Abstract

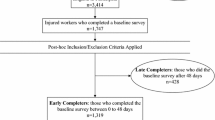

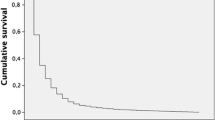

Objectives Some injured workers with work-related, compensated back pain experience a troubling course in return to work. A prediction tool was developed in an earlier study, using administrative data only. This study explored the added value of worker reported data in identifying those workers with back pain at higher risk of being on benefits for a longer period of time. Methods This was a cohort study of workers with compensated back pain in 2005 in Ontario. Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) data was used. As well, we examined the added value of patient-reported prognostic factors obtained from a prospective cohort study. Improvement of model fit was determined by comparing area under the curve (AUC) statistics. The outcome measure was time on benefits during a first workers’ compensation claim for back pain. Follow-up was 2 years. Results Among 1442 workers with WSIB data still on full benefits at 4 weeks, 113 were also part of the prospective cohort study. Model fit of an established rule in the smaller dataset of 113 workers was comparable to the fit previously established in the larger dataset. Adding worker rating of pain at baseline improved the rule substantially (AUC = 0.80, 95 % CI 0.68, 0.91 compared to benefit status at 180 days, AUC = 0.88, 95 % CI 0.74, 1.00 compared to benefits status at 360 days). Conclusion Although data routinely collected by workers’ compensation boards show some ability to predict prolonged time on benefits, adding information on experienced pain reported by the worker improves the predictive ability of the model from ‘fairly good’ to ‘good’. In this study, a combination of prognostic factors, reported by multiple stakeholders, including the worker, could identify those at high risk of extended duration on disability benefits and in potentially in need of additional support at the individual level.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Loisel P, Durand MJ, Berthelette D, Vezina N, Baril R, Gagnon D, et al. Disability prevention—new paradigm for the management of occupational back pain. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2001;9(7):351–60.

WSIB. 2012 Schedule 1 statistical report. 2013. Toronto, WSIB. 9-11-2013. Ref Type: Online Source.

Indahl A, Velund L, Reikeraas O. Good prognosis for low back pain when left untampered. A randomized clinical trial. Spine. 1995;20(4):473–7.

Hill JC, Whitehurst DG, Lewis M, Bryan S, Dunn KM, Foster NE, et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9802):1560–71.

Steenstra IA, Busse JW, Tolusso D, Davilmar A, Lee H, Furlan AD, et al. Predicting time on prolonged benefits for injured workers with acute back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(2):267–78.

Bultmann U, Franche RL, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Lee H, Severin C, et al. Health status, work limitations, and return-to-work trajectories in injured workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(7):1167–78.

Franche RL, Severin CN, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Vidmar M, Lee H. The impact of early workplace-based return-to-work strategies on work absence duration: a 6-month longitudinal study following an occupational musculoskeletal injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(9):960–74.

Steyerberg EW. Clinical prediction models. A practical approach to development, validation, and updating. New York: Springer; 2009.

McGinn TG, Guyatt GH, Wyer PC, Naylor CD, Stiell IG, Richardson WS. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXII: how to use articles about clinical decision rules. Evid Based Med Work Group JAMA. 2000;284(1):79–84.

Steenstra IA, Busse JW, Hogg-Johnson S. Predicting return to work for workers with low-back pain. In: Loisel P, Anema JR, Pransky GS, editors. Work disability prevention handbook. New York: Springer Science + Business Media New York; 2013.

Du Bois M, Szpalski M, Donceel P. Patients at risk for long-term sick leave because of low back pain. Spine J. 2009;9(5):350–9.

Turner JA, Franklin G, Fulton-Kehoe D, Sheppard L, Stover B, Wu R, et al. ISSLS prize winner: early predictors of chronic work disability: a prospective, population-based study of workers with back injuries. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(25):2809–18.

Cifuentes M, Webster B, Genevay S, Pransky G. The course of opioid prescribing for a new episode of disabling low back pain: opioid features and dose escalation. Pain. 2010;151(1):22–9.

