Abstract

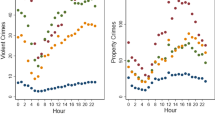

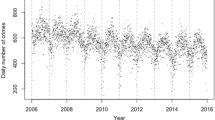

Seasonal crime patterns have been a topic of sustained criminological research for more than a century. Results in the area are often conflicting, however, and no firm consensus exists on many points. The current study uses a long time series and a large areal sample to obtain more detailed seasonality estimates than have been available in the past. The findings show that all major crime rates exhibit seasonal behavior, and that most follow similar cycles. The existence of seasonal patterns is not explainable by monthly temperature differences between areas, but seasonality and temperature variations do interact with each other. These findings imply that seasonal fluctuations have both environmental and social components, which can combine to create different patterns from one location to another.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Consistent with the bulk of research in all areas of the social sciences, we define seasonality as any cyclical pattern that repeats itself at regular intervals. The finer variation in monthly data allow a more detailed study of seasonal patterns than do quarterly aggregations into spring, summer, autumn, and winter. The relatively course quarterly aggregations may in fact obscure information about how seasonality occurs.

The temperature data are monthly means as recorded by the U.S. Weather Service. They were retrieved from http://www.eachtown.com on the World Wide Web, and were current as of June 5, 2011.

To streamline the presentation, all tables omit the eighty-seven city-specific fixed effects. Similarly to reduce clutter, the tables include only trend variables for time (grand mean centered) and its squared values. For some crimes, time polynomials up to the twelfth-order in fact significantly contributed to the models. This is unsurprising given the large sample size, and polynomials higher than the second-order did not substantively affect the other estimates.

Collinearity does not pose significant problems for the analysis. A single collinearity index for the entire set of eleven dummy variables is more helpful than are individual measures for each month. The study therefore evaluated collinearity using condition indices instead of the more familiar variance inflation factors. For the Table 1 models, the largest condition indices were twenty-two or less, below the value of thirty that Belsley et al. (1980) suggest as a threshold for concern. Much of the collinearity that did exist was due to the day-of-week measures. Dropping these from the analysis did not appreciably change the conclusions about seasonality, but it decreased the condition indices to eight or less.

These are Rogers robust standard errors, which allow for unspecified forms of within-city serial correlation. Newey-West robust standard errors resulted in inferences that were substantively similar but not absolutely identical. Both types of robust standard errors provide consistent estimates under very general assumptions about heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation structures. More detailed assumptions about the errors (as exist, for example, in an ARIMA model) would increase estimation efficiency if the assumptions were true. The large sample size makes efficiency a relatively unimportant consideration here, however. Peterson (2009) offers a thorough technical discussion of Rogers, Newey-West, and other robust standard errors for panel data. Stock and Watson (2007) consider the same material more intuitively and in a more general context.

Several of the contemporary studies that claim to find a winter property crime peak actually analyze robbery rates (e.g., Landau and Fridman 1993; Michael and Zumpe 1983). The FBI classifies robbery as a violent crime, and the purely property-related offenses of burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft all peak in August.

The analysis centered the monthly temperature variable about its grand mean to reduce collinearity with the other model components. Perhaps as a consequence, condition indices for the models including temperatures were only marginally higher than for their counterparts in Table 1.

In this connection, Kleck (1991) argues that assaults and homicides are less alike in their circumstances and motivations than criminologists often believe. He challenges especially the notion that weapon availability is often the only difference between the two crimes. Alternatively, Block (1984) argues that neither homicides nor assaults truly follow seasonal patterns. Instead, according to her explanation, assaults are more likely to come to police attention during the summer, so creating a false seasonality that depends on recording practices. Dodge (1988) found that aggravated assault reports by National Crime Survey respondents did have seasonal structure, however, and this is inconsistent with the operation of a recording artifact. More generally, the link between assaults and homicides has implications for many questions in criminology, and it deserves closer investigation than the current paper can give it.

