Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the relationship between criminal offending and mortality over the full life-course of treatment group participants in the Cambridge–Somerville Youth Study (CSYS).

Methods

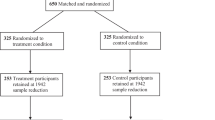

The CSYS is a delinquency prevention experiment and prospective longitudinal survey of the development of offending. Begun in 1939, the study involves 506 at-risk boys, ages 5–13 years (mean birth year = 1928), from Cambridge and Somerville, Massachusetts. Following the analytic strategy of Joan McCord, participants are drawn from the study’s longitudinal arm (N = 253). Data include court convictions of criminal offenses collected during middle age (mean = 47) and death records collected during old age (up to age 89). Death records were collected for 216 participants or 85.4% of the sample.

Results

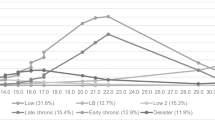

Life-course persistent offenders experience earlier mortality compared to non-offenders (by about 7 years) and adolescent-limited offenders (by about 8 years). While life-course persistent offenders are not more likely to die early (< 40 years) compared to other trajectory groups, they are more likely to experience premature mortality from late middle age into old age. Life-course persistent offenders are also more likely to experience unnatural deaths, with alcoholism confounding the relationship.

Conclusions

That group differences in mortality risk did not emerge until age 55 (while offending is in decline) suggests that the relationship between offending and mortality is not direct and may be spurious. Knowledge about the relationship between criminal offending and mortality can be greatly improved by following participants into old age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As Moffitt (1993: p. 679) writes, “The prognosis for the life-course-persistent person is bleak: Drug and alcohol addiction; unsatisfactory employment; unpaid debts; homelessness; drunk driving; violent assault; multiple and unstable relationships; spouse battery; abandoned, neglected, or abused children; and psychiatric illness have all been reported at very high rates for offenders who persist past the age of 25.” On the other hand, “Unlike their life-course-persistent peers, whose behavior was described as inflexible and refractory to changing circumstances, adolescence-limited delinquents are likely to engage in antisocial behavior in situations where such responses seem profitable to them, but they are also able to abandon antisocial behavior when prosocial styles are more rewarding” (Moffitt 1993: p. 686).

The authors note that the entire sample—both offending and non-offending groups—had “much higher mortality rates than the general [Dutch] population” (van de Weijer et al. 2016: p. 96).

While the authors were quick to point out that the direct and indirect causal perspective could not be ruled out, they also indicated that the timing between (known) offenses and death suggested a spurious relationship.

According to McCord (1984: p. 523), “When a boy was dropped from the treatment program, his matched mate was dropped from the control group.” A comparison of all of the remaining pairs indicated that there were no “reliable differences” between the two groups on a wide range of variables (e.g., age, IQ, referral to the study as “average” or “difficult,” mental health; see also Powers and Witmer 1951: pp. 80–81).

This is consistent with expected age of mortality for the 1930 male birth cohort: 66 (Bell and Miller 2005: p. 98).

As such, there are seven age categories at which convictions were originally recorded: under 18, 18–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44, and 45+.

For adult and juvenile convictions, “serious convictions” are a subset of the “all convictions” measure (i.e., the models do not contain mutually exclusive samples).

As Farrington (2011) notes, the primary family-related risk factors are parental conflict, parental absence, lack of supervision, large families, and young parents.

Hyperactivity is one of the three core symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). While self-control as a personality trait was not measurable with the study data, we note that hyperactivity shares variance with inattention and impulsivity, the two remaining symptoms of ADHD and two of the six core dimensions of low self-control (Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990). Additionally, research has demonstrated that hyperactivity via ADHD is associated with increased criminal behavior (Pratt et al. 2002) predominantly through low self-control (Unnever et al. 2003). We thus consider hyperactivity a proxy for self-control.