Franklin GM, Stover BD, Turner JA, Fulton-Kehoe D, Wickizer TM. Early opioid prescription and subsequent disability among workers with back injuries: the Disability Risk Identification Study Cohort. Spine. 2008;33(2):199–204.

Pransky GS, Verma SK, Okurowski L, Webster B. Length of disability prognosis in acute occupational low back pain: development and testing of a practical approach. Spine. 2006;31(6):690–7.

Schultz IZ, Crook J, Meloche GR, Berkowitz J, Milner R, Zuberbier OA, et al. Psychosocial factors predictive of occupational low back disability: towards development of a return-to-work model. Pain. 2004;107(1–2):77–85.

Johnson WG, Butler RJ, Baldwin ML. First spells of work absences among Ontario workers. In: Thomason T, Chaykowski RP, editors. Research in Canadian workers’ compensation. Kingston: IRC Press; 2005.

Steenstra IA, Verbeek JH, Heymans MW, Bongers PM. Prognostic factors for duration of sick leave in patients sick listed with acute low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(12):851–60.

Pransky G, Shaw W, Franche RL, Clarke A. Disability prevention and communication among workers, physicians, employers, and insurers–current models and opportunities for improvement. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26(11):625–34.

Franche RL, Cullen K, Clarke J, Irvin E, Sinclair S, Frank J. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15:607–31.

Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50(2):133–49.

Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine. 1983;8(2):141–4.

Karasek R. Job Content Instrument Users Guide: revision 1.1. Los Angeles: University of Southern California; 1985.

Franche RL, Carnide N, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Breslin FC, Bultmann U, et al. Course, diagnosis, and treatment of depressive symptomatology in workers following a workplace injury: a prospective cohort study. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(8):534–46.

Croft PR, Dunn KM, Raspe H. Course and prognosis of back pain in primary care: the epidemiological perspective. Pain. 2006;122(1–2):1–3.

Steenstra IA, Lee H, de Vroome EM, Busse JW, Hogg-Johnson SJ. Comparing current definitions of return to work: a measurement approach. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(3):394–400.

Radloff LS. The CES_D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401.

Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers PM, Amick B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(4):322–55.

Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. London: Chapman & Hall; 1994.

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36.

Murray E, Franche RL, Ibrahim S, Smith P, Carnide N, Cote P, et al. Pain-related work interference is a key factor in a worker/workplace model of work absence duration due to musculoskeletal conditions in Canadian nurses. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(4):585–96.

Franche RL, Murray E, Ibrahim S, Smith P, Carnide N, Cote P, et al. Examining the impact of worker and workplace factors on prolonged work absences among Canadian nurses. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(8):919–27.

Shaw WS, Linton SJ, Pransky G. Reducing sickness absence from work due to low back pain: How well do intervention strategies match modifiable risk factors? J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(4):591–605.

Heymans MW, van BS, Knol DL, Anema JR, van MW, de Vet HC. The prognosis of chronic low back pain is determined by changes in pain and disability in the initial period. Spine J. 2010;10(10):847–56.

Heymans MW, Ford JJ, McMeeken JM, Chan A, de Vet HC, van MW. Exploring the contribution of patient-reported and clinician based variables for the prediction of low back work status. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(3):383–97.

Heymans MW, Anema JR, van BS, Knol DL, van MW, de Vet HC. Return to work in a cohort of low back pain patients: development and validation of a clinical prediction rule. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(2):155–65.

Kirkwood R. External validation of the orebro musculoskeletal pain screening questionnaire within an injured worker population: a Retrospective Cohort Study Open Access Dissertations and Theses. 2011. https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/handle/11375/11432

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steenstra, I.A., Franche, RL., Furlan, A.D. et al. The Added Value of Collecting Information on Pain Experience When Predicting Time on Benefits for Injured Workers with Back Pain. J Occup Rehabil 26, 117–124 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-015-9592-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-015-9592-3