The analysis used the centered monthly temperature variable to construct the interaction terms. The condition indices for the interaction models were all between 24 and 25. These are higher than for the other models, but still not large enough to suggest problematic collinearity levels.

A complication in evaluating the directional changes is that the coefficients in Table 3 use a mean-centered temperature variable for both the main and interaction effects. Many cities therefore have negative average temperatures in the early months of the year, and directional changes can occur even when the main and interaction effects have the same signs.

These models included city population as an exposure variable.

References

Anderson CA (1989) Temperature and aggression: ubiquitous effects of heat on occurrence of human violence. Psychol Bull 106:74–96

Anderson CA, Deuser WE, DeNeve K (1995) Hot temperatures, hostile affect, hostile cognition, and arousal: tests of a general model of affective aggression. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 21:434–448

Anderson CA, Bushman BJ, Groom RW (1997) Hot years and serious and deadly assault: empirical tests of the heat hypothesis. J Pers Soc Psychol 73:1213–1223

Baltagi BH (2008) Econometric analysis of panel data, fourth edn. Wiley, New York

Baumer E, Wright R (1996) Crime seasonality and serious scholarship: a comment on Farrell and Pease. Br J Criminol 36:579–581

Bell PA, Baron RA (1976) Aggression and heat: the mediating role of negative affect. J Appl Soc Psychol 6:18–30

Bell WR, Hillmer SC (1983) Modeling time series with calendar variation. J Am Stat Assoc 78:526–534

Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE (1980) Regression diagnostics: identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Wiley, New York

Berk R, MacDonald J (2009) The dynamics of crime regimes. Criminology 47:971–1008

Block CR (1984) Is crime seasonal? Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, Chicago

Brearley HC (1932) Homicide in the United States. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

Brockwell PJ, Davis RA (2002) Introduction to time series and forecasting, Second edn. Springer, New York

Ceccato V (2005) Homicide in São Paulo, Brazil: assessing spatial-temporal and weather variations. J Environ Psychol 25:307–321

Cohen J, Gorr W, Durso C (2003) Estimation of crime seasonality: a cross-sectional extension to time series classical decomposition. Working paper, H. John Heinz III School of Public Policy and Management, Carnegie Mellon University

Cohn EG (1990) Weather and crime. Br J Criminol 30:51–64

Cohn EG, Rotton J (1997) Assault as a function of time and temperature: a moderator- variable time-series analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol 72:1322–1334

Cohn EG, Rotton J (2000) Weather, seasonal trends and property crimes in Minneapolis, 1987–1988: a moderator-variable time series analysis of routine activities. J Environ Psychol 20:257–272

Cohn EM, Rotton J, Peterson AG, Tarr TD (2004) Temperature, city size, and southern subculture of violence: support for social escape/avoidance (sea) theory. J Appl Soc Psychol 34:1652–1674

DeFronzo J (1984) Climate and crime: tests of an FBI assumption. Environ Behav 16:185–210

Deutsch SJ (1978) Stochastic models of crime rates. Int J Compar Appl Crim Justice 2:128–151

Dodge RW (1988) The seasonality of crime victimization (NCJ-111033). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington

Dodge RW, Lentzner HR (1980) Crime and seasonality (NCJ-64818). U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington

Enders W (2010) Applied econometric time series, third edn. Wiley, New York

Farrell G, Pease K (1994) Crime seasonality:domestic disputes and residential burglary in Merseyside 1988–90. Br J Criminol 34:487–498

Field S (1992) The effect of temperature on crime. Br J Criminol 32:340–351

Ghysels E, Osborn DR (2001) The econometric analysis of seasonal time series. Cambridge University Press, New York

Gorr W, Olligschlaeger A, Thompson Y (2003) Short-term forecasting of crime. Int J Forecast 19:579–594