The best fit number of groups was first calculated with one zero-order polynomial followed by quadratic polynomials, testing one-group through ten-group solutions. A three-group solution achieved the lowest BIC for both the “all convictions” trajectories (− 601.68) and “felony convictions” trajectories (− 359.71). Second, best fit polynomial groups were estimated for each trajectory, ranging from zero-order (i.e., flat) to cubic. The best fit polynomial group trajectories were zero—linear—quadratic (0, 1, 2) for the “all convictions” model (BIC = − 599.70), and zero—linear–linear (0, 1, 1) for the “felony convictions” model (BIC = − 354.89).

Group-based trajectory modeling was performed using the “traj” command in Stata 15 (see Jones and Nagin 2013).

As acknowledged by Piquero et al. (2014: p. 460), “early death reduces the number of convictions that a man would have received so in a way these relationships are underestimated.” When deaths prior to age 50 were dropped in sensitivity analysis, the relationship between adult felony convictions and age of mortality reached statistical significance (b = − 6.33, p = .001). All other findings in Tables 2 and 3 were generally consistent when early deaths were dropped, however.

Each logistic regression model used the same model specification as the OLS regression shown in Table 2, but control variables are omitted from Table 3 for ease of interpretation. Similar to Table 2, most control variables were not associated with age of mortality. Exceptions are race—black participants were more likely to die by ages 45 (OR 4.42, p = .02), 50 (OR 3.63, p = .03), and 55 (OR 4.42, p = .02) in the all convictions model—and alcoholism—alcoholic participants were more likely to die by ages 60 (OR 1.85, p = .03) and 65 (OR 1.82, p = .04) in the felony convictions model.

Separate logit models were estimated with the adolescent-limited group as reference category. Similar findings emerged. For the all convictions trajectories, life-course persistent offenders were more likely to die by age 45 (OR 4.68), age 55 (OR 4.18), age 65 (OR 2.55), and age 70 (OR 3.67). For the felony convictions trajectories, life-course persistent offenders were more likely to die by age 55 (OR 3.93), age 70 (OR 6.62), and age 75 (OR 8.58). No differences in age of mortality emerged between the adolescent-limited and non-offender groups.

All members of the life-course persistent offender group had died by age 85, and all members of the life-course persistent felony offender group had died by age 80, so death by age 80 is the final category displayed in Table 3.

The control variable for frequent smoker was omitted because no child smokers died due to unnatural causes.

Similar findings emerge when the adolescent-limited group is used as the reference category. After adding controls, life-course persistent offenders are more likely to die by unnatural causes than adolescent-limited offenders for the any convictions trajectories (OR 5.03, p = .02), as well as for felony convictions trajectories (OR 4.47, p = .05). After adding alcoholism, however, this relationship was no longer significant.

Consistent with this viewpoint, our results indicated that hyperactivity was inversely (albeit not significantly) related to age of death.

When unnatural deaths were removed from the analyses, the significant relationship between life-course persistent offending and mortality remained.

This is consistent with earlier research on the full life-course, such as Laub and Vaillant’s (2000: p. 100) finding that among delinquents “only alcohol abuse was significantly related to mortality” and that “[w]hen alcohol abuse was controlled, dysfunctional upbringing, years or education, number of times in jail, and unofficial delinquency made no further contributions toward explaining mortality.”.

Importantly, the state dependence hypothesis could not be fully explored due to lack of information on why most offenders desisted by early adulthood (i.e., adolescent-limited trajectory).

References

Bell FC, Miller ML (2005) Life tables for the United States social security area 1900–2100: Actuarial study, No. 120. Social Security Administration, Washington

Cabot RC (1935) Letter to Miss Gertrude Duffy, June 3, 1935. HUG 4255: Box 97. Richard Clarke Cabot Papers, Pusey Library, Harvard University Archives

Cabot PSdeQ (1940) A long-term study of children: the Cambridge–Somerville Youth Study. Child Dev 11:143–151

Chassin L, Piquero AR, Losoya SH, Mansion AD, Schubert CA (2013) Joint consideration of distal and proximal predictors of premature mortality among serious juvenile offenders. J Adolesc Health 52:689–696

