Abstract

Objectives

We assess the effects of police use of lethal force on subsequent murders by victim race and armed status before and after the August 2014 death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO.

Methods

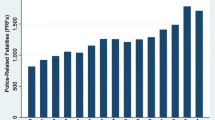

We regress monthly murder levels on instances of police use of lethal force by race and armed status controlling for fixed effects, population, unemployment, and murders in the prior month using city-level data for 93 cities from 2013 to 2015.

Results

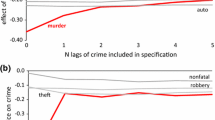

For 2013–2015, we find that a police lethal force incident predicts a 1.8% increase in murders 2 months following the incident. However, prior to Ferguson, a police lethal force incident increases murders by 4.5% (after 2 months) and we are unable to find any evidence of differential responses to police use of lethal force based on victim race. However, we find evidence of differential responses to police use of lethal force based on victim armed status. Post-Ferguson, police use of lethal force is associated with significant differential responses based on victim race. In addition, we see a shift in the aggregate-level response to police use of lethal force. Post-Ferguson, a police lethal force incident decreases the murder level by 3.8% 3 months following the incident. In addition, lethal force incident involving a non-black victim decreases the number of murders by 4.3% while an incident involving a black victim increases the number of murders by 2.1% (after a 2-month lag).

Conclusions

Changes in policing following the events of Ferguson had a generally positive but uneven effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Recent analyses of the determinants of police use of force and racial disparities in the police use of force include: Crow and Adrion (2011), Engel and Calnon (2004), Fryer (2019), Gau et al. (2010), Lawton (2007), Lersch et al. (2008), McCluskey and Terrill (2005), McCluskey et al. (2005), MacDonald et al. (2009), Terrill and Mastrofski (2002), Terrill and Reisig (2003), and Terrill et al. (2008).

Data definitions are available at: https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/aboutthedata.

Each death includes a circumstance code. For instance, there are codes for rape, robbery, burglary, etc. We drop all deaths coded as “felon killed by police.” The set of circumstance codes for the UCR data is available at: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/36393.

For a discussion of finite distributed lags see Wooldridge (2016).

Adding a four-month lag to the model caused collinearity problems.

We use the regional classifications for U.S. states from the U.S. Census Bureau. These classifications are available at: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf.

We include the period from January 2013 to July 2014 as the pre-Ferguson months (52.7% of the total months) and the period from August 2014 to December 2015 as post-Ferguson.

The same basic results hold for the Poisson QMLE estimates when we use population as an offset so that the murder becomes a rate per 100,000 in population. We attach these results in an “Appendix” (Table 6). We change only the dependent variable, the lagged dependent variable, and drop population as a control. All other aspects of the econometric specification remain the same. For the full data set, the estimates show the murder rate rises about 2.0% following an instance of police use of lethal force rather than 1.8% using count data. Pre-Ferguson, the murder rate rises about 6.2% following an instance of police use of lethal force rather than 4.5%. Post-Ferguson, the t − 2 estimate for use of lethal force is − 2.5% rather than − 1.0% and the t − 3 estimate is − 3.0% rather than −3.8%. However, in the murder rate estimates the goodness-of-fit measures fall and the standard errors on the estimates rise relative to the murder level estimates. We see a similar pattern and similar magnitudes in the estimates if we use OLS on the murder rate with the same controls; the standard errors rise again and only the pre-Ferguson t − 2 estimate is significant.

References

Anderson E (1999) Code of the street: decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. W. W. Norton, New York

Berk R, MacDonald J (2008) Overdispersion and Poisson regression. J Quant Criminol 24(3):269–284

Bolger P (2015) Just following orders: a meta-analysis of the correlates of American police officer use of force decisions. Am J Crim Justice 40(3):466–492

Crow M, Adrion B (2011) Focal concerns and police use of force: examining the factors associated with taser use. Police Q 14(4):366–387

Desmond M, Papachristos A, Kirk M (2016) Police violence and citizen crime reporting in the black community. Am Sociol Rev 81(5):857–876

Engel R, Calnon J (2004) Examining the influence of drivers’ characteristics during traffic stops with police: results from a national survey. Justice Q 21(1):49–90

Fryer R (2019) An empirical analysis of racial differences in police use of force. J Polit Econ 127(3):1210–1261

Fyfe J (1982) Blind justice: police shootings in Memphis. J Crim Law Crim 73(2):707–722

Gau J, Mosher C, Pratt T (2010) An inquiry into the impact of suspect race on police use of tasers. Police Q 13(1):27–48

