Abstract

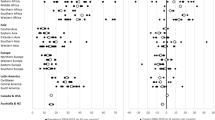

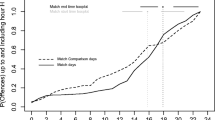

Recent research has demonstrated that individual crimes elevate the risk for subsequent crimes nearby, a phenomenon termed “near-repeats.” Yet these assessments only reveal global patterns of event interdependence, ignoring the possibility that individual events may be part of localized bursts of activity, or microcycles. In this study, we propose a method for identifying and analyzing criminal microcycles; groups of events that are proximate to each other in both space and time. We use the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) to analyze over 4,000 terrorist attacks attributed to the FMLN in El Salvador and the ETA in Spain; two terrorist organizations that were both extremely active and violent but differed greatly in terms of history, grievances and motives. Based on the definition developed, we find strong support for the conclusion that many of the terrorist attacks attributed to these two distinctive groups were part of violent microcycles and that the spatio-temporal attack patterns of these two groups exhibit substantial similarities. Our logistic regression analysis shows that for both ETA and the FMLN, compared to other tactics used by terrorists, bombings and non-lethal attacks are more likely to be part of microcycles and that compared to attacks which occur elsewhere, attacks aimed at national or provincial capitals or areas of specific strategic interest to the terrorist organization are more likely to be part of microcycles. Finally, for the FMLN only, compared to other attacks, those on military and government targets were more likely part of microcycles. We argue that these methods could be useful more generally for understanding the situational and temporal distribution of crime.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We regard our focus on terrorism as a logical extension in that much research (e.g., Wilkinson 1986; Hoffman 1998; Pape 2005; Dugan et al. 2005; Kydd and Walter 2006; Enders and Sandler 2006; Clarke and Newman 2006) suggests that terrorism is even more likely than more ordinary crime to be carefully planned. Thus, Crenshaw (1998: 7) characterizes terrorist violence as “an expression of political strategy” and claims that it represents “a willful choice made by an organization for political and strategic reasons.” And Sandler and Arce (2003: 320) point out that the predictable responses of terrorist groups to changes in sanctions and rewards aimed at constraining their behavior is strong evidence for advanced planning.

According to Sanchez-Cuenca (2009: 3), Basque nationalism is strongest in Vizcaya, Guipuzcoa and the north of Navarra and is much weaker in the three French provinces, in the South of Navarra and in Alava.

These categories are mutually exclusive. For example, we categorize assassinations that use explosives as “assassinations” while “bombings” refer to the more indiscriminate use of explosives in markets, police stations, and other public places.

Data from 1993 were lost by PGIS in an office move and we have never been able to successfully restore them. We, therefore, treat 1993 as missing.

Another difference between the GTD and other datasets of terrorist activity is the inclusion of attacks against the military and police, actions that are sometimes classified in other open source data bases as insurgent actions and distinct from terrorist attacks. While theoretical differences regarding strategies of insurgency compared to terrorism exist, broad criteria for inclusion here allows us to examine a wide range of violent group behavior by these two organizations.

For example, if a source said only that “a group of armed members of FMLN stormed a village in the Chalatenango department, approximately 60 km from San Salvador,” we could not infer an exact latitude and longitude of the location. However, in such cases we did collect information on the department (or 1st administrative subdivision) and where applicable, the municipality (2nd administrative subdivision).

Because attacks geocoded to the same centroid of a city may in actuality have occurred in different parts of the same city, it is more accurate to refer to these patterns as “near-repeat victimizations.”

A majority of those missing geo-coordinates were attacks within the Basque Country where the specific village location was not provided in the original source.

While others have noted that analyses using geocoded data with less than 85% non-missing data may produce unstable results (Ratcliffe 2004), the impact of missing data on our analysis is likely to be conservative because the majority of these events would likely have increased, rather than decreased, the number of near-repeats and microcycles observed. For example, in El Salvador, 422 of the 699 attacks with no latitude or longitude (60.4%) were terrorist strikes against power poles or other electrical infrastructure in rural areas—often occurring on the same day. Thus, if specific geocoded information on these cases had been available, these repeated coordinated attacks against electrical infrastructure would have resulted in a larger number of cases falling into microcycles.

Sanchez-Cuenca (2009: 613) reports only three ETA-related casualties between 1968 and 1970, the year when our analysis begins.