Coffey C, Veit F, Wolfe R, Cini E, Patton GC (2003) Mortality in young offenders: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 326:1064–1066

Daigle MS, Naud H (2012) Risk of dying by suicide inside or outside prison: the shortened lives of male offenders. Can J Criminol Crim Justice 54:511–528

Elonheimo H, Sillanmäki L, Sourander A (2017) Crime and mortality in a population-based nationwide 1981 birth cohort: results from the FinnCrime study. Crim Behav Mental Health 27:15–26

Farrington DP (2011) Families and crime. In: Wilson JQ, Petersilia J (eds) Crime and public policy. Oxford University Press, New York

Farrington DP (2013) Longitudinal and experimental research in criminology. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice 1975–2025. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Farrington DP (2018) Personal communication with the corresponding author, July 2, 2018

Farrington DP, Loeber R, Welsh BC (2010) Longitudinal-experimental studies. In: Piquero AR, Weisburd D (eds) Handbook of quantitative criminology. Springer, New York

Ferriter M, Gedeon T, Buchan S, Findlay S, Mbulawa D, Powney M, Cormac I (2016) Eight decades of mortality in an English high-security hospital. Crim Behav Mental Health 26:403–416

Glueck S, Glueck E (1950) Unraveling juvenile delinquency. Commonwealth Fund, New York

Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (2016) The criminal career perspective as an explanation of crime and a guide to crime control policy: the view from general theories of crime. J Res Crime Delinq 53:406–419

Jones BL, Nagin DS (2013) A note on a Stata plugin for estimating group-based trajectory models. Sociol Methods Res 42:608–613

Kinner SA, Preen DB, Kariminia A, Butler T, Andrews JY, Stoové M, Law M (2011) Counting the cost: estimating the number of deaths among recently released prisoners in Australia. Med J Aust 195:64–68

Lattimore PK, Linster RL, MacDonald JM (1997) Risk of death among serious young offenders. J Res Crime Delinq 34:187–209

Laub JH, Sampson RJ (2003) Shared beginnings, divergent lives: delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Laub JH, Vaillant GE (2000) Delinquency and mortality: a 50-year follow-up study of 1,000 delinquent and nondelinquent boys. Am J Psychiatry 157:96–102

Lindqvist P, Leifman A, Eriksson A (2007) Mortality among homicide offenders: a retrospective population-based long-term follow-up. Crim Behav Mental Health 17:107–112

Loeber R (2012) Does the study of the age-crime curve have a future? In: Loeber R, Welsh BC (eds) The future of criminology. Oxford University Press, New York

McCord J (1978) A thirty-year follow-up of treatment effects. Am Psychol 33:284–289

McCord J (1981) Consideration of some effects of a counseling program. In: Martin SE, Sechrest LB, Redner R (eds) New directions in the rehabilitation of criminal offenders. National Academy Press, Washington

McCord J (1984) A longitudinal study of personality development. In: Mednick SA, Harway M, Finello KM (eds) Handbook of longitudinal research, vol 2. Praeger, New York

McCord J, McCord W (1959a) A follow-up report on the Cambridge–Somerville Youth Study. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 322:89–96

McCord W, McCord J (1959b) Origins of crime: a new evaluation of the Cambridge–Somerville Youth Study. Columbia University Press, New York

Moffitt TE (1993) Adolescent-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 100:674–701

Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Houts R, Poulton R, Roberts BW, Ross S, Sears MR, Thomson WM, Caspi A (2011) A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:2693–2698

Nagin DS (2005) Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Nagin DS (2016) Group-based trajectory modeling and criminal career research. J Res Crime Delinq 53:356–371

Nagin DS, Paternoster R (1991) On the relationship of past and future participants in delinquency. Criminology 29:163–190

Nagin DS, Paternoster R (2000) Population heterogeneity and state dependence: state of the evidence and directions for future research. J Quant Criminol 16:117–144

Patterson E (2013) The dose-response of time served in prison on mortality: New York state, 1989–2003. Am J Public Health 103:523–528