James L, James S, Vila B (2016) The reverse racism effect: are cops more hesitant to shoot black than white suspects? Criminol Public Pol 15(2):457–479

Kirk D, Papachristos A (2011) Cultural mechanisms and the persistence of neighborhood violence. Am J Sociol 116(4):1190–1233

Lawton B (2007) Levels of nonlethal force. J Res Crime Delinq 44(2):163–184

Lersch K, Bazley T, Mieczkowski T, Childs K (2008) Police use of force and neighborhood characteristics: an examination of structural disadvantage, crime, and resistance. Polic Soc 18(3):282–300

MacDonald H (2016) The war on cops: how the new attack on law and order makes everyone less safe. Encounter Books, New York

MacDonald J, Kaminski R, Alpert G, Tennenbaum A (2001) The temporal relationship between killings of civilians and criminal homicide: a refined version of the danger-perception theory. Crime Delinq 47(2):155–172

MacDonald J, Kaminski R, Smith M (2009) The effect of less-lethal weapons on injuries in police use-of-force events. Am J Public Health 99:2268–2274

Maguire E, Nix J, Campbell B (2017) A war on cops? the effects of Ferguson on the number of police officers murdered in the line of duty. Justice Q 34(5):739–758

Mapping Police Violence (2017). http://www.mappingpoliceviolence.org

McCluskey J, Terrill W (2005) Departmental and citizen complaints as predictors of police coercion. Policing 28(3):513–529

McCluskey J, Terrill W, Paoline E (2005) Peer group aggressiveness and the use of coercion in police-suspect encounters. Police Pract Res 6(1):19–37

Morgan S, Pally J (2016) Ferguson, Gray, and Davis: an analysis of recorded crime incidents and arrests in Baltimore City, March 2010 through December 2015. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. http://socweb.soc.jhu.edu/faculty/morgan/reports.html

Nix J, Pickett J (2017) Third-person perceptions, hostile media effects, and policing: developing a theoretical framework for assessing the Ferguson effect. J Crim Justice 51:24–33

Pyrooz D, Decker S, Wolfe S, Shjarback J (2016) Was there a Ferguson effect on crime rates in large U.S. cities? J Crim Justice 46:1–8

Shi L (2009) The limit of oversight in policing: evidence from the 2001 Cincinnati riot. J Public Econ 93(1):99–113

Shjarback J, Pyrooz D, Wolfe S, Decker S (2017) De-policing and crime in the wake of Ferguson: racialized changes in the quantity and quality of policing among Missouri police departments. J Crim Justice 50:42–52

Smith M, Rojek J, Petrocelli M, Withnow B (2017) Measuring disparities in police activities: a state of the art review. Policing 40(2):166–183

Terrill W, Mastrofski S (2002) Situational and officer-based determinants of police coercion. Justice Q 19(2):215–249

Terrill W, Reisig M (2003) Neighborhood context and police use of force. J Res Crime Delinq 40(3):291–321

Terrill W, Leinfelt F, Kwak D (2008) Examining police use of force: a smaller agency perspective. Policing 31(1):57–76

Tyler T, Fagan J (2008) Legitimacy and cooperation: why do people help the police fight crime in their communities? Ohio St J Crim Law 6:231–275

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2017) Local area unemployment statistics. https://www.bls.gov/lau/

U.S. Census Bureau (2017) American fact finder. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml

U.S. Department of Justice (2017) Uniform crime reporting data: supplementary homicide reports, 2013–2015. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/36124. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/36393. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/36790

Williamson V, Trump K, Einstein K (2018) Black lives matter: evidence that police-caused deaths predict protest activity. Perspect Polit 16(2):400–415

Wolfe S, Nix J (2016) The alleged “Ferguson effect” and police willingness to engage in a community partnership. Law Human Behav 40(1):1–10

Wooldridge J (1999) Distribution-free estimation of some nonlinear panel data models. J Econom 90(1):77–97

Wooldridge J (2010) Econometric analysis of cross-section and panel data, 2nd edn. MIT Press, Cambridge

Wooldridge J (2016) Introductory econometrics: a modern approach, 6th edn. Cengage Learning, Boston

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank (without implicating) David Pyrooz, Richard Baker, and Trevor O’Grady for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 6.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vandegrift, D., Connor, B.J. The Effect of Police Use of Lethal Force on Murder Levels in American Cities Before and After Ferguson. J Quant Criminol 36, 235–261 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09429-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09429-6