Abstract

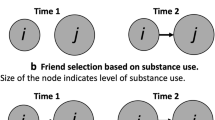

Much research on adolescent delinquency pivots on the notion of peer influence. The peer effect that is typically employed emphasizes the transmission of behaviors and attitudes between adolescents who are directly linked. In this paper, we argue that to rely solely on those direct social ties to capture peer influence oversimplifies the realities of adolescent society. We use data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health to show that indirect peer relations can exercise independent influences on adolescent delinquency. Adolescents actively draw on the examples of friends of friends, and even more distal peers, as they develop their repertoires of action and identity. We argue, however, that this behavior actually reflects adolescents’ ongoing struggle to impress their closest friends and to preserve their social circle. Indeed, the extent to which adolescents are willing to model the behavior of indirect contacts seems to decline as that behavior becomes more dissimilar from that of their close friends. Our findings dovetail with an account of the adolescent as a rational actor who struggles for social acceptance in a complex peer environment which offers conflicting behavioral models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Studies tend to: (1) employ a measure of differential association that captures adolescents’ perceptions of their friends’ delinquency rather than friends’ actual delinquency; (2) examine the effect of peer influence on substance use or cigarette smoking rather than more serious forms of delinquency; and (3) rely on samples for select places rather than ones that are nationally representative.

Urberg’s (1992) examination of adolescent substance use provides the only analysis of this sort to date. She finds that an adolescent’s best friend, rather than the larger social crowd, has the main influence on cigarette smoking. However, her study is based on data for a sample of adolescents from a single school system, and thus, may not be generalizable.

Because the emphasis here is on peer pressure, which is closely aligned with potential rewards and sanctions from friends, the conceptualization of social influence is closely related to Akers’ concepts of imitation and reinforcement. Adolescents are engaging in behavior resembling that of more distant peers because they are considering the consequence of that behavior—in this case, the consequence is approval or disapproval of close friends.

Initially, 160 schools were selected for the study, though some elected not to participate. Of the 132 schools comprising the main sample, two do not have sample weights, resulting in a usable sample of 130 schools. Among these, 112 had response rates sufficient for global network data. According to Moody (2001), this restricted sample is generally representative of all schools selected, and sample selection effects appear to be negligible.

The original responses are ordinal in nature, but to facilitate comparability with recent research, we use Haynie’s (2001) dichotomized version.

The wording of the questions about delinquency involvement, combined with the schedule of interviews for the Add Health study, means that T2 delinquency may have taken place prior to some of the predictors in the analysis. However, research on survey methodology (Blair and Burton, 1987; Burton and Blair 1991) suggests that respondents usually reference the more recent side of an expansive time frame when answering questions about the frequency of their own behavior. Thus, it is likely that the adolescents extrapolate from more recent behavior patterns to provide a picture of their behavior during the past year. In addition, there is a considerable period during which there is no overlap between the surveys. Nonetheless, future research should carefully consider the assumptions that go into using this measure.

While the correlation between risk-taking behaviors and more serious delinquency is far from perfect (r =0.47 in the saturation sample, which is a subset of schools wherein adolescents’ friends do answer questions about more serious delinquency), it is nonetheless statistically significant, which provides some support for using this measure with a larger, more representative sample. The saturation sample is limited to specific schools that were selected for their size (two very large schools and ten small schools) and comparisons between it and the core sample reveal that the saturation sample may under-represent adolescents from large schools (Haynie 2002). Moreover, as Haynie (2001) notes, using the risk-taking index may actually provide a more conservative estimate of peer effects on adolescent delinquency. Further, Osgood et al. (1988) offer evidence for the generality of deviance, which provides some justification for the use of this measure.

Instead of using merely the mean of friends’ behaviors, a diffusion approach might choose to model a decaying social distance function (where the effect of j’s behaviors on i’s delinquency is stronger when j is more proximate to i in the network). Myers (1997) models a similar decaying “contagion” effect of race riots in one U.S. city on the likelihood of race riots in another, measured as a function of increasing geographic distance between them. This is an amalgamated measure in that the effects of all the peers in one’s network, no matter how proximate, are considered together in one variable. This measure is attractive as an extension of the traditional peer effects variable, but it does not allow one to examine how the relationship between proximity and influence changes as proximity increases.

We consider these steps for two reasons: (1) some schools had few students, so the number of steps separating adolescents decreased as a function of school size (considering those with more distant ties would reduce the sample size and increase sample selection); and (2) it became clear early on that considering steps beyond three steps or more offered little additional information. More importantly, as a reviewer thoughtfully pointed out, adolescents probably do not define their peer relations in such detail as to justify numerous geodesic steps—four steps, five steps–away from them. We do want to highlight, however, that the number of direct ties in adolescents’ networks is very small compared to the number of indirect ties.