Hakko H (2000) Seasonal variation of suicides and homicides in Finland: with special attention to statistical techniques used in seasonality studies. Dissertation, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oulo. Downloaded 6-5-2011 from http://herkules.oulu.fi/isbn9514256042/html/

Harries KD, Stadler SJ (1983) Determinism revisited: assault and heat stress in Dallas, 1980. Environ Behav 15:235–256

Hipp JR, Bauer DJ, Curran PJ, Bollen KA (2004) Crimes of opportunity or crimes of emotion? testing two explanations of seasonal change in crime. Soc Forces 82:1333–1372

Hird C, Ruparel C (2007) Seasonality in recorded crime: preliminary findings. Home Office Online Report 02/07. Downloaded 6-5-2011 from http://www.compassunit.com/docs/rdsolr0207.pdf

Kleck G (1991) Point blank: guns and violence in America. Aldine De Gruyter, New York

Lab SP, Hirschel JD (1988) Climatological conditions and crime: the forecast is? Justice Q 5:281–299

Landau SF, Fridman D (1993) The seasonality of violent crime: the case of robbery and homicide in Israel. J Res Crime Delinquency 30:163–191

Maltz MD (1999) Bridging gaps in police crime data (NCJ 176365). U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington

Maltz MD (2007) Missing UCR data and divergence of the NCVS and UCR trends. In: Lynch JP, Addington LA (eds) Understanding crime statistics: revisiting the divergence of the NCVS and UCR. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 269–294

Maltz MD (2009) Monthly Uniform Crime Report (UCR) data from 1960 to 2004, for over 17,000 police departments, for 26 crime categories or subcategories [Computer data file]. Downloaded 6–5–2011 from http://sociology.osu.edu/mdm/UCR1960-2004.zip

McCleary R, Hay RA, with Meidinger EE, McDowall D (1980) Applied time series analysis for the social sciences. Sage, Beverly Hills

Michael RP, Zumpe D (1983) Annual rhythms in human violence and sexual aggression in the United States and the role of temperature. Soc Biol 30:263–277

Mills TC (2003) Modelling trends and cycles in economic time series. Palgrave, New York

Miron JA (1996) The economics of seasonal cycles. MIT Press, Cambridge

Peterson MA (2009) Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: comparing approaches. Rev Financ Stud 22:435–480

Quetelet A (1969/1842) A treatise on man and the development of his faculties. Scholars’ Facsimiles and Reprints, Gainesville

Rock D, Greenberg DM, Hallmayer J (2003) Cyclical changes of homicide rates: a reanalysis of Brearley’s 1932 data. J Interpersonal Violence 18:942–955

Rock D, Judd K, Hallmayer J (2008) The seasonal relationship between assault and homicide in England and Wales. Injury 39:1047–1053

Stock JH, Watson MW (2007) Introduction to econometrics, Second edn. Pearson-Addison Wesley, New York

Sutherland EH (1947) Principles of criminology, fourth edn. Lippincott, Phiadelphia

Tennenbaum AN, Fink EL (1994) Temporal regularities in homicide: cycles, seasons, and autoregression. J Quant Criminol 10:317–342

Time Use Institute (2010) How December is different. Downloaded 6-5-2011 from http://www.timeuseinstitute.org

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2010) American time use survey user’s guide. Downloaded 6-5-2011 from http://www.bls.gov/tus/atususersguide.pdf

Van Kopen PJ, Jansen RWJ (1999) The time to rob: variation in time of number of commercial robberies. J Res Crime Delinquency 36:7–29

Warren CW, Smith JC, Tyler CW (1983) Seasonal variation in suicide and homicide: a question of consistency. J Biosoc Sci 15:349–356

Wolfgang ME (1958) Patterns in criminal homicide. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

Yan YL (2004) Seasonality and property crime in Hong Kong. Br J Criminol 44:276–283

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDowall, D., Loftin, C. & Pate, M. Seasonal Cycles in Crime, and Their Variability. J Quant Criminol 28, 389–410 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9145-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9145-7