Abstract

Objective

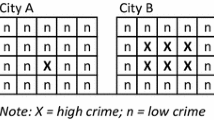

To examine the effect of commuting rates on crime rate estimates in US cities, and to observe potential changes in the effects of other common crime rate correlates after accounting for commuting.

Methods

Crimes evaluated include homicide, aggravated assault, robbery, burglary, larceny, and auto theft. The sample includes US cities with a population of at least 100,000. The analysis first compares crime rankings using a rate based on the residential population and an alternative rate that takes into account daytime population changes due to commuting. Next, multivariate random effects panel models are used to evaluate the effect of commuting on crime rates, and to examine the extent to which the effects of other predictors change after controlling for commuting.

Results

A city’s ranking can vary considerably depending on which denominator is used. Multivariate findings suggest that daily commuting rates are a significant, strong predictor of crime rates, and that controlling for commuting yields important changes in the effects of concentrated disadvantage, concentrated affluence, racial composition and residential instability.

Conclusions

The impact of the commuting population on crime rate rankings underscores the importance of viewing crime rankings with great caution. Specifically, the residential crime rate overestimates relative risk for cities that attract a large daily population from outside the city limits. Findings provide support for the routine activities perspective, and suggest that future research examining city-level crime rates should control for commuting. Limitations to the study and directions for future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Homicide rates are expressed per 1 million persons to make the coefficients more readable.

Skewness and kurtosis were 0.77 and 4.04, respectively, using Stata’s “summarize” command which centers skewness and kurtosis on values of 0 and 3. No severe outliers were found for this variable using Stata’s “iqr” command.

In the 1990 and 2000 decennial censuses, respondents were asked whether they lived in a different house 5 years ago, while the 2009–11 ACS asked about one year ago. To make the measures more comparable, the percentage measures for 1990 and 2000 were divided by five to generate estimates of the percentage of people who moved in the past year.

Prior research has often included black percentage as one of the components in a concentrated disadvantage index (Sampson et al. 1997; Steffensmeier and Haynie 2000). However, because racial composition has been an important factor in both the theoretical and empirical literature, percent black is included separately in the current study. Percent black and the concentrated disadvantage factor score were only moderately correlated (no more than r = 0.61). All VIFs were less than 4 in each year, with average VIFs of around 2.5, and a condition number <30 in each year.

Prior research on auto theft suggests that opportunity, in the form of more vehicles available to steal, may be particularly relevant for explaining variation in offense rates (Copes 1999). In supplementary auto theft models (not shown), the inclusion of a measure of vehicles per square mile did not yield substantive changes to the results. In order to maintain model comparability across crime types, this variable is not included in the reported models.

Hausman tests were significant for robbery, burglary, and larceny. However, the relatively small number of cases, and the relatively low within-unit variation in the key predictor—the commuting rate—relative to the dependent variables, lead to a preference for random effects models for all crime types. A “hybrid” random effects model was also estimated for each crime type to decompose the predictors into their between- and within-unit components, and the coefficients for both components were highly consistent for all predictors (Allison 2005; Gaspera et al. 2010; Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). As this type of model complicates the mediational analysis, again, the simpler random effects model was chosen.

Three tests were used to evaluate the confounding effect of the commuting population via the 'sgmediation' command (adapted by the authors to accommodate panel models) in Stata 12.1—the Sobel first-order solution, the Arolian second-order exact solution, and the Goodman unbiased solution (Baron and Kenney 1986; MacKinnon et al. 2002). These tests are commonly used to evaluate mediation, but they are also appropriate for evaluating confounding effects since there is no statistical difference between mediation and confounding. The statistic suggested by Paternoster et al. (1998), for testing the equality of coefficients across models is widely used in criminology, but it is designed to test coefficients across independent samples, which is not the case when evaluating mediating or confounding effects.

References

Allison PD (2005) Fixed effects regression methods for longitudinal data using SAS. SAS Institute, Cary

Baron RM, Kenney DA (1986) The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers 51:1173–1182

Blumestein A, Cohen J, Rosenfeld R (1991) Trend and deviation in crime rates: a comparison of UCR and NCS data for burglary and robbery. Criminology 29:237–263

Boggs SL (1965) Urban crime patterns. Am Sociol Rev 30:899–908

Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Kato P, Sealand N (1993) Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent behavior? Am J Sociol 99:353–395

Chamlin MB, Cochran JK (1996) Macro social measures of crime: toward the selection of an appropriate deflator. J Crime Justice 14:121–144

Cohen LE, Felson M (1979) Social change and crime rate trends: a routine activity approach. Am Sociol Rev 44:588–608

Cohen LE, Kaufman RL, Gottfredson MR (1985) Risk-based crime statistics: a forecasting comparison for burglary and auto theft. J Crime Justice 13:445–457