On the eve of Franco’s death in 1975, ETA split into two organizations, the political-military ETA (ETApm) and the military ETA (ETAm). ETApm, the larger and more powerful of the two, favored political participation and in 1981, renounced the use of terrorism and began full participation in electoral politics. While the analysis included ETApm, ETAm, and other ETA affiliates (Iraultza, Grupo Vasco Iraultza, Iraultza Aske), most of the attacks and fatalities attributed to ETA in our data base were actually carried out by ETAm (LaFree et al. 2011).

Including the ETA cases, GTD recorded a total of 2,958 terrorist attacks against Spain during the study period. Other major groups responsible for these attacks included the First of October Antifascist Resistance Group (or GRAPO; 207 attacks; 7%); Terra Lliure (or TL; 61 attacks; 2.0%); and the Revolutionary Anti-Fascist Patriotic Front (or FRAP; 47 attacks; 1.6%).

Those groups include: Fuerzas Populares de Liberación (FPL), Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación (FAL), Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP), Fuerzas Armadas de la Resistencia Nacional (RN-FARN), and the Ejército Revolucionario de los Trabajadores Centroamericanos (ERTC). A variety of youth organizations were also merged into the FMLN at the same time.

In results not presented here, we did include the additional attacks by these leftist groups and found few substantive differences with the results presented (analyses available on request).

We selected these areas for El Salvador because they served as critical locations for training facilities, staging operations and popular support for the FMLN (Wood 2003). By the end of the Salvadoran Civil War, the FMLN occupied a significant portion of both Usulután and Chalatenango departments (25.3 and 17%, respectively). Usulután was also the site of extensive agricultural reforms that were integral to the grievances of the FMLN and played a strategic role for the FMLN commanders. Morazán was also a strategic resource base for the FMLN throughout the conflict.

Statistical significance for the test result (Z) is determined through a Monte Carlo simulation approach using random permutations of the temporal distance matrix, recalculating a test result after each permutation. A set of 999 permutations are performed, generating a probability distribution for Z under the assumption that the space–time matching is random.

Given the comparatively low occurrence rates of terrorism, we use two as a minimum number of linked events.

We conducted several additional analyses to test the robustness of these results by grouping all attacks from a more generic movement in each country (Basque Resistance and Salvadoran Left), as well as all attacks from both generic movements and those with unknown group attributions. The results from those analyses did not produce substantial differences in substantive results and are available from the authors upon request.

The pattern of significant results at 50 miles from an attack by FMLN is likely in large part a condition of the size of the country. El Salvador is a small, densely populated country covering an area the size of Massachusetts (~8,100 square miles) and roughly 170 miles from East to West: a 50-mile boundary covers nearly one-third of the country.

In general, increasing the critical spatial distance for including attacks within microcycles should allow more nearby events to be included in each burst, resulting in longer cycles that account for more of the total events within that specific perpetrator categorization. For attacks by the FMLN, moving from a critical distance of 5 miles to 10 miles actually produced cycles that were longer (by almost three days on average), yet these longer cycles did not have substantially more events within them than those created by the smaller critical distances (13.3 events/cycle compared with 12.5 events/cycle, respectively).

In results not presented here, we also ran the same regression models for microcycles constructed at 2 weeks and 10 miles and found no substantive differences (results available on request).

It is substantively important to make between-group comparisons in these analyses among organizations and countries. However, as noted by Allison (1999) in limited dependent variable regression, differences in the degree of unobserved heterogeneity in the disturbance term can produce cross-group comparisons that are incorrect. To correct for this possibility, Allison (1999) suggests employing models that allow for interaction effects to be calculated and do not assume equality of heterogeneity in the error terms of the groups that are being compared. However, Williams (2009) suggests a method that does not require that an additional parameter be added to the model and is not limited by the assumption that at least one estimate is the same in the populations being compared. In general, it is preferable to use the heterogeneous choice model to better understand the potential impacts of differences in the error variance without the more restrictive assumptions of unrestricted interactions. Following this reasoning, we estimated heterogeneous choice models on a combined dataset of ETA and FMLN events using group membership (FMLN = 1) as a determinant of the residual variation. While residual variation is present between groups in microcycle inclusion, the difference is not statistically significant once interactions between group membership and each predictor are included. Overall, the results differ little from the standard use of z-scores to identify statistically significant differences, so we have decided to present results from the logistic regression analysis, which will be more familiar to readers. However, the alternative results are available from the authors on request.

