Ennett, S. T., Bauman, K. E., Foshee, V. A., Pemberton, M., & Hicks, K. A. (2001). Parent-child communication about adolescent tobacco and alcohol use: What do parents say and does it affect youth behavior? Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 48–62.

Farkas, A. J., Distefan, J. M., Choi, W. S., Gilpin, E. A., & Pierce, J. P. (1999). Does parental smoking cessation discourage adolescent smoking? Preventive Medicine, 28, 213–218.

Fisher, L. A., & Bauman, K. E. (1988). Influence and selection in the friend-adolescents relationship: Findings from studies of adolescent smoking and drinking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 18, 289–314.

Harakeh, Z., Engels, R. C. M. E., Van Baaren, R. B., & Scholte, R. H. J. (2007). Imitation of cigarette smoking: An experimental study on smoking in a naturalistic setting. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86, 199–206.

Harakeh, Z., Engels, R. C. M. E., Vermulst, A. A., de Vries, H., & Scholte, R. H. J. (2007). The influence of best friends and siblings on adolescent smoking: A longitudinal study. Psychology & Health, 22, 269–289.

Harakeh, Z., Scholte, R. H. J., de Vries, H., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2005). Parental rules and communication: Their association with adolescent smoking. Addiction, 100, 862–870.

Hollenstein, T., Granic, I., Stoolmiller, M., & Snyder, J. (2004). Rigidity in parent-child interactions and the development of externalizing and internalizing behavior in early childhood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 595–607.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Convential criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Huver, R. M. E., Engels, R. C. M. E., Vermulst, A. A., & de Vries, H. (2007). Bi-directional relations between anti-smoking parenting practices and adolescent smoking. Health Psychology, 26, 762–768.

Jaccard, J., Blanton, H., & Dodge, T. (2005). Peer influences on risk behaviour: An analysis of the effects of a close friend. Developmental Psychology, 41, 135–147.

Jackson, C. (2002). Perceived legitimacy of parental authority and tobacco and alcohol use during early adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 425–432.

Jackson, C., & Dickinson, D. (2003). Can parents who smoke socialise their children against smoking? Results from the smoke-free kids intervention trial. Tobacco Control, 12, 52–59.

Jackson, C., & Henriksen, L. (1997). Do as I say: Parent smoking, antismoking socialization, and smoking onset among children. Addictive Behaviors, 22, 107–114.

Kandel, D. B. (1978). Homophily, selection, and socialization in adolescents friendships. The American Journal of Sociology, 84, 427–436.

Kandel, D. B. (1996). The parental and peer contexts of adolescent deviance: An algebra of interpersonal influences. Journal of Drug Issues, 26, 289–315.

Kobus, K. (2003). Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction, 98(Suppl. 1), 37–55.

Ladd, G. W., & Pettit, G. S. (2002). Parenting and the development of children’s peer relationships. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Practical issues in parenting (pp. 269–309). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associated Publishers.

Laursen, B., & Bukowski, W. M. (1997). A developmental guide to the organization of close relationships. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21, 747–770.

Lytton, H. (1990). Child and parent effects in boys’ conduct disorder: A reinterpretation. Developmental Psychology, 26, 683–697.

Mayhew, K. P., Flay, B. R., & Mott, J. A. (2000). Stages in the development of adolescent smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 59(Suppl. 1), 61–81.

Melby, J. N., Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Lorenz, F. O. (1993). Effects of parental behavior on tobacco use by young male adolescents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 439–454.

Mounts, N. S. (2000). Parental management of adolescent peer relationships: What are its effects on friend selection? In K. Kerns, J. Contreras, & A. Neal-Barnett (Eds.), Family and peers: Linking two social worlds (pp. 167–193). Westport: Praeger.

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2006). Mplus user’s guide. Fourth edition. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Petraitis, J., Flay, B. R., & Miller, T. Q. (1995). Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 67–86.

Reiss, D., & Neiderhiser, J. M. (2000). The interplay of genetic influences and social processes in the developmental theory: Specific mechanism are coming to view. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 357–374.

Rose, R. J. (2007). Peers, parents, and processes of adolescent socialization: A twin-study perspective. In R. C. M. E. Engels, M. Kerr, & H. Stattin (Eds.), Friends, lovers and groups: Key relationships in adolescence (pp. 105–124). Chichester: Wiley.

Rowe, D. C., Woulbroun, E. J., & Gulley, B. L. (1994). Peers and friends as nonshared environmental influences. In R. Plomin, E. M. Hetherington, & D. Reiss (Eds.), Separate social worlds of siblings: The impact of nonshared environment on development (pp. 159–173). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Rutter, M., Dunn, J., Plomin, R., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Maughan, B., Ormel, J., Meyer, J., & Eaves, L. (1997). Integrating nature and nurture: Implications of person-environment correlations and interactions for developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 335–364.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development, 71, 1072–1085.

Steinberg, L., & Monahan, K. C. (2007). Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1531–1543.

Stice, E., & Barrera, M. (1995). A longitudinal examination of the reciprocal relations between perceived parenting and adolescents’ substance use and externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 31, 322–334.

Taylor, J. E., Conard, M. W., Koetting O’Byrne, K., Haddock, C. K., & Poston, W. S. C. (2004). Saturation of tobacco smoking models and risk of alcohol and tobacco use among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 190–196.

Urberg, K. A., Değirmencioğlu, S. M., & Pilgrim, C. (1997). Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Developmental Psychology, 33, 834–844.

van der Vorst, H., Engels, R. C. M. E., Meeus, W., Deković, M., & van Leeuwe, J. (2005). The role of alcohol-specific socialization in adolescents’ drinking behaviour. Addiction, 100, 1464–1476.

World Health Organization. (2007). Tobacco free initiative: Why is tobacco a public health priority? http://www.who.int/tobacco/health_priority/en/index.html. Accessed 13 May 2007.

Zuckerman, M. (2007). Sensation seeking and substance use and abuse: Smoking, drinking, and drugs. In Sensation seeking and risky behavior (pp. 107–143). Washington: American Psychological Association.

Acknowledgements

The Family and Health project was granted by the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF: 2006-3464) and the Dutch Organization of Scientific Research (NWO: 016-005-029; 400-05-051).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Leeuw, R.N.H., Scholte, R.H.J., Harakeh, Z. et al. Parental Smoking-specific Communication, Adolescents’ Smoking Behavior and Friendship Selection. J Youth Adolescence 37, 1229–1241 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9273-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9273-z