These values are calculated on the sent/received network using various SAS programming modules, available in SPAN (Moody 1999).

Bivariate correlations are available from the authors upon request. Examination of these correlations, as well as Variance Inflation Factor scores, revealed that the only high correlation in the model is between the interaction terms and their respective components.

Negative binomial regression expresses effects in terms of event rates, such that a one-unit increase in the independent variable leads to a percentage change in the rate of the dependent variable: =100[exp(β)−1] (Long 1997).

Despite such a small percentage of direct friendship ties, it is true that adolescents exert the most time and effort maintaining these close friendships; as Table 4 illustrates, the relatively small percentage of close versus distant ties does not belie their significance.

References

Akers RL (1998) Social learning and social structure: a general theory of crime and deviance. Northeastern University Press, Boston

Akers RL, Lee G (1996) A longitudinal test of social learning theory: adolescent smoking. J Drg Iss 26:317–343

Akers R, Krohn M, Lanza-Kaduce L, Radosevich M (1979) Social learning and deviant behavior: a specific test of a general theory. Am Soc Rev 44:636–655

Alarid LF, Burton VS Jr, Cullen FT (2000) Gender and crime among felony offenders: assessing the generality of social control and differential association theories. J Res Crime Del 37:171–199

Aseltine RH Jr (1995) A reconsideration of parental and peer influences on adolescent deviance. J Hlth Soc Beh 36:103–121

Bearman P, Brückner H (1999) Power in numbers: peer effects on adolescent girls’ sexual debut and pregnancy. The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, Washington, DC

Billy JO, Rodgers JL, Udry RJ (1984) Adolescent sexual behavior and friendship choice. Soc For 62:653–678

Blair E, Burton S. (1987) Cognitive processes used by survey respondents to answer behavior frequency questions. J Consumer Res 14:280–288

Burgess RL, Akers RL. (1966). A differential association-reinforcement theory of criminal behavior. Soc Prob 14:128–147

Burton S, Blair E (1991) Task conditions, response formulation processes, and response accuracy for behavioral frequency questions in surveys. Pub Opin Quar 55:50–79

Burt RS (2004) Structural holes and good ideas. Am J Soc 110:349–399

Burt RS (1992) Structural holes: the social structure of competition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Chantala K, Tabor J (1999) Strategies to perform a design-based analysis using the Add Health data. http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/strategies.html

Chilton R, Markle GE (1972) Family disruption, delinquent conduct, and the effect of subclassification. Am Soc Rev 37:93–99

Coleman JS (1990) Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Coleman JS (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Soc 4:95–120

Coleman JS (1961) The adolescent society: the social life of the teenager and its impact on education. The Free Press of America, Glencoe, NY

Cotterell J (1996) Social networks and social influences in adolescence. Routledge, London

Doreian P, Kapuscinski R, Krackhardt D, Szczypula J (1996) A brief history of balance through time. J Math Soc. 21:113–131

Eder D, Enke JL (1991) The structure of gossip: opportunities and constraints on collective expression among adolescents. Am Soc Rev. 56:494–508

Elliott DS, Voss H (1974) Delinquency and Dropout. DC Health, Lexington, MA

Erickson KG, Crosnoe R, Dornbush SM (2000) A social process model of adolescent deviance: combining social control and differential association perspectives. J Youth and Adol 29:395–425

Farrington DP (1986) Age and crime. In: Tonry M, Morris N (eds) Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research, vol 7. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Fine GA (1986). The social organization of adolescent gossip: the rhetoric of moral evaluation. In: Cook-Gumperz J, Corsaro W, Streeck J (eds) Children’s worlds and children’s language. Mouton, Berlin

Giordano PC (1995) The wider circle of friends in adolescence. Am J Soc 101:661–697

Giordano PC, Cernkovich SA, Groat HT, Pugh MD, Swinford S (1998) The quality of adolescent friendships: long term effects? J Hlth and Soc Beh 39:55–71

Granovetter MS (1973) The strength of weak ties. Am J Soc 78:1360–1380

Grattet R, Jenness V, Curry T (1998) The homogenization and differentiation of ‘hate crime’ law in the US, 1978–1995: an analysis of innovation and diffusion in the criminalization of bigotry. Am Soc Rev 63:286–307

Haynie D (2002) Friendship networks and delinquency: the relative nature of peer delinquency. J Quant Crim 18:99–134

Haynie D (2001) Delinquent peers revisited: does network structure matter? Am J Soc 106:1013–1057

Haynie D, Osgood WD (2005) Reconsidering peers and delinquency: how do peers matter? Soc For 84:1109–1130