References

Alexander Y, Pluchinsky D (eds) (1992) Europe’s last red terrorists: the fighting communist organizations. Frank Cass Publishers, Washington, DC

Allison P (1999) Comparing logit and probit coefficients across groups. Soc Meth Res 28:186–208

Bapat NA (2007) The internationalization of terrorist campaigns. Conf Manage Peace Sci 24:265–280

Barabasi AL (2005) The origin of bursts and heavy tails in humans dynamics. Nature 435:207–211

Benmelech E, Berrebi C, Klor EF (2010) Economic conditions and the quality of suicide terrorism. C.E.P.R. Discussion papers

Bernasco W (2008) Them again? Same-offender involvement in repeat and near repeat burglaries. Eur J Crim 5:411–431

Berrebi C, Lakdawalla D (2007) How does terrorism risk vary across space and time? An analysis based on the Israeli experience. Def Peace Econ 18:113–191

Bohorquez JC, Gourley S, Dixon AR, Spagat M, Johnson NF (2009) Common ecology quantified human insurgency. Nature 462:911–914

Bracamonte JAM, Spencer DE (1995) Strategy and tactics of Salvadoran FMLN guerrillas: last battle of the cold war, blueprint for future conflicts. Praeger, CT

Braga AA (2001) The effects of hot spots policing on crime. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 578:104–125

Braga AA, Bond B (2008) Policing crime and disorder hot spots: a randomized controlled trial. Criminology 46:577–607

Braga AA, Papachristos AV, Hureau DM (2010) The concentration and stability of gun violence at micro places in Boston, 1980–2008. J Quant Crim 26:33–53

Burke R (2006) Counter-terrorism for emergency responders. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Chainey S, Tompson L, Uhlig S (2008) The utility of hotspot mapping for predicting spatial patterns of crime. Secur J 21:4–28

Clarke RV, Newman GR (2006) Outsmarting the terrorists. Praeger, New York

Cohen A (1983) Comparing regression coefficients across subsamples: a study of the statistical test. Soc Meth Res 12:77–94

Crenshaw M (1998) The logic of terrorism: terrorist behavior as a product of choice. Terr Counter Terr 2:54–64

Dugan L (2010) The series hazard model: an alternative to time series for event data. J Quant Crim. doi:10.1007/s10940-010-9127-1. Accessed 1/5/2011

Dugan L, LaFree G, Piquero AR (2005) Testing a rational choice model of airline hijackings. Criminology 43:1031–1066

Enders W, Sandler T (2006) The political economy of terrorism. Cambridge University Press, New York

Farrell G, Pease K (eds) (2001) Repeat victimization. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey

Friestad DE (1978) Descriptive analysis of terrorist targets in a crime prevention through environmental design context. Unpublished dissertation, Florida State University

Goh KI, Barabasi AL (2008) Burstiness and memory in complex systems. Europhysics Lett 48002:p1–p5

Goodwin J (2006) A theory of categorical terrorism. Soc Forces 84:2027–2046

Grenier Y (1999) The emergence of insurgency in El Salvador: ideology and political will. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh

Groff ER, Weisburd D, Yang SM (2010) Is it important to examine crime at a local “micro” level? A longitudinal analysis of street to street variability in crime trajectories. J Quant Crim 26:7–32

Grubesic TH, Mack EA (2008) Spatio-temporal interaction of urban crime. J Quant Crim 24:285–306

Harries KD (1981) Alternative denominators in conventional crime rates. In: Brantingham PJ, Brantingham PL (eds) Environmental criminology. Sage, London, pp 147–165

Hipp JR (2007) Block, tract and levels of aggregation: neighborhood structure and crime and disorder as a case in point. Am Soc Rev 72:659–680

Hoffman B (1998) Inside terrorism. Columbia Univ Press, New York

Johnson SD, Braithwaite A (2009) Spatio-temporal modeling of insurgency in Iraq. In: Freilich JD, Newman GR (eds) Reducing terrorism through situational crime prevention. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, pp 9–32

Johnson SD, Bowers KJ, Hirschfield AFG (1997) New insights into the spatial and temporal distribution of repeat victimization. Br J Criminol 37:224–241