Copes H (1999) Routine activities and motor vehicle theft: a crime specific approach. J of Crime and Justice 22:125–146

Decker S (1983) Comparing victimization and official estimates of crime: a re-examination of the validity of police statistics. Am J Police 2:193–201

Farley JE (1987) Suburbanization and central-city crime rates: new evidence and a reinterpretation. Am J Sociol 93:688–700

Farley JE, Hansel M (1981) The ecological context of urban crime: a further exploration. Urban Aff Rev 17:37–54

Federal Bureau of Investigation (2002) Uniform crime reporting program: offenses known and clearances by arrest, 2000 [data file]. http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/ICPSR/STUDY/03447.xml

Federal Bureau of Investigation (2009) Uniform Crime Reporting Program Data [United States]: 1975–1997 9 [data file]. http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/ICPSR/STUDY/09028.xml

Federal Bureau of Investigation (2012) Uniform crime reporting program: offenses known and clearances by arrest, 2010 [data file]. http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/cocoon/ICPSR/STUDY/33526.xml

Gaspera J, DeLucaa S, Estacion A (2010) Coming and going: explaining the effects of residential and school mobility on adolescent delinquency. Soc Sci Res 39:459–476

Gibbs JP, Erickson ML (1976) Crime rates of American cities in an ecological context. Am J Sociol 82:605–620

Gove WR, Hughes M, Geerken M (1985) Are uniform crime reports a valid indicator of the index crimes? An affirmative answer with minor qualifications. Criminology 23:451–502

Kitsuse JI, Cicourel AV (1963) A note on the uses of official statistics. Soc Probl 11:131–139

Krivo LJ, Peterson RD (2000) The structural context of homicide: accounting for racial differences in process. Am Sociol Rev 65:547–559

Land KC, McCall PL, Cohen LE (1990) Structural covariates of homicide rates: are there any invariances across time and social space? Am J Sociol 95:922

Liska AE, Chamlin MB, Reed MD (1985) Testing the economic production and conflict models of crime control. Soc Forces 64:119–138

Loftin C, McDowall D, Fetzer MD (2008) A comparison of SHR and vital statistics homicide estimates for US cities. J Contemp Crime Justice 24:4–17

MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V (2002) A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods 7:83–104

McDowall D, Loftin C (2009) Do US city crime rates follow a national trend? The influence of nationwide conditions on local crime patterns. J Quant Criminol 25:307–324

Messner SM, Blau JR (1987) Routine liesure activities and rates of crime: a macro-level analysis. Soc Forces 65:1035–1052

Miethe TD, Stafford MC, Long JS (1987) Social differentiation in criminal victimization: a test of routine activities/lifestyle. Am Sociol Rev 52:184–194

Miethe TD, Hughes M, McDowall D (1991) Social change and crime rates: an evaluation of alternative theoretical approaches. Soc Forces 70:165–185

O’Brien RM (1985) Crime and victimization data. Sage, Beverly Hills

O’Brien RM, Shichor D, Decker DL (1980) An empirical comparison of the validity of UCR and NCS crime rates. Sociol Quart 21:391–401

Ousey GC (1999) Homicide, structural factors, and the racial invariance assumption. Criminology 37:405–426

Paternoster R, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A (1998) Using the correct statistical test for the equality of coefficients. Criminology 36:859–866

Pettiway LE (1985) The internal structure of the ghetto and the criminal commute. J Black Stud 16:189–211

Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Reiss AJ (1967) Measurement of the nature and amount of crime, field surveys iii, studies in crime and law enforcement in major metropolitan areas, President’s common on law enforcement and administration of justice. United States Government Printing Office, Washington

Reschovsky C (2004) Journey to Work: 2000. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistical Administration, US Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/prod/2004pubs/c2kbr-33.pdf

Sampson RJ (1987) Urban black violence: the effect of male joblessness and family disruption. Am J Sociol 93:348–382

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277:918–924

Sellin T, Wolfgang ME (1964) The measurement of delinquency. Wiley, New York

Shihadeh ES, Ousey GC (1996) Metropolitan expansion and black social dislocation the link between suburbanization and center-city crime. Soc Forces 75:649–666

Shihadeh ES, Steffensmeier DJ (1994) Economic inequality, family disruption, and urban black violence: cities as units of stratification and social control. Soc Forces 73:729–751

Skogan WG (1974) The validity of official crime statistics: an empirical investigation. Soc Sci Quart 55:25–38

Stafford MS, Gibbs JP (1980) Crime rates in an ecological context: extension of a proposition. Soc Sci Quart 61:653–665

Steffensmeier DJ, Haynie D (2000) Gender, structural disadvantage, and urban crime: do macrosocial variables also explain female offending rates? Criminology 38:403–438

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stults, B.J., Hasbrouck, M. The Effect of Commuting on City-Level Crime Rates. J Quant Criminol 31, 331–350 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9251-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9251-z