Hirschi T (1969) Causes of delinquency. University of California Press, Berkeley

Jang SJ (1999) Age-varying effects of family, schools, and peers on delinquency: a multilevel modeling test of interactional theory. Crim 37:643–685

Jensen GF (1972) Parents, peers, and delinquent action: a test of the differential association perspective. Am J Soc 78:562–575

Jussim L, Osgood DW (1989) Influence and similarity among friends: An integrated model applied to incarcerated adolescents. Soc Psych Quart 52:98–112

Katz E, Levin M, Hamilton H (1963) Traditions of research in the diffusion of innovation. Am Soc Rev 28:237–252

Koopmans R (1993) The dynamics of protest waves: West Germany, 1965 to 1989. Am Soc Rev 58:637–658

Land KC, Deane G, Blau JR (1991) Religious pluralism and church membership: a spatial diffusion model. Am Soc Rev 56:237–249

Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M (1986) Family factors as correlates and predictors of juvenile conduct problems and delinquency. In: Tonry M, Morris N (eds) Crime and justice, vol 7. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 29–149

Long JS (1997) Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Marcos AC, Bahr SJ, Johnson RE (1986) Test of a bonding/association theory of adolescent drug use. Soc For 65:135–161

Matsueda RL (1982) Testing control theory and differential association: a causal modeling approach. Am Soc Rev. 47:489–504

Matsueda RL, Heimer K (1987) Race, family structure, and delinquency: a test of differential association and social control. Am Soc Rev 52:826–846

Mears DP, Ploeger M, Warr M (1998) Explaining the gender gap in delinquency: peer influence and moral evaluations of behavior. J Res Crime and Del 35:251–266

Minkoff DC. (1997) The sequencing of social movements. Am Soc Rev 62:779–799

Moody J (2002) The importance of relationship timing for diffusion: indirect connectivity and STD infection risk. Soc For 81:25–56

Moody J (2001) Race, school integration, and friendship segregation in America. Am J Soc 107:679–716

Moody J (1999) SPAN: SAS Programs for Analyzing Networks

Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ (1997) Violent crime and the spatial dynamics of neighborhood transition: Chicago, 1970–1990. Soc For 76:31–64

Morris M (1993) Epidemiology and social networks: modeling structured diffusion. Soc Meth and Res 22:99–126

Myers DJ (1997) Racial rioting in the 1960s: an event-history analysis of local conditions. Am Soc Rev 62:94–112

Osgood DW, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD (1988) The generality of deviance in late adolescence and early adulthood. Am Soc Rev 53:81–93

Osgood DW, Wilson JK, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD (1996) Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. Am Soc Rev 61:635–55

Pitcher BL, Hamblin RL, Miller JLL (1978) The diffusion of collective violence. Am Soc Rev 43:23–35

Ridgeway CL, Erickson KG (2000) Creating and spreading status beliefs. Am J Soc 106:579–615

Rogers EM (1995) Diffusion of innovations, 4th edn. The Free Press, New York

Soule SA, Zylan Y (1997) Runaway train? The diffusion of state-level reform in ADC/AFDC eligibility requirements. 1950–1967. Am J Soc 103:733–762

Sutherland EH (1947) Principles of criminology, 4th edn. JB Lippincott, Chicago

Tolnay SE, Deane G, Beck EM (1996) Vicarious violence: spatial effects of Southern lynchings, 1890–1919. Am J Soc 102:788–815

Urberg KA (1992) Locus of peer influence: social crowd and best friend. J Youth and Adol. 21:439–450

Valente T (1995) Network models of the diffusion of innovations. Hampton Press, New Jersey

Warr M (2002) Companions in crime: the social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Warr M (2001) The social origins of crime: Edwin Sutherland and the theory of differential association. In: Paternoser R, Bachman R (eds) Explaining criminals and crime: essays in contemporary criminological theory. Roxbury, Los Angeles

Warr M (1993) Age, peers, and delinquency. Crim 31:17–40

Warr M, Stafford M (1991) The influence of delinquent peers: What they think or what they do? Crim 29:851–866

Acknowledgments

We thankfully acknowledge the technical and editorial assistance of Ruth Peterson, Dana Haynie, and James Moody, as well as invaluable editorial suggestions for early drafts from Lauren Krivo, Lisa Keister, and Donna Bobbit-Zeher. We are also grateful to the editor and anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due Ronal R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Persons interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 W. Franklin Street, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524 (http://www.cps.unc.edu/addhealth/contract.html).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Payne, D.C., Cornwell, B. Reconsidering Peer Influences on Delinquency: Do Less Proximate Contacts Matter?. J Quant Criminol 23, 127–149 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-006-9022-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-006-9022-y