Johnson SD, Bernasco W, Bowers KJ, Elffers H, Ratcliffe J, Rengert G, Townsley M (2007) Space-time patterns of risk: a cross national assessment of residential burglary victimization. J Quant Criminol 23:201–219

Johnson SD, Summers L, Pease K (2009) Offender as forager? A direct test of the boost account of victimization. J Quant Crim 25:181–200

Kalyvas SN (2006) The logic of violence in civil war. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kalyvas SN (2008) Promises and pitfalls of an emerging research program: The microdynamics of civil war. In: Kalyvas SN, Shapiro I, Masoud T (eds) Order, conflict, and violence. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 397–421

Kennedy LW, Caplan JM, Piza E (forthcoming) Risk clusters, hotspots, and spatial intelligence: risk terrain modeling as an algorithm for police resource allocation strategies. J Quant Crim. doi:10.1007/s10940-010-9126-2

Knox G (1964) Epidemiology of childhood leukemia in Northumberland and Durham. Br J Prev Soc Med 18:17–24

Krueger AB, Laitin DD (2008) Kto kogo? A cross-country study of the origins and targets of terrorism. In: Keefer P, Loayza N (eds) Terrorism, economic development, and political openness. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 148–173

Kydd AH, Walter BF (2006) The strategies of terrorism. Int Secur 31:49–80

LaFree G (forthcoming) Generating terrorism event databases: results from the Global Terrorism Database, 1970 to 2008. In: Lum C, Kennedy L (eds) Evidence-based counter terrorism. Springer, New York

LaFree G, Dugan L (2007) Introducing the global terrorism database. Polit Viol Terror 19:181–204

LaFree G, Dugan L (2009) Research on terrorism and countering terrorism. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 38. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 413–477

LaFree G, Dugan L (forthcoming) Trends in global terrorism, 1970–2008. In: Hewitt JJ, Wilkenfeld J, Gurr TR (eds) Peace and conflict: 2012. Paradigm Publishers, Boulder

LaFree G, Dugan L, Korte R (2009) The impact of British counterterrorist strategies on political violence in Northern Ireland: comparing deterrence and backlash models. Criminology 47:17–45

LaFree G, Dugan L, Xie M, Singh P (2011) Spatial and temporal patterns of terrorist attacks by ETA 1970 to 2007. J Quant Criminol. doi:10.1007/s10940-011-9133-y.

Li Q (2005) Does democracy promote or reduce transnational terrorist incidents? J Conf Resol 49:278–297

Lohman AD, Flint C (2010) The geography of insurgency. Geog Compass 4:1154–1166

Lyall J (2009) Does indiscriminate violence incite insurgent attacks? Evidence from Chechnya. J Conf Resol 53:331–362

Madsen RE, Kauchak D, Elkan C (2005) Modeling word burstiness using the Dirichlet distribution. In: Proceedings of the 22nd international conference on machine learning

McClintock C (1998) Revolutionary movements in Latin America. US Institute of Peace Press, Washington, DC

Murshed M, Gates S (2005) Spatial-horizontal inequality and the Maoist insurgency in Nepal. Rev Dev Econ 9:121–134

Nagin DS, Land KC (1993) Age, criminal careers, and population heterogeneity: specification and estimation of a nonparametic, mixed Poisson model. Criminology 31:327–362

North BV, Curtis D, Sham PC (2002) A note on the calculation of empirical p values from Monte Carlo procedures. Am J Hum Gen 71:439–441

Pape RA (2003) The strategic logic of suicide terrorism. Am Pol Sci Rev 97:1–19

Pape RA (2005) Dying to win. Random House, New York

Paternoster R, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Piquero A (1998) Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology 36:859–866

Pease K (1998) Repeat victimization: taking stock. Crime detection and prevention series, paper 90. Home Office, London

Polvi N, Looman T, Humphries C, Pease K (1991) The time course of repeat burglary victimization. Br J Criminol 31:411–414

Quetelet A (1984) Research on the propensity for crime at different ages (first edition 1831; translated by Sylvester, S). Anderson, Cincinnati

Rapoport DC (1971) Assassination and terrorism. CBC Merchandising, Toronto

Ratcliffe JH (2004) Geocoding crime and a first estimate of a minimum acceptable hit rate. Int J Geogl Info Sci 18:61–72