Piquero AR, Farrington DP, Shepherd JP, Auty K (2014) Offending and early death in the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Justice Q 31:445–472

Powers E, Witmer HL (1951) An experiment in the prevention of delinquency: the Cambridge–Somerville Youth Study. Columbia University Press, New York

Pratt TC, Cullen FT, Blevins KR, Leah Daigle L, Unnever JD (2002) The relationship of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder to crime and delinquency: a meta-analysis. Int J Police Sci Manag 4:344–360

Räsänen P, Tiihonen J, Isohanni M, Moring J, Koiranen M (1998) Juvenile mortality, mental disturbances and criminality: a prospective study of the Northern Finland 1966 birth cohort. Acta Psychiatr Scand 97:5–9

Repo-Tiihonen E, Virkkunen M, Tiihonen J (2001) Mortality of antisocial male criminals. J Forensic Psychiatry 12:677–683

Rocque M (2017) Desistance from crime: new advances in theory and research. Palgrave MacMillan, New York

Sailas ES, Feodoroff B, Lindberg NC, Virkkunen ME, Sund R, Wahlbeck K (2006) The mortality of young offenders sentenced to prison and its association with psychiatric disorders: a register study. Eur J Pub Health 16:193–197

Sattar G, Killias M (2005) The death of offenders in Switzerland. Eur J Criminol 2:317–340

Shepherd JP, Shepherd I, Newcombe RG, Farrington DP (2009) Impact of antisocial lifestyle on health: chronic disability and death by middle age. J Public Health 31:506–511

Spaulding AC, Seals RM, McCallum VA, Perez SD, Brzozowski AK, Steenland NK (2011) Prisoner survival inside and outside of the institution: implications for health-care planning. Am J Epidemiol 173:479–487

Stattin H, Romelsjö A (1995) Adult mortality in the light of criminality, substance abuse, and behavioural and family-risk factors in adolescence. Crim Behav Mental Health 5:279–311

Stenbacka M, Jansson B (2014) Unintentional injury mortality–the role of criminal offending. A Swedish longitudinal population based study. Int J Injury Control Saf Promotion 21:127–135

Sullivan CJ (2013) Enhancing translational knowledge on developmental crime prevention: the utility of understanding expert decision making. Criminol Public Policy 12:343–351

Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Mileusnic D (2005) Early violent death among delinquent youth: a prospective longitudinal study. Pediatrics 115:1586–1593

Tikkanen R, Holi M, Lindberg N, Tiihonen J, Virkkunen M (2009) Recidivistic offending and mortality in alcoholic violent offenders: a prospective follow-up study. Psychiatry Res 168:18–25

Tremblay P, Paré P-P (2003) Crime and destiny: patterns in serious offenders’ mortality rates. Can J Criminol Crim Justice 45:299–326

Trumbetta SL, Seltzer BK, Gottesman II, McIntyre KM (2010) Mortality predictors in a 60-year follow-up of adolescent males: exploring delinquency, socioeconomic status, IQ, high-school drop-out status, and personality. Psychosom Med 72:46–52

Unnever JD, Cullen FT, Pratt TC (2003) Parental management, ADHD, and delinquent involvement: reassessing Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory. Justice Q 20:471–500

van de Weijer S, Bijleveld C, Huschek M (2016) Offending and mortality. Adv Life Course Res 28:91–96

van de Weijer S, Smallbone HS, Bouwman V (2018) Parental imprisonment and premature mortality in adulthood. J Dev Life Course Criminol 12:12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-017-0078-1

Welsh BC, Braga AA, Sulivan CJ (2014) Serious youth violence and innovative prevention: on the emerging link between public health and criminology. Justice Q 31:500–523

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the journal editor and the anonymous reviewers for especially helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zane, S.N., Welsh, B.C. & Zimmerman, G.M. Criminal Offending and Mortality over the Full Life-Course: A 70-Year Follow-up of the Cambridge–Somerville Youth Study. J Quant Criminol 35, 691–713 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-018-9399-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-018-9399-4