Ratcliffe JH, Rengert GF (2008) Near-repeat patterns in Philadelphia shootings. Secur J 21:58–76

Reinares F (2004) Who are the terrorists? Analyzing changes in sociological profile among members of ETA. Stud Conf Terror 27:465–488

Sanchez-Cuenca I (2009) The persistence of nationalist terrorism: the case of ETA. In: Mulaj K (ed) Violent non-state actors in contemporary world politics. Columbia University Press, New York

Sandler T, Arce MDG (2003) Terrorism and game theory. Sim Gaming 34:319–337

Savitch HV (2007) Cities in a time of terror: space, territory and local resilience. ME Sharpe, Armonk

Shaw CR (1929) Delinquency areas. Univ. of Chicago Press, Oxford

Shellman SM (2008) Coding disaggregated intrastate conflict: machine processing the behavior of substate actors over time and space. Polit Anal 16:464–477

Sherman L (1995) Hot spots of crime and criminal career of places. In: Eck JE, Weisburd DM (eds) Crime and place: crime prevention studies, vol 4. Police Executive Research Forum, Washington, DC, pp 35–52

Sherman L, Weisburd D (1995) General deterrent effects of police patrol in crime ‘hot spots’: a randomized, controlled trial. Just Q 12:625–648

Sherman L, Gartin P, Buerger M (1989) Hot spots of predatory crime: routine activities and the criminology of place. Criminology 27:27–55

Short MB, D’Orsogna MR, Brantingham J, Tita GE (2009) Measuring and modeling repeat and near-repeat burglary effects. J Quant Criminol 25:325–339

Siebeneck LK, Medina RM, Yamada I, Hepner GF (2009) Spatial and temporal analyses of terrorist incidents in Iraq, 2004–2006. Stud Conf Terror 32:591–610

Siqueira K, Sandler T (2007) Terrorism backlash, terrorism mitigation, and policy delegation. J Pub Econ 91:1800–1815

Smith PD, Rose TA (2006) Blast wave propagation in city streets—an overview. Prog Struct Eng Ma 8:16–28

Smith BL, Cothren J, Roberts P, Damphousse KR (2008) Geospatial analysis of terrorist activities. National Institute of Justice Final Report. Department of Justice, Washington, DC

Suttles GD (1972) The social construction of communities. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Townsley M (2007) Near repeat burglary chains: describing the physical and network properties of a network of close burglary pairs. Presented at the Crime Hot Spots: behavioral, computation, and mathematical models symposium, 01/31/2007

Townsley M, Johnson SD, Ratcliffe JH (2008) Space-time dynamics of insurgent activity in Iraq. Security J 21:139–146

Vasquez A (2005) Exact results for the Barabási Model of human dynamics. Phys Rev Lett 95:248701

Vasquez A, Oliveira JG, Deszo Z, Goh KI, Kondor I, Barabasi AL (2006) Modeling bursts and heavy tails in human dynamics. Phys Rev E 73:036127

Wilkinson P (1986) Terrorism and the liberal state, 2nd edn. New York University Press, New York

Williams R (2009) Using heterogeneous choice models to compare logit and probit coefficients across groups. Soc Meth Res 37:531–559

Wilson MA, Scholes A, Brocklehurst E (2010) A behavioural analysis of terrorist action: the assassination and bombing campaigns of ETA between 1980 and 2007. Brit J Crim 50:690–707

Wood EJ (2003) Rebel collective action and civil war in El Salvador. Cambridge University Press, New York

Yang SM (2010) Assessing the spatio-temporal relationship between disorder and violence. J Quant Crim 26:139–163

Zhu JF, Han XP, Wang BH (2010) Statistical property and model for the inter-event time of terrorism attacks. Chin Phys Lett 27:068902

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the Science and Technology Directorate of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security through the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), grant number N00140510629. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect views of the Department of Homeland Security. We would like to thank Joshua Freilich, Thomas Loughran, Erin Miller, Jacob Shapiro, David Weisburd, the editors of JQC, and the comments of two anonymous reviewers for their help in improving this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Behlendorf, B., LaFree, G. & Legault, R. Microcycles of Violence: Evidence from Terrorist Attacks by ETA and the FMLN. J Quant Criminol 28, 49–75 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9153-